The EARS Have It

A Web Search Tool for Investigation Case Files from the Chinese Exclusion Era

Fall 2003, Vol. 35, No. 3

By Robert Barde, William Greene, and Daniel Nealand

Angel Island and its immigration station in San Francisco Bay hold a salient place in the history of Asian Americans and in American history. The exact number of immigrants who passed through or were detained at Angel Island Immigration Station during its existence (1910–1940) is unknown, with estimates ranging toward one million on the high end to the more modest 300,000.

While the numbers are relatively small compared to Ellis Island in New York Harbor (perhaps 22 million), Angel Island Immigration Station's place in the consciousness of Americans—especially on the West Coast—is writ large. This is due to its major significance for Asian American immigration history during much of the period covered by federal laws and policies under the Chinese Exclusion Act and its successors (1882–1943). In these years, San Francisco was the port of entry for approximately 90 percent of Asian-Pacific arrivals in the United States.

The parts played by Angel Island and the Immigration Service were integral to the longer drama that began in 1882 with the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act—an unprecedented measure barring immigration on the basis of both race and class. While Chinese laborers (including owners and managers of many types of businesses) could not enter, exceptions were made for such groups as teachers, merchants, government officials, and students.

Enforcement of Chinese Exclusion was initially given to the Customs Service (Treasury Department), then transferred to the Bureau of Immigration (Department of Commerce and Labor) in 1903. Before the opening of the Angel Island Immigration Station, the interrogation and detention of aliens was conducted at the detention shed on the San Francisco wharf of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company. Both facilities existed to enable the exclusion of Asians—first and foremost the Chinese, who composed the great majority of those detained for investigation and possible exclusion, but also Japanese, Koreans, Indians, and others of non-European origin.

The Immigration Service, in its efforts to prevent alleged "undesirables" from entering, detained many such early arrivals and sought to determine their eligibility to enter the country. The subjects of the resulting investigation case files were overwhelmingly Chinese, but much smaller numbers of files for many other nationalities are also included—Japanese, Koreans, South Asians, Filipinos, Russians, Latin Americans, and the odd European. And not all the "Chinese" were Chinese nationals—a significant fraction were native-born Americans of Chinese ancestry attempting to reenter the United States.

Of all the so-called "Chinese case files" at the National Archives–Pacific Region (San Francisco), located in San Bruno, California, the oldest are files for two people who arrived in San Francisco aboard the SS Oceanic on May 12, 1884. File 9228/1601 concerns Lui Fung, a merchant from Hong Kong. File 9228/1630 contains affidavits submitted on behalf of Leong Cum, a young woman who had been born in Lewiston, Idaho Territory, in 1868 and was returning to the United States after a visit to China. Both were detained (most probably in the Pacific Mail's Detention Shed) before being admitted: Lui Fung on May 13, Leong Cum a day later.

Their files are part of a collection of 250,000 investigative case files at NARA–San Francisco. Usually, though inaccurately, referred to as the "Chinese Exclusion Files," these files might more properly be called early "Arrival Investigative Files." They represent some of the hundreds of thousands of new arrivals and returning residents who passed through the ports of San Francisco and Honolulu between 1882 and 1955, which encompasses the Chinese Exclusion period.

The NARA–San Francisco files are the most comprehensive record of this aspect of American history. Similar sets of files reside in southern California, Seattle, Chicago, Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, but the collection in NARA–San Francisco is by far the largest. Nationwide, these files "are remarkable compared to other INS immigrant files of the same era in that they survived in their original form," according to Immigration and Naturalization Service historian Marian L. Smith.

Historians and genealogists have long found it difficult to survey this vast collection to locate specific files. But a recently created web site now makes it possible to search a portion of the investigation case files index over the Internet. The Early Arrivals Records Search (EARS) was developed by the Institute of Business and Economic Research and the Haas School of Business (both at the University of California, Berkeley) and NARA - San Francisco. The original (physical) case files are still available only in paper form in San Bruno, but photocopies can be ordered by telephone or email. The EARS web site, however, reveals whether NARA has a case file for a particular person, plus the case file number and a smattering of information about that person.

What Is in a Case File?

