Glass Holdings in the Still Picture Branch

Introduction

Different photographic formats present different preservation challenges; perhaps none more so than glass holdings. The Still Picture Branch has never calculated an exact count of its glass holdings, which include glass plate negatives, lantern slides, and a small number of ambrotypes, but the current estimate is over 500,000 items. This includes black-and-white and hand-colored images dating from the late 1850s through the 1950s.

When compared to film, the photographic support that largely supplanted glass as the 20th century progressed, glass is more dimensionally stable; it is not going to bend, curl, shrink, or tear. This is especially true for larger dimensions. One series maintained by the Still Picture Branch, Photographs Relating to Astronomical Surveys, 1969-2010 (Local Identifier: 255-PS, National Archives Identifier: 6016402), demonstrates this reliance on glass as late as the middle of the 20th century. The series includes 14”x14” glass plates, like the one pictured here, used by the Palomar Observatory in California in their first Palomar Observatory Sky Survey conducted during the 1950s.

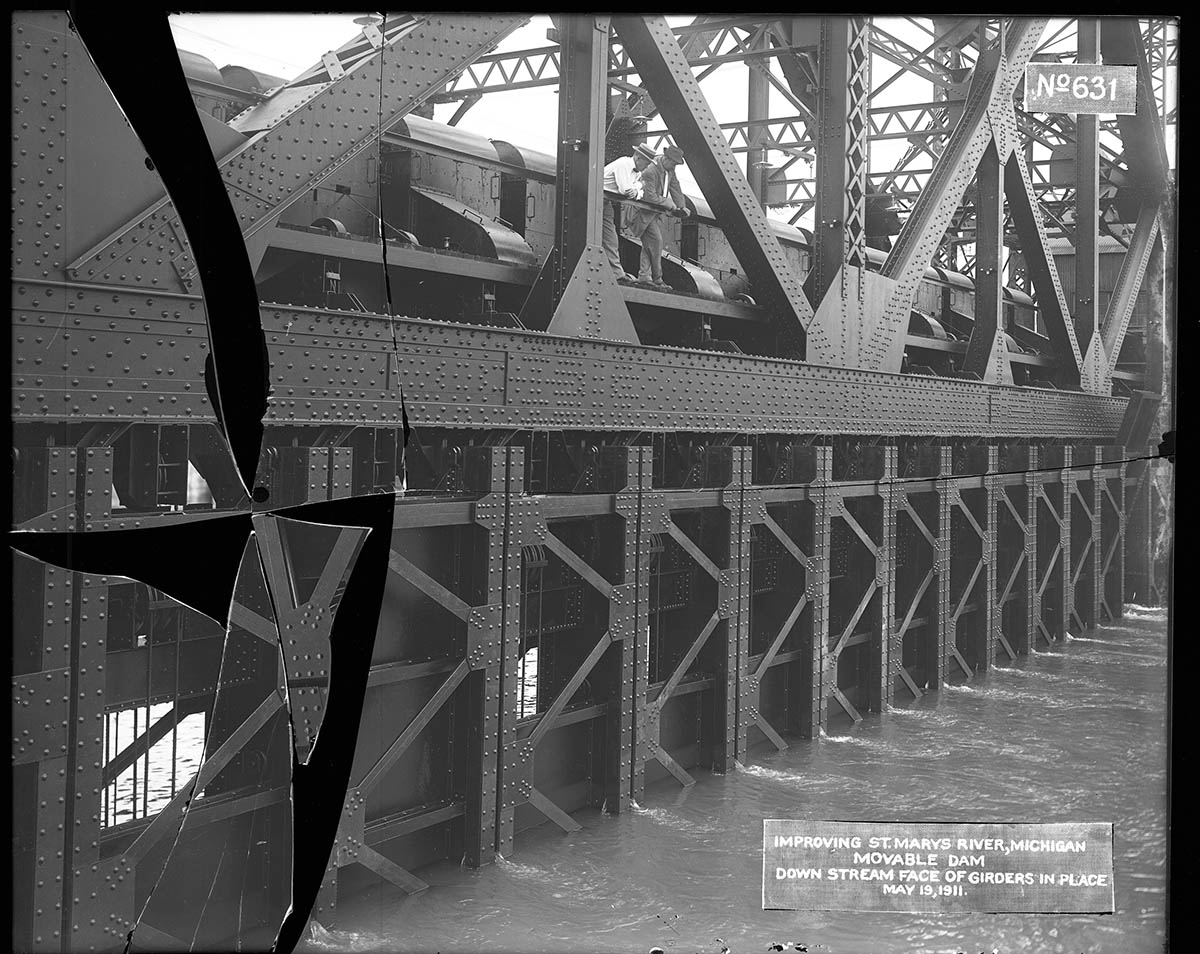

If not handled or stored correctly, glass can crack. Handling glass at any point in the item’s life cycle — from the 19th century photographer to the original recipient and then onto the repository responsible for maintaining and preserving it — increases the possibility of damage to the glass negative or slide. Broken and cracked slides not only diminish the aesthetic quality of the image but can also lead to a loss of part of the image and therefore loss of information within the record (similar to a piece of paper missing text due to a corner torn off). To the right is an example of cracks and image loss within a 1911 glass plate negative. Another issue you might find with glass is emulsion flaking due to poor storage conditions.

