“I Have the Honor to Tender the Resignation . . .”

Spring 2010, Vol. 42, No. 1

By Trevor Plante

Many southern-born U.S. Army officers waited until their native states voted to secede from the Union before tendering their resignations. In some cases northern-born officers resigned their commissions and went south, and southern-born officers stayed true to the Union. The most famous cases are fellow Virginians Winfield Scott and George H. Thomas, who both remained with the Union, and John C. Pemberton, who although born in Philadelphia, joined the Confederacy.

In June of 1860 the U.S. Army had approximately 1,080 officers and 14,926 enlisted men. Of the 1,080 active Army officers, 286 resigned or were dismissed to enter Confederate service in 1861. Approximately 26 enlisted men violated their oaths and went south. There were 824 West Point graduates on the active list of Army officers. Of that number, 184 West Point graduates were among the 286 officers who offered their services to the Confederacy.

In December of 1860 there were 1,554 officers serving in the U.S. Navy. In 1861, 373 of these officers resigned. Of that number 157 were dismissed from the Navy. Approximately 311 became commissioned or warrant officers in the C.S. Navy. In early 1861, the United States Marine Corps had 1,775, men, including 63 officers. Nineteen of these officers tendered their resignations to join the Confederate States Marine Corps.

Several years ago, while on a vault tour at the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C., the daughter of the Vice President of the United States asked, after being shown Robert E. Lee’s resignation from the U.S. Army, why we chose to keep just that one. We responded that we have hundreds of resignations from officers of the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and those of cadets at West Point and Annapolis.

What follows are several examples of some of these resignations, some from famous officers, and some not. Many went on to become famous while fighting for the Confederacy.

Additional letters of resignation are featured in the new exhibit “Discovering the Civil War,” at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., starting April 30, 2010.

Capt. P.G.T. Beauregard, U.S. Army

Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard was born in Saint Bernard Parish, Louisiana, on May 28, 1818. He graduated second in his class at West Point in 1838. During the Mexican War, he served as an engineer officer on the staff of Gen. Winfield Scott and was honored several times for gallantry.

Beauregard was assigned as the Superintendant of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point on January 23, 1861, and then relieved a few days later on January 28. He wrote to the adjutant general from New Orleans on February p, 1861, “having ascertained positively on my arrival here that Louisiana, my native State, has withdrawn from the Union and resumed her State Sovereignty I tender to the President of the United States my resignation from the Army to take effect on the 1st [proximo] or sooner if practicable.” His resignation was accepted on February 20, 1861.

He was commissioned a brigadier general in the Confederate army on March 1, 1861. The following month, while commanding forces at Charleston, South Carolina, he ordered the bombardment of Fort Sumter, thus starting the American Civil War. He was promoted to full general following the battle of Bull Run (First Manassas). Throughout the Civil War, Beauregard clashed with his superiors. His Confederate career was highlighted by strong perfor-mances at the Battle of Shiloh following the death of Albert Sidney Johnston and during Ulysses S. Grant’s advance on Petersburg, Virginia, in June of 1864. He was paroled at Greensboro, North Carolina, on May 2, 1865.

Col. Robert E. Lee, U.S. Army

Probably the most famous resignation from the U.S. Army in the holdings of the National Archives is that of Robert E. Lee. Recently promoted to colonel of the First U.S. Cavalry, Lee resigned soon after the state of Virginia voted to secede from the Union.

On April 20, 1861, Lee wrote two letters, both from his home in Arlington, Virginia. One letter was his resignation from the Army addressed to Secretary of War Simon Cameron, in which Lee simply wrote, “I have the honor to tender the resignation of my commission as Colonel of the 1st Regt of Cavalry.” There was no reason given, and no explanation provided.

The second letter was addressed to Gen. Winfield Scott, commander-in-chief of the Army. This letter was lengthier than the previous correspondence, for Lee had a lifelong relationship with General Scott, one he did not share with the secretary of war. After informing Scott that he was tendering his resignation from “a service to which I have devoted all the best years of my life and all the ability I possessed,” he let his feelings for the aging general be known: “To no one, General, have I been as much indebted as to yourself for uniform kindness and consideration, and it has always been my ardent desire to meet your approbation. I shall carry to the grave the most grateful recollections of your kind consideration, and your name and fame will always be dear to me.”

The most quoted line from his letter followed next: “Save in defence of my native State, I never desire again to draw my sword.” Lee went on to become famous as the leader of the Army of Northern Virginia, held in high esteem, not only during the American Civil War, but throughout military history.

