Restricting Immigration from Asia and the Pacific, 1870s to 1950s

Early immigration laws placed significant restrictions on migration from Asia and Pacific Islands (API) to the United States. These regulations led to increased scrutiny by immigration officials and the creation of numerous documents. Records concerning certain groups, such as immigrants and U.S. citizens of Chinese descent, can offer a rich source of information. However, it is important to recognize that not all records were created equally for every immigrant group. This page provides an overview on how federal policies uniquely impacted API migrants, explores the key federal agencies responsible for enforcing these stringent immigration laws, and provides guidance for accessing immigration records held at the National Archives.

Legislating Immigration

Restrictive immigration policies exerted considerable influence on the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) experience. Legislation enacted between 1875 and 1965 excluded almost all immigration from Asian countries, stunting the growth of AAPI communities across the United States. Laws targeting specific communities gave rise to certain types of records at different periods in early U.S. immigration history. This helps to explain why some documentation may not exist for every API immigrant.

The following is a brief overview on the policies that most impacted immigrants of Asian and Pacific Islander descent.

Page Act of 1875

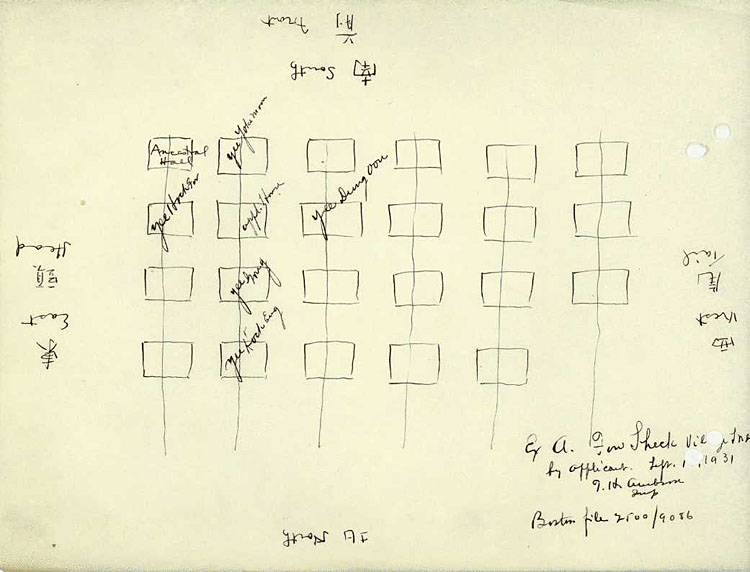

Despite presenting documentation of their exempt status, Chinese women were subjected to interrogations questioning their moral turpitude. Case File for Lew Bow Kong (National Archives Identifier: 19086706).

Immigration Act of 1882

Passed a few months after the Act of May 1882, the Act of August 1882 (uscis.gov/) prohibited the entry of individuals likely to become “a public charge.” This law barred those lacking  the means to support themselves, whether referring to a person’s financial resources or medical condition. Though it did not explicitly exclude immigrants based on race, enforcement conflated “undesirable immigrants” with the poor and diseased bodies—prejudices historically applied to Asian immigrants. The public charge doctrine has been expanded in subsequent immigration policies and continues to be enforced today.

the means to support themselves, whether referring to a person’s financial resources or medical condition. Though it did not explicitly exclude immigrants based on race, enforcement conflated “undesirable immigrants” with the poor and diseased bodies—prejudices historically applied to Asian immigrants. The public charge doctrine has been expanded in subsequent immigration policies and continues to be enforced today.