To minimize the handling of these fragile items while increasing access to them at the same time, the Still Picture Branch continues to digitize many series of glass negatives and lantern slides and make them available in the National Archives Catalog. The following describes processes used in creating the glass negatives and slides maintained within Still Picture Branch holdings and highlights several digitized series.

Wet-Collodion Glass Plate Negative

History of the Wet-Collodion Glass Plate Negative

Invented by Englishman Frederick Scott Archer with his findings published in 1851, the wet collodion process emerged as the most popular photographic process of the mid-19th century and remained so until it was largely replaced by the gelatin dry plate process in the 1880s.

To create a wet collodion glass plate negative, photographers made and cleaned their own glass plate; they then coated the plate with a solution of cellulose nitrate, or collodion, and a soluble iodide before bathing it within a silver nitrate solution. Time was a critical factor in this process because the plate needed to still be wet when exposed (most often with sunlight) within the camera; it then quickly developed and fixed before a protective varnish was applied. Having only about 15 minutes between initially coating the plate and developing the image before the plate dried, photographers carted the equipment and chemicals in portable darkrooms that accompanied them to the field.

Several identifying characteristics of wet collodion glass plates emerge from this process, which is heavily reliant on the individual photographer. Plates may have rough-cut edges resulting from the hand-made aspect. Fingerprints or blacked-out corners from the photographer or camera holding the plate can occasionally be seen. And some images may include liquid outlines, or pour lines, near the edges as the collodion was poured off the plate.

National Archives Holdings

The Still Picture Branch maintains several series of wet collodion glass plate negatives. Many of these series have been digitized in their entirety and made available in the National Archives Catalog. Of these, the most well-known are the photographs created by photographer Mathew Brady and his associates documenting the Civil War period. This includes the Mathew Brady Photographs of Civil War-Era Personalities and Scenes, 1921-1940 (Local Identifier: 111-B, National Archives Identifier: 524418) and the Photographs Relating to the Civil War, 1921-1921 (Local Identifier: 111-BZ, National Archives Identifier: 530506). For further information and links to resources on the Brady images, visit the Still Picture Branch’s Civil War Photographs web page.