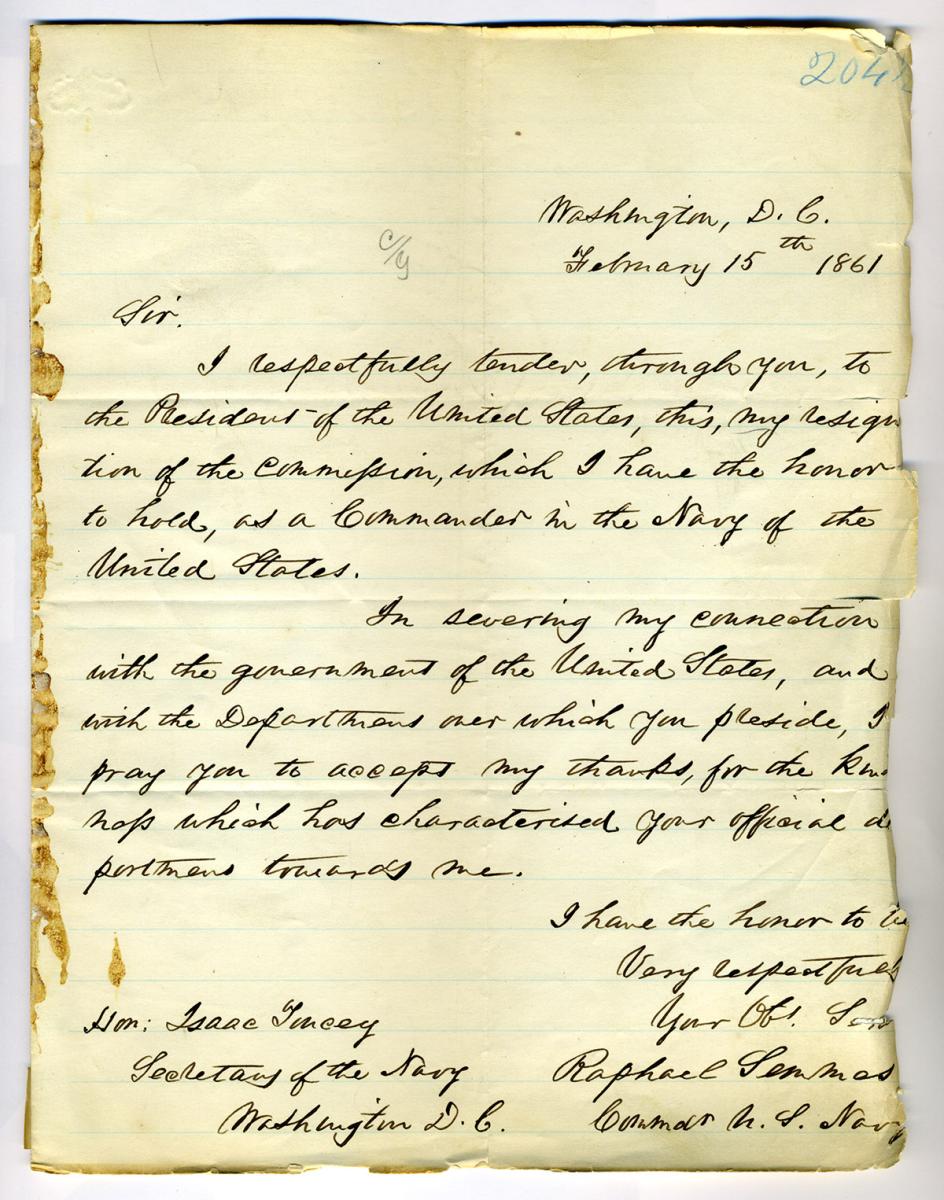

Commander Raphal Semmes, U.S. Navy

Raphael Semmes, born in Charles County, Maryland, in 1809, joined the Navy as a midshipman in 1826 and rose to the rank of commander in September of 1855.

Semmes submitted his resignation to Secretary of the Navy Isaac Toucey on February 15, 1861. After beginning the letter respectfully tendering his resignation, Semmes explains, “In severing my connection with the government of the United States, and with the Department over which you preside, I pray you to accept my thanks, for the kindness which has characterized your official deportment towards me.”

After resigning his commission, Semmes joined the Confederate navy and was commissioned a commander on March 26, 1861. He was later promoted to captain and rear admiral. He commanded the C.S.S Sumter from 1861 to 1862 and C.S.S. Alabama from 1862 to 1864. He is most renowned for the famous duel between the Alabama and the U.S.S. Kearsage off Cherbourg, France, on June 19, 1864. He later assumed command of the James River Squadron and the Semmes naval brigade. He was paroled at Greensboro, North Carolina, April 28, 1865.

