An Alleged Wife

One Immigrant in the Chinese Exclusion Era

Spring 2004, Vol. 36, No. 1

By Robert Barde

© 2004 by Robert Barde

Chew Hoy Quong and his "alleged wife," Quok Shee, crossed my path quite by accident, two among thousands of Chinese would-be immigrants who had tried to enter the United States in 1916. Their experience was one of hardship, tenacity, and sadness. It was unusual, and it was puzzling, for through it runs a thread of mystery.

Their story begins in the thirty-fourth year of the Chinese Exclusion Act. It is a tale now more than eighty years old. Today it seems dramatic; back then it surely passed unnoticed. No newspaper headlines, no memoirs. Only the public record remains, a folder of documents in which brief portions of their lives were written down, assembled, and preserved with bureaucratic thoroughness: Investigation Case File no. 15530/6-29 at the National Archives and Records Administration–Pacific Region (San Francisco) in San Bruno, California.

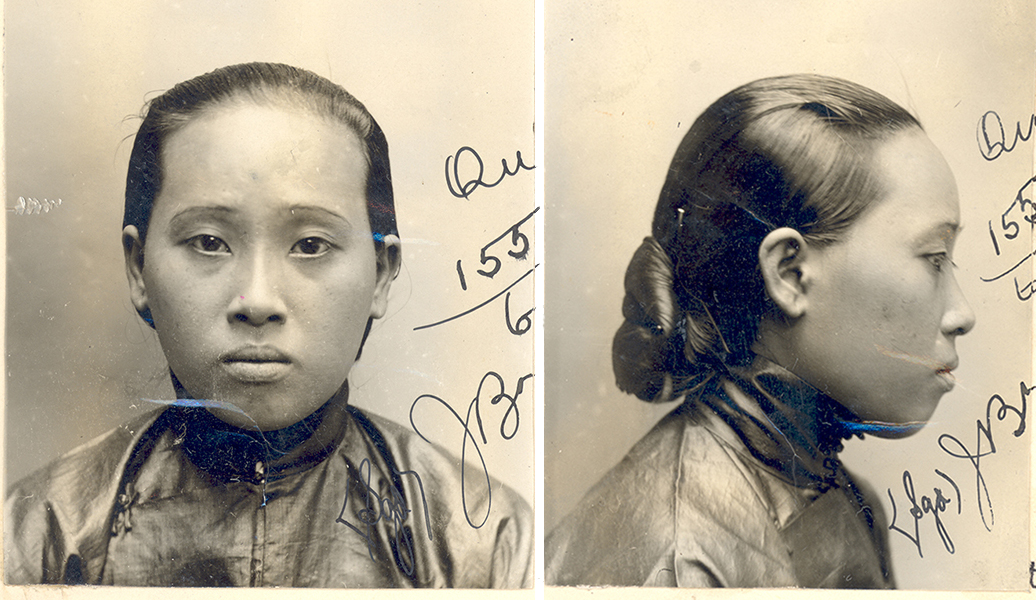

Quok Shee's "investigation case file" is more than an inch thick, begun in September 1916 and not closed until August 1918. That startled me, for it meant that for almost two years Quok Shee had been held in detention at the Angel Island Immigration Station. As I leafed through her file, the dry and dated pages jumped to life. She had been repeatedly interrogated, denied access to a lawyer, plagued by depression, subjected to smallpox, isolated from a husband she scarcely knew yet who was her only contact in America, pulled this way and that. One hundred and fifty pages of legalistic maneuvering, inquisitorial interrogations, medical evaluations, intrigue, and court orders—all over the attempt of one little Chinese woman to enter the United States.

Her case was not ordinary, but then neither were the times, the place, nor the other characters. Scandal was not a stranger to Angel Island, populated by a spectacular assortment of honest and dishonest immigrants, officials faithful or corrupt, an ambitious investigator-knight errant, smugglers, lawyers of every stripe, racists, and do-gooders. Such a setting, with its rancid undertone of moral ambiguity, was part and parcel of enforcement of the Chinese Exclusion Act and its equally racist successors.

Here is the story of Quok Shee and her "alleged husband" (as the Immigration Service always referred to him), Chew Hoy Quong—or at least the part we can document. The official record is stored safely in the National Archives: their testimony, the memorandums of immigration officials, and the lawyers' appeals. If we listen carefully, we can imagine their voices, sense the times, and feel the dramas that once swirled around Angel Island.

Coming to America

In 1916, entering the United States was relatively easy for most would-be immigrants. Only in 1875 had the federal government begun to regulate immigration, prohibiting the entry of members of "loathsome classes" as undesirable immigrants. By 1916 the list of undesirables had grown to include those with all sorts of physical or mental defects that might prevent one from earning a living, paupers and those likely to become a public charge, contract laborers, assisted aliens, criminals, prostitutes "or females for any immoral purpose," persons with contagious diseases, felons, polygamists, anarchists, and the illiterate. And those debarred under provisions of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

The Chinese were the only race of people to be singled out by the United States for special treatment through immigration legislation. The Chinese Exclusion Act of May 6, 1882, was intended to end the arrival of Chinese laborers into the United States and to bar Chinese from naturalization. Only certain classes of Chinese were even allowed to enter the United States. They included merchants, teachers, consular officials, tourists, and the wives and children of such exempt individuals. Chinese residing in the United States before 1882 were also allowed to leave and return. The act was initially effective for ten years, but it was renewed once and then, in 1904, made permanent. It was finally repealed in 1943.

How effective were the Chinese Exclusion Acts at excluding the Chinese? For the last half of the 1870s, immigration from China had averaged less than nine thousand a year. In 1881, nearly twelve thousand Chinese were admitted into the United States; a year later the number swelled to forty thousand. And then the gates swung shut. In 1884, only ten Chinese were officially allowed to enter this country. The next year, twenty-six.

By 1916 the numbers had inched upward; a total of 1,762 ethnic Chinese were officially admitted as immigrants, about average for the decade. Still, the Chinese population of the United States was shrinking. In 1880, it had been over 105,000; by 1916 it had dwindled to around 65,000.