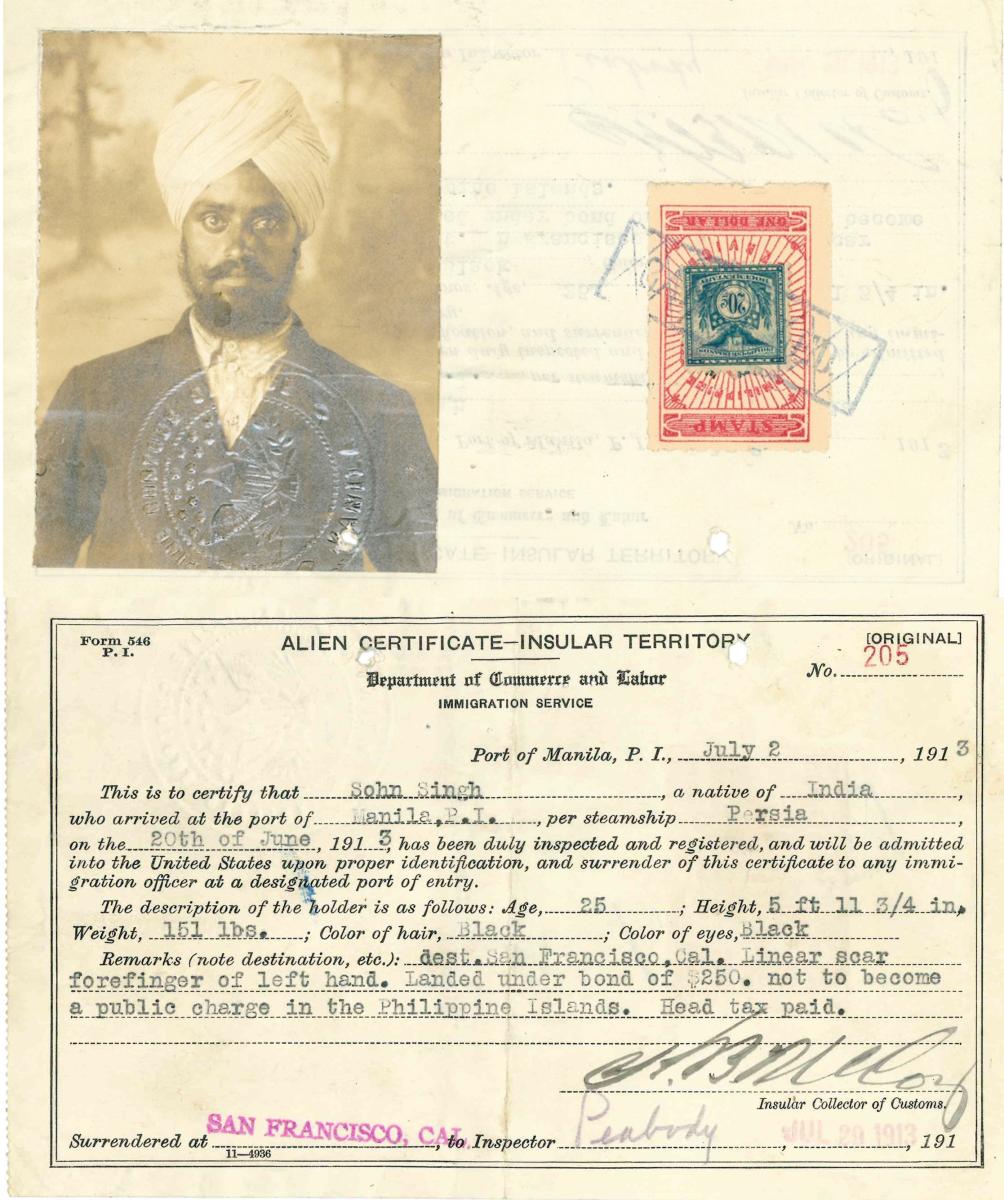

Sohn Singh was detained due to a hookworm (uncinariasis) diagnosis. Despite filing a writ of habeas corpus, Singh and several other Indian immigrants were deported. Arrival Case File 12815/008-11 (National Archives Identifier: 28817900).

Immigration Act of 1917

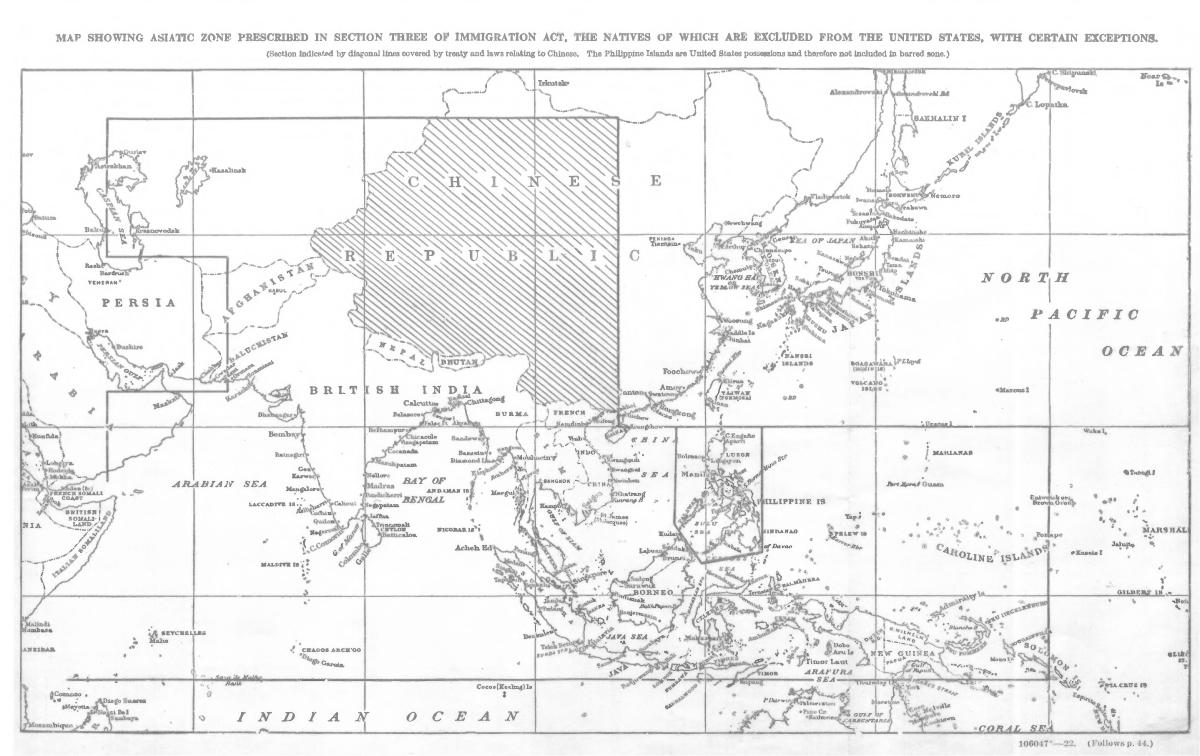

Immigration Act of 1917 (loc.gov/) became the first widely enacted law that implemented a literacy test and restricted immigration from the geographically designated “Asiatic Barred Zone.” Loosely defined as “any country not owned by the U.S. adjacent to the continent of Asia,” the barred zone extended from parts of West Asia to Western China and extended north into parts of Russia and southwest to the Pacific Islands. Japan, the Philippines, and other U.S. territories in the Pacific, were excluded from the barred zone. The 1917 law made exemptions for professionals and students, and their families. This act was amended in 1924.

in the Pacific, were excluded from the barred zone. The 1917 law made exemptions for professionals and students, and their families. This act was amended in 1924.

Asiatic Barred Zone Map from Immigration Laws, Rules of May 1, 1917, USCIS Historical Library .

Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934

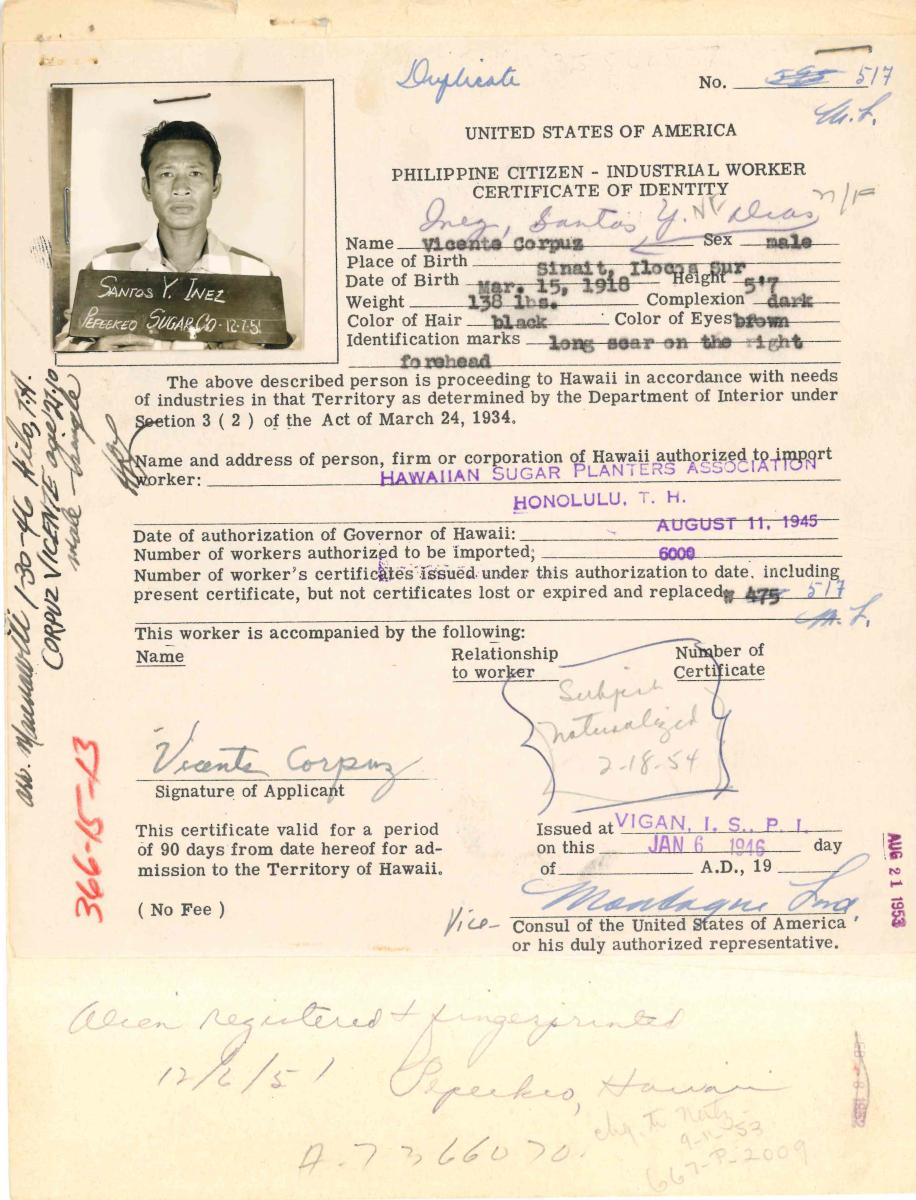

While this statute initiated the process for eventual independence in the Philippine Islands (that took effect in July 1946), it also restricted migration to the U.S. mainland by reclassifying Filipino arrivals from U.S. nationals to aliens and established an annual immigration quota of 50. At the urging of sugar planters, the law made exemptions for the Territory of Hawai’i, and the large recruitment of Filipino labor remained uninterrupted until 1946.

Despite these attempts to staunch the flow of migration from Asia and the Pacific, nearly every policy allowed exemptions to admit otherwise excludable individuals. Though the number of immigrants from this region remained nominal compared to other groups, tenacious emigrants continued to arrive while claiming an exempt category.

Vicente Corpus arrived in Hawai’i as one of the last group of contracted laborers admitted. Filipino Contract Worker Certificate of Identity No. 517 (National Archives Identifier: 241089565).

