OGIS Issue Assessment: Agency FOIA Websites

Note: We are conveying these findings and recommendations to the Office of Information Policy (OIP) as per FOIA Advisory Committee Recommendation No. 2020-01 that recommends OIP issue further "guidance on how agencies may improve online descriptions of the [FOIA] process." It is important to acknowledge that the review of each agency FOIA website reflects a snapshot in time, and FOIA programs may have updated their websites since the review.

Published November 28, 2022

| What OGIS Found | What OGIS Recommends |

|

Finding 1: Almost all agency FOIA websites OGIS visited have deficiencies in the information they include. (Recommendation 1) Finding 2: There are some data points that almost all agencies include; however, a slim minority of agency websites have deficiencies. (Recommendation 1) Finding 3: Agencies generally include ample information on their websites but finding it can often be difficult. (Recommendation 2) |

Recommendation 1: Agencies should address the deficiencies in the information they include about FOIA. Recommendation 2: Agencies should make finding information on websites easier. |

| What OGIS Reviewed | |

| From January 2021 to April 2021, the Office of Government Information Services (OGIS) reviewed FOIA websites for all 15 Cabinet-level departments, including their components, and six independent agencies. For each site, OGIS reviewed the presence or absence of 25 criteria that reflect OIP guidance and FOIA Advisory Committee best practices for FOIA websites. | |

Executive Summary

On July 9, 2020, the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Advisory Committee recommended that the Office of Government Information Services (OGIS) at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) assess agency FOIA websites to determine the clarity and availability of information about filing a FOIA request. (Recommendation 2020-01) The Committee recommended this assessment with the express intent that it inform further guidance from the Department of Justice’s (DOJ) Office of Information Policy (OIP).

Recommendation 2020-01 seeks to help create a more efficient FOIA process through improved websites that educate FOIA requesters, improve the quality of requests, and answer frequently asked questions, thereby reducing the burden on both agencies and requesters. FOIA websites can significantly further the goal of transparency in government; however, to fully leverage the potential effectiveness, agencies must create content and layout for their websites geared toward FOIA requesters, especially novice requesters.

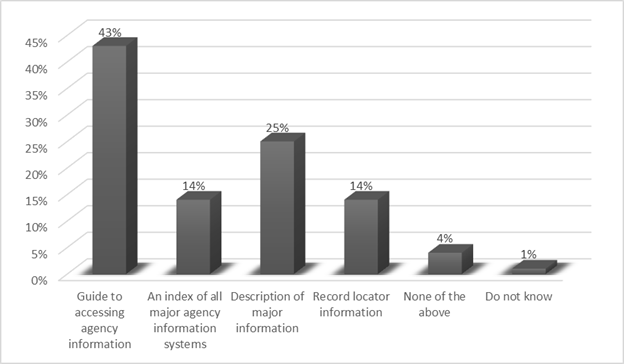

OGIS’s foundational work in complying with the Committee’s recommendation was its report Assessing FOIA Compliance through the 2019 NARA Records Management Self-Assessment, published in March 2021.The assessment leveraged NARA's annual Records Management Self-Assessment (RMSA) to ask what types of information agencies include on their FOIA websites about requesting records.

OGIS built on the data from the RMSA by reviewing information on FOIA websites. OGIS found that FOIA websites across the government have significant room for improvement in two areas: complete instructions for—and comprehensive information about—filing a FOIA request; and layout and ease-of-navigation. We recommend that agencies should address the deficiencies in the information they include, and that agencies should make finding information on websites easier.

Finally, many of the deficiencies could be remedied by implementing recommendations made by the 2020-2022 term of the FOIA Advisory Committee. Specifically, in Recommendation 2022-07, the Committee lists 16 elements that agencies should include on their FOIA websites, including links to descriptions of the records maintained by the agency and those that do not exist at the agency; agency records schedules; a FOIA request submission form; and contact information for agency FOIA personnel.