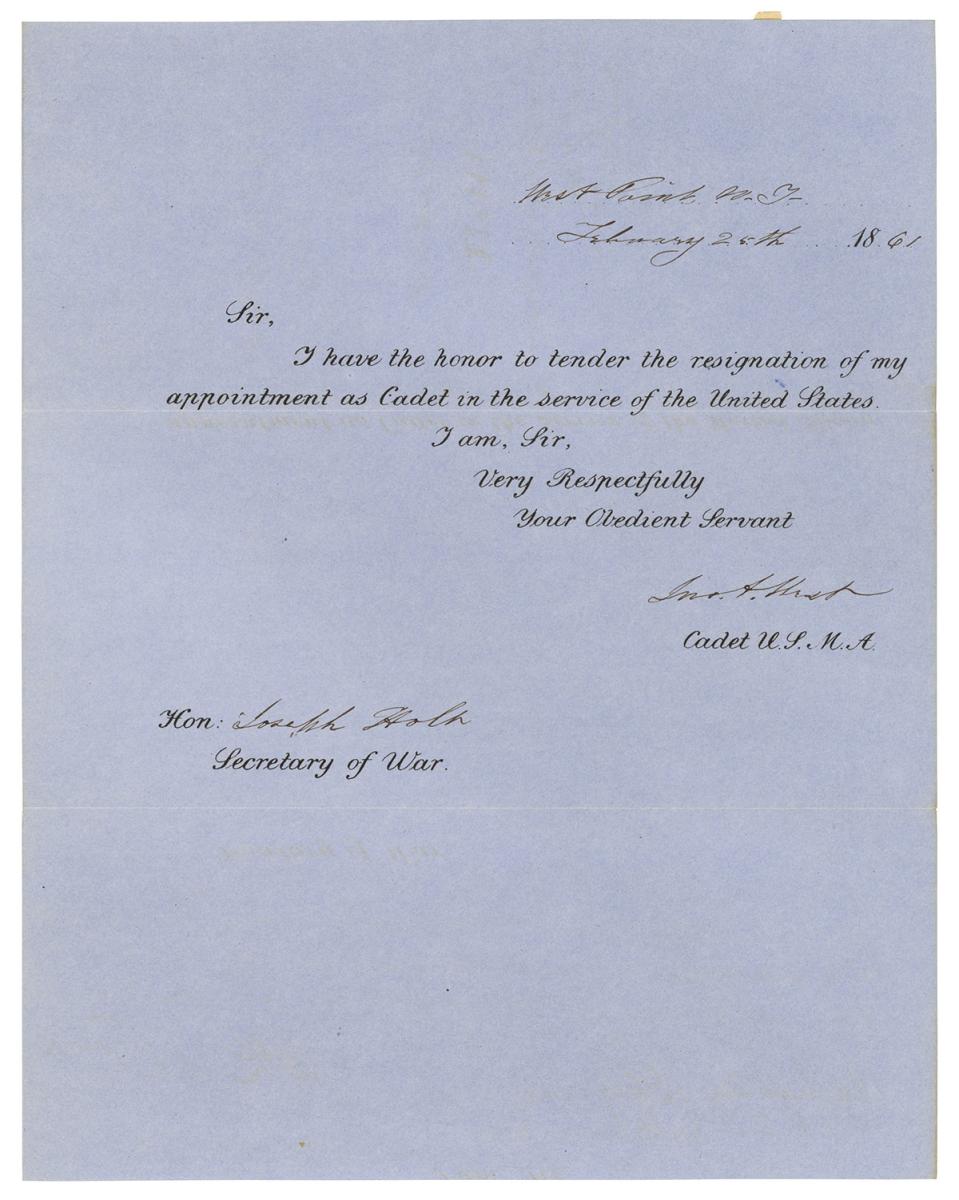

Cadet John A. West, U.S. Military Academy

John A. West began his quest of becoming a cadet at West Point by writing to Georgia Congressman Alexander H. Stephens in February of 1856. Stephens passed on the young man’s letter to Secretary of War Jefferson Davis. With a later recommendation from Congressman John Hill, representing the Seventh District of Georgia, West inked his name on his confirmation in Madison, Georgia, on February 9, 1858. He was granted his father’s permission and soon became a cadet at the U.S. Military Academy.

On January 19, 1861, the state of Georgia seceded from the Union. On February 22, Cadet West’s father, William L. West, writing from Madison, Georgia, granted permission for his son to resign. Cadet West resigned three days later.

Before West’s resignation made its way to the secretary of war’s desk, the superintendant at West Point pointed out that the name of J. A. West appeared in a newspaper amongst a list of officers appointed by the governor of Georgia to man the first two regiments from that state. However, the superintendant could not determine if the John A. West at the academy was the same person being appointed a second lieutenant in one of the Georgia regiments. “In this case I find the name of J.A. West, as having been appointed a Second Lieutenant by the Governor of Georgia. I have no means to ascertaining Cadet J. A. West to be the same person and only recommend the acceptance of his resignation.” The name appeared on a list in the U.S. Herald dated February 24 (referenced as from the “Federal Union Extra”). His resignation was accepted by the secretary of war on March 7, 1861.

Brig. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, U.S. Army

Joseph E. Johnston was born on February 3, 1807, near Farmville, Virginia. He was a classmate of Robert E. Lee at West Point, before graduating in 1829. He was commissioned in the U.S. Army and served in the Seminole and Mexican Wars and rose through the ranks until being appointed quartermaster general with the rank of brigadier general on June 28, 1860.