1882 Chinese Exclusion Act

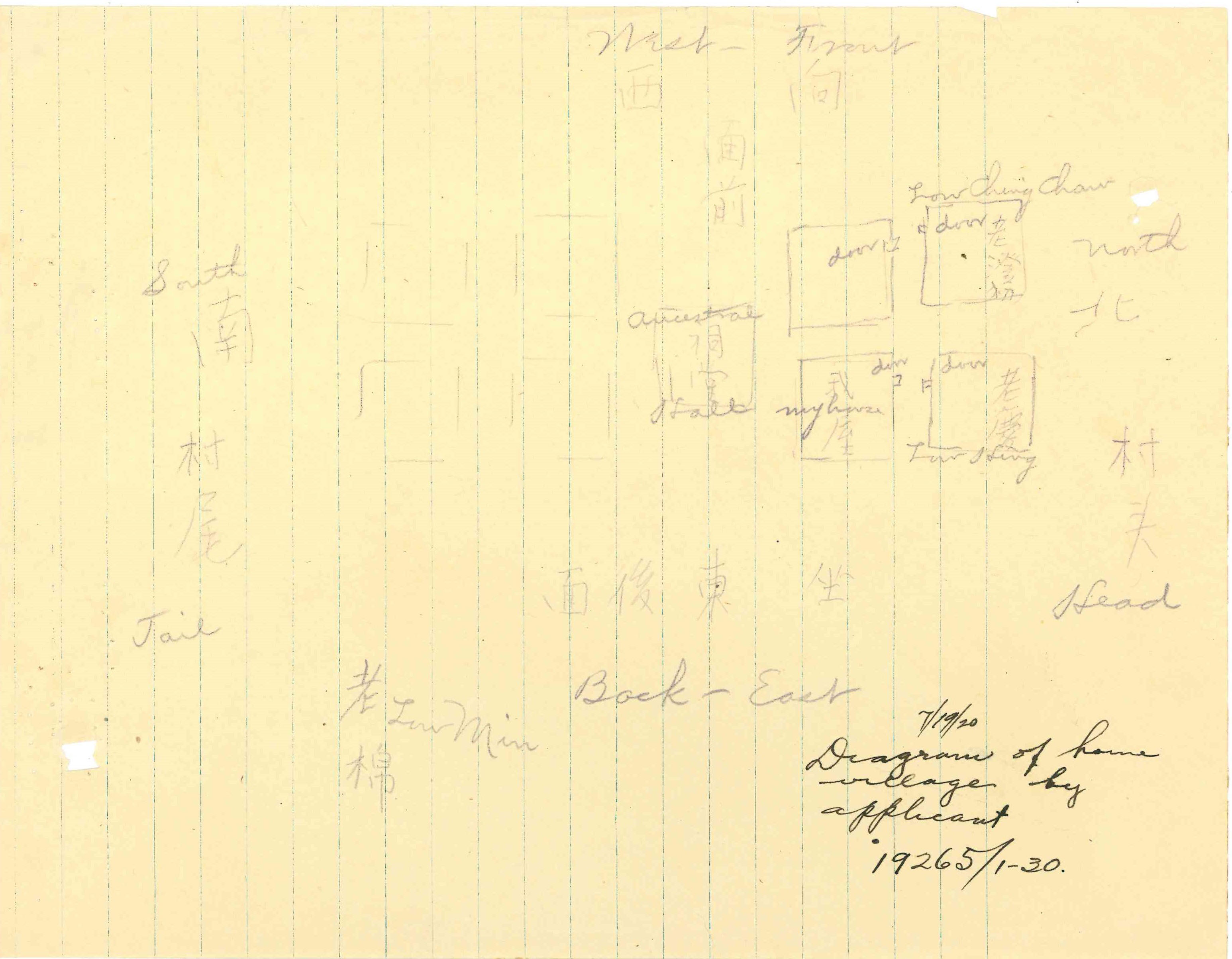

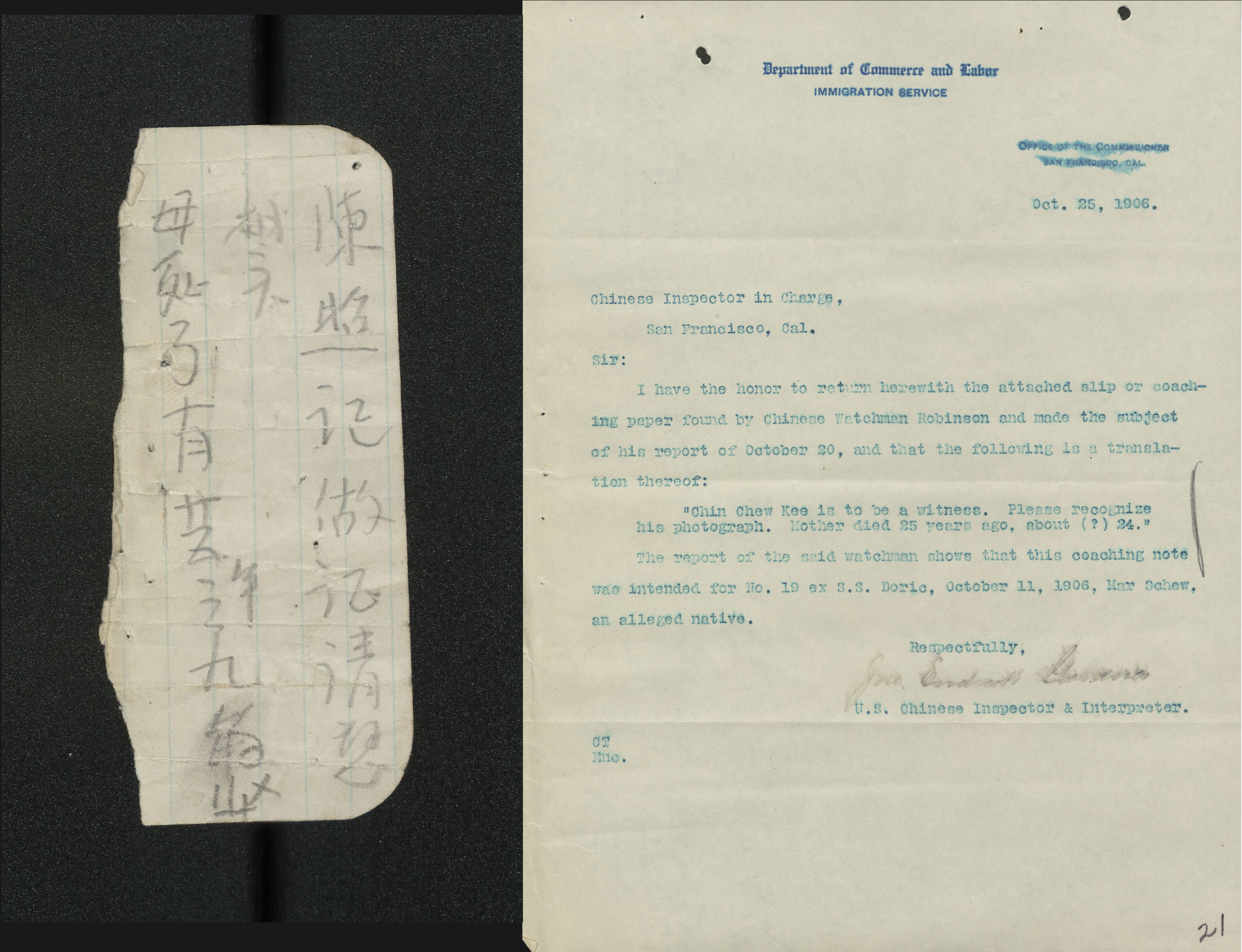

The Chinese Exclusion Act (passed on May 6, 1882) was the first in a series of race- and class-based legislation that cemented exclusionary measures against Chinese immigrants. Though it specifically targeted Chinese laborers, enforcement placed a heavy burden on all Chinese persons. Despite presenting documents confirming their U.S. citizenship or exempt status (i.e., merchants, students, clergy, and their families), Chinese arrivals were subjected to interrogations that scrutinized their lawful statuses, identification, and familial relationships. As the laws expanded and reduced exempt categories, enforcement progressively became more stringent.