Background

On July 9, 2020, the FOIA Advisory Committee submitted 22 recommendations for government-wide improvements for the implementation of FOIA to the Archivist of the United States [1]. Recommendation 2020-01 was among several intended to enhance online access and applied to NARA, OGIS, OIP, as well as other federal agencies.

We recommend that [OGIS] undertake an assessment of the information agencies make publicly available on their FOIA websites to facilitate the FOIA filing process and for the purpose of informing further guidance by [OIP] on how agencies may improve online descriptions of the process.

This recommendation comports with the two offices' respective roles. OGIS, as the federal FOIA Ombudsman, reviews FOIA policies, procedures, and compliance, and identifies procedures and methods for improving FOIA compliance. OIP, as part of its responsibilities to encourage agency compliance with FOIA, provides FOIA guidance to federal agencies, including 10 basic recommendations for agency websites.[2] The Attorney General issued updated FOIA guidelines via a Memorandum for Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies in March 2022 stressing the “importance of improving the organization and presentation of disclosed materials [as] a core part of our efforts to efficiently provide government records to the public.” [3] The Memorandum also noted that “FOIA websites should be easily navigable, and records should be presented in the most useful, searchable, and open formats possible.”

The FOIA Advisory Committee made its recommendation in 2020 regarding FOIA websites to foster efficiencies in the FOIA process, commenting in its final report:

The number of FOIA requests filed annually across all agencies has generally increased every year during the past decade ... with only a slight drop … in FY 2019. Requests are expected to continue to increase [and] agency resources have largely remained stagnant during that time.… The FOIA Advisory Committee’s Time/Volume Subcommittee conducted voluntary surveys of FOIA officers and requesters [finding that] more than half of all FOIA officers who responded said that agency capacity to handle FOIA requests is the single greatest impediment within the agency’s control to processing FOIA requests on time. [The] FOIA requester community indicated a willingness by requesters to modify their requests if given better tools to do so … e.g., clear instructions on how the public can simplify their requests (emphasis added).[4]

Indeed, OGIS has observed that an effective website serves to educate FOIA requesters, improves the quality of requests, and preempts questions, thereby reducing the administrative burden on the agency. It is in the best interest of agency FOIA offices to focus resources on website design and layout to efficiently leverage their limited funding. Despite the efficiencies that well-designed websites could bring, the FOIA Advisory Committee found in its recommendations to the Archivist that “in many instances FOIA information on agency websites remains incomplete, inconsistent, and out of date.”[5]

OGIS’s Assessing FOIA Compliance through the 2019 NARA Records Management Self-Assessment (conducted in 2020 and published after a pandemic delay in March 2021) follows the Committee's recommendation to assess information on FOIA websites. Specifically, it reported on a question federal agencies were asked as part of the RMSA for calendar year 2019:[6]

Q27. Which of the following does your agency/component have available on its FOIA website for requesting records? (Choose all that apply)

Building on these results, OGIS reviewed information on 158 FOIA websites, as described below. This report is the product of that research.

Methodology

In conjunction with the comments that the 2018-2020 term of the FOIA Advisory Committee provided on Recommendation 2020-01, OGIS used the responses to the 2019 RMSA Q27 as a baseline to identify measurement criteria for agency FOIA websites. There were 25 data points against which OGIS measured each website. OGIS developed the data points (see Appendix A for complete list) from the FOIA statute, OIP guidance, and FOIA Advisory Committee best practices for publishing on websites information to facilitate FOIA requesting.

OGIS reviewed the websites for all 15 Cabinet-level departments, their component agencies,[7] and six independent agencies that together received 93 percent of FOIA requests governmentwide in FY19, the most recent data available at the time of the review.[8] (In FY21, those agencies received 97 percent of FOIA requests governmentwide.)

OGIS reviewed the websites between January 2021 and April 2021. As OGIS reviewed each website, the presence or absence of each criterion was noted. This data demonstrated the extent to which agencies follow OIP guidance and FOIA Advisory Committee best practices for publishing particular information on their websites. At a minimum, FOIA websites should include contact information, FOIA request instructions, definitions of key terms, and a FOIA library.