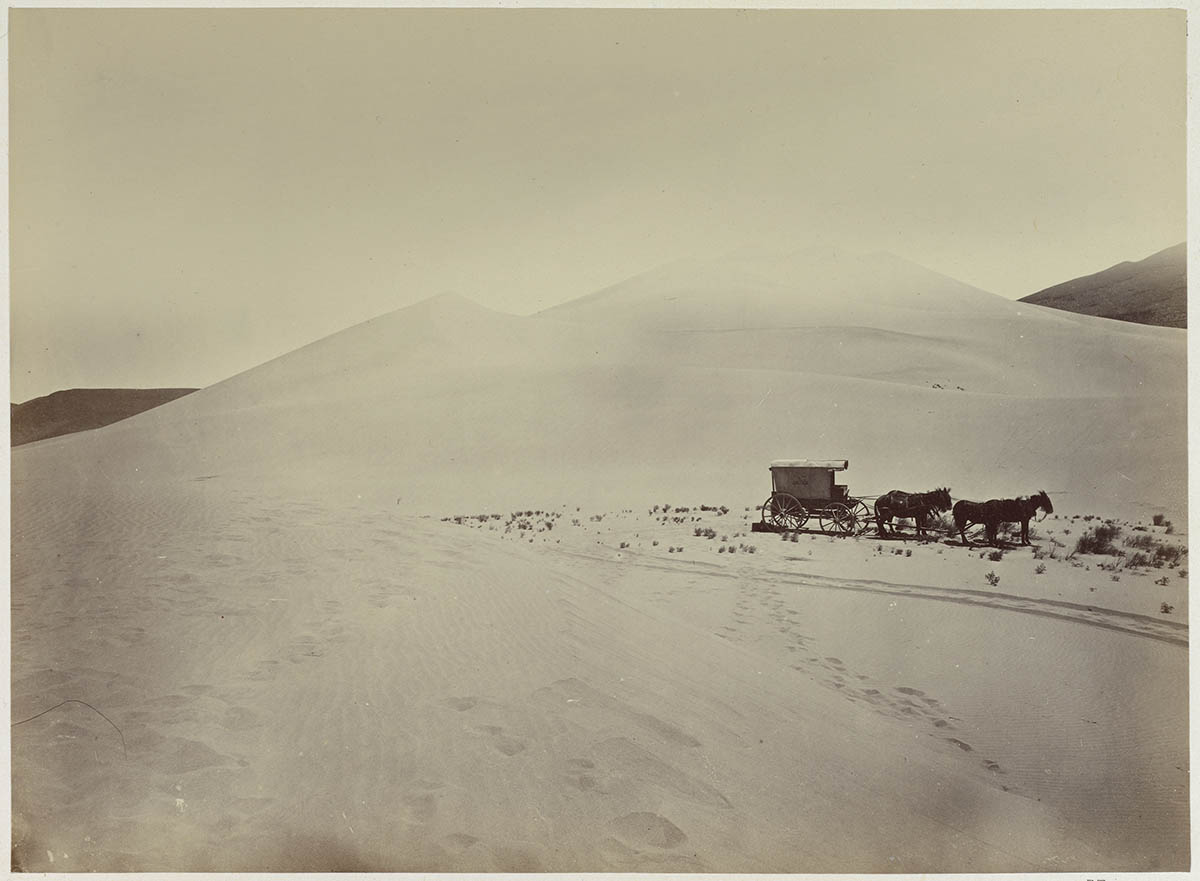

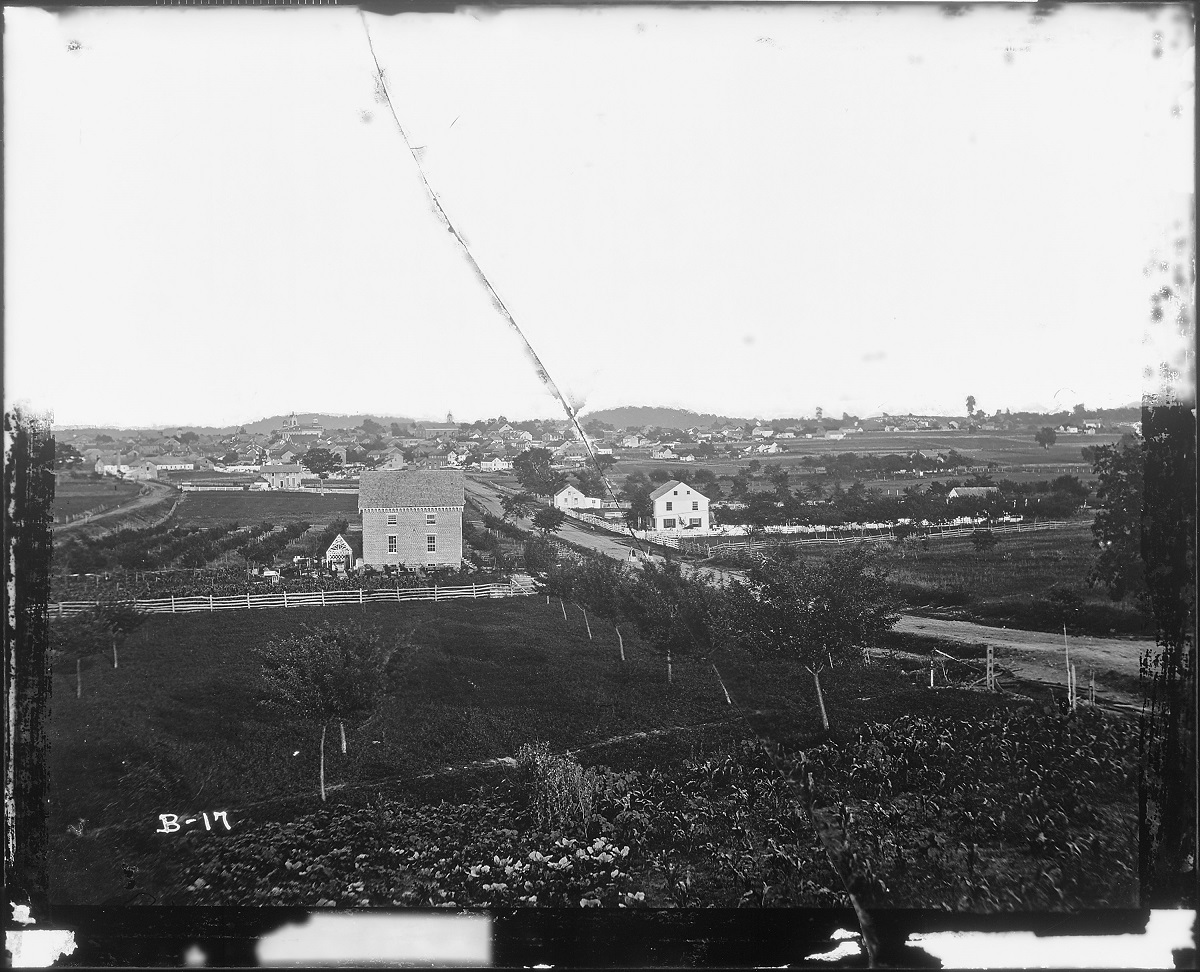

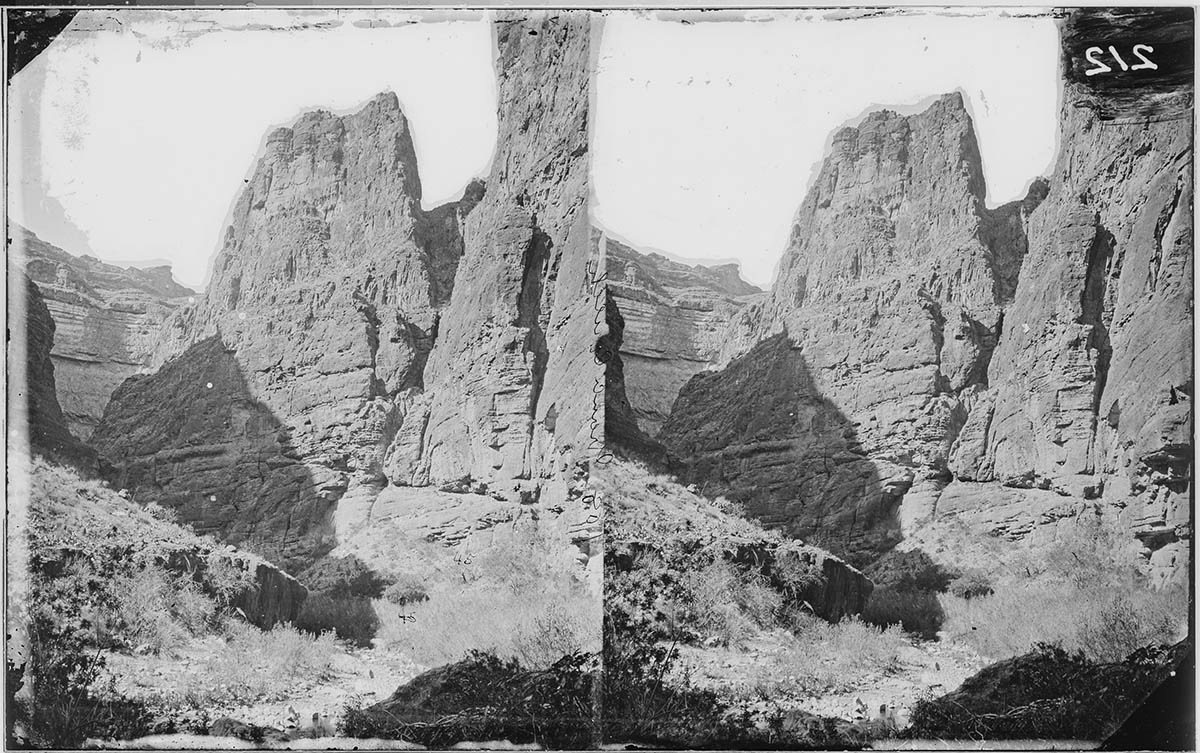

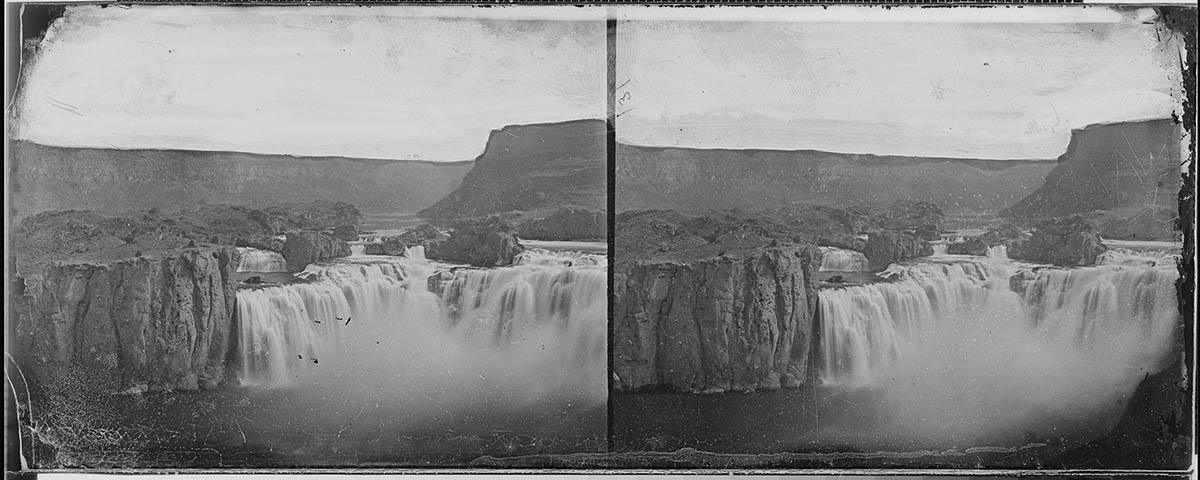

Other series of wet collodion glass plates focus on U.S. government-led surveys undertaken to learn more about the country’s land and natural resources, particularly the states and territories of the West. Survey teams hired photographers such as John K. Hillers, William Henry Jackson, and Timothy O’Sullivan to provide the visual documentation to accompany their examination of the region’s geography, geology, and topography. Below are images from three of these surveys.

Imagine carting your darkroom to these locations. The rugged and varied terrains pictured in these survey series further highlight the technical knowledge and skill needed by 19th century photographers using the wet collodion process.

Fully and Partially Digitized Series:

- Hayden Survey, William H. Jackson, Photographs, 1869-1878 (Local Identifier: 57-HS, National Archives Identifier: 516606)

