Beyond the Box Score

Baseball Records in the National Archives

Spring 2006, Vol. 38, No. 1

By David A. Pfeiffer and John Vernon

About all the "national pastime" and the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) would seem to have in common is the word "national."

Experienced users of NARA understand (or think they do) what kinds of documentary materials are to be found among its holdings. They have learned, after all, that this institution is the official repository for only the permanently valuable records of the federal government. Moreover, since Uncle Sam is a decidedly public institution and baseball is a privately governed cultural enterprise, why should anyone other than the greenest researcher think NARA might contain records relating to baseball?

However, to overlook the National Archives as a source of baseball information is tantamount to a rookie hitter going up to the plate without a bat because he doesn't think he can hit major league pitching anyway. In fact, the National Archives contains numerous documents on a variety of baseball-related subjects.

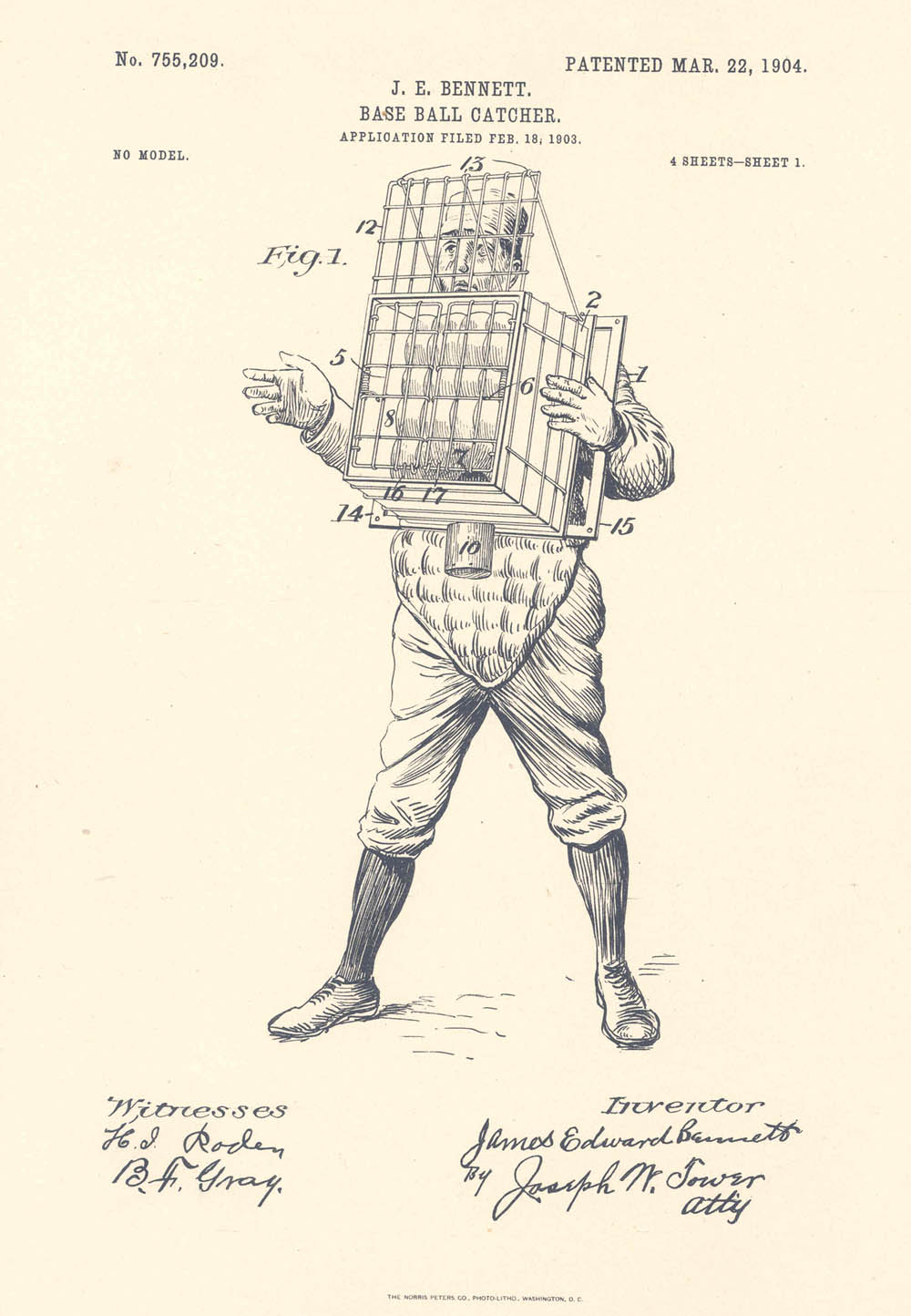

For example, within the National Archives system (including regional archives and presidential libraries), a researcher can discover player-related civil suits pursued in federal courts; military service recreational activities; a surveyor's sketch and notes for a proposed new stadium in Washington, D.C.; equipment patent drawings; a political cartoonist's pen-and-ink rendering of a harried President trying manfully to field a barrage of congressional amendments; published antitrust hearing findings; a restraint-of-trade action filed by one bubble gum company against another over issuance of player cards; and a World War I vintage picture of attractive female ushers at a ball game.