OGIS reviewed each agency FOIA website to determine the presence or absence of 25 data points, pertaining to various aspects of the FOIA administrative process and records management, as well as contact information for agency FOIA personnel.

Note: It is important to acknowledge that the review of each agency FOIA website reflects a snapshot in time, and FOIA programs may have updated their websites since the review. For the websites mentioned in the next section (Department of Treasury's Internal Revenue Service (IRS), Department of State, and Department of Defense's (DoD) Education Agency), OGIS conducted a follow-up review in July 2022. The websites continue to demonstrate the strengths mentioned below.

Findings

Three overall themes emerged while evaluating the websites.

- First, under the criteria used for the analysis, almost all agency FOIA websites had some deficiencies in the information they included.

- There are some data points that almost all agencies include; however a slim minority of agency websites have deficiencies.

- While most agencies included ample information on their websites, finding specific information was often difficult. It appeared that some FOIA websites are designed for savvy rather than novice FOIA requesters, and information was not arranged to make it easily accessible to the general public who may not have any experience with the FOIA process.

Finding 1: Almost all agency FOIA websites OGIS reviewed had deficiencies in the information they include.

At the time of our review, no agency website contained a completely comprehensive and up-to-date list of everything needed to file a FOIA request. On almost every website, information needed to be added or updated to give novice FOIA requesters a step-by-step guide on requirements for filing. For example, the U.S. Department of Treasury’s Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) webpage could be improved if it explained the role of the FOIA Public Liaison (FPL) on its site instead of linking to the “Freedom of Information Act, 5 U.S.C. Sec. 552.” A description on the agency’s FOIA website would help users understand the role of the FPL without referring them to the statutory language.

Some websites included a majority of the criteria that OGIS measured. For example, the FOIA website for the Department of the Treasury’s Internal Revenue Service (IRS) met nearly all of the 25 criteria. It lacked only two criteria: a definition of “simple and complex” requests (column V) and the average processing times broken down by simple and complex requests (column W). Based on our review, a website that met nearly all criteria was the exception.

Even websites that provided most of the expected information still have room for improvement. The Department of State’s FOIA website, like the IRS’s, contains most of the information a user would need. However, it did not include a date when the electronic reading room was last updated (column H), nor did it provide average processing times, including for simple and complex requests (column W). In addition, a couple of the expected pieces of information were present but not clear for people unfamiliar with FOIA. These included unclear definitions for “simple” and “complex” requests (column V), and a lack of description of the types of requests that the agency would consider overly burdensome or not sufficiently specific (column Y).

In certain cases, an agency FOIA website excelled in one category, but fell short in others. For example, the Department of Defense (DoD) Education Agency’s FOIA website interface was easy to navigate. It had a prominent horizontal menu bar with tabs “How to File a FOIA Request?,” “How to File a FOIA Appeal?,” “FOIA Library,” “Letter Templates & Forms,” “Handbook & Regulations,” and “How to File a Privacy Act (PA) Request?” This is a best practice in website design because viewers do not have to scroll down to view important navigation elements. Most users find it easier to read horizontal lines rather than vertical lines of text, and a horizontal menu bar generally makes the website easier to navigate. On the other hand, the DoD’s Education Agency website did not explain what the FOIA is in a high-level introductory paragraph. Rather, it began by presenting specific information with no context for the user.

Additionally, there were some criteria for which most agency websites did not include specific FOIA information. For example, many websites did not:

- directly link to a FOIA request submission form (Column K)