- Photographs Taken by John K. Hillers during the Powell Survey and other Geological Surveys, ca. 1879-ca. 1900 (Local Identifier: 57-PS, National Archives Identifier: 517734)

- Photographs of the Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel from the King Survey, 1867-1872 ((Local Identifier: 77-KN, National Archives Identifier: 519442)

- Geographical Explorations and Surveys West of the 100th Meridian, 1871-1873 (Local Identifier: 106-WA, National Archives Identifier: 523880)

- Geographic Explorations and Surveys West of the 100th Meridian, 1871-1874 (Local Identifier: 106-WB, National Archives Identifier: 524104) (Partially Digitized)

- Mathew Brady Photographs of Civil War-Era Personalities and Scenes, 1921-1940 (Local Identifier: 111-B, National Archives Identifier: 524418)

- Civil War-Era Photographs, ca. 1921 (Local Identifier: 111-BA, National Archives Identifier: 530485)

- Photographs Relating to the Civil War, 1921-1921 (Local Identifier: 111-BZ, National Archives Identifier: 530506)

Gelatin Dry Plate

History of the Gelatin Dry Plate

The gelatin dry plate process invented by Richard L. Maddox became commercially available around 1879 and did not require portable darkrooms or the 15 minutes of processing time. Plates were coated with a liquid gelatin emulsion containing silver bromide crystals and then left to dry. Unlike the wet collodion process, the image did not need to be developed immediately after exposure. Exposure time within the camera was very short (one second or less) and the image could then be developed in a darkroom.

The cellulose plastic film (i.e., rolled film) that dominated photography during much of the 20th century emerged as an alternative to glass as a support material in the 1890s. As such, the gelatin emulsion technology used in the gelatin dry plate process, and later with cellulose film, can be seen as one of the most important advancements in the history of photography.

Silver image oxidation (silver mirroring) visible as a metallic sheen in reflective light, is a common deterioration characteristic of gelatin dry plates. This circa 1900 image from the records of the War Department’s Office of the Chief of Engineers shows silver mirroring across the top edge and at the right edge center.