Chew Hoy Quong had first come to California as Congress was debating the Chinese Exclusion Act. He arrived in San Francisco from Hong Kong in 1881 and immediately went to work in his uncle's store on Washington Street. When the uncle died in 1896, Chew inherited the business. Like many other merchants, he saw his store destroyed in the earthquake and fire of 1906. He told immigration authorities that he had run a company near Stockton until 1915, when he joined the Dr. Wong Him Company, a Chinatown firm dealing in herbs and medicines.

Having lived in the heart of the San Francisco Chinese community for nearly thirty years, Chew Hoy Quong probably knew the procedures for immigrating to the United States. He would have known that if Chinese merchants wanted to leave the country and re-enter, their firms were required to register with local authorities. The Dr. Wong Him Company had done so. On February 2, 1915, Chew joined the firm, investing a thousand dollars to buy out the share of one of the founding partners. As part owner of a legitimate business, he could now apply to the Immigration Service for a Form 431, which he did on March 25. When this was approved, he became entitled to leave the United States. More important, he became entitled to return—and to bring with him any wife or children he might have.

Carefully, Chew had laid the groundwork for the next, and perhaps last, big change in his life: to find a wife and get married. On May 15, 1915, at age fifty-five, he boarded the SS Manchuria for Hong Kong. He later testified that, using a go-between, he met a Hong Kong woman named Lee Shee who had a daughter whom she hoped to marry off: Quok Shee, age twenty.

Chew subsequently testified that on February 21, 1916, he and Quok Shee were married. We do not know when Chew told his bride that they would be going to Gan San ("Gold Mountain"—i.e., the United States). Perhaps her mother told her that the prospective husband resided in the United States. Or perhaps Quok Shee only found out after the wedding. But she had over five months to adjust and prepare for the future, five months during which she and Chew said they lived in rented space on the third floor of a Hong Kong building.

It was probably in June or July that Chew arranged for passage back to America on the Japanese ship Nippon Maru. Ship owners in the business of transporting immigrants clearly understood that should a passenger be turned back or delayed at the U.S. port of entry, the shipping line would incur additional costs—the immigrant's upkeep on Angel Island and, should the would-be immigrant be refused entry, the responsibility of transporting that person back to the country of origin.

Thus the Toyo Kisen Kaisha line, owner of the Nippon Maru, had an incentive to see that their passengers' documents—especially their evidence of good health—were in order. In Hong Kong, Quok Shee was taken to the TKK office, where she presented her photograph and obtained a certificate stating that she was free of hookworm and trachoma.

On August 3, 1916, the Nippon Maru sailed from Hong Kong, arriving in San Francisco on September 1. From the ship's passenger list, signed by Captain Nagano as required by American law, we know that she carried 188 passengers: 90 Japanese, 75 Chinese, and 23 others of various nationalities (mostly Europeans and Americans). Among the Chinese were Chew Hoy Quong and his wife of six months, Quok Shee. Quok Shee had crossed the Pacific, but in many ways her journey to America had just begun.

Arrival

For most non-Asian passengers, whether immigrants, returning citizens, or passengers in transit, passing through the port's health and immigration controls would have been done quickly. Visas were not necessary, and there were few formal requirements for entry. But for Chinese like Quok Shee and Chew Hoy Quong, the process was quite different. Along with the Nippon Maru's other Chinese passengers hoping to enter the United States, they were taken to Angel Island, several miles away in San Francisco Bay.

Perhaps 300,000 persons passed through the Angel Island Immigration Station between 1910 and 1940. For Chinese, it was the principal place of entry into the United States. Perhaps 75 percent of the Chinese entering through San Francisco were detained there for some period. Compared to the tens of millions who passed through Ellis Island in New York, Angel Island was a small operation. But it figures large in the history and folklore of immigration to California, a very visible reminder of the ordeals of those who passed through it, and of the country's determined efforts to keep them out.

As an outpost of the Immigration Service, Angel Island led a short and rather unhappy life. It had long been considered unsatisfactory by the time it was closed, following a fire, in 1940. From the beginning it was a source of dissatisfaction for both immigrants and immigration officials. The island was assigned the role of enforcing the grossly unfair Chinese Exclusion acts, and that this was done in a callous manner only compounded the injury and resentment. Firsthand testimony—some carved into the very walls—of former detainees speaks of injuries physical and emotional. Quok Shee and her husband were about to enter that labyrinth.

"Twenty Questions," Played for Keeps

The next day, September 2, J. P. Hickey, acting assistant surgeon of the U.S. Public Health Service, examined Quok Shee. He would have found her to be four feet, nine inches tall, able to read and write, and without a penny to her name. He signed her "Medical Certificate of Release." One hurdle had been cleared, but the couple was still held in the island's detention center.

On September 5 Quok Shee and her "alleged husband" were interrogated by the Chinese Division of the United States Immigration Service. The interrogation was an expected—and dreaded—part of the entry process for most Asians. The standard interrogation always contained a minimum of fifteen to twenty questions; Chew was asked more than one hundred.

Chinese immigrants complained bitterly about the interrogations, whose unnerving, inquisitorial style were liable to trip up even the most honest immigrant. Immigration inspectors were convinced that many of the Chinese trying to enter as children or wives of resident Chinese were, in fact, fraudulent. These suspicions were not unfounded; many entering males were "paper sons" (i.e., fictitious sons), and there probably was a trade in women being brought in for "immoral purposes." Chew Hoy Quong would certainly have been aware of the interrogation that loomed before them, and surely he and his wife used the long trip from Hong Kong to prepare for it.

There were two initial interrogations: one for Quok Shee and a separate one for Chew Hoy Quong. Both were conducted by Inspector J. B. Warner (through interpreters) and stenographer H. F. Hewitt. Quok Shee's case file contains the verbatim transcripts of both interviews.

Whereabouts in Hong Kong did you marry this woman?