Like many U.S. Army officers from the state of Virginia, Johnston did not offer his resignation until after his native state voted to secede from the Union on April 17, 1861. Johnston resigned five days later, on April 22. “With feelings of deep regret, I respectfully tender the resignation of my commission in the Army of the United States.” He does not provide a reason for his resignation other than to state, “The feelings which impel me to this act are, I believe, understood by the Hon. Secretary of War.”

The following month, Johnston was commissioned a brigadier general in the regular army of the Confederacy and placed in charge of Harpers Ferry. He was instrumental in the battle of First Manassas, and his performance led to promotion to full general on August 31, 1861, and command of the Army of Northern Virginia. He would hold this command until he was wounded during the Peninsula Campaign at the Battle of Seven Pines on May 31, 1862, Robert E. Lee then assumed that command.

After recuperating from his wounds, he returned to the Confederate army, where he held a variety of departmental and army commands for the remainder of the war. He surrendered his Army of Tennessee on April 26, 1865, in Greensboro, North Carolina.

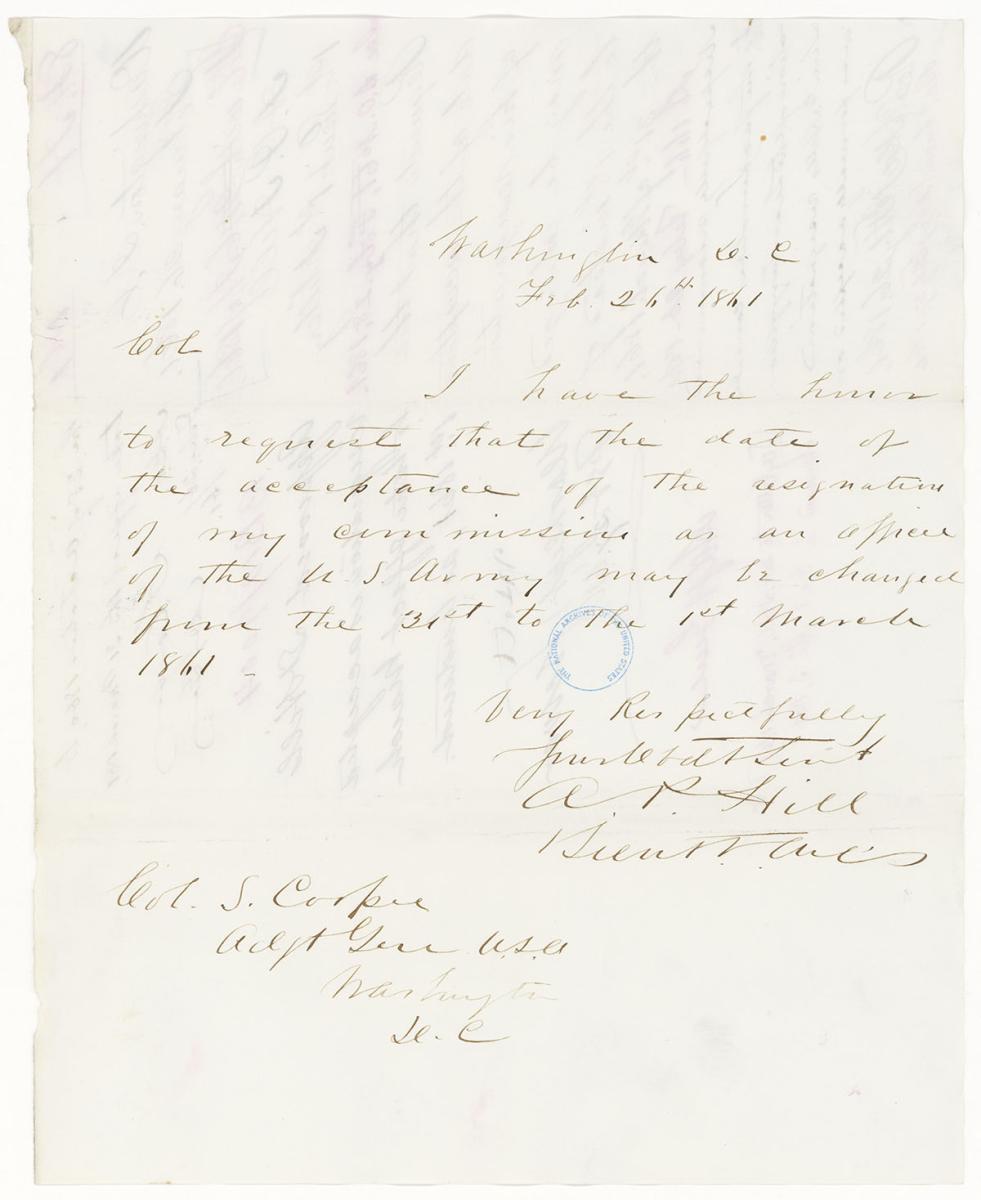

First Lt. Ambrose Powell Hill, U.S. Army

Ambrose Powell Hill was born in Culpeper, Virginia, on November 9, 1825. He graduated from West Point in 1847 and served in the First U.S. Artillery.

