Out of War, a New Nation

Spring 2010, Vol. 42, No. 1

By James M. McPherson

The Civil War had a greater impact on American society and the polity than any other event in the country’s history.

It was also the most traumatic experience endured by any generation of Americans.

At least 620,000 soldiers lost their lives in the war, 2 percent of the American population in 1861. If the same percentage of Americans were to be killed in a war fought today, the number of American war dead would exceed 6 million. The number of casualties suffered in a single day at the battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, was four times the number of Americans killed and wounded at the Normandy beaches on D day, June 6, 1944. More Americans were killed in action that September day near Sharpsburg, Maryland, than died in combat in all the other wars fought by the United States in the 19th century combined.

How could such a conflict happen?

Why did Americans fight each other with a ferocity unmatched in the Western world during the century between the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 and the beginning of World War I in 1914?

The origins of the American Civil War lay in the outcome of another war fought 15 years earlier: the Mexican-American War. The question whether slavery could expand into the 700,000 square miles of former Mexican territory acquired by the United States in 1848 polarized Americans and embittered political debate for the next dozen years.

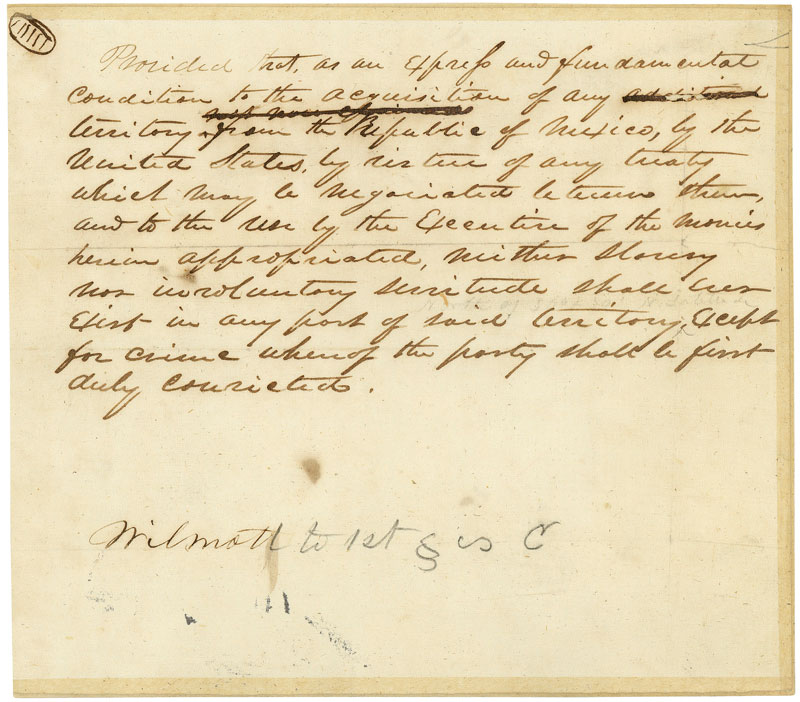

In the House of Representatives, northern congressmen pushed through the Wilmot Proviso specifying that slavery should be excluded in all territories won from Mexico. In the Senate, southern strength defeated this proviso. South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun introduced instead a series of resolutions affirming that slaveholders had the constitutional right to take their slave property into any United States territory they wished.

These opposing views set the terms of conflict for the next decade. When 80,000 Forty-Niners poured into California after the discovery of gold there in 1848, they organized a state government and petitioned Congress for admission to the Union as the 31st state. Because California’s new constitution banned slavery, this request met fierce resistance from southerners. They uttered threats of secession if they were denied their "right’ to take slaves into California and the other territories acquired from Mexico. The controversy in Congress grew so heated that Senator Henry S. Foote of Mississippi flourished a loaded revolver during a debate, and his colleague Jefferson Davis challenged an Illinois congressman to a duel. In 1850 the nation seemed held together by a thread, with war between free and slave states an alarming possibility.

Cooler heads finally prevailed, however. The Compromise of 1850 averted a violent confrontation. This series of laws admitted California as a free state, divided the remainder of the Mexican cession into the territories of New Mexico and Utah, and left to their residents the question whether or not they would have slavery. (Both territories did legalize slavery, but few slaves were taken there.) At the same time, Congress abolished the slave trade in the District of Columbia, ending the shameful practice of buying and selling human beings in the shadow of the Capitol.

But the Compromise of 1850 compensated the South with a tough new fugitive slave law that empowered Federal marshals, backed by the Army if necessary, to recover slaves who had escaped into free states.

These measures postponed but did not prevent a final showdown. The fugitive slave law angered many northerners who were compelled to watch black people—some of whom had lived in their communities for years—returned in chains to slavery. Southern anxiety grew as settlers poured into northern territories that were sure to join the Union as free states, thereby tipping the sectional balance of power against the South in Congress and the Electoral College.

In an effort to bring more slave states into the Union, southerners agitated for the purchase of Cuba from Spain and the acquisition of additional territory in Central America. Private armies of "filibusters," composed mainly of southerners, even tried to invade Cuba and Nicaragua to overthrow their governments and bring these regions into the United States as slave states.