C: Number 20 Wah Hing Street—west.

How was the bedroom lighted?

C: From a window in the hall.

Q: The bedroom was lighted from a window in front of the building.

How was the parlor lighted?

C: From a window facing the street.

Q: From a window in front of the building.

How was the parlor furnished?

C: One table, two chairs, one mantel clock; that is all.

Q: Clock and round table, 4 chairs, American, one cuspidor and looking glass.

Did you ever visit your home village after you married this woman?

C: Yes. I went home once.

Q: Yes. A number of times. I don't remember how many times.

How long did you remain?

C: Altogether six days, that is, including the time it took to go back and forth.

Q: 10 some odd days—a number of times.

Have you any children who you claim as yours?

C: My blood brother, Chew Kai Quong, gave one of his sons to me, who I adopted. I now, at this age, will probably have no children and therefore he gave me this boy to look after the ancestral service at home. . . . My brother brought him to Hong Kong to bid me good bye before I left for the United States.

Did he visit your home?

C: Yes.

How long did he remain there?

C: They stayed in the same building during his visit, on the second floor—Sun Chung Co.

Q: I don't know. They never mentioned it.

Are you positive this woman is your wife?

C: Yes.

You were married according to the Chinese custom?

C: I was married according to the Chinese new custom.

What is the Chinese new custom?

C: Chinese custom except there is no worshipping.

Are you positive you are not bringing this woman to the United States for an immoral purpose

C: Yes.

Inspector Warner must have entertained some doubts about their story. Later that same day, he and stenographer Hewitt recalled Chew for further questioning. He was "cautioned to be careful in his answers."

I want to know how many times you visited your village after your marriage

Only once.

Are you positive of that?

I am positive I only made one trip. . . .

Were you away from your village at any other time?

No.

Are you positive of that?

I was in Macao; a friend of mine invited me to a celebration there, for two days, on two different occasions.

Were those the only times you were ever away from your wife?

Yes.

Later that day, Inspector Warner made a favorable recommendation: he, at least, was convinced, and Quok Shee was on her way to being admitted to the United States. Or so it seemed.

More Questions

In fact, the Immigration Service did not release Quok Shee. Chew Hoy Quong was already a legal resident and free to enter the country, which he did on September 5. But something was amiss, and Quok Shee remained in detention on Angel Island. More ominously, the Immigration Service wanted to talk to Chew again.

On September 13, Chew took the 8:45 a.m. steamer from pier 7 back to Angel Island. He and his wife were again subjected to extensive questioning: 115 questions were put to Chew, 65 to his "alleged wife." As before, they were questioned separately and given no chance to talk to each other. This time, the interrogation was conducted by "Law Officer" W. H. Wilkinson. Again, only the stenographer and an interpreter were present. The same questions were asked again and again, each time in a slightly different way, brusquely jumping back and forth. The point was to catch them out and "prove" that they were not husband and wife.

This time, the interrogations explored how the "alleged husband's" story diverged from that of his "alleged wife." Wilkinson's questions focused on three areas: Quok Shee's knowledge of the furnishings and other occupants of the building they inhabited in Hong Kong, Chew's visit(s) to his native village, and the matter of getting onto the ship in Hong Kong. For example:

What kind of a clock did you have in your parlor?

C: We had a metal case clock on the table in the parlor (indicates about six inches square).

Q: It was a large clock hanging on the wall . . . in the parlor. . . . Wooden.

Wilkinson was more than skeptical. After the interrogations, he wrote a "Memorandum for the Commissioner." In it, he emphasized the following discrepancies, in addition to the number of visits made by the alleged husband to his home village:

- The husband and wife disagreed on the nature and number of occupants on the second floor of their Hong Kong building.

- The husband said that their apartment on the third floor was on the top floor, while the wife stated that there were people living above her.

- The husband testified that the apartment had a metal clock, while the wife said it was made of wood.

- Chew's adopted son lived on the ground floor during his visit, but the wife never saw him.

- The husband and wife disagreed about the number of men accompanying them from the house to the steamer (SS Nippon Maru).

Wilkinson's conclusions were brief but brutal: "In view of the fact that the above contradictory statements appear incompatible with the relationship claimed, I recommend that the applicant be denied admission."