Unlike many officers who hailed from Virginia, Hill chose to resign his commission before the state voted to secede from the Union in April. Writing to the adjutant general from Washington, D.C., on February 26, 1861, Hill wrote, “I have the honor to request that the date of the acceptance of the resignation of my commission as an officer in the U.S. Army may be changed from the 31st to the 1st March 1861.” Back in the early part of October 1860, Hill requested a six-month leave of absence along with permission to resign his commission at the expiration of his leave. Hill took offense to the response from the adjutant general concerning his request. The adjutant general wanted a resignation showing the effective date immediately, presumably believing Hill was trying to do both in his initial correspondence. Hill was hurt, for he planned on submitting a separate resignation letter at the end of his leave. In his response to the adjutant dated October 12, 1860, Hill stated “[I] hereby tender the resignation of my commission as a First Lieutenant in the 1st Regt. of Artillery, United States Army, to take effect on the 31st day of March 1861.” Later in the letter he states, “I must again repeat that I have been deeply wounded by this unusual course upon the part of the Dept, as I do not feel conscious of having deserved it.”

Hill soon joined the Confederacy as colonel of the 13th Virginia Infantry. He was appointed brigadier general on February 26, 1862, and after a strong performance during the Peninsula Campaign, was promoted to major general in May of 1862. After conflicts arose between him and his commanding officer, Maj. Gen. James Longstreet, Hill was placed under Stonewall Jackson’s command. His troops soon became known as the “Light Division,” serving ably at Cedar Mountain and saving the day for Lee’s army at Sharpsburg. After the mortal wounding of Stonewall Jackson at Chancellorsville, Hill temporarily took over command of the corps before being wounded and passing the command on to J.E.B. Stuart. He was promoted to lieutenant general from May 24, 1863, and placed in charge of the Army of Northern Virginia’s newly formed Third Corps. He led his corps at the battle of Gettysburg and during the overland campaign the following year. He spent the remainder of 1864 and the spring of 1865 with Lee’s army in the lines of Petersburg, where he was killed by a Union straggler on April 2, 1865.