The events that did most to divide North and South were the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 and the subsequent guerrilla war between pro- and anti-slavery partisans in Kansas territory. The region that became the territories of Kansas and Nebraska was part of the Louisiana Purchase, acquired by the United States from France in 1803. In 1820 the Missouri Compromise had divided this region at latitude 36° 30', with slavery permitted south of that line and prohibited north of it.

Considered by northerners to be an inviolable compact, the Missouri Compromise had lasted 34 years. But in 1854 southerners broke it by forcing Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, chairman of the Senate Committee on Territories, to agree to the repeal of the ban on slavery north of 36° 30' as the price of southern support for the formal organization of Kansas and Nebraska territories.

Douglas anticipated that his capitulation to southern pressure would "raise a hell of a storm" in the North. The storm was so powerful that it swept away many northern Democrats and gave rise to the Republican party, which pledged to keep slavery out of Kansas and all other territories.

An eloquent leader of this new party was an Illinois lawyer named Abraham Lincoln, who believed that "there can be no moral right in the enslaving of one man by another." Lincoln and other Republicans recognized that the United States Constitution protected slavery in the states where it already existed. But they intended to prevent its further expansion as the first step toward bringing it eventually to an end.

The United States, said Lincoln at the beginning of his famous campaign against Douglas in 1858 for election to the Senate, was a house divided between slavery and freedom. "'A house divided against itself cannot stand,'" he declared. "I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free." By preventing the further expansion of slavery, Lincoln hoped to "place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction."

Lincoln lost the senatorial election in 1858. But two years later, running against a Democratic party split into northern and southern factions, Lincoln won the presidency by carrying every northern state. It was the first time in more than a generation that the South had lost effective control of the national government. Southerners saw the handwriting on the wall. A growing majority of the American population lived in free states. Pro-slavery forces had little prospect of winning any future national elections. The prospects for long-term survival of slavery appeared dim. To forestall anticipated antislavery actions by the incoming Lincoln administration, seven slave states seceded during the winter of 1860–1861.

Before Lincoln took office on March 4, 1861, delegates from those seven states had met at Montgomery, Alabama, adopted a Constitution for the Confederate States of America, and formed a new government with Jefferson Davis as president.

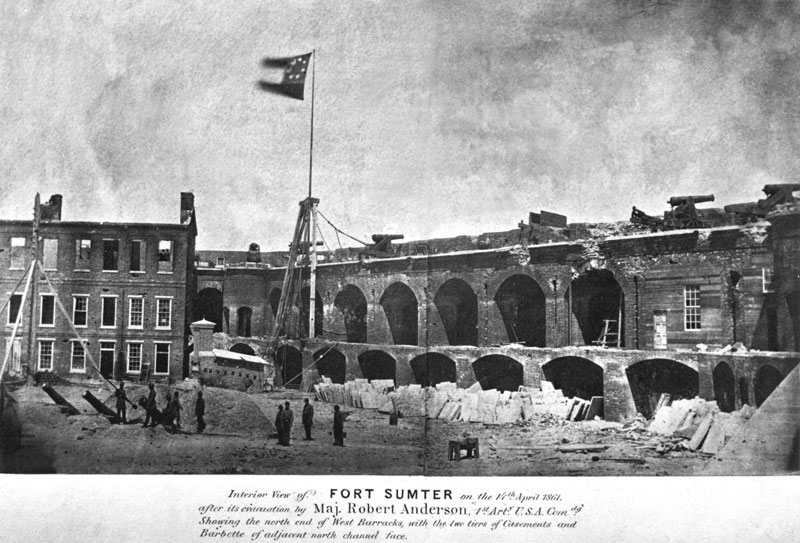

As they seceded, these states seized most forts, arsenals, and other Federal property within their borders—with the significant exception of Fort Sumter in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina.

When Lincoln took his oath to "preserve, protect, and defend" the United States and its Constitution, the "united" states had already ceased to exist. When Confederate militia fired on Fort Sumter six weeks later, thereby inaugurating civil war, four more slave states seceded.

Secession and war transformed the immediate issue of the long sectional conflict from the future of slavery to the survival of the Union itself. Lincoln and most of the northern people refused to accept the constitutional legitimacy of secession. "The central idea pervading this struggle," Lincoln declared in May 1861, "is the necessity that is upon us, of proving that popular government is not an absurdity. We must settle this question now, whether in a free government the minority have the right to break up the government whenever they choose." Four years later, looking back over the bloody chasm of war, Lincoln said in his second inaugural address that one side in the controversy of 1861 "would make war rather than let the nation survive; the other would accept war rather than let it perish. And the war came."

The articles that follow focus on key aspects of the four-year conflict that not only preserved the nation, but also transformed it. The old decentralized republic in which the federal government had few direct contacts with the average citizen except through the post office became a nation that taxed people directly, created an internal revenue bureau to collect the taxes, drafted men into the Army, increased the powers of federal courts, created a national currency and a national banking system, and confiscated 3 billion dollars of personal property by emancipating the 4 million slaves. Eleven of the first 12 amendments to the Constitution had limited the powers of the national government; six of the next seven, beginning with the 13th amendment in 1865, vastly increased national powers at the expense of the states.