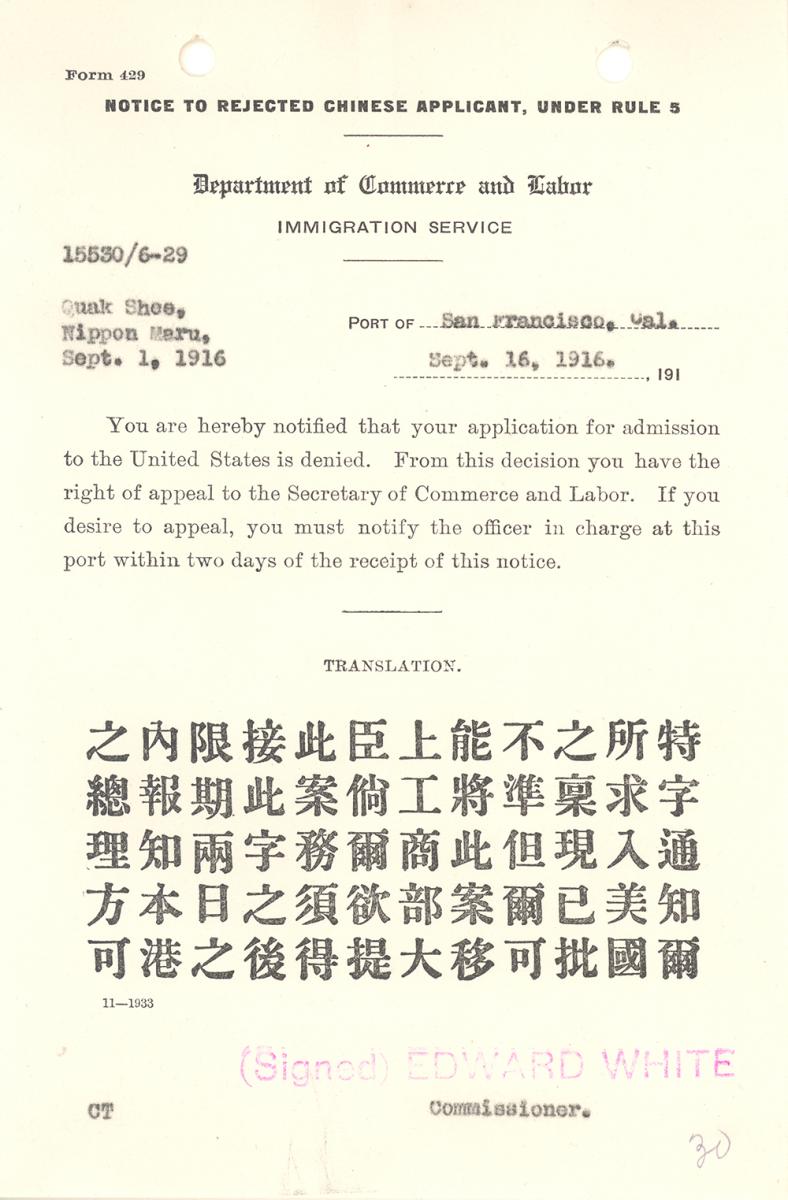

Charles Meehan, inspector-in-charge of the Immigration Service's Chinese Division, immediately informed Quok Shee that she had been refused admission: a form letter was drawn up and read to her through interpreter Chin Jack. The next day, Commissioner White wrote to both Quok Shee and the Chinese consul general, informing them that her application to land had been denied. The brisk "Notice to Rejected Chinese Applicant, Under Rule 5" was thoughtfully printed in both English and Chinese. Quok Shee was advised that she had two days to launch an appeal.

Two days for a poor immigrant to get a lawyer? Who would take such a case? Had she known what lay in store for her, she might have resisted engaging one. She surely had no idea how long and how tortuous her struggle would be.

Enter the Lawyers

Quok Shee's being denied admission was a setback, but Chew Hoy Quong was not unprepared. As soon as he sensed that something was amiss—probably when he was called back for further questioning—he immediately engaged the services of the San Francisco legal firm of McGowan and Worley, well known as specialists in the problems of Chinese immigrants. There was also a whiff of the less-than-respectable about them. Alexander Worley had frequent run-ins with the Immigration Service and with the courts, and neither he nor George McGowan was shy about taking on unpopular cases.

These were competent lawyers, and it was not at all unusual for them to be defending Chinese clients. The Chinese in California had a long history of using American lawyers and the American legal process to fight the Chinese Exclusion Act and its various successors, as well as discriminatory local ordinances. They also launched many legal actions against specific instances of unfair application of the exclusion laws. In the first ten years of the Exclusion Acts, more than 7,000 legal appeals were filed by Chinese, and between 1891 and 1905, an additional 2,600. There was plenty of work, and no shortage of able and willing white lawyers to earn the fees.

McGowan took charge of Quok Shee's case and went right to work. On September 11, acting on behalf of Chew as the "alleged husband," he requested Quok Shee's records, including the report of the examining inspector and the review of the law officer. These, however, were withheld by the Immigration Service because "said report does not contain any evidence whatsoever." Eventually, this refusal would be used against the government, but its initial effect was to keep Quok Shee on Angel Island.

McGowan and Chew kept testing the government's resolve to exclude Quok Shee. On September 22 they filed a sworn affidavit in which Chew states his background as a law-abiding citizen, provides details on his marriage to Quok Shee and their stay in Hong Kong, and shows how discrepancies in their interrogation testimony could be easily explained.

The affidavit was forwarded to Commissioner White on September 23, along with two other documents: a request to interview Quok Shee and a nine-page "Application to Re-open Case: Misunderstanding of purport of questions propounded and mistake of effect of Chinese customs bearing upon competency and relevancy of certain inconsistencies on the face of the record."

McGowan tried to use to his clients' advantage existing notions of how alien and incomprehensible were the ways of the Chinese. He quoted at length from Things Chinese, a book first published in 1892, to demonstrate how Chinese customs are different from "civilized" ones, especially those that concern the status and treatment of women. In trying to explain discrepancies in their testimony, Quok Shee's lawyer argued that Chinese women were sheltered, uneducated, unworldly, and basically, incompetent: "Matters of this kind only go to show that too much has been expected in this examination of the testimony of this Chinese wife."

Commissioner White was not in the least persuaded. On September 26 he notified McGowan and Worley that their request to reopen the case was denied. Further, the request that Quok Shee be able to confer with her "alleged husband" and with her lawyer was also denied. The next day McGowan tried appealing to whatever sense of compassion the Immigration Service might have:

This applicant having been held incommunicado at your station since the 1st day of September, 1916, she having been kept separate, apart, and away from her husband during all of that time, the husband now desires to request that he be permitted to see, talk to, comfort and console his wife, who journeyed with him to this country on the same boat and to whom you have denied admission.

The Immigration Service was not in the compassion business. Permission was denied.

For McGowan and Worley, the next stage was to appeal to higher-ups in Washington: to the secretary of labor. On September 28, Commissioner White in San Francisco forwarded a copy of Quok Shee's file to Washington. In the dossier was all the Immigration Service's information on Quok Shee that had been shown to McGowan—and some that had not.

This administrative appeal, too, was rejected on November 21, 1916, when the secretary of labor ordered that Quok Shee be deported, "said deportation to take effect Saturday, the 25 day of November, 1916." It seemed that Quok Shee's attempt to enter the United States had failed and that, after three months in captivity on Angel Island, she would be forced to return to China.

Ordered Deported

Rather than accept defeat, Chew turned to the courts to free his wife. To do so, he somehow brought in additional legal firepower: Dion Holm, a young, brilliant lawyer whose family had been in business in San Francisco since the gold rush.