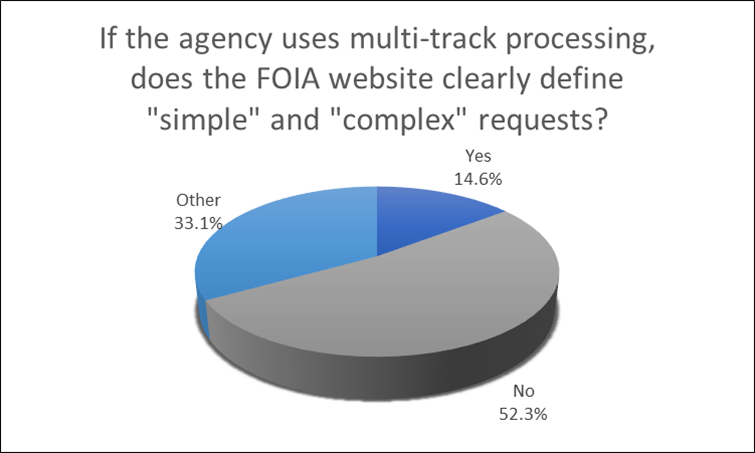

- clearly define “simple” and “complex” requests (Column V)

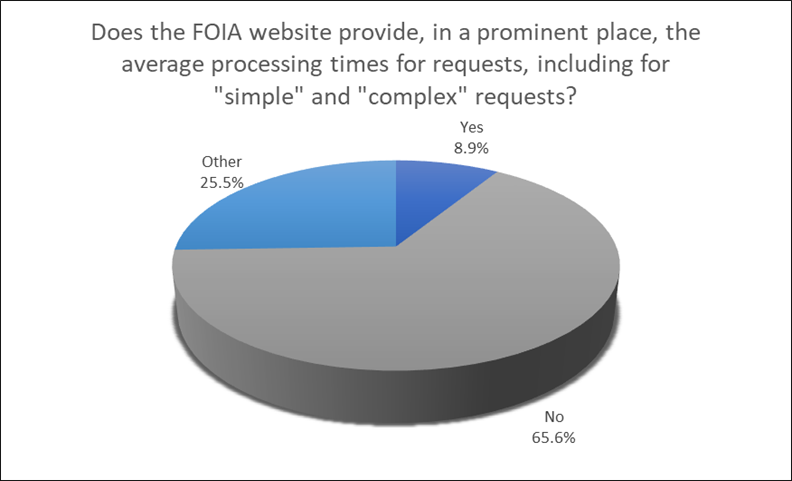

- provide average processing times (Column W)

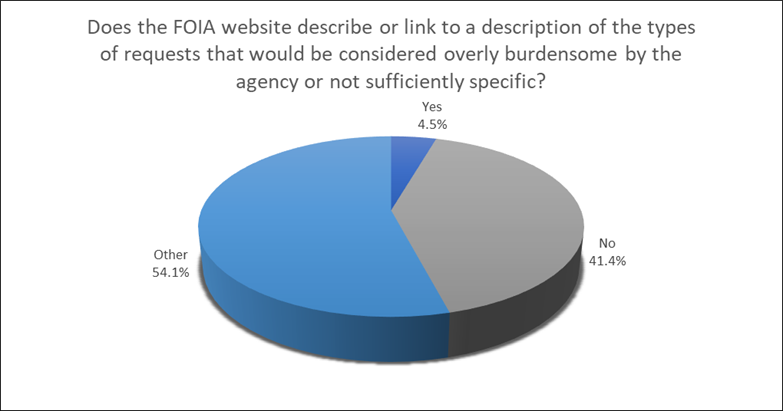

- describe or link to a description of the types of requests that would be considered overly burdensome by the agency or not sufficiently specific (Column Y)

- post agency FOIA logs to its FOIA website and/or FOIA Library/Reading Room (Column AC)

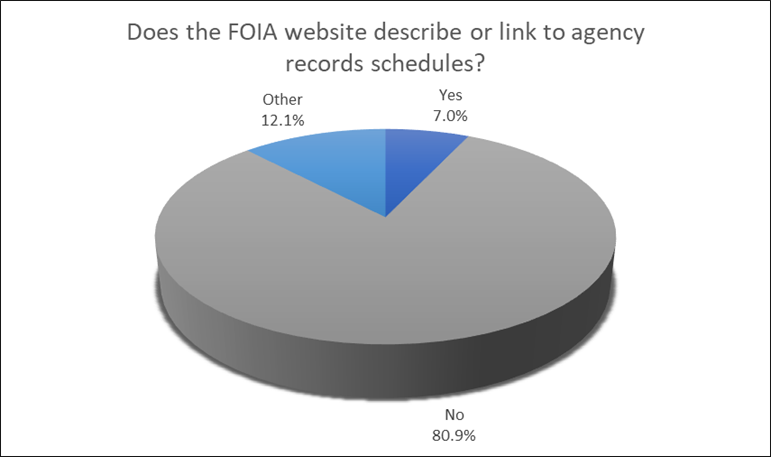

- describe or link to agency records schedules (Column AE)