There's also an equally charming and seldom-glimpsed image of Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, and Tris Speaker—three one-time luminaries of the game in their baseball dotage—posing together in 1941 in connection with war bond and Army-Navy relief fund efforts as well as numerous photographs of amateur and professional players taken for foreign propaganda and cultural purposes. All exist as legitimate documentary evidence of federal program activity.

Certainly, the groups of "baseball" records to be found here—related to the game's players, fans, employment conditions, business practices, and hoary traditions—did not arrive by accident.

Their presence instead suggests that government entities that collected these records must have had pretty good reasons, so prospective researchers first need to find out what reasons the government would have to get involved in this most American of sports, thus creating this rich trove of records about baseball.

Audiovisual Records

So much of our understanding and appreciation of the game as a cultural and societal phenomenon is necessarily visual. Consequently, much of the most compelling and useful data about it is best conveyed through photograph, film, or videotape. For some Archives patrons, films and photographs that recall earlier days spent at various ballparks may hold the greatest appeal. Special media records, far more than their written counterparts, tend to have item-level finding aids that allow the researcher to locate materials fairly quickly.

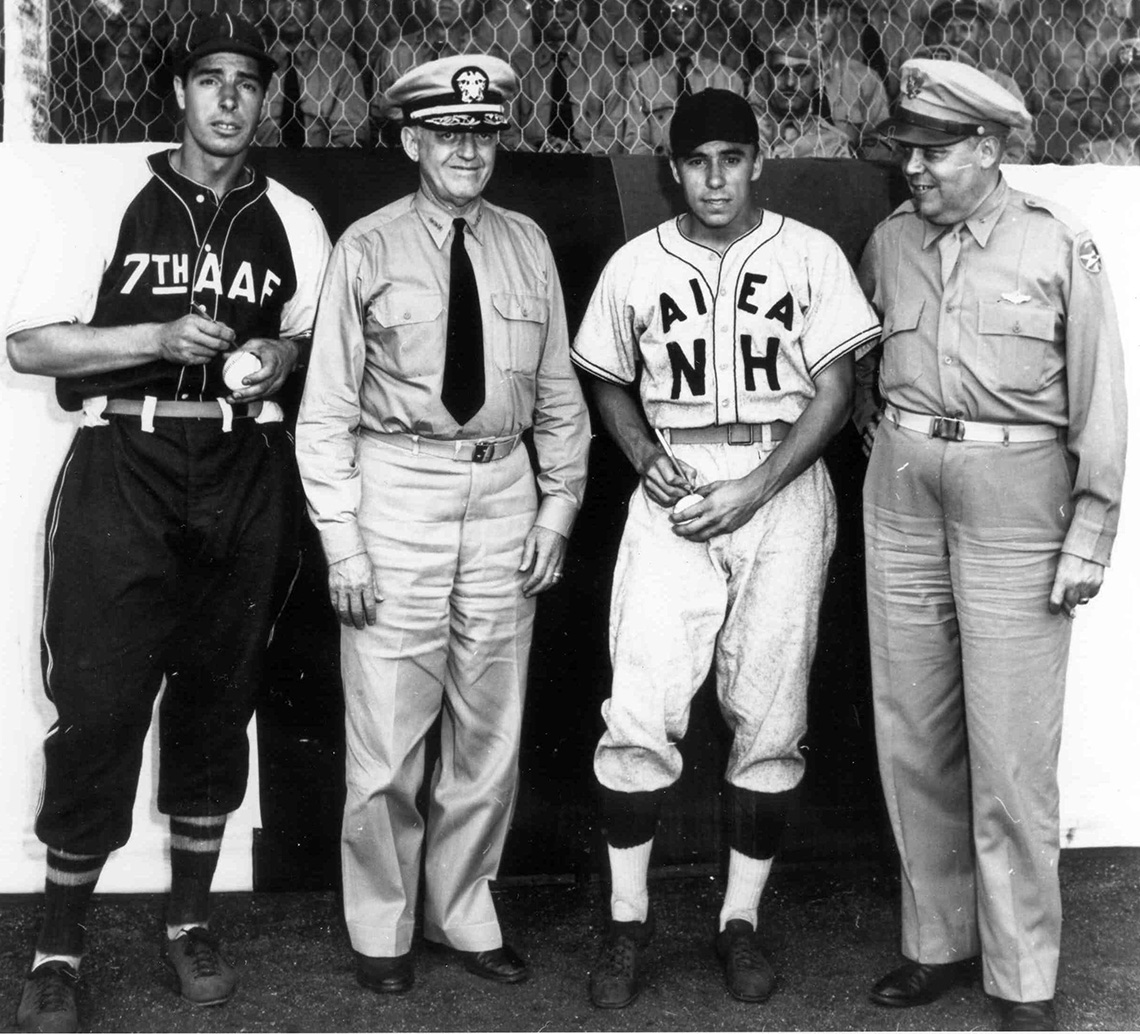

The Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer for the Army (Record Group 111) and the Records of the Department of the Navy (Record Group 80) offer good examples of baseball records that researchers might overlook unless they have thought sufficiently about how baseball can intersect with the conduct of military affairs. Both of these record groups are rich in images of baseball being played in China, Japan, Guadalcanal, France, Italy, and in other areas where American troops were stationed from roughly the World War I era to the mid-1950s.