Holm resorted to a widely recognized remedy in the Anglo-American legal system for violations of personal liberty: the writ of habeas corpus. The most important version of this writ directs someone who holds another in custody to produce the body of that person before the court in order that the court may rule on the legality of the detention. In other words: "produce the body of the person you hold, and charge that person with a crime or release him." Or her.

Chinese in the United States had long experience with writs of habeas corpus, with their American lawyers using it from the inception of the Exclusion Act to prevent the Immigration Service from denying entry to Chinese women. According to Vincent Tang, those with the most success were the Chinese criminal gangs (tong) who brought in prostitutes. With ample financial resources to hire lawyers, file writs, appeal deportations, and "grease the wheels" where needed, tong members were able to secure the entry of many prostitutes. So many, in fact, that gaining entry via a writ of habeas corpus practically labeled a woman a prostitute. In 1890, Mrs. S. L. Baldwin complained that

Cargoes of such women are landed here without certificates while wives of respectable Chinese . . . cannot land. It is maddening to think of the writ of habeas corpus, that sacred birth right of Anglo Saxons, and the safeguard of our liberties, being turned into a slave chain to drag these women down to hell.

Petitioning the court for a writ of habeas corpus was thus a necessary last resort. On November 24, the day before Quok Shee was to be deported, Dion Holm went to the Federal District Court for Northern California on behalf of Chew and filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus.

Judge Dooling of the U.S. District Court was known for being more favorably disposed toward immigrants (and opposed to administrators denying immigrants "ordinary fairness") than most judges. He immediately issued a court order for the commissioner of immigration to appear on November 29. The delay was a brief one. On December 15 Judge Dooling ruled in favor of the government and denied the petition of a writ of habeas corpus. Four days later, Immigration Commissioner White issued another order regarding Quok Shee to the inspector in charge, Deportation and Detention Division, Angel Island Station: "You will see that she is deported on the next available steamer of the line that brought her unless this office is in the meantime served with an order of Court staying such deportation."

The last document for 1916 in Quok Shee's case file is lawyer Holm's letter of December 22 to the Immigration Service: "You were served with an Order staying all proceedings in this matter and also a Citation to show cause why the judgment in the case as rendered by the District Court should not be corrected. These two papers constitute sufficient notice to you to stay deportation." Quok Shee's case would now go to the court of appeals, and Quok Shee would remain on Angel Island.

The Long Wait

Compared with the speed with which administrative appeals had been acted upon, the progress of Quok Shee's court case was interminably slow. Not until August 1917 would the court of appeals rule on her case. In the meantime she remained in limbo—neither charged with any crime nor free to enter the United States—and in detention on Angel Island.

Many detainees have told of the lamentable conditions of incarceration on Angel Island, of their isolation and emotional exhaustion. Told to oral historians or written on the walls of the barracks, their words speak of a desolate period in their lives. For women, the effects of incarceration were even worse. Chinese women of that period were much more likely to be uneducated and less worldly than male detainees. Their social support networks, too, were weaker. Their numbers were perhaps but one-tenth that of the men, making it less likely that they would have the companionship of someone who spoke their own dialect. Quok Shee's fate was this, and more.

Early in 1917, smallpox broke out in the female quarters on Angel Island. Quok Shee was held for observation at the Public Health Service's quarantine station on the opposite side of the island, then released on March 20. One can only imagine how the threat of smallpox and subsequent removal to the station must have compounded her sense of isolation and despair.

Her desperation did not escape notice by the Immigration Service. Less than a week after being released from quarantine, Quok Shee was interviewed by Inspector Charles Mayer and badgered to drop her appeals:

Is it true that you want your case in the courts abandoned and that you desire to be deported on the "Sib. Maru" on April 3?

Yes.

Why do you want to go back and not wait for the court's decision in your case?

Well I don't know how long that is going to be and I have been here 7 months already.

Do you want to be landed in the U.S.?

Within this few days, if I can be landed, if not I will go back on the "Siberia."

Why do you want to go back on the "Siberia" rather than any other vessel?

Because I understand there are some others going on the same boat and I wanted to go.

If none of those others go back on the "Siberia" do you want to go on the "Siberia" anyway?

Yes.

At around the same time, an anonymous handwritten note on Department of Labor paper appears in her file:

Kwok Shee has had no money for seven months—is wearing shoes and stockings that have been given to her by American friends. She doesn't know what has been done about her case and desires earnestly to be sent back to China. She feels very much neglected because she is clinging to the idea that she is really married and gets no response either from her Chinese friends or her lawyer. She has sent word to her lawyer on an average of once in six weeks. She owes about $8 which has been borrowed from girls.

Drawing on emotional resources we can only imagine, Quok Shee resisted the pressures to have her return to China.

Trouble on Angel Island

Any artificial scarcity—such as entry into the United States—inevitably leads to a black market. In immigration it takes the form of forged papers, sale of genuine papers, smuggling, and bribes. The various Chinese Exclusion Acts had made legal entry a scarce commodity. Chinese women were even scarcer: the first act had driven the ratio of Chinese men to women to over 26 to 1. That ratio improved over time, but in 1916 there were still more than ten Chinese men for every Chinese woman in the United States. In that year, only 300 Chinese women entered the United States, of whom 111 were of the category that Chew hoped to use: "merchants' wives."

This black market was a multiracial enterprise, and those in it profited handsomely. With many willing to pay, many others were willing to be paid—kitchen help smuggled in coaching materials, watchmen looked the other way, inspectors changed their recommendations, file clerks helped files disappear temporarily while photographs were switched. Corruption flourished. It was no wonder that the Immigration Service was skeptical of Chew Hoy Quong and his "alleged wife."

Appeals

On August 6, 1917—nearly a year after Quok Shee had arrived in San Francisco, after more than eleven months of detention on Angel Island—the Circuit Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled on Quok Shee's case. Or, more precisely, on Chew v. White, Immigration Com'r, Case Number 2926.