Directly link to a FOIA request submission form

Almost half of the websites (45.2 percent) do not link to a form, while more than the 43.3 percent of websites do link to such a form. Eighteen websites (11.5 percent) fell into the “other” category. The most common reason for the “other” category was that the website link refers the user to foia.gov, and to a lesser extent, foiaonline.gov,[9] which have online forms. Very rarely are there direct links to agency-created forms. In some cases, a requester needs to download the form, fill it out, and either email or print and mail it. In one instance, the form was inconspicuously buried in the footer. On another website, the form was found in the electronic reading room instead of in an intuitive place. A few of the websites had broken links to the form or the user was directed to an error page.

Clearly define 'simple' and 'complex' requests

There are a few reasons for a website to be categorized as “other.” Sometimes clear definitions of simple and complex requests are technically included but functionally hidden: for example, found within annual reports stored in an electronic reading room or in an agency’s FOIA regulations. It is especially unhelpful when the website does not even direct users to these definitions. In other instances, one term is defined but not the other.

Some agencies, instead of using the terms “simple” and “complex,” use alternate terminology. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), for example, uses the terms “small,” “medium,” “large” and “extra large” for its processing tracks based on the number of pages responsive to the request.[10] The FBI FOIA website explains that it uses page count thresholds to route requests into each track, that requests encompassing a high volume of responsive records will take a longer time to process, and that for “large” and “extra large” requests the FBI will contact the requester in an effort to narrow the request in order to potentially reduce fees and processing time.

On other agency FOIA websites, a definition is implied without clearly spelling out the terms.

Provide average processing times

Few websites provide average processing times (including for “simple” and “complex” requests) in a prominent place. Sometimes an FAQ section will have the information under a “how long will it take to process my request?” type of heading.

Describe or link to a description of the types of requests that would be considered overly burdensome or not sufficiently specific

Websites often were categorized under “Other” because they included a link to the U.S. Department of Justice Guide to the FOIA and indicated that users could look there for descriptions of 'overly burdensome' or 'not sufficiently specific.'

Also falling into “Other” was one instance in which the navigation to a system to look up logs required explanation. In other cases, an “access denied” page came up or the link was broken. Sometimes there was no reading room.

Description of Agency Records Schedules

In the case of “Other,” sometimes the navigation needed clarification. Other times there were no direct links, requiring the user to search for a Records Management Page to find the information. This is not helpful for casual users who do not have the context to know to search for this information. Other issues found in OGIS’s review range from information included only within the language of a directive to broken links to information on external websites.

Finding 2: There are some data points that almost all agencies include; however a slim minority of agency websites have deficiencies.

Certain types of FOIA information are overwhelmingly present across all agency FOIA websites. For those criteria, only a slim minority of agency websites have deficiencies. As the data below indicate, a vast majority of agencies:

- provide instructions on how to file a FOIA request

- host electronic reading rooms

- make contact information available for FOIA Office(s)

- include accessibility statements

How to make a FOIA Request

The vast majority of websites (92.4 percent) include instructions to the public on how to make a FOIA request. Usually, instructions take the form of a dedicated link, some paragraphs, or a handbook. Ten websites (6.4 percent) are classified as “other.” The most common reason is minimal instructions, such as not providing contact information for submission of requests. Other times the navigation to instructions is indirect (taking multiple clicks), usually to a parent department’s FOIA handbook. Many FOIA websites rely heavily on general FOIA resources (see www.foia.gov). In a few instances, the link to instructions is broken.