In exotic locales, enlisted men and officers alike either competed in games or watched others of greater skill perform for them. Numerous major leaguers who were drafted into the armed services played for and with other American troops overseas and at home. As a result, where else could one come up with a photograph of the Navy's Pee Wee Reese and the Army's Joe DiMaggio in Hawaii posing in July 1944 with two beaming superior officers before their respective service teams clashed? Or of fellow professional players, catchers Moe Ginsberg and Joe Garagiola, squatting in front of a baseball dugout in October 1945? Even more unlikely would seem the relaxed shot of future Baseball Hall-of-Famers Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig taken when their team, the New York Yankees, played at West Point, New York, in May 1927. That year Ruth hit 60 home runs for what many baseball experts believe was the most powerful Yankee team of all time. These are but a small sample of the range of baseball-related images that can be found within these two military record groups.

Another engaging photographic collection of the World War II period (1942–1946) is to be found in Record Group 208, Records of the Office of War Information (OWI). Three different series within Record Group 208 contain photos of relevance to baseball:

- the "FS" series of shots accompanied Feature Stories on significant baseball teams, events, and various aspects of the game to show a slice of American recreational life and culture to a foreign audience;

- the "PU" series contains portraits of significant baseball personalities along with those of other entertainment figures; and

- the "LU," or Life in the United States, series contains some interesting images of prominent Americans playing baseball as is seen in a candid 1942 shot of renowned actor and singer Paul Robeson swinging a bat. Equally compelling is a shot of the DiMaggio brothers, Joe, Dom, and Vince, all of whom at one time graced the big leagues.

In 1953 the United States Information Agency (USIA) was established to perform a similar propaganda function abroad as the OWI had previously. After purchasing the New York Times Paris Bureau photographic files, the USIA had at its disposal numerous photographs of well-known celebrities of the 1920s–1940s, including those of many baseball luminaries. These are often located in the "NT" series of the Records of the U.S. Information Agency (Record Group 306). One unusual and riveting image shows a relaxed Babe Ruth with enthusiastic African American fans in April 1928 at the Atlanta ball park. A kindred source to consult for baseball shots is the USIA's "PS" series, the agency's central Picture Story photographic file.