National Archives Holdings

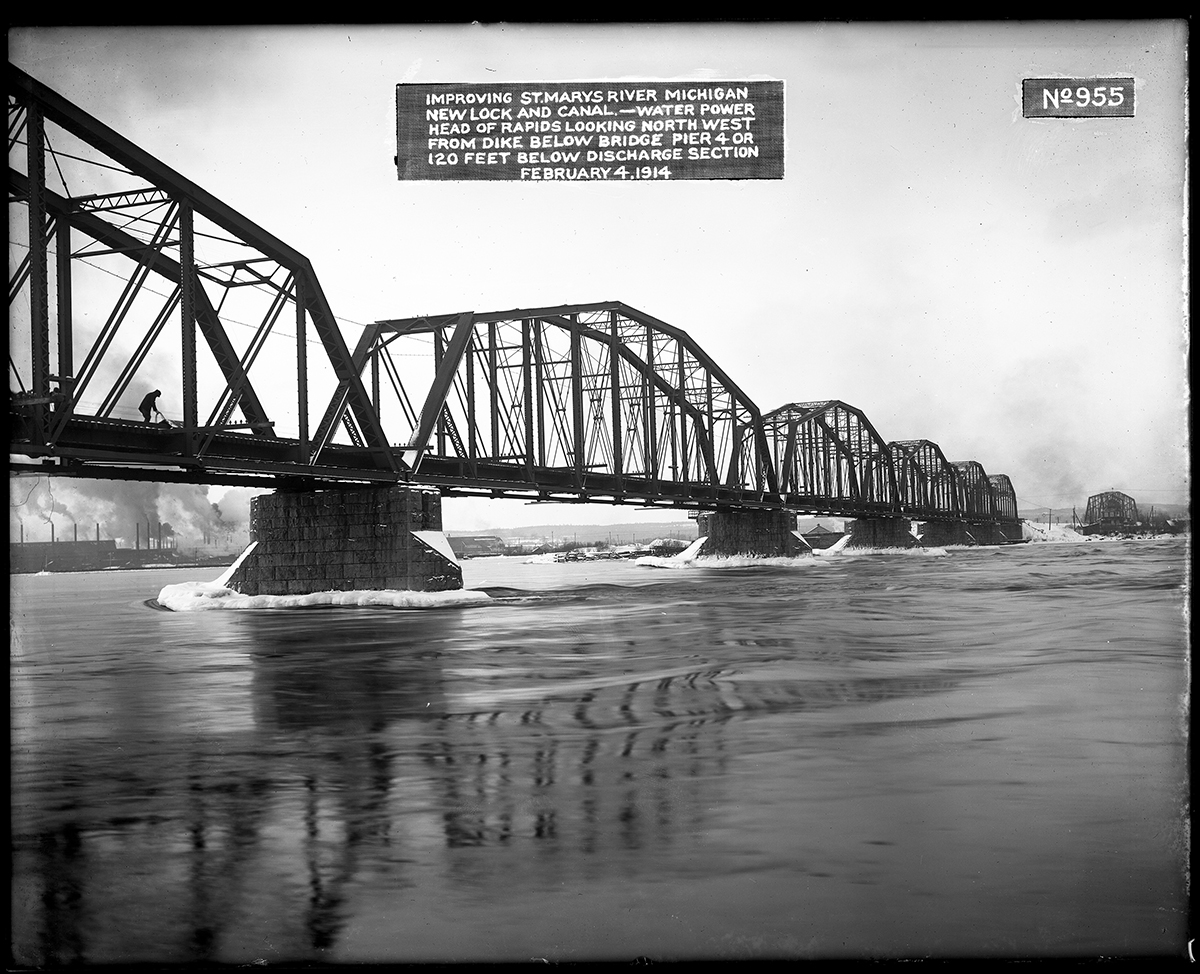

Gelatin dry plate negatives remained popular into the 20th century, so the series maintained within Still Picture Branch holdings primarily date to this 1880–1920 period. Several of these series have been digitized in part or in their entirety and are available in the National Archives Catalog. Here is a selection of images from these series.

Fully and Partially Digitized Series:

- Indian Life on the Western Reserve, ca. 1914-1917 (Local Identifier: 75-GIR, National Archives Identifier: 518932)

- Activities Files Photographs (Chief of Engineers), ca. 1875-1912 (Local Identifier: 77-A, National Archives Identifier: 519382)

- Construction and Renovation Photographs of St. Marys Falls Canal and Locks, ca. 1889-1941 (Local Identifier: 77-SOO, National Archives Identifier: 43862503)

- Photographs of the Norfolk Naval Shipyard, 1890-1952 (Local Identifier: 181-V, National Archives Identifier: 40038183)

- Miscellaneous Photographs, ca. 1919-1934 (Local Identifier: 242-HF, National Archives Identifier: 540167) from National Archives Collection of Foreign Records Seized, 1675-1958

- Photographic Prints of Buildings, Grounds, and People (St. Elizabeth’s Hospital), 1870-1920 (Local Identifier: 418-G, National Archives Identifier: 558494)

Portions of Glass Plates Digitized within These Series:

- Photographs of U.S. and Foreign Naval Vessels, 1883-1972 (Local Identifier: 19-NN, National Archives Identifier: 513052)

- Photographs of American Military Activities, ca. 1918-1981 (Local Identifier: 111-SC, National Archives Identifier: 530707)

- Photographs of Federal and Other Buildings in the United States, 1857-1942 (Local Identifier: 121-B, National Archives Identifier: 532288)

Lantern Slides

Many of the lantern slides in Still Picture Branch holdings are positive transparencies on glass, but some later versions contain a film transparency sandwiched between two pieces of glass and taped together. Lantern slides were especially popular from the 1880s through the 1920s. The earliest were not photographs but paintings on glass. Lantern slides are more commonly associated with the gelatin dry plate process (there were also collodion lantern slides). The plates were prepared with the silver gelatin emulsion and then exposed to a glass plate negative which resulted in a positive image. Another piece of glass covered the image for protection and the two were joined by tape along the edges.