As the only set of race-specific immigration policies enforced, the Chinese  Exclusion Acts affected any person of Chinese descent—regardless of their nationality. These policies provided the framework to develop laws applied to other groups. The Act of May 1882 was extended several times through the end of the 19th century, then made permanent in 1904, and finally repealed in 1943.

Exclusion Acts affected any person of Chinese descent—regardless of their nationality. These policies provided the framework to develop laws applied to other groups. The Act of May 1882 was extended several times through the end of the 19th century, then made permanent in 1904, and finally repealed in 1943.

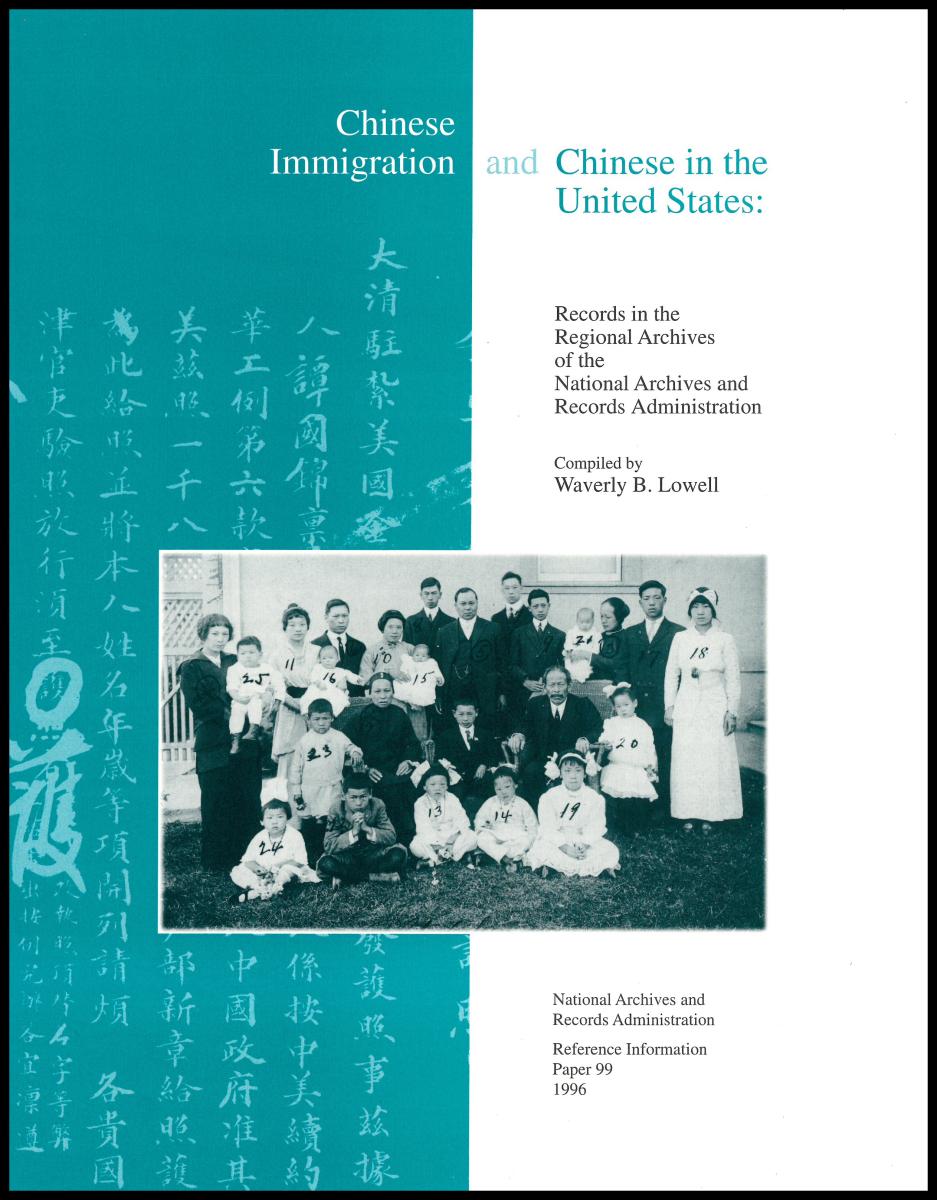

For more information on how numerous federal agencies interpreted and enforced the Chinese Exclusion Acts, see the 1996 reference information paper, Chinese Immigration and the Chinese in the United States.

Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907

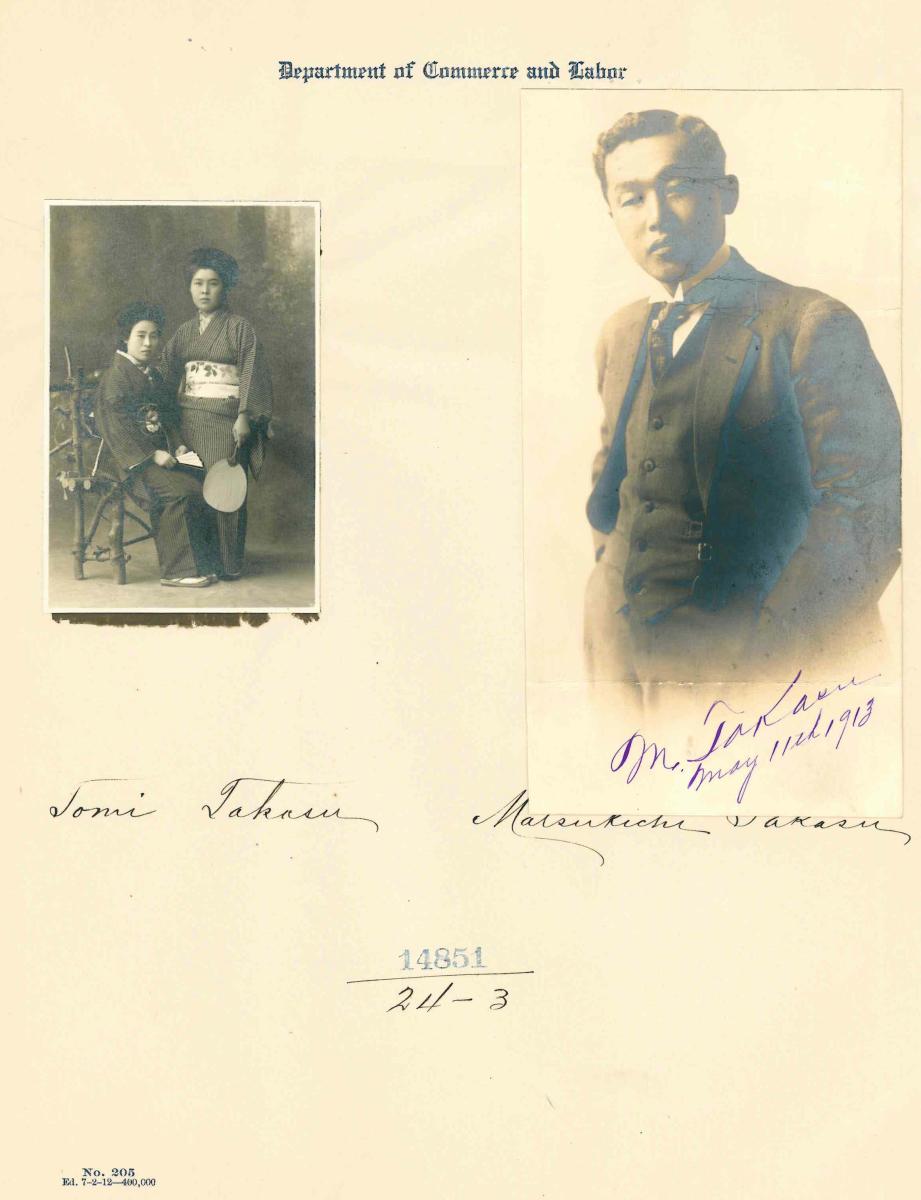

Announced under Executive Order 589, this 1907 diplomatic pact (history.state.gov/) restricted laborers from Japan and Korea. Unlike the Chinese Exclusion Act, this agreement allowed families of laborers already residing in the United States to immigrate.

Announced under Executive Order 589, this 1907 diplomatic pact (history.state.gov/) restricted laborers from Japan and Korea. Unlike the Chinese Exclusion Act, this agreement allowed families of laborers already residing in the United States to immigrate.