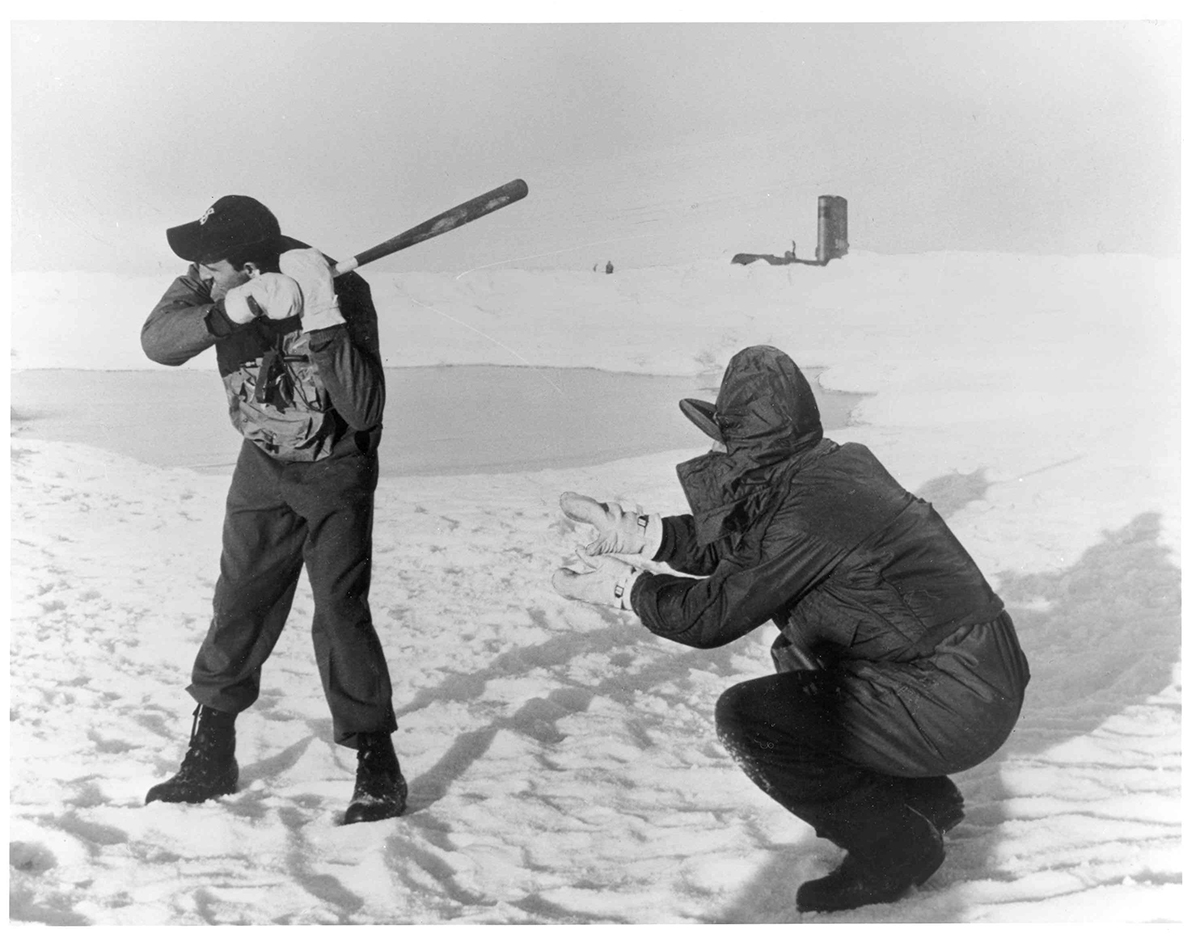

In PS files a diligent researcher can find such gems as the photograph taken of baseball being played at the North Pole with a submarine in the background, or an early photograph of earnest young Jackie Robinson of the Brooklyn Dodgers at Flatbush's old Ebbetts Field. It is noteworthy that Robinson wields a first baseman's mitt in the picture. The only time he played that position regularly was in 1947, the year he integrated the major leagues. In this shot, he seems to be defying gravity and long-standing racial barriers with equal aplomb.