FOIA Reading Room

Over 85 percent of agency FOIA websites have an online FOIA library. Often, the electronic reading room goes by another name, such as “FOIA Reading Room,” “E-Library,” “Frequently-Requested Documents,” etc. For the 12.1 percent of websites that were categorized as “other,” the most common reason was that there was no dedicated reading room page, but the websites included many of the types of records one would find in a reading room (such as annual reports). A small number of websites, 2.5 percent of the total, either had a missing link, a broken link, or an “access denied” error.

Contact Information

Of the 158 agency FOIA websites OGIS reviewed, 97.5 percent included contact information for the FOIA office. Only 2.5 percent failed to provide contact information for the FOIA office. Contact information included names, emails, physical addresses, telephone numbers, and/or fax numbers.

Accessibility Statement

Most agency FOIA websites included an accessibility statement or Section 508 page that individuals with disabilities can use if they encounter inaccessible documents. OGIS found that 7.6 percent of sites included the statement at the top of the page, while 86.6 percent placed the link in the website footer. Only 5.7 percent of websites did not have an accessibility statement.

Other Exemplary Practices

Certain agency FOIA websites were notable in other ways. The website for the Administration for Children and Families at the Department of Health and Human Services not only described records that are available through FOIA, but also which records are not.[11] This additional context potentially reduces unnecessary requests contributing to backlogs. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Rural Development Agency included a prominent link on its website to a Certificate of Identity form (DOJ Form 361), with a thorough explanation of why the form is necessary for requests that seek records containing information about oneself in order to release that information to third parties.

Finding 3: Agencies generally include ample information on their websites but finding it can be difficult.

OGIS’s analysis demonstrated that often the issue is not whether information is on a website, but rather the difficulty of locating and interpreting the information. Often information was located only by navigating through multiple clicks, searching through agency FOIA regulations, navigating external link FAQs, or delving into FOIA handbooks.

FOIA sites tend to have a deep hierarchy, requiring users to navigate through several intermediary landing pages. A more user-friendly approach would be to organize the site collection from a user’s point of view and use a flat structure to direct users from the central homepage to the content pages (e.g., a flowchart model). Agencies tend to bury information under several layers of nested pages, which frequently make it difficult for a general user to find information.

When agency websites require users to navigate through complex site collections to learn about FOIA instead of directly linking to specific information, they obscure potentially important information with additional layers of navigation. It puts an additional burden on requesters to find the information, even if they know it likely exists somewhere on a website and is worth locating.

For example, the Department of State’s FOIA website does not describe or link to a description of the types of requests that would be considered overly burdensome by the agency or not sufficiently specific (column Y). Instead, a FOIA requester must click “Learn,” then “Freedom of Information Act,” then “Other Resources,” then “DOJ Guide to the Freedom of Information Act,” and then select a left-hand menu link “DOJ Guide to the FOIA.” Once there, they would have to view the section “Searching for Responsive Records,” which discusses some examples of burdensome requests.

When OGIS found that an agency was not fully successful in clearly explaining a key phrase or making information easy to find, the agency earned a response of “Other” for that data point. In those cases, OGIS noted why the finding did not fit into the “Yes” or “No” response category.

For some agencies, many data points required explanations. For example, below are the notes from OGIS’s findings for the Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics’ FOIA website. The bolded letters refer to individual columns, followed by comments explaining answers in detail. For example, Column W, which asks “Does the FOIA website provide, in a prominent place, the average processing times for requests, including for simple and complex requests?” demonstrated how nuanced answers could be:.

- G: While there is no clearly defined Reading Room, many of the documents found in similar rooms like “FOIA Request Lists” [FOIA Logs] and “Annual FOIA Reports” are found in the sections “Frequently Requested Materials” and “Other FOIA Resources.”

- I: No, although they encourage users to review available records on bls.gov before making a request.

- L-N: Not directly. The web site links to the “DOL Guide for Requesting FOIA Records,” which discusses expedited processing under “VII. Can My FOIA Request Be Processed Faster?” Fees are discussed under “VIII. Are There Any Fees?” Waivers are explained under “IX. Can I Request a Fee Waiver?”