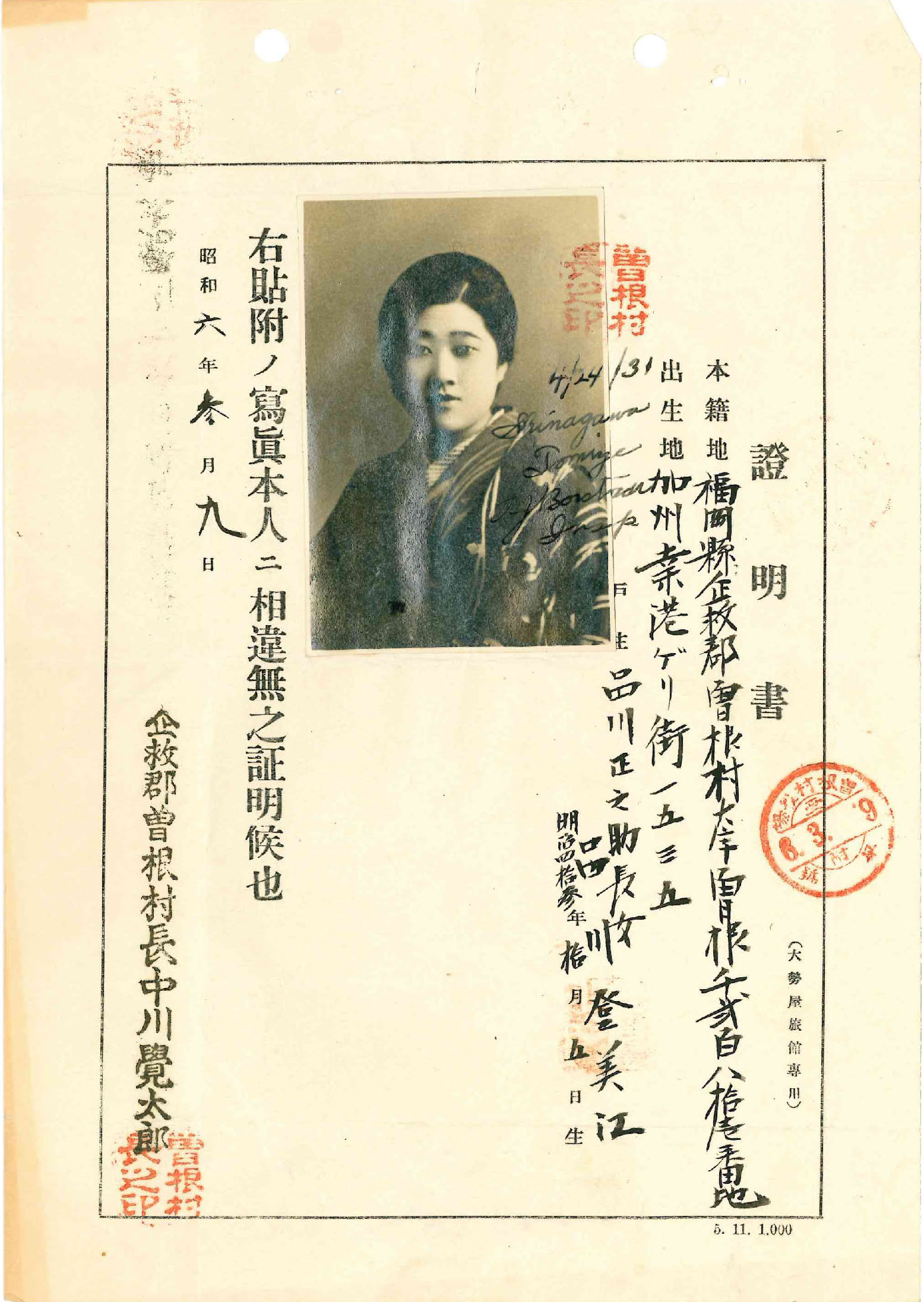

Tomi Takasu was one of many Japanese women who entered the United States as “picture brides,” which was part of customary marriage arrangements. Arrival Case File 14851/024-03 (National Archives Identifier: 28829402).

Immigration Act of 1924

The Immigration Act of 1924 (National Archives Identifier: 5752154) set a national origin quota to two percent of country-of-origin populations from the 1890 census. It also barred immigrants “ineligible for citizenship,” effectively prohibiting immigration from Asian countries. This law extended restrictive immigration policies to all Japanese citizens, negating the 1907 agreement (history.state.gov/).

Naturalization was finally extended to AAPI persons in the 1940s and 1950s. This opened immigration, but it was still limited by set quotas. National origin quotas were not fully lifted until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

Despite the quota system, Asian immigrants continued to be admitted with non-quota visas, either as returning residents or family members of those already residing in the United States. Helen Hisayo Nambu, Investigative Case File 4518/0006 (National Archives Identifier: 285450750).

Enforcing Immigration Restrictions

U.S. Customs Service (Record Group 36)

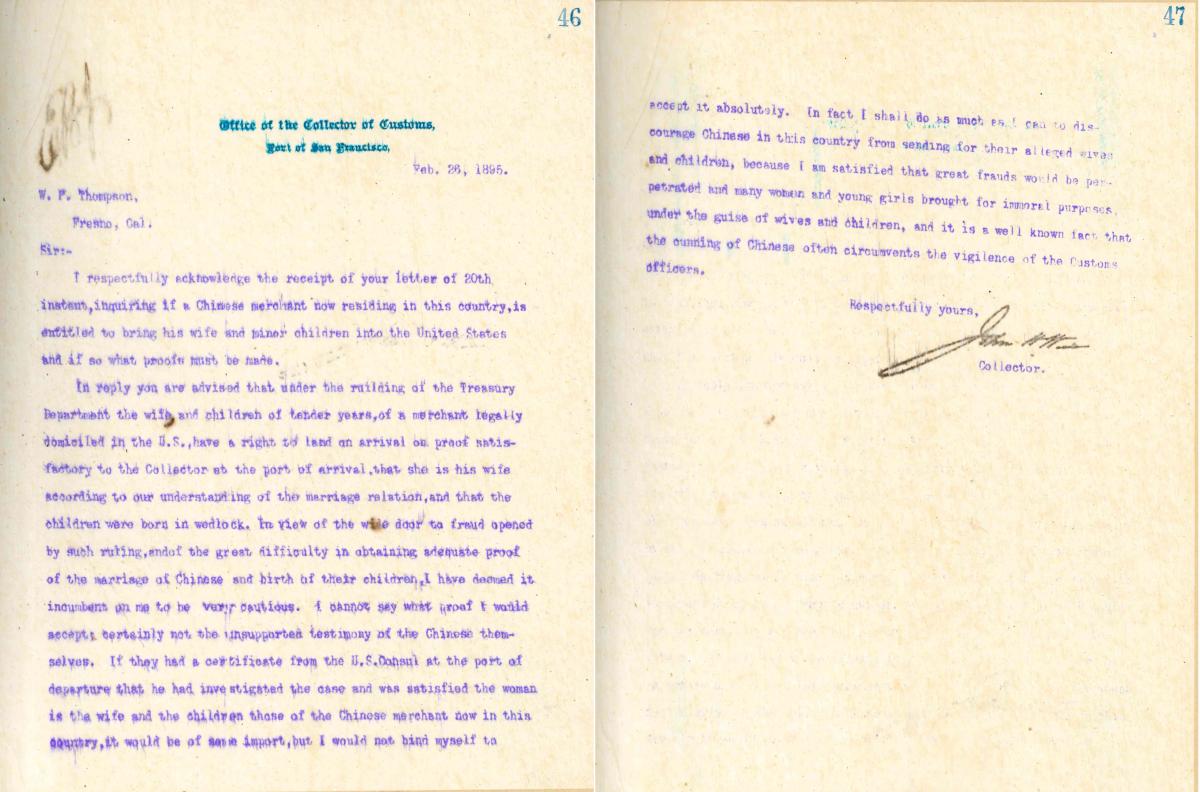

With no federal immigration administration in place prior to 1882, the Collectors of Customs became the first officials tasked with enforcing immigration laws at ports throughout the United States. While a separate immigration office was established in 1891, customs officials continued to hold jurisdiction over Chinese arrivals until 1900—when these responsibilities were transferred to the Commissioner-General of Immigration. The Collectors of Customs still maintained final approval over local Chinese Bureau investigations until 1903, when the Bureau of Immigration became part of the newly created Department of Commerce and Labor.