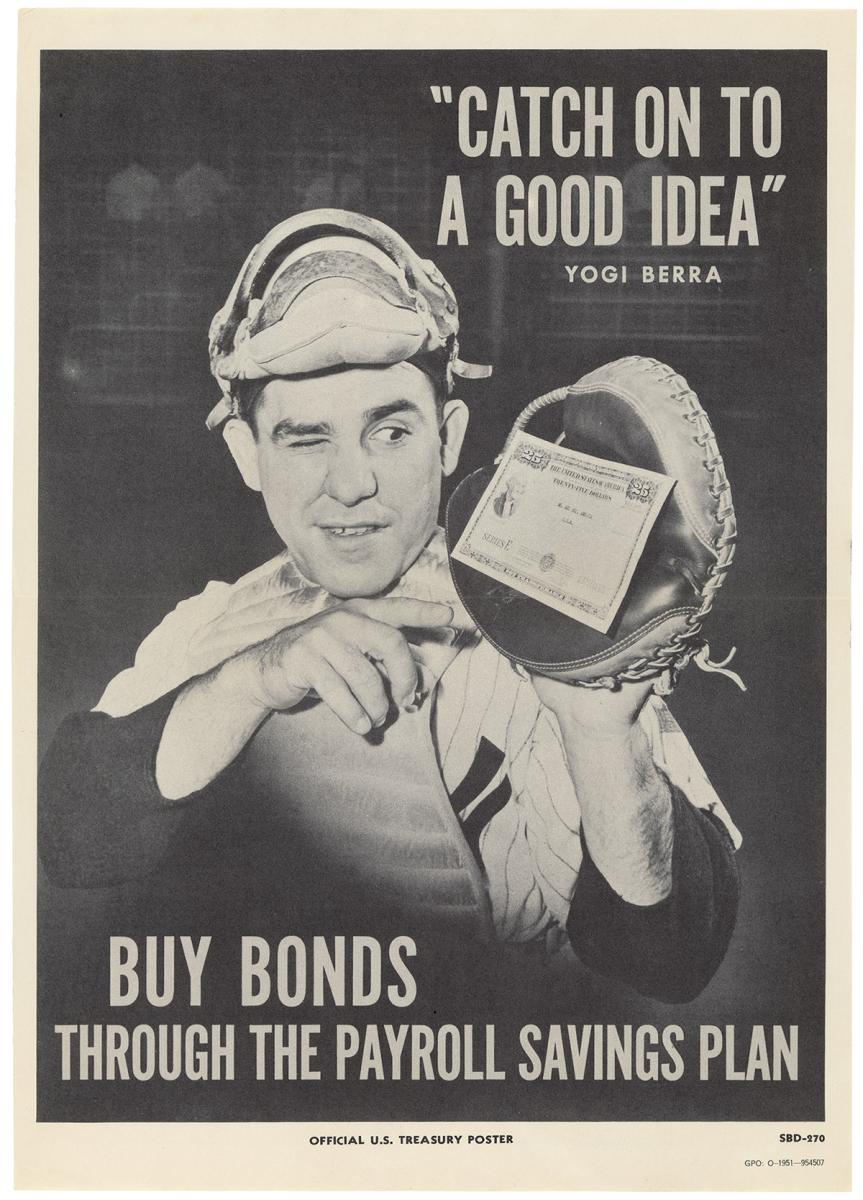

Two other agencies used the reputations and images of big leaguers to sell their messages. During World War II the Department of the Treasury (Record Group 56) used major baseball stars Babe Ruth and Carl Hubbell among others to encourage patriotic Americans to buy war bonds. Later, the Treasury Department used photographs of prominent entertainers and athletes, including such well-known ball players as Yogi Berra, Ted Williams, and Ralph Kiner, to promote the purchase of savings bonds.

In Forest Service files (Record Group 95) are poster portraits of such popular later-generation major leaguers as Don Sutton, Orel Hershiser, and Mike Sciosa—sometimes appearing with Smokey Bear—advocating fire safety awareness among national forest campers.

The role of U.S. Presidents in baseball traditions is documented in the numerous Abbie Rowe photographs located in the Records of the National Park Service (Record Group 79). These images taken over the years from FDR's through LBJ's administration show various happy Presidents "throwing out of the first ball" to inaugurate each new season in Washington, D.C.

It is worthwhile to note that sometimes individual or collective donors offer clearly private document collections to the National Archives. The institutional criterion for deciding whether or not to accept an offer is simple and pragmatic: Can these materials foster deeper researcher understanding of historically important federal activities even though they represent neither official interaction between government officials nor the parties affected by those activities?

NARA's motion picture holdings give dramatic testimony to baseball's cultural prominence within American life. Donated Paramount, Movietone, and Universal news footage documents annual All-Star Games and the World Series. There is also ample coverage of National Baseball Hall of Fame inductions, Old Timer games, celebrity contract signings, spring training activities, ballplayer golf tournaments, high-profile autograph signings, and the like.