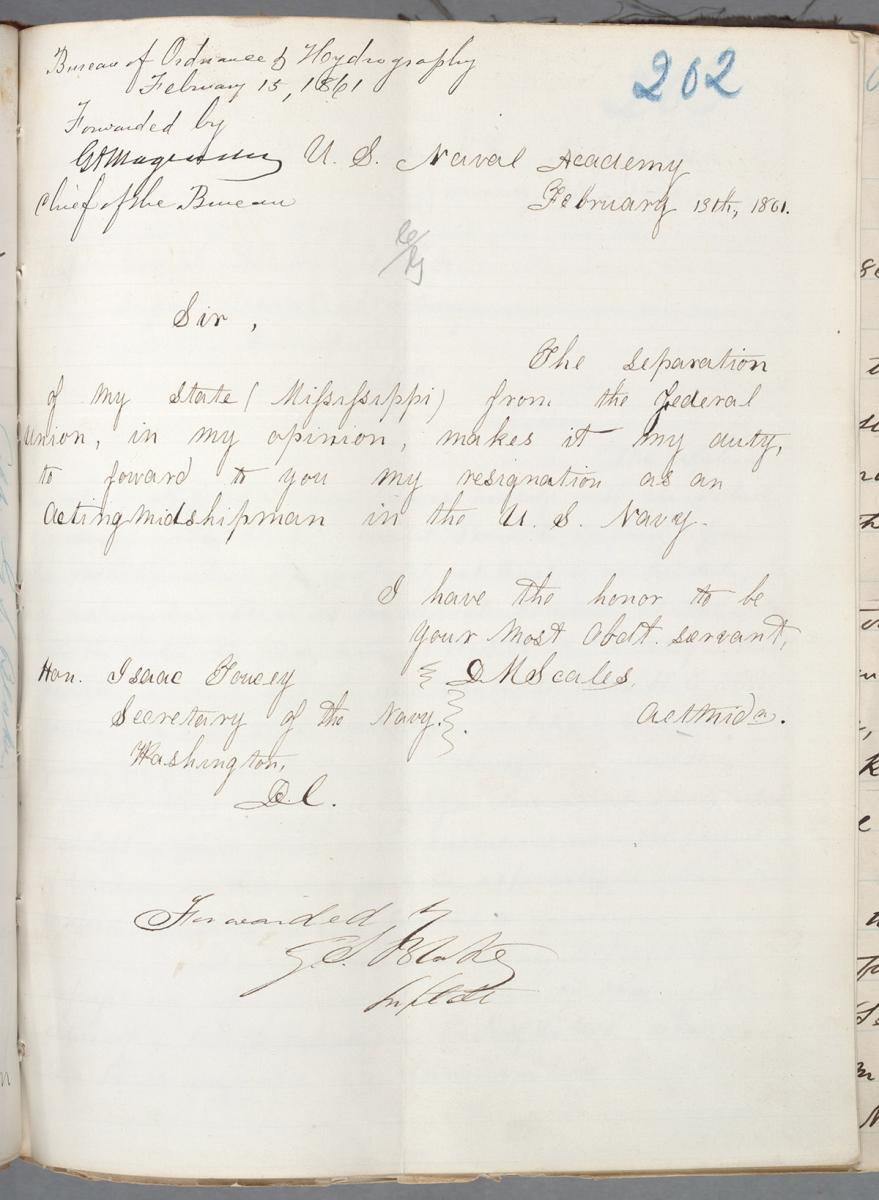

Acting Midshipman Dabney M. Scales, U.S. Naval Academy

With secession looming in early 1861, Southern parents started contacting their sons at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis. As each state seceded, the demand for their sons to resign increased. While some left the decision squarely in their sons’ hands, others expressed their wishes in no uncertain terms. Because midshipmen needed a parent or guardian’s permission to resign, many of these communications were submitted along with their resignations.

One father, communicating directly to the superintendant from Marshall County, Mississippi, wrote on January 28, 1861, “The relation in which Mississippi now places herself with the Federal Government of the U.S. would seem to impose upon her executive chief the propriety at least, if not his duty, of asking her sons at the Naval Academy at Annapolis and the cadets she may have at West Point to resign their positions in each school and return to their State allegiance . . . therefore give my son Dabney M. Scales my consent that he should resign immediately. . . . And may God, and His goodness, Wisdom & Mercy, so govern the destiny of my boy, that he may never have cause to regret his allegiance to the Stars & Stripes now severed by the secession of his State.” His son submitted his resignation on February 13, 1861, stating, “The separation of my state [Mississippi] from the Federal Union, in my opinion, makes it my duty, to forward to you my resignation as an acting midshipman in the U.S. Navy.”

Capt. George E. Pickett, U.S. Army

George E. Pickett was born in Richmond, Virginia, on January 28, 1825. He graduated last in his class from West Point in 1846. He was commissioned in the U.S. Army and served in several infantry regiments. He was cited twice for gallantry in the Mexican War and was later promoted to captain. He served in Texas and in Washington Territory, where he gained some notoriety for his part in the “Pig War” of 1859 involving the British and San Juan Island.

Writing to the adjutant general from Camp Pickett, San Juan Island, Washington Territory, on June 20, 1861, Pickett stated, “I have the honor to transmit through the [Head Quarters] of the Dept. of the Pacific my Resignation as a Captain in the 9th Infy.”

Pickett entered the Confederate army as a colonel. By the fall of 1862, he had risen to the rank of major general and was in command of a division in the Army of Northern Virginia. He participated in the battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia, and is most well known for the charge at Gettysburg that bears his name. The charge took place the third day of the battle, on July 3, 1863, in which his division took part in the large assault on the Union front.

Pickett went on to various commands and by war’s end was put in charge of the Confederate right flank at Petersburg, Virginia. Pickett failed to hold the flank when a larger force of Union cavalry and infantry attacked his position at Five Forks on April 1, 1865. Pickett was at a shad bake with other Confederate officers when the attack began. Robert E. Lee relieved Pickett of his command during the retreat toward Appomattox.

Capt. J.E.B. Stuart, U.S. Army

James Ewell Brown Stuart was born in Patrick County, Virginia, on February 6, 1833, and graduated from West Point in 1854. He served in the First U.S. Cavalry and was with Robert E. Lee at the capture of John Brown at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in October of 1859. He quickly rose through the ranks and was promoted to captain on April 22, 1861. Ironically, this last promotion was made possible by the departure of several Army officers above him who had resigned to join the Confederacy.

The state of Virginia voted to secede from the Union in April. The following month, Stuart wrote from Cairo, Illinois, to the adjutant general on May 3, 1861: “From a sense of duty to my native state (Va), I hereby resign my position as an officer in the Army of the United States.”

He soon joined the Confederacy as colonel of the First Virginia Cavalry. He fought in the battle of First Manassas and was later promoted to brigadier general. During the Peninsula Campaign the following year, Lee ordered a reconnaissance of McClellan’s right flank. Stuart proceeded to ride entirely around McClellan’s entire army, a feat that gained him much attention and fame. Stuart, a daring cavalry commander, was soon promoted to major general and served as the commander of the Cavalry Division, and later Cavalry Corps, of the Army of Northern Virginia. Besides his daring raids and ride around McClellan, Stuart is most known for his failure to provide Robert E. Lee proper intelligence during the Gettysburg campaign in 1863. He arrived at Gettysburg after the battle had already commenced. The following year, he was mortally wounded at Yellow Tavern on May 11, 1864, while confronting Sheridan’s cavalry force outside Richmond. He died the following day.