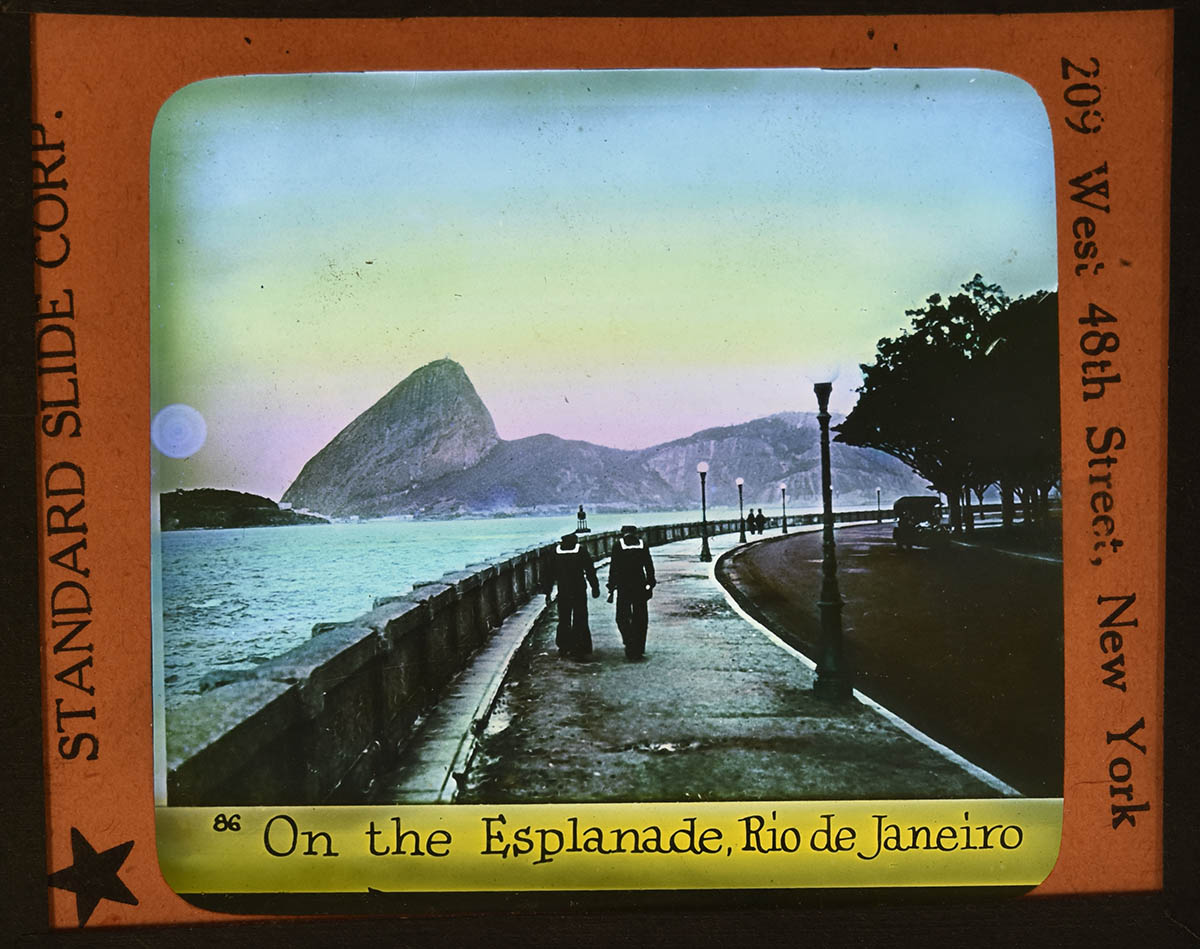

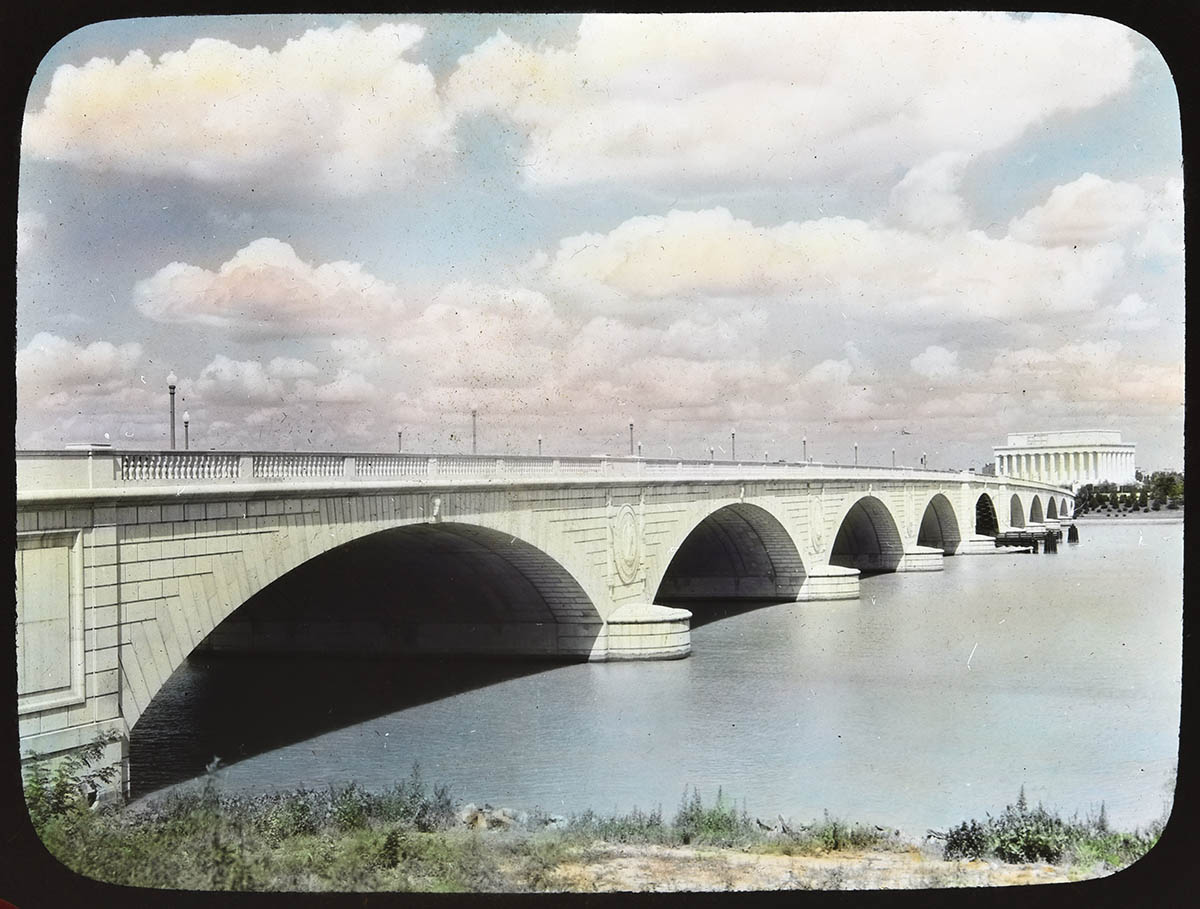

Lantern slides were placed in “magic lanterns,” the forerunner to the popular slide projectors of the second half of the 20th century, and could be projected using a light source. Lantern slides were often grouped as collections focused on a specific subject and as part of presentations, for educational, informational, and entertainment purposes. Captions or titles could be added to the slides to further this. The series “Hand-Colored Lantern Slides Made for Naval Recruiting Purposes ca. 1920” (Local Identifier: 24-RSC, National Archives Identifier: 513154) demonstrates this emphasis on presentations. Each slide includes a caption or title, and the series of slides were likely used to show potential recruits the places they could visit and things they could do if they joined the Navy.

National Archives Holdings

Still Picture Branch holdings contain numerous series that include lantern slides, in both black-and-white and color. Many have been digitized and are available through the National Archives Catalog, with more to be added in the future. Here are some examples of digitized lantern slides from series maintained by the Still Picture Branch.

Examples of Fully and Partially Digitized Series:

- Panama-Pacific International Exposition, 1915-1915 (Local Identifier: 16-SFX, National Archives Identifier: 512822)