The Written Word

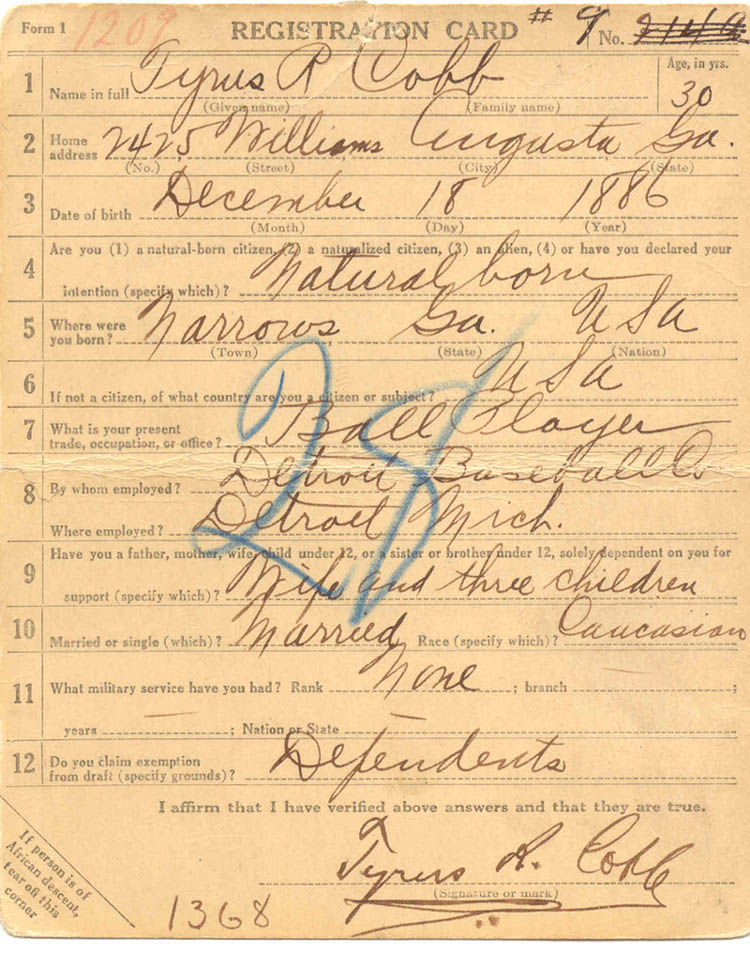

Textual materials relating to baseball are also widely scattered throughout the records of the National Archives. While there are no discrete collections of baseball-related records, documents such as invention patents, antitrust cases in federal courts, a Federal Trade Commission case involving bubblegum companies Topps and Fleer, Ty Cobb's draft registration card, and the so-called "green light letter" exist in apparently unrelated collections.

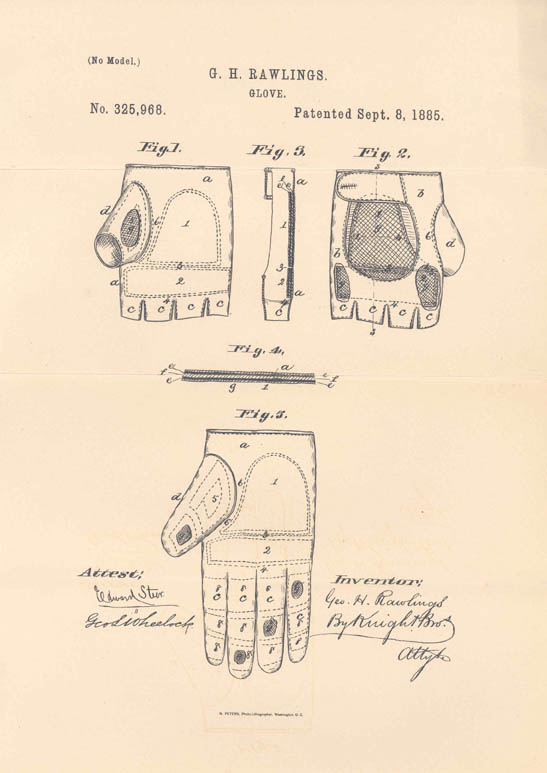

In the records of the Patent and Trademark Office (Record Group 241) there are several invention patents relating to baseball, such as the patents for the baseball bat, glove, catcher's mask, and the baseball itself. John A. Hillerich of Louisville, Kentucky, applied for and received many patents for the baseball bat. Hillerich was the owner of J. F. Hillerich and Sons, later to become Hillerich & Bradsby Company, manufacturer of the famous Louisville Slugger bats. One application, dated October 31, 1902 (Invention Patent #716,541) for improvements in baseball bats involved the hardening of the surface of the bat. The purpose of this application was to promote the batter's ability to drive the ball for more distance, to preserve the body of the bat from chipping and splintering easily, and finally to improve the finish and appearance of the bat. This invention was patented on December 23, 1902.

Another of Hillerich's patent applications, dated June 8, 1904, declared as its objective to decrease the hitting of foul balls by the batter and to increase the number of fair balls hit (Invention Patent #771,247, patented on October 4, 1904). Hillerich proposed modifying the hitting surface of the bat with regular indentations.

Other famous names appear in invention patents. George A. Rawlings, owner of a well-known sporting goods store in St. Louis and later manufacturer of a line of sporting goods, invented improvements in the baseball glove. In an application, patented on September 8, 1885 (Invention Patent #325,968), Rawlings proposed the use of padding in the fingers, thumb, and the palm of the gloves for the "prevention of the bruising of the hands when catching the ball." The felt/rubber combination in the padding provided for increased flexibility and thus improved protection from bruising.

Benjamin F. Shibe, one of the original owners of the Philadelphia Athletics and the person after whom Shibe Park in Philadelphia was named, patented on February 27, 1883, an improvement to the baseball itself (Invention Patent #272,984). By carefully combining the ingredients of yarn, India-rubber, and cement, Shibe claimed that his invention would better maintain the spherical shape of the ball even after repeated hits by baseball bats. Part of the improvements involved the tighter winding of the yarn and integrating the yarn in the cement to maintain the integrity of the sphere.

An improvement to the catcher's mask was patented by Alexander K. Schaap, of Richmond, Virginia, on October 23, 1883 (Invention Patent #287,331). Because catchers had difficulty removing their masks when a foul ball above the plate was hit, Schaap added a hinge to the upper part of the mask.