Surprisingly, while the courts upheld the exclusion acts in general, individual Chinese had fared rather well when seeking individual relief. Of the 2,288 Chinese petitions for habeas corpus filed between 1891 and 1905, well over half had been decided in favor of the petitioners. It seemed that many judges—even avowedly exclusionist ones—had an allegiance to the rule of law: the notion that even the Chinese, as alien and unassimilable as they might be, deserved some elemental constitutional protections and due process.

Holm based his appeal of the district court's ruling on the only arguments possible under the law: that the Immigration Service had not correctly followed its own procedures and that Holm should have been allowed to present new evidence to explain the discrepancies in his clients' testimony. His arguments were completely rejected by the court of appeals. This decision again gave the Immigration Service authority to deport Quok Shee. Other developments in the courts, however, bode ill for the government.

On August 22, 1917, Commissioner White noted that "while this decision can only be viewed with satisfaction, it seems probable that a petition for rehearing will be filed by the appellant, based on the recent decision in the case of Mah Shee, Bureau No. 54176/56." In that case, the court of appeals ruled against the government because immigration authorities had refused the request of Mah Shee's lawyers that they and Mah Shee's husband be allowed to interview her jointly—without advising the lawyers that they would have granted permission to him alone. And who were the attorneys for Mah Shee? None other than McGowan and Worley, Quok Shee's original lawyers. Commissioner White was certain that Dion Holm would hear of this ruling and "present the point to the Court in an application for a rehearing." And he did.

Holm and Chew went back to the district court, launching another petition for a writ of habeas corpus, this time arguing that Quok Shee's lawyers (at the time, McGowan and Worley) had been prevented from interviewing her. The government still found a sympathetic ear in the person of Judge William C. Van Fleet, and the petition was quickly denied. Holm immediately went to the circuit court of appeals, on November 19, again petitioning for a writ of habeas corpus.

Although another six months of waiting were in store for Quok Shee while the appeal was under consideration, this one would have a very different outcome. Holm had learned that the Immigration Service had a dirty little secret: it had been withholding information.

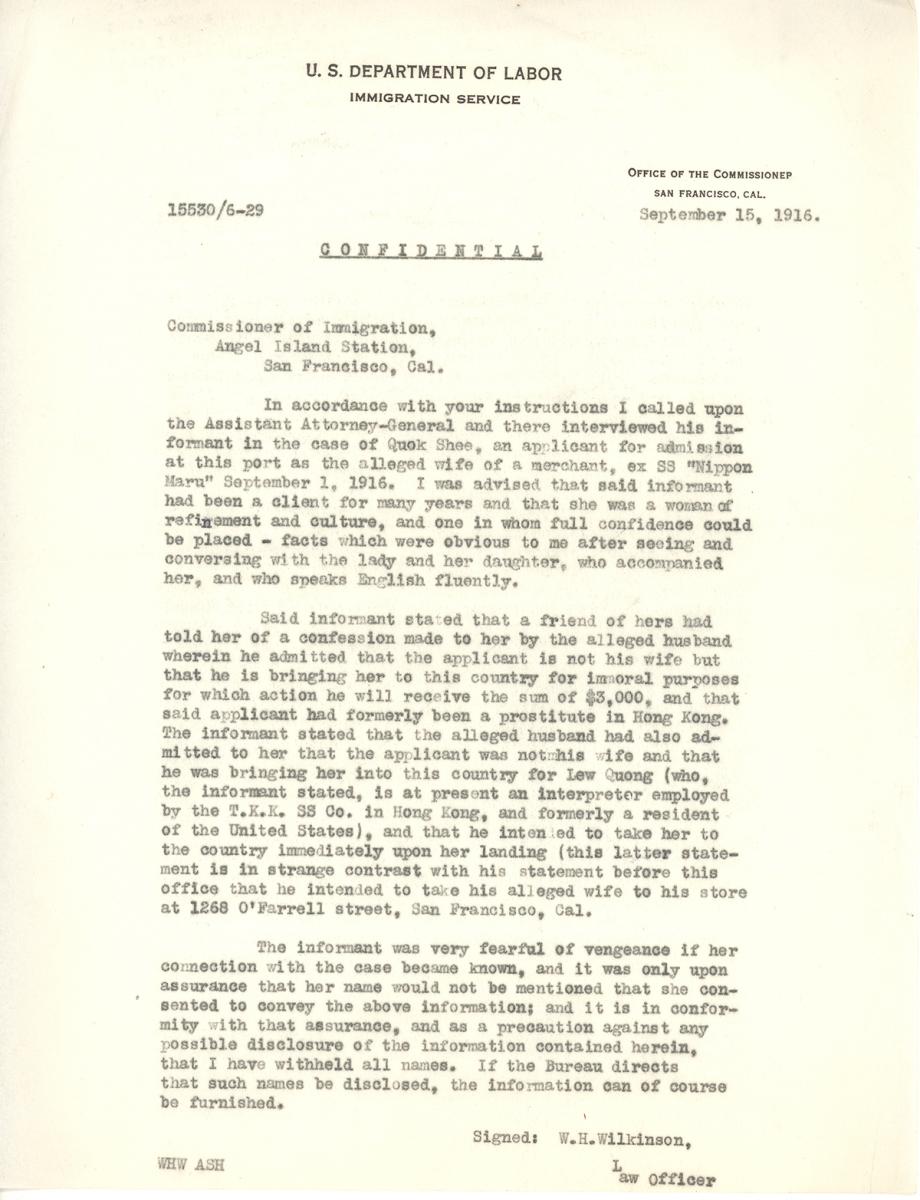

The Informer

Unknown to Quok Shee, Chew, or her lawyers, W. H. Wilkinson of the Immigration Service had secretly talked with an informer shortly after the couple arrived on Angel Island. A "confidential" memo found in Quok Shee's case file recounted the interview:

Said informant stated that a friend of hers had told her of a confession made to her by the alleged husband wherein he admitted that the applicant is not his wife but that he is bringing her to this country for immoral purposes for which action he will receive the sum of $3,000, and that said applicant had formerly been a prostitute in Hong Kong.