Lacking formalized procedures, U.S. Customs Service relied on its local officials to interpret immigration laws and develop policies as they saw fit. Because strict exclusionary policies required further scrutiny on Chinese arrivals, many of the activities and opinions of customs officials are documented in correspondence and policy records.

and develop policies as they saw fit. Because strict exclusionary policies required further scrutiny on Chinese arrivals, many of the activities and opinions of customs officials are documented in correspondence and policy records.

Customs Service records are a great resource for historical research and policy decisions related to the enforcement of early exclusionary regulations. While regional offices did not retain individual case files, case files can be found in the records to the Customs Headquarters (Indexes to Case Files and Correspondence Files).

Wise noted that all Chinese women, even those with exempt status, would be assumed to be “brought for immoral purposes under the guise of wives and children.” Letter from John H. Wise, Collector of Customs to W.F. Thompson, 2/26/1895 (National Archives Identifier: 29007754).

Immigration and Naturalization Service (Record Group 85)

In 1900, the Bureau of Immigration became the chief agency responsible for implementing federal regulations, and consolidated immigration enforcement within one agency. This office eventually evolved into the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS).

The INS inherited the early case files created by customs officials and continued to generate an enormous volume of individual case files—as they actively applied various immigration laws with every new policy enacted. Records from Record Group 85 serve as a vital source for genealogical research and in-depth examination of individual case files.

Note: Most regional INS administrative records no longer exist, except for correspondence with INS Headquarters (INS Subject and Policy Files).

Researching the Records

To begin your research, search for potential immigration records from the National Archives Catalog. If you are able to locate a Catalog record related to your individual, please contact the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) office identified under the section “Archived Copy.”

If you are unable to locate an individual in the Catalog, you may wish to contact a NARA office for further assistance. Individual cases might not have been retained at the original entry port, as officials often shared documents between INS offices. Records might have been consolidated into a later INS file at a different port or at the INS office near the person's last known residence.

To determine which NARA office to contact, identify the most recent port of entry or last known residence. Then contact the closest National Archives office to this known location.

Sadly, files for many early API immigrants no longer exist. At many National Archives field offices, only segregated Chinese immigration files have survived. Records held at the National Archives in Washington, DC, and at San Francisco include case files for those immigrating from other parts of Asia and the Pacific.

For additional information on other types of immigration records, especially on Alien Files (A-Files), visit the Immigrant Records page.

The following is a list of Customs Service and INS records related to API immigration housed at NARA facilities across the country. Click the National Archives Identifier for more information on each record series. Scroll down to the bottom of each Catalog record for the NARA office contact details.

Click "+" to display more information:Explore Further

Blogs and Articles

Milestone Documents: Chinese Exclusion Act (1882)

Prologue magazine: “Broken Blossoms,” 2016

Prologue magazine: “Attachments: Faces and Stories from America's Gates,” 2012

Prologue magazine: “An Alleged Wife: One Immigrant in the Chinese Exclusion Era,” 2004

Prologue magazine: “Race, Nationality, and Reality,” 2002

Pieces of History blog: “AAPI Exclusion and the Case of Wong Kim Ark," 2024

Pieces of History blog: “Chinese Exclusion and the 1899 National Export Exposition,” 2021

Pieces of History blog: “Navigating the Law,” 2020

Pieces of History blog: “19th Amendment at 100: Mabel Ping-Hua Lee,” 2020

Pieces of History blog : “Chinese Exclusion Act Case Files and the USCIS Master Index,” 2017

National Archives News: “Chinese American Actress’s Story Illustrates ‘Othering’ of Immigrants,” 2021

AOTUS blog: “Immigration Records Illuminate the Story of Angel Island,” 2010

Education Updates blog: “Questioning Chinese Exclusion,” 2021

Education Updates blog: “Primary Sources Show How the Chinese Exclusion Act was Applied,” 2015

Education Updates blog: “Digitizing Chinese Immigration in Our New Innovation Hub,” 2015

The Text Message blog: "Sau Ung Loo Chan, An Advocate for American Citizenship and Immigrant Rights," 2024

The Text Message blog: “Bringing the Past to Light through the Chinese Exclusion Act Case Files,” 2021

Archives Library Information Center (ALIC): Online Databases, including onsite access to ProQuest, “Immigration: Records of the INS, 1880–1930”

History Hub: “Honolulu INS Office Filing System”

History Hub: “San Francisco INS Office Records”

History Hub: “Chinese American Identification Papers" (7-part blog series)

History Hub: “INS Central Office Records: Documenting Individuals from Asia and the Pacific”

Citizen Archivist Mission

Educator Resources

Public Programs

Oh, the Stories They Tell: Chinese Exclusion Acts

Case Files at the National Archives (2017 May 10)

Immigration Records & Privacy, (2015 Dec. 10)

Immigration: Barriers and Access, 2016

Asian Migration and the Hidden History of

Exclusion at Ellis Island, August 12, 2022

PDF files require the free Adobe Reader.

More information on Adobe Acrobat PDF files is available on our Accessibility page.