Perhaps one of the most bizarre baseball-related inventions was the "baseball catcher" by James E. Bennett (Invention Patent #755,209), patented on March 22, 1904. This contraption basically replaced the catcher's mitt with a wire cage placed on the catcher's chest. The object of the invention was to protect the catcher's hands so that the hands would not come in contact with the ball until it was time to throw it back to the pitcher. The invention was a rectangular open-wire frame body reinforced by slotted walls of wood. The impact of the ball on the catcher's chest is protected by springs on the rear wall of the device. After the ball has passed through the open front end, it closes automatically. At the bottom of the device is an opening where the ball passes into a pocket where it is retrieved by the catcher. The device also includes a wire mesh on the top to protect the catcher's face. The patent drawings do an excellent job of illustrating this device.

Numerous antitrust cases involving baseball are found in the federal court records. One of the most significant is The Federal League of Professional Baseball Clubs v. The National League, the American League, etc. (Equity Case #373, January 1915, Record Group 21), which was tried in the District Court of the Northern District of Illinois—Eastern Division. This antitrust action brought by the Federal League alleged that major league baseball was in violation of the antitrust and antimonopoly statutes and that the league's player contracts restricted fair trade and commerce. Additionally, the Federal League charged that there was a conspiracy among the American and National League presidents (the defendants in the case) to destroy the upstart league.

Conversely, the defendants charged that the Federal League was stealing their players who were signed to exclusive, not voluntary, contracts with the major league teams. Consequently, the major league presidents allegedly threatened that any player who jumped leagues should thereafter be barred from playing in organized baseball.

The case was heard by Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, later the first commissioner of baseball (1920–1944). The parties settled the case later in the year. The majors partially compensated the debt-ridden Federal League owners, the Federal League withdrew its lawsuit, and two Federal League owners purchased the St. Louis Browns and the Chicago Cubs.

In the case file are several affidavits from major league team owners, including Charles Ebbets of the Brooklyn Dodgers and Charles Commisky of the Chicago White Sox, alleging that the Federal League was attempting to steal their players. Also included is a letter from Ebbets to Joe Tinker, requesting him to sign a contract with the Dodgers.

Another landmark antitrust case is Curtis C. Flood v. Bowie K. Kuhn (407 U.S. 258), argued before the Supreme Court of the United States on March 20, 1972 (No. 71-32, Record Group 267). This case paved the way for free agency in professional sports. Flood was a professional baseball player traded to another club without his previous knowledge or consent. He brought this suit after being refused the right to negotiate his own contract with another major league team. The District Court rendered judgment in favor of the defendants, and the Court of Appeals affirmed.

Giving the opinion of the Court, Justice Harry Blackmun upheld the lower courts' rulings and ruled that the longstanding exemption of professional baseball from the antitrust laws was an "established aberration" and therefore was entitled to the benefit of the status quo. Further, he stated that any changes to baseball's antitrust exemption should be a matter for legislative, not judicial, resolution. Even though Flood lost this case in the Supreme Court, later suits brought by Catfish Hunter and Andy Messersmith eventually overturned baseball's reserve clause.

The docket files of the Federal Trade Commission also include antitrust cases. Notable among these is a restraint-of-trade action filed before the FTC by one bubble gum card manufacturer alleging that another unfairly controlled the very lucrative baseball picture card market in 1962. The FTC charged the Topps Chewing Gum Company, on behalf of the Frank H. Fleer Trading Card Company, with creating and affecting a monopoly in the manufacture and distribution of baseball picture cards by resorting to various unfair practices. Also, the FTC charged Topps with entering exclusive long-term binding baseball card contracts so that other companies would not be able to compete.

A decision in the matter of Topps Chewing Gum, Inc., was issued on August 7, 1964 (FTC Docket #8463, Record Group 122). In the decision, the FTC stated that Topps was guilty of violating the Sherman Anti-Trust Act in its domination of the baseball picture card market. Therefore, the commission ordered that Topps cease and desist from entering into any contract with any professional baseball player, manager, or coach for exclusive rights to use their pictures, names, or biographies for two years after November 1, 1966.

The contents of the docket are rich with baseball lore. The docket contains motions, petitions, orders, briefs, exhibits, transcripts of testimony, the initial decision, and findings of fact. The exhibits submitted as evidence in the case include colorful advertising posters, player endorsement contracts, prize lists, marketing surveys, sales promotions, and 30 years of baseball cards.

There are numerous other court cases involving baseball, baseball players, or even baseball equipment among the records of the National Archives. One example is the equity suit involving Hillerich & Bradsby Company v. Hanna Manufacturing Company, in 1933. Hillerich and Bradsby were the manufacturer of the famous Louisville Slugger bats. This equity case claimed trademark infringement and the violation of the plaintiff's exclusive right to use certain baseball players' names on its baseball bats. The court found for Hillerich and Bradsby, saying that Hanna violated H&B's property rights of the names and that the use of the names was a false representation by Hanna. This case was assigned Equity Case #72 and was tried in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern (Athens) Division of the Middle District of Georgia (Record Group 21).