- War Hemp Industries, 1942-1946 (Local Identifier: 16-WH, National Archives Identifier: 512830)

- Lantern Slides made for Naval Recruiting, ca. 1920 (Local Identifier: 24-RSB, National Archives Identifier: 513153)

- Hand Colored Lantern Slides Made for Naval Recruiting Purposes, ca. 1920 (Local Identifier: 24-RSC, National Archives Identifier: 513154)

- Photographs of Lighthouses, ca. 1913 (Local Identifier: 26-LGL, National Archives Identifier: 513240)

- Miscellaneous Merchant Ships, ca. 1930 (Local Identifier: 26-MLS, National Archives Identifier: 513249)

- Bureau of Engraving and Printing Facilities and Activities, 1917 (Local Identifier: 56-AE, National Archives Identifier: 516573)

- Lifesaving Service Activities and Equipment, 1918, ca. 1918-1947 (Local Identifier: 56-AL, National Archives Identifier: 516574)

- Photographs of Revenue Cutter Service Cadets, Ships, and Activities, 1900-1915 (Local Identifier: 56-AR, National Archives Identifier: 516575)

- Photographs of Treasury Department Personnel, Facilities and Activities, 1804-1917 (Local Identifier: 56-AT, National Archives Identifier: 516576)

- Henry Peabody Collection, 1959-1960 (Local Identifier: 79-HPS, National Archives Identifier: 520075)

- Scenes of Washington DC, ca. 1933-1936 (Local Identifier: 79-LS, National Archives Identifier: 520090)

- J. M. Moon Collection of Lincolniana, 1809-1865 (Local Identifier: 165-JM, National Archives Identifier: 533229)