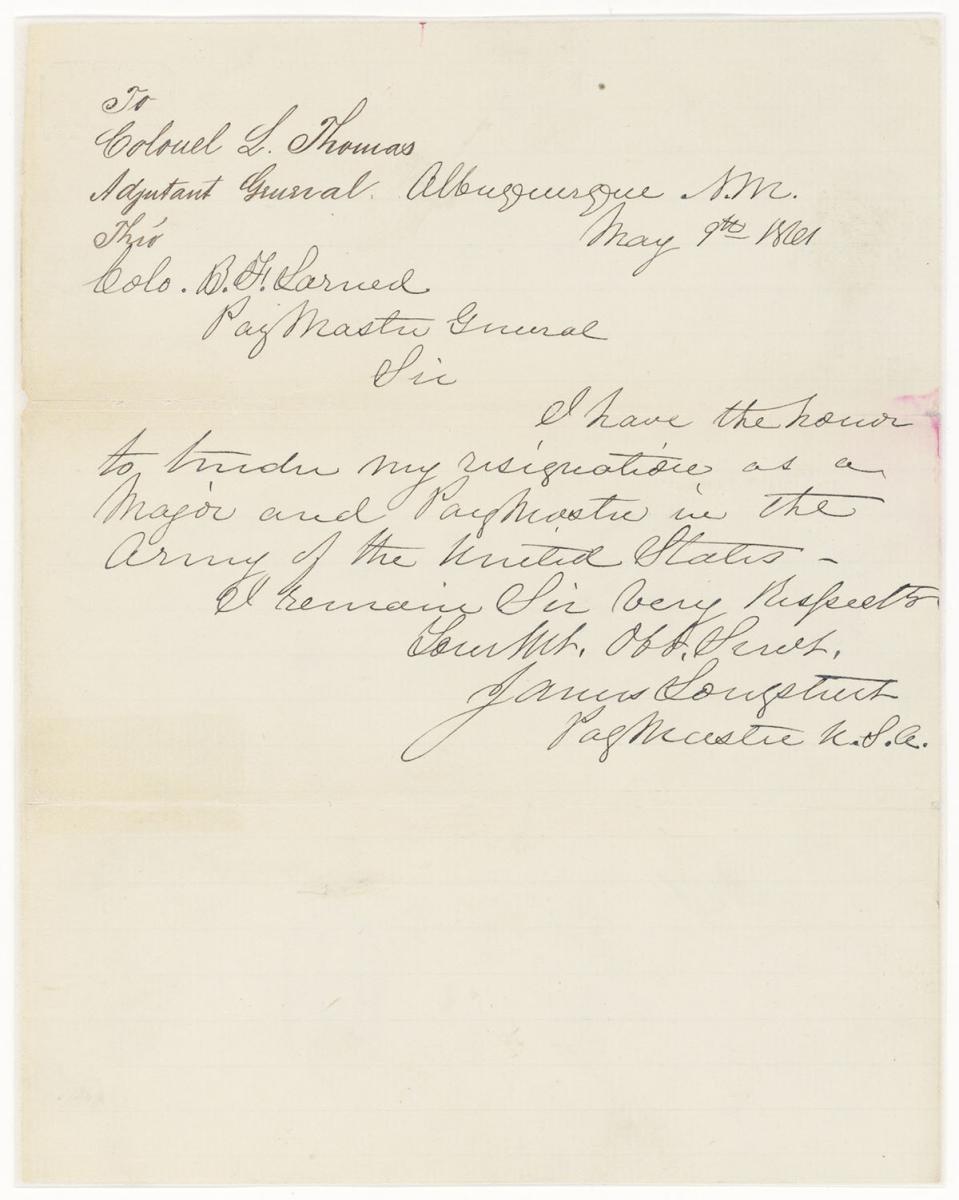

Maj. James Longstreet, U.S. Army

James Longstreet was born in South Carolina on January 8, 1821. He graduated from West Point in 1842 and served in the Indian campaigns and the war with Mexico. He rose through the ranks, and at the time of his resignation in 1861, he was a major and paymaster.

Writing to the paymaster general from Albuquerque, New Mexico, on May 9, 1861, Longstreet simply states, “I have the honor to tender my resignation as a Major and Paymaster in the Army of the United States.” Longstreet’s resignation was received in the adjutant general’s office on June 1 and was accepted the same day.

He was appointed a brigadier general in the Confederate army on June 17, 1861. He was promoted to the rank of major general on October 7, 1861, and to lieutenant general on October 9, 1862. He served in the eastern theater and participated in First Manassas, the Peninsula Campaign, and the battles of Second Manassas, Sharpsburg, Fredericksburg, and Gettysburg. He then went west to participate in the Battle of Chickamauga in September of 1863. He returned to the eastern theater in time to participate in the Battle of the Wilderness, where he was wounded on May 6, 1864. He was part of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia that surrendered at Appomattox Court House, April 9, 1865. Robert E. Lee referred to his capable corps commander as “my old war horse.”