Commissioner White in San Francisco was convinced that Chew was attempting to bring in Quok Shee as part of "a concerted move to import Chinese prostitutes" by men from Chew's village of Nom Moon. Immigration officials were persuaded by a few minor discrepancies in testimony, buttressed by the word of an unnamed informer. One day that same testimony would be used against the Immigration Service.

A Test of Wills

If Chew was tenacious in pursuing appeals on behalf of Quok Shee, the Immigration Service was just as determined to assert its authority and prevent her entry. On November 9, 1917, and again on November 20, and yet again on December 13, Immigration Inspector Mayer interviewed Quok Shee. He did not need to threaten her—the possibility of deportation always hung above her head—but he did attempt to manipulate her isolation and vulnerability to get her to return to China voluntarily.

Quok Shee, the highest court in San Francisco has recently decided that we had a right to deport you and we would have deported you today if your alleged husband had not taken your case to the courts again. As it is you may have to wait some time until the court again decides your case. Are you willing to wait awhile for the court now to decide your case or do you still wish to be sent to China as soon as possible?

How much longer will it take to know about my case?

It is impossible to state; it may be decided within a week or two and it may not be decided for months. Did your alleged husband or your attorney or anyone else consult you about having this new case brought before the court?

No I was not consulted.

If you had been consulted about it would you have agreed to the bringing of the new case before the court?

No I would not. I would like to have my husband not bring this case in court I would rather be sent back.

How long is it since you last saw your husband?

I haven't seen him for about 8 months. He has not been to see me at the Island.

Has he sent any word to you within the last 8 months?

No. My lawyer brought me over $10 one day.

Did you ever get any money from your husband or from anyone else since you have been at the station here up until the time you received that $10 last?

No nothing. . . . I would like to have you tell my husband to send me back to China.

Do you still maintain that you are the lawful wife of your alleged husband?

I was married to him in China.

Have you any reason to think it was not a legal marriage?

Yes I think it was a legal marriage my mother had me married.

How do you explain the indifference that your husband has shown towards you since you have been here?

He is in the city. I don't know why he didn't come.

On December 13, Inspector Mayer again tried to persuade Quok Shee to demand that her lawyer drop her petition for a writ of habeas corpus.

It will probably take three or four months for your case to be decided in court.

I am not willing to wait that long, since I have waited so long already.

Would you be willing to wait two months for the Court to decide your case?

My lawyer has already promised me in two weeks, so I am not willing to wait any longer than that.

With due deference to your lawyer, I can state that your case cannot possibly be decided for two or three months at the very least.

I have already asked him to ask my friends not to appeal my case any longer. . . . I am determined to go back.

[To the interpreter]: Mrs. Wisner, please explain to her that we have no right to urge upon the Court that she be deported day after tomorrow, irrespective of the wishes of her husband unless she herself absolutely demands it of us. (Interpreter complies).

(by Applicant) I have nothing else in my mind now, except to return on the Nippon Maru on Saturday the 15th. I have nothing else to say about it; I insist upon going.

(Statement by Mrs. Wisner, the interpreter): During the last month, every time I have seen this woman, I have been asked to take a note to Mr. Hayes or the Commissioner or Mr. Mayer, begging them to use their utmost endeavors to send her back on the first Japanese boat. I have explained this statement to the applicant, and she says it is correct.

By this time, Quok Shee had been held on Angel Island for nearly fifteen months. The cycle of appeal and denial, hope and disappointment, had taken its toll. Her lawyer wrote to Commissioner White that he had applied for Quok Shee to be released on bail, and he implored the commissioner not to oppose that request:

Quok Shee is in a highly nervous state and I really believe that she will undergo great physical suffering, as well as mental if confined at Angel Island any longer. I have been told that she has on many occasions threatened to commit suicide if not released.

Even the Immigration Service was becoming concerned about Quok Shee: it would not do to have a suicide on their hands:

This woman is in a wrought up condition over the matter and it would be a great relief to her and to this office if a dismissal of the [appeal] could be secured.

Bail was denied. The appeals were not dropped. And Quok Shee did not commit suicide. Instead, she continued to bear the tedium and anxiety of confinement. It would be another four months until the court rendered its verdict.

Issue the Writ

On March 6, 1918, Dion Holm went before the circuit court of appeals in San Francisco to argue his side of Chew v. White, Immigration Com'r, Case No. 3088. His brief, printed and formally presented, is part of Quok Shee's court file. He accused the Immigration Service of refusing him an opportunity to confer with Quok Shee and of withholding information about the informer.

After nearly four weeks, the Circuit Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit, issued its ruling on April 1, 1918. The case had been heard by Judges Gilbert, Ross, and Hunt, the same trio who had heard Chew's first appeal. In his opinion, Judge Gilbert this time expressed his clear opposition to the behavior of the Immigration Service.

The denial of the right of the applicant's attorneys to interview her . . . was, we think, in itself sufficient ground for holding that the hearing was unfair. . . . Aside from that, we hold that the fact that the immigration authorities received a confidential communication concerning the applicant's right to admission, upon which they acted, and which was forwarded to the Department of Labor for its consideration, was sufficient to constitute the hearing unfair. However far the hearing on the application of alien for admission into the United States may depart from what in judicial proceedings is deemed necessary to constitute due process of law, there clearly is no warrant for basing a decision, in whole or in part, on confidential communications, the source, motive, or contents of which are not disclosed to the applicant or her counsel and where no opportunity is afforded them to cross-examine, or to offer testimony in rebuttal thereof, or even to know that such communication has been received.

The judgment is reversed, and the cause is remanded, with instruction to issue the writ.

There is something majestic in witnessing the delivery of justice, even from a vantage point of more than eighty years after the fact. Quok Shee's case had been building for so long, and the documentation already so voluminous, that I was unprepared for the effect of unfolding yet another document. This one was dated May 2, 1918, printed on a stiff, heavy paper, embossed and weighty in its official-ness: the actual order from the court of appeals, commanding that a writ of habeas corpus be issued for Quok Shee. Invoking the awesome power of the country's highest official, it left no doubt that the judicial system was now working for Quok Shee and her liberty.