- P: Not directly. The page links to the DOJ FOIA page under “Other FOIA Resources.” Once there, click the dropdown left hand sidebar menu for “Make a FOIA Request to DOJ” and select “DOJ Reference Guide.” Under “IV. How to Make a FOIA Request” it states “Similarly, if you request records relating to another person, and disclosure of the records could invade that person’s privacy, they ordinarily will not be disclosed to you.”

- Q: Yes, although they use the DOL FOIA Regulations.

- S: No, although they do have contact information for a BLS FOIA Coordinator.

- T: No, although the previously mentioned DOJ FOIA Guide does explain the role of the FOIA Liaison.

- U: Yes, but not directly. Under the left-hand menu column of the DOJ Reference Guide, click “DOJ Guide to FOIA,” which has a section with a definition for an agency record.

- W: Sort of. The “DOL Guide for Requesting FOIA Records” section “VI. How Long Will It Take to Answer My FOIA Request?” gives time frame extensions for requests under certain circumstances that would be considered “complex,” but does not give definitions for “simple” and “complex” as such.

- Y: Not directly. Within the previously mentioned U.S. Department of Justice Reference Guide is a left-hand menu link to “DOJ Guide to the FOIA.” Within it is a section “Searching for Responsive Records,” which discusses some examples of burdensome requests.

- AB: Yes. At the bottom of the page under “About This Site” is a link “Important Website Notices,” which links to an Accessibility statement.

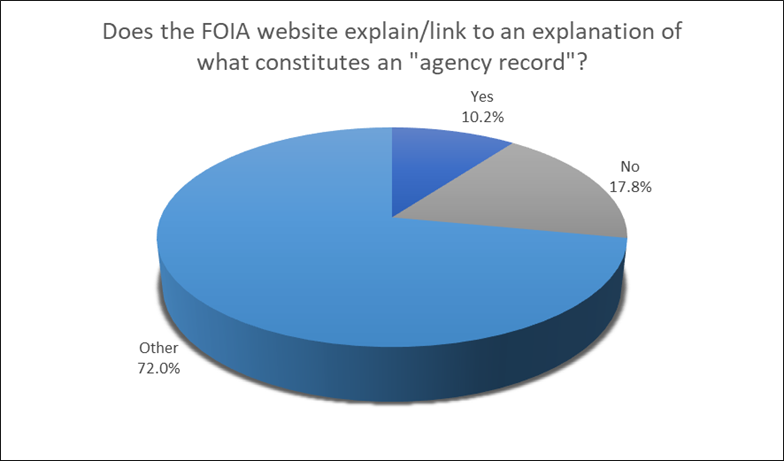

There were also certain criteria that many agencies were not fully successful in meeting. As shown below, 72 percent of agency websites did not have a clear “yes/no” answer for clearly defining a record (column U). In order for an agency to earn a clear “yes” the definition of a record should be readily available on the website where novice FOIA requesters are likely to encounter it for the first time.

Definition of Agency Records

As noted above, agencies generally were categorized as “other” because the information was technically present but hard to find, requiring effort to locate. For example, on many DoD websites, there is no direct link to a definition of an agency record. Instead, the information is found by following links to the DoD FOIA Handbook FAQ section “What is a Record?” For some agency FOIA websites, the definition of an agency record is buried within agency FOIA regulations. Many other websites link to the “DOJ Guide to the FOIA.” The DOJ FOIA Guide is a comprehensive legal treatise on FOIA, so the content is likely to appear dense and too legalistic for a requester who merely needs to know what an agency record is.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: Agencies should address the deficiencies in the information they include.

Agencies should review OIP’s best practices and the OGIS evaluation criteria (see Appendix A) to ensure their websites contain the information a FOIA requester would need to file a request. Ideally, an agency website should contain and host all the information novice requesters would need to educate themselves on the filing and appeal processes.