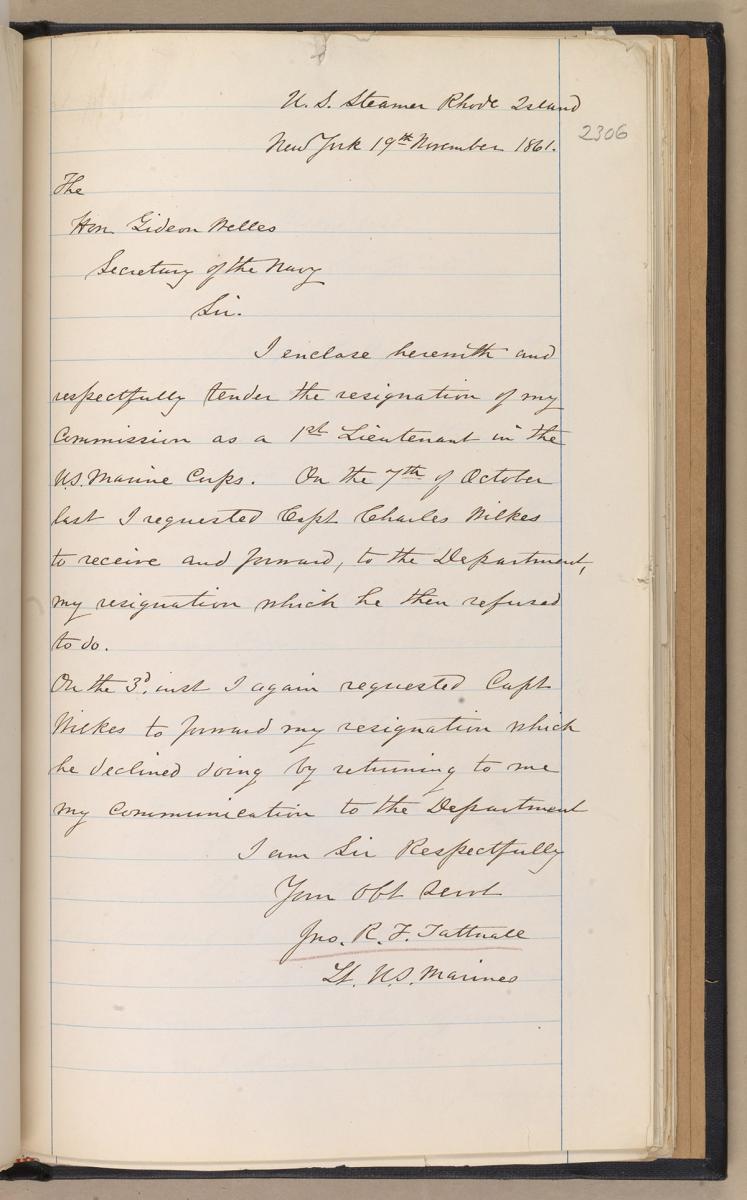

First Lt. John R.F. Tattnall, USMC

John Rogers Fenwick Tattnall, the son of Flag Officer Josiah Tattnall, was born in 1829. He was commissioned a second lieutenant, U.S. Marine Corps, on November 3, 1847, and was promoted to first lieutenant on February 22, 1857.

At the start of the Civil War, Tattnall was serving with the African Squadron on board the San Jacinto. He submitted his resignation to Capt. Charles Wilkes on October 7, 1861, requesting the commanding officer of the vessel to receive it and forward to the Navy Department. Wilkes refused. He tried again on November 3, and Wilkes again refused.

On November 19, in a letter addressed to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, he summed up his attempts to resign. On November 22, 1861, Welles handled the matter quickly, in a letter to the commandant of the New York Navy Yard: “transmitted herewith is the dismissal of First Lieutenant J.R.F. Tatnall, U.S. Marine Corps. You will send this officer under a guard, to Fort Warren in the Harbor of Boston there to be delivered to the Commandant of that Post, as a Prisoner.”

On November 27, 1861, Tattnall was sent to Fort Warren as a prisoner. He was exchanged on January 10, 1862, and released from Fort Warren on January 13, 1862. He was then commissioned as a captain in the C.S. Marine Corps later that month. He served at various times during the war in the Confederate Provisional Army and an Alabama infantry regiment before returning to the C.S. Marine Corps. He organized Company E of the Marine Corps, and his company was later surrendered on April 28, 1865, at Greensboro, North Carolina, as part of Gen. Joseph E. Johnston’s command.

Trevor K. Plante is a reference archivist in the textual archives services Division at the National Archives and Records Administration who specializes in 19th- and early 20th-century military records. He is an active lecturer at the National Archives and a frequent contributor to Prologue.

PDF files require the free Adobe Reader.

More information on Adobe Acrobat PDF files is available on our Accessibility page.