References to "alleged husband" and "alleged wife" disappeared. The order recognized "Chew, as Petitioner for and on Behalf of His Wife, Quok Shee." In the name of "the Honorable Edward Douglas White, Chief Justice of the United States," the district court was told to issue the writ "as according to right and justice and the laws of the United States." That same day, the actual writ of habeas corpus issued by the district court commanded that Commissioner White bring Quok Shee, "the said person by you imprisoned and detained," before the court on May 11 to be released. Quok Shee would be free to enter the United States of America.

Reflections

At first blush, this case is both a powerful example of the harsh treatment often afforded Asian immigrants during the period of the exclusion acts and an indictment of how the Immigration Service abused the broad powers given to it.

Yet there are reasons why one might not want to write about Quok Shee's case. Hers was not "typical," being the longest known detention at Angel Island and turning out reasonably well in the end. Did "the system" work? Is this proof that immigrants could and did receive fair treatment?

Many questions remain unanswered: Who was the unnamed informant? Why did the Immigration Service decide to contact her about Quok Shee? How did Chew decide on engaging first McGowan and Worley, then Dion Holm, as his lawyers? Why, really, did the Immigration Service come down so hard on Quok Shee and Chew even before talking to the informer?

Why were they pursued so doggedly—almost obsessively—when the discrepancies in their stories seemed so minor, so plausible? Were they being shaken down, the inspectors hoping for a bribe? We can't know for certain, but these are not unreasonable suspicions, especially in light of the concurrent Densmore investigation into immigration smuggling.*

Two questions, in particular, await answers:

Was Chew really the husband of Quok Shee? Or was he, as the Immigration Service claimed, bringing her to the United States for "immoral purposes"? It seems unlikely that a merchant whose entire resources amounted to less than $1,350—his stake in the Dr. Wong Him Co. plus an IOU—could pay the substantial legal bills incurred over nearly two years of administrative appeals and court cases. Perhaps his legal costs really were underwritten by a criminal element with sinister designs on Quok Shee. Might the Dr. Wong Him Co. have been a front for individual immigrant smugglers? Or, more benignly, perhaps the legal fees were paid by the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, better known as the Chinese Six Companies. It is quite possible that all the above are true.

But something in the consistent, determined testimony of Quok Shee argues otherwise. Despite her isolation, her manipulation at the hands of Immigration Service inspectors, her fragile emotional and physical state, and the frequent examples of the women being deported and forced by the Immigration Service to leave the country, Quok Shee stuck to her story. She always insisted that she had been legally married, and that Chew was her husband. Even in moments of despair when she asked to be sent back to China, she never recanted or disavowed Chew as her husband. It would have been so easy to do. She did not, and one is inclined to believe her.

Most tantalizing of all: What happened to them? The court released her on $250 bond, the Immigration Service closed her case file, and this story ends. Or is it just a chapter that ends? Where the official documents leave off, perhaps a much longer story begins: Quok Shee's life in the United States.

We know only that in 1927, Chew told immigration authorities that his wife had complained he was not giving her enough money and had run off with another man. What became of her? Does she have descendants, and could they answer our questions about Chew Hoy Quong and his "alleged wife"?

Robert Barde is Deputy Director, Institute of Business and Economic Research at the University of California, Berkeley.

* For the origins of the Densmore investigation, see Robert Barde's forthcoming article "The Scandalous Ship Mongolia" in Steamboat Bill, published by the Steamship Historical Society of America.

Note on Sources

The author thanks Neil Thomsen and his colleagues at the National Archives and Records Administration–Pacific Region (San Francisco) in San Bruno, California, for their patient assistance in helping him piece together this story. This NARA facility houses (among much other material) microfilm copies of passenger lists for ships entering West Coast ports, immigration case files, departure records for resident Chinese, naturalization records, and Chinese business partnerships.

Quok Shee's case file is Investigation Case File no. 15530/6-29 in Arrival Investigation Case Files, 1884–1944, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, Record Group 85. Chew Hoy Quong's departure file, 12017/16433, contains information about him after the Quok Shee investigation. He went back to China in 1924 and returned to San Francisco in 1927, when he was interviewed by the Immigration Service. Again, thanks to Neil Thomsen for tracking this down.

Names, ages, sex, occupation, nationality, height, literacy, destination, and amount of money carried by the Nippon Maru's passengers are from Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at San Francisco, CA, 1893–1953, National Archives and Record Administration Microfilm Publication M1410, roll 91, RG 85.

More information about using Chinese Exclusion Investigation Case Files at NARA is found at "The EARS Have It: A Web Search Tool for Investigation Case Files from the Chinese Exclusion Era," Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration 35 (Fall 2003): 40–45.

Excellent sources about life on Angel Island include the Angel Island Foundation; the Angel Island Immigration Station (www.aiisf.org), the Chinese Cultural and Historical Project (www.chcp.org); and "Angel Island—The Ellis Island of the West." Island: Poetry and History of Chinese Immigrants on Angel Island, 1910–1940 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, reprint 1999) powerfully conveys the feelings of Chinese detainees on Angel Island.

Other useful works are Entry Denied: Exclusion and the Chinese Community in America, 1882–1943, ed. Sucheng Chan (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991); Laws Harsh as Tigers: Chinese Immigrants and the Shaping of Modern Immigration Law, by Lucy Salyer (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995); At America's Gates: Chinese Immigration During The Exclusion Era, 1882–1943, by Erika Lee (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003); "Chinese Women Immigrants and the Two-Edged Sword of Habeas Corpus" in Genny Lim, ed., The Chinese American Experience: Papers from the Second National Conference on Chinese American Studies (San Francisco: Chinese Historical Society of America, 1980), pp. 48–56; and Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco, Judy Yung (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995).