A typical investigation case file contains the individual's name, place and date of birth, physical appearance, occupation, names and relationships of other family members, and family history. Specific INS proceedings are usually documented. Because of the nature of INS investigations, case files also provide links to file numbers for related cases, including those of other family members.

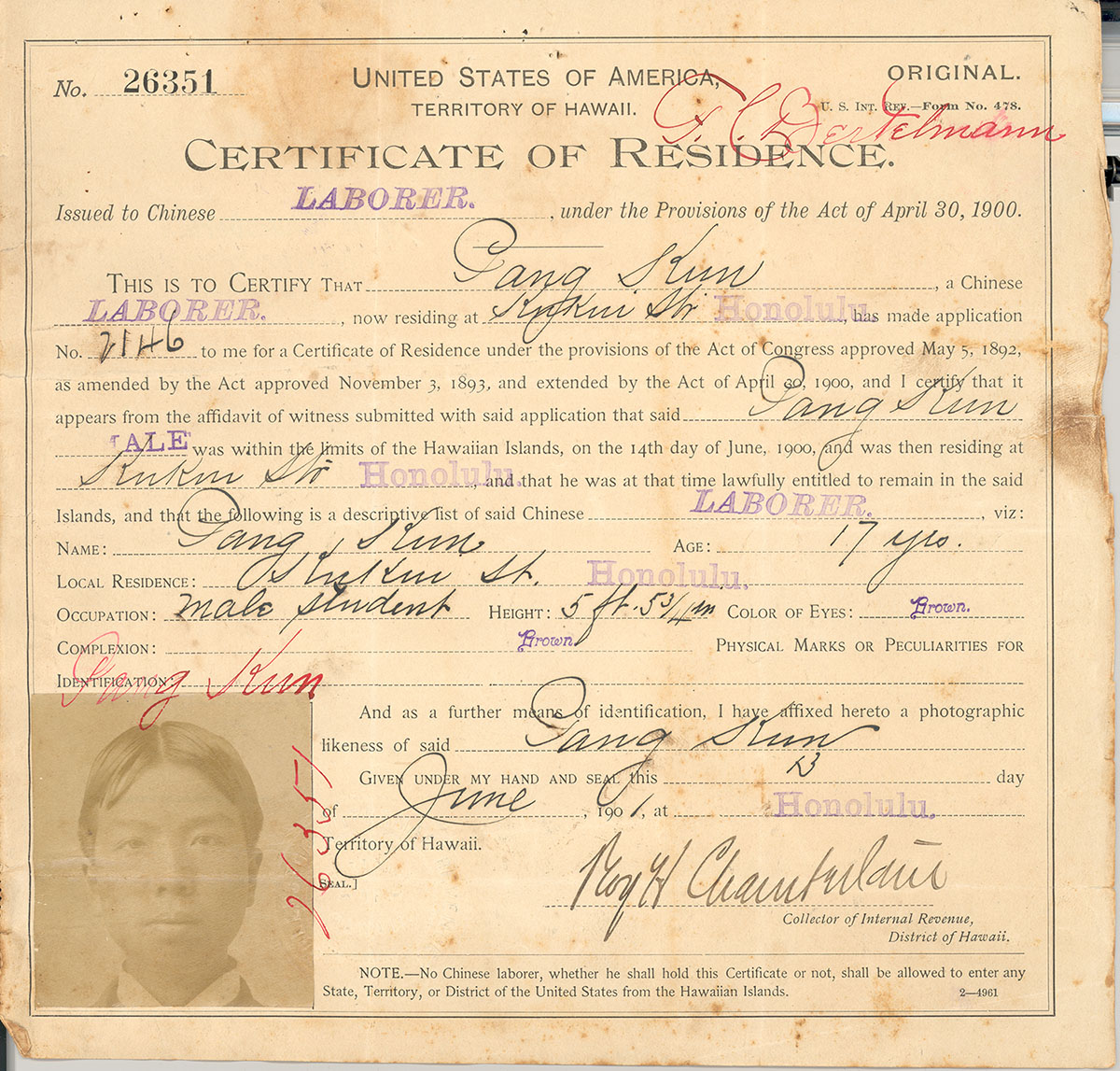

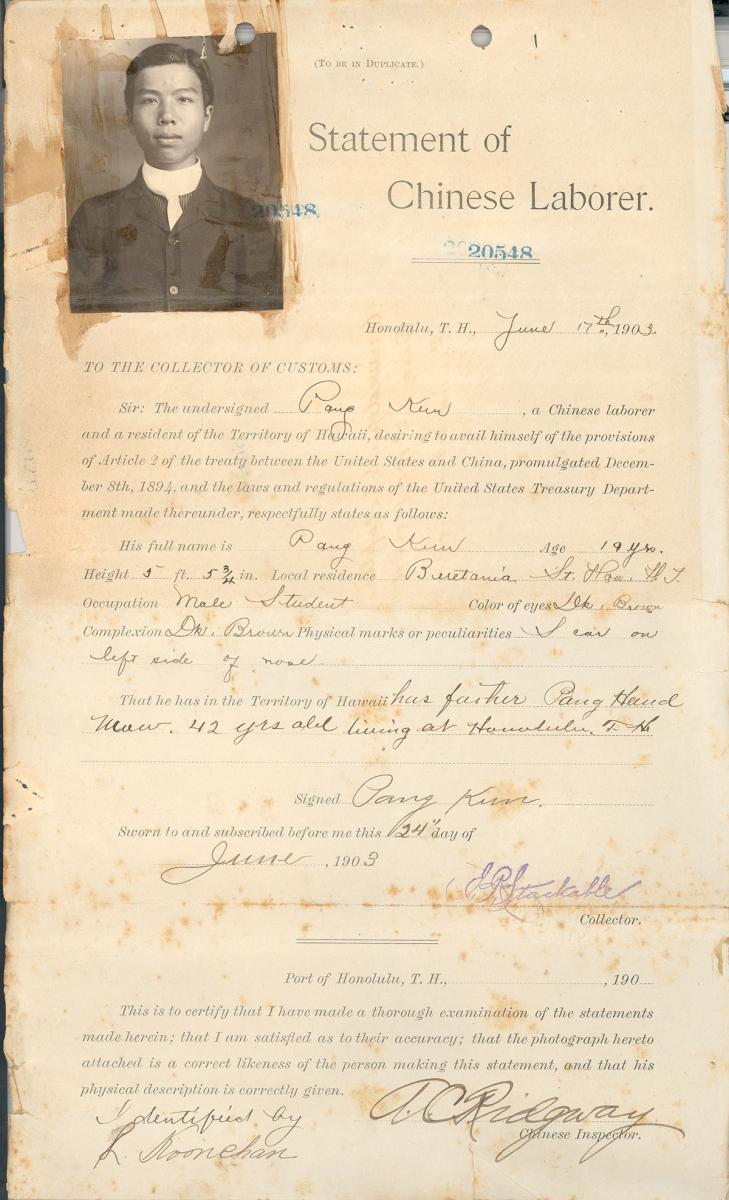

The files may contain certificates of identity and residency; correspondence; coaching materials used by "paper sons"; INS findings, recommendations, and decisions; maps of immigrant family residences and villages in China; original marriage certificates; individual and family photographs; verbatim transcripts of INS interrogations and special boards of inquiry; and witnesses' statements and affidavits. Some files are rather skimpy, while some are extraordinarily voluminous.

What Case Files Does NARA–San Francisco Have?

Before 1944, each INS district office developed its own filing systems. Name indexes to case files are available for only a few of the offices. NARA volunteers and students have created a partial database index to the case files of the INS San Francisco District Office; about 80 percent of the case files of the INS Honolulu District Office have already been indexed up to 1944.

From the Honolulu District Office of the Immigration and Naturalization Service

An index to more than 16,600 "Chinese Exclusion era" case files—a number of which actually deal with Japanese and Filipinos—created between 1903 and 1944.

From the San Francisco District Office of the Immigration and Naturalization Service

An index to some 19,600 "Chinese Exclusion era" case files from 1884 to 1913, with the bulk of the files coming from the period 1906–1913. There are many thousands more case files for the period 1914–1955 that await indexing. The great majority of INS investigation files in NARA–San Francisco's collection relate to Chinese Americans, but many other nationalities are included.