Baseball players served in the military during World War I and World War II, and many of them registered for the draft. The Office of the Provost Marshal General supervised the registrations of approximately 24 million men for the World War I draft. The Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, are in the Records of the Selective Service System (World War I), Record Group 163, in the National Archives regional archives. One of the more notable cards is the card for Ty Cobb that is in the National Archives Southeast Region in Atlanta.

Particularly noteworthy among documents relating to baseball in the holdings of the National Archives is the so-called "green light letter" in the Franklin D. Roosevelt FDR Library. On January 14, 1942, the commissioner of baseball, Judge Kennesaw Mountain Landis, wrote a letter to President Roosevelt, asking for permission for major league baseball teams to operate for the 1942 season.

FDR wrote back, giving the "green light" for the 1942 season. In the letter, dated January 15, FDR observed that "I honestly feel that it would be best for the country to keep baseball going. There will be fewer people unemployed and everybody will work longer hours and harder than ever before. And that means that they ought to have a chance for recreation and for taking their minds off their work even more than before. Baseball provides a recreation which does not last over two hours . . . and which can be got for very little cost." He added that he hoped that there would be more night games so that workers on the day shift could see more games. And finally, he remarked that players who are of military age should go into the services and that "even if the actual quality of the teams is lowered by the greater use of older players, this will not dampen the popularity of the sport." Thus, organized baseball continued to play during World War II.

The examples discussed here give just a taste of what lies in the National Archives. Many more archival documents potentially useful for learning about baseball await the diligent researcher. The scouting process for locating these and many other undiscovered records is similar to that employed in baseball for scouting players. It takes determination, strategy, resourcefulness, planning, and an open mind to discover can't-miss prospects. Both explorations are labor-intensive, so patience is a must. If doing research at the National Archives is comparable to playing in the big leagues, remember that the path to the latter is usually somewhat rocky, the travel and playing conditions formidable, and the work back-breaking. So by comparison, the baseball researcher's search effort here is a snap!

Note on Sources

The photographs mentioned in this article are in the custody of the Special Media Archives Services Division, National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

The invention patent files among the records of the Patent and Trademark Office (Record Group 241) and the Federal Trade Commission dockets (Record Group 122) are in the custody of the Textual Archives Services Division, also in the National Archives at College Park.

The Flood v. Kuhn case is among the holdings of the Records of the Supreme Court of the United States (Record Group 267), in the Textual Archives Services Division, National Archives, Washington, D.C. Additional information concerning this case, including a good case summary, is located at the National Archives web site under the Archival Research Catalog and also at the Antitrust Case Browser (summaries of key antitrust cases by Prof. Anthony Becker).

Equity Case #373, The Federal League of Professional Baseball Clubs v. The National League, the American League, etc., tried in the District Court of the Northern District of Illinois–Eastern Division (Record Group 21), is in the custody of the National Archives–Great Lakes Region. Additional information concerning the case is located at BaseballLibrary.com.

The Hillerich & Bradsby Company v. Hanna Manufacturing Company case (Equity Case #72) that was tried in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern (Athens) Division of the Middle District of Georgia (Record Group 21) and the Ty Cobb draft registration card (Record Group 163) are located in the National Archives–Southeast Region. Again, additional information on these records is located in NARA's online Archival Research Catalog.

The "green light letter" is located in the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library in Hyde Park, New York.

The Topps/Fleer restraint-of-trade action is discussed in John Vernon and Richard E. Wood, "Baseball, Bubble Gum, and Business: The Making of an Archives Exhibit," Prologue: Journal of the National Archives 17 (Summer 1985): 79–91. FDR's "green light" to baseball is featured in Gerald Bazer and Steven Culbertson, "When FDR Said 'Play Ball': President Called Baseball a Wartime Morale Booster," Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration 34 (Spring 2002): 58–63.

Additional court cases relating to baseball may be found in National Archives regional archives across the country.

David A. Pfeiffer is an archivist with the Civilian Records Staff, Textual Archives Services Division, of the National Archives at College Park, who specializes in transportation records and is the author of Records Relating to North American Railroads, Reference Information Paper #91 (National Archives and Records Administration). He is a lifelong baseball fan, particularly of the old Washington Senators, and has done baseball-related research.

John Vernon has served the National Archives and Records Administration as archivist, historian, and teacher. Before coming to the Archives he served as a history professor at Tuskegee Institute, where he gradually became interested in doing research in archival records. His most recent research interests and publications have concentrated on Jackie Robinson's civil rights activities and advocacies, sports documentation issues, and the Negro Leagues.