Furthermore, agencies should commit to reviewing their websites regularly for outdated information. In its review, OGIS found widespread outdated information ranging from broken links, links that direct to the incorrect page, outdated copies of the Code of Federal Regulations, outdated statements about the time frame for submitting an appeal (90 days under the FOIA Improvement Act of 2016), the latest FOIA logs in electronic reading rooms, and the most recent dates pages were modified.

Recommendation 2: Agencies should redesign their websites in order to make finding information easier

Agencies should continue to work towards a design that includes an appropriate amount of information on the FOIA home page, presented clearly and logically, with a flat navigational structure that maximizes a user’s ability to find information quickly. In addition to working with their agency’s web team, FOIA professionals can refer to the Federal Web Council for best practices on website design. A further implementation of best practices in design will help casual users to educate themselves about the FOIA process and may reduce the need for government FOIA professionals to work with requesters to perfect their requests.

It is also critical that all agencies provide prominent, concise descriptions of their mission and program activities, and the records created and maintained as a result. This would provide requesters critical information regarding the types of records they could request in addition to the ones already available in electronic reading rooms. When accompanied with links to agency records schedules and instructions on how to use them, the public could identify more specific records to request under FOIA.

Conclusion

Over the past 30 years, the internet has revolutionized the interaction between the public and the government with agencies able to disseminate information and procedures more efficiently than ever before. As part of this evolution, federal agencies’ use of the internet to educate and interact with the public about the FOIA process has allowed the public to increasingly exercise its right to access federal records under the FOIA. FOIA websites can significantly further the goal of transparency in government. However, to fully leverage the effectiveness of the internet, agencies must invest further planning and attention to the design of their websites and make conscious editorial and design decisions with the FOIA user in mind. The evaluation criteria from this report can serve as a roadmap for website designers.

Many of the deficiencies noted in this assessment could be remedied by implementing recommendations made by the 2020-2022 term of the FOIA Advisory Committee. Specifically, in Recommendation 2022-07, the Committee lists 16 elements that agencies should include on their FOIA websites. Those include a link to a description of the records maintained by the agency as well as a description of records that do not exist at the agency; a link to agency records schedules; a FOIA request submission form; average processing times for requests, including for “simple” and “complex” requests; and descriptions of the types of requests that would likely be considered unduly burdensome and/or not reasonably described.

Gregory Tavormina, an Archivist with the National Archives’ Accessioning, Basic Processing & Holdings Security Branch, conducted this review on temporary assignment to OGIS as part of a National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) Cross-training Program. (He is now an Archivist with NARA’s Special Access and FOIA Program).

Footnotes

1. Freedom of Information Act Federal Advisory Committee, 2018-2020 Committee Term Final Report and Recommendations, https://www.archives.gov/files/ogis/assets/foiaac-final-report-and-recs-2020-07-09.pdf and included in the appendix of this report.

2. See https://www.justice.gov/oip/foia-resources/foia-self-assessment-toolkit/download, pp. 64-68.

3. See Part C Paragraph 2, “U.S. Attorney General Memo to Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies RE: Freedom of Information Act Guidelines,” https://www.justice.gov/ag/page/file/1483516/download

4. See page 9 “Freedom of Information Act Federal Advisory Committee, 2018-2020 Committee Term Final Report and Recommendations” https://www.archives.gov/files/ogis/assets/foiaac-final-report-and-recs-2020-07-09.pdf.

5. Id.

6. NARA administered the RMSA for calendar year 2019 to agency records officers from January 13, 2020, to May 15, 2020.

7. See Appendix B for complete list

8. In FY19, the six independent agencies with the most FOIA requests received between 8,869 and 67,466 requests. In contrast, the agency with the seventh highest number received 2,972 requests.

9. The FOIAonline.gov service will be retired by the end of December 2023. Each agency that currently uses FOIAonline is responsible for finding a replacement.

10. Subsequent to our initial review, the FBI created an “extra large” track for requests with 5,000 or more responsive pages.

11. See What information is not available under the FOIA? and FOIA Exemptions & Exclusions.

PDF files require the free Adobe Reader.

More information on Adobe Acrobat PDF files is available on our Accessibility page.