What Is NOT in the EARS Database?

Not every arrival resulted in an investigation case file. Many pre–World War I arrivals from India, Japan, Korea, the Philippines, and other countries were not investigated by INS to the same extent as the Chinese. In particular, Filipino arrivals were rarely investigated before the creation of the Philippine Commonwealth Government in 1934. Prior to the Immigration Act of 1917 and creation of an "Asiatic Barred Zone," INS officials in San Francisco and Honolulu generally investigated non-Chinese immigrants only in certain cases, such as when immigrants were considered "likely to become public charges" or were suspected of political activity and when some provisions of existing immigration law could be applied.

In some instances, the INS created case files for certain individual Asian immigrants and Asian Americans but then destroyed the records, as happened in 1948 with the San Francisco District case files of Filipinos desiring to be repatriated at government expense between 1935 and 1940.

While the NARA–San Francisco collection includes case files created by INS San Francisco for almost all "Japanese Picture Brides" during the 1908 to 1920 period, many post-1920 files for Japanese immigrants and their descendants have been reported missing. This is possibly due to INS-Department of Justice use related to World War II internment of Japanese Americans.

Many surviving INS files from San Francisco and Honolulu are no longer at NARA–San Francisco. Any number of actions could have resulted in the immigrant's file being shipped to some other INS district office. From there, the file may have been transferred to another NARA regional archives, or it may still reside with the INS. This might have happened if the person became a citizen or reentered the country through another port, for instance.

Perhaps thirty thousand to sixty thousand INS San Francisco files from the Exclusion period for various, mostly Asian American, immigrants have been "uploaded" into modern (1940 forward) INS Alien Registration, or "A Files," collections, which remain in INS custody.

More San Francisco Arrival Investigation files data, doubling the size of the EARS database and making it complete through 1921, should come online within a year. Indexing the remaining nearly 200,000 files will require a massive, ongoing infusion of volunteer effort and NARA staff resources.

Additions to the EARS online index will make it an extraordinarily powerful tool for researchers interested in this priceless primary resource for American, and particularly Asian American, history.

About EARS

Questions about the EARS web site can be directed to Mr. Barde at barde@uclink4.berkeley.edu. Questions about access to individual case files should be directed to NARA: 650-876-9009; email sanbruno.archives@nara.gov. The data were supplied by the National Archives and Records Administration–Pacific Region in San Bruno, California. At the University of California, Berkeley, Lisa Martin and Neal Fujioka (both at the Haas School of Business) performed the database development, web programming, and site design, and Patt Bagdon (Institute of Business and Economic Research) designed the web page banner.

Note on Sources

The exact number of immigrants passing through Angel Island is unknown because a 1940 fire that destroyed the Administration Building there also destroyed most of the immigration station's administrative records. Immigration totals for the station in the INS's headquarters files, now at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, have not yet been discovered. The estimate of 300,000 is based on the 340,000 "Alien Arrivals at the Port of San Francisco, 1910–1940," of whom approximately 70 percent were detained at Angel Island. Alien arrivals data are presented in Maria Sakovich, "Angel Island Immigration Station Reconsidered: Non-Asian Encounters with the Immigration Laws, 1910–1940" (MA thesis, Sonoma State University, 2002). The detention rate is from unpublished data of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, cited in Robert Barde and Gustavo Bobonis, "Detained at Angel Island: Empirical Evidence" (forthcoming).

For a good description of what an adventure it can be to find a case file, see Neil Thomsen, "No Such Sun Yat-Sen: An Archival Success Story," Chinese America: History and Perspectives, Journal of the Chinese Historical Society of America 11 (1997).

For an example of a voluminous case file, see Robert Barde, "An Alleged Wife: One Immigrant in the Chinese Exclusion Era" Prologue 36 (Spring 2004).

Authors

Robert Barde is the EARS project organizer and Academic Coordinator at the Institute of Business and Economic Research, University of California, Berkeley.

William Greene is an archives specialist at the National Archives and Records Administration–Pacific Region (San Francisco) in San Bruno, California.

Daniel Nealand is archival operations director, National Archives and Records Administration–Pacific Region (San Francisco) in San Bruno, California.