The first three of these postwar amendments accomplished the most radical and rapid social and political change in American history: the abolition of slavery (13th) and the granting of equal citizenship (14th) and voting rights (15th) to former slaves, all within a period of five years. This transformation of more than 4 million slaves into citizens with equal rights became the central issue of the troubled 12-year Reconstruction period after the Civil War, during which the promise of equal rights was fulfilled for a brief time and then largely abandoned.

During the past half century, however, the promises of the 1860s have been revived by the civil rights movement, which reached a milestone in 2008 with the election of an African American President who took the oath of office with his hand on the same Bible that Abraham Lincoln used for that purpose in 1861.

The Civil War tipped the sectional balance of power in favor of the North. From the adoption of the Constitution in 1789 until 1861, slaveholders from states that joined the Confederacy had served as Presidents of the United States during 49 of the 72 years—more than two-thirds of the time. Twenty-three of the 36 Speakers of the House and 24 of the presidents pro tem of the Senate had been southerners. The Supreme Court always had a southern majority before the Civil War; 20 of the 35 justices down to 1861 had been appointed from slave states.

After the war, a century passed before a resident of an ex-Confederate state was elected President. For half a century only one of the Speakers of the House and no president pro tem of the Senate came from the South, and only 5 of the 26 Supreme Court justices named during that half century were southerners.

The United States went to war in 1861 to preserve the Union; it emerged from the war in 1865 having created a nation. Before 1861 the two words "United States" were generally used as a plural noun: "the United States are a republic." After 1865 the United States became a singular noun. The loose union of states became a single nation. Lincoln’s wartime speeches marked this transition. In his first inaugural address he mentioned the "Union" 20 times but the "nation" not once. In his first message to Congress on July 4, 1861, Lincoln used the word Union 32 times and nation only three times. But in his Gettysburg Address in November 1863 he did not mention the Union at all, but spoke of the nation five times to invoke a new birth of freedom and nationhood.

The Civil War resolved two fundamental, festering problems left unresolved by the American Revolution and the Constitution.

The first was the question whether this new republic born in a world of kings, emperors, tyrants, and oligarchs could survive. The republican experiment launched in 1776 was a fragile entity. The Founding Fathers were fearful about prospects for its survival. They were painfully aware that most republics through history had been overthrown by revolutions or had collapsed into anarchy or dictatorship. Some Americans alive in 1860 had twice seen French republics succumb to the forces of reaction. The same fate, they feared, could await them. That was why Lincoln at Gettysburg described the war as the great "testing" whether a "government of the people, by the people, for the people" would survive or "perish from the earth." It did not perish. Northern victory preserved the nation created in 1776. Since 1865 no disaffected state or region has seriously tried to secede. That question appears to have been settled.

At Gettysburg, Lincoln spoke also of a "new birth of freedom." He was referring to the other problem left unresolved by the Revolution of 1776—slavery. The Civil War settled that issue as well. Antebellum Americans had been fond of boasting that their "land of liberty" was a "beacon light of freedom" to the oppressed peoples of other lands. But as Lincoln had put it in 1854, "the monstrous injustice" of slavery deprived "our republican example of its just influence in the world—enables the enemies of free institutions, with plausibility, to taunt us as hypocrites." With the 13th amendment, that monstrous injustice, at least, came to an end.

Before 1861 two socioeconomic and cultural systems had competed for dominance within the body politic of the United States: an agricultural society based on slavery versus an entrepreneurial capitalist society based on free labor. Although in retrospect the triumph of free-labor capitalism seems to have been inevitable, that was by no means clear for most of the antebellum era.

Not only did the institutions and ideology of the rural, agricultural, plantation South with its rigorous system of racial caste and slave labor dominate the United States government during most of that time, but the territory of the slave states also considerably exceeded that of the free states and the southern drive for further territorial expansion seemed more aggressive than that of the North. It is quite possible that if the Confederacy had prevailed in the 1860s, the United States might never have emerged as the world's largest economy and foremost democracy by the late 19th century.

The institutions and ideology of a plantation society and a slave system that had dominated half of the country before 1861 went down with a great crash in 1865 and were replaced by the institutions and ideology of free-labor entrepreneurial capitalism. For better or worse, the flames of the Civil War forged the framework of modern America.

Mark Twain remarked on this process in 1873. The "cataclysm" of the Civil War, he wrote, "uprooted institutions that were centuries old, changed the politics of a people, and wrought so profoundly upon the entire national character that the influence cannot be measured short of two or three generations." Five generations have passed, and we are still measuring the consequences of that cataclysm.

James M. McPherson, professor emeritus of history at Princeton University, is one of the nation's foremost Civil War historians. His book Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era won the Pulitzer Prize for history in 1989. Two other Civil War–related books, For Cause and Comrades and Tried by War, have won the prestigious Lincoln Prize. In 2008, McPherson received the Records of Achievement Award from the Foundation for the National Archives.