An Archival Odyssey

The Search for Jackie Robinson

Federal Records and African American History (Summer 1997, Vol. 29, No. 2)

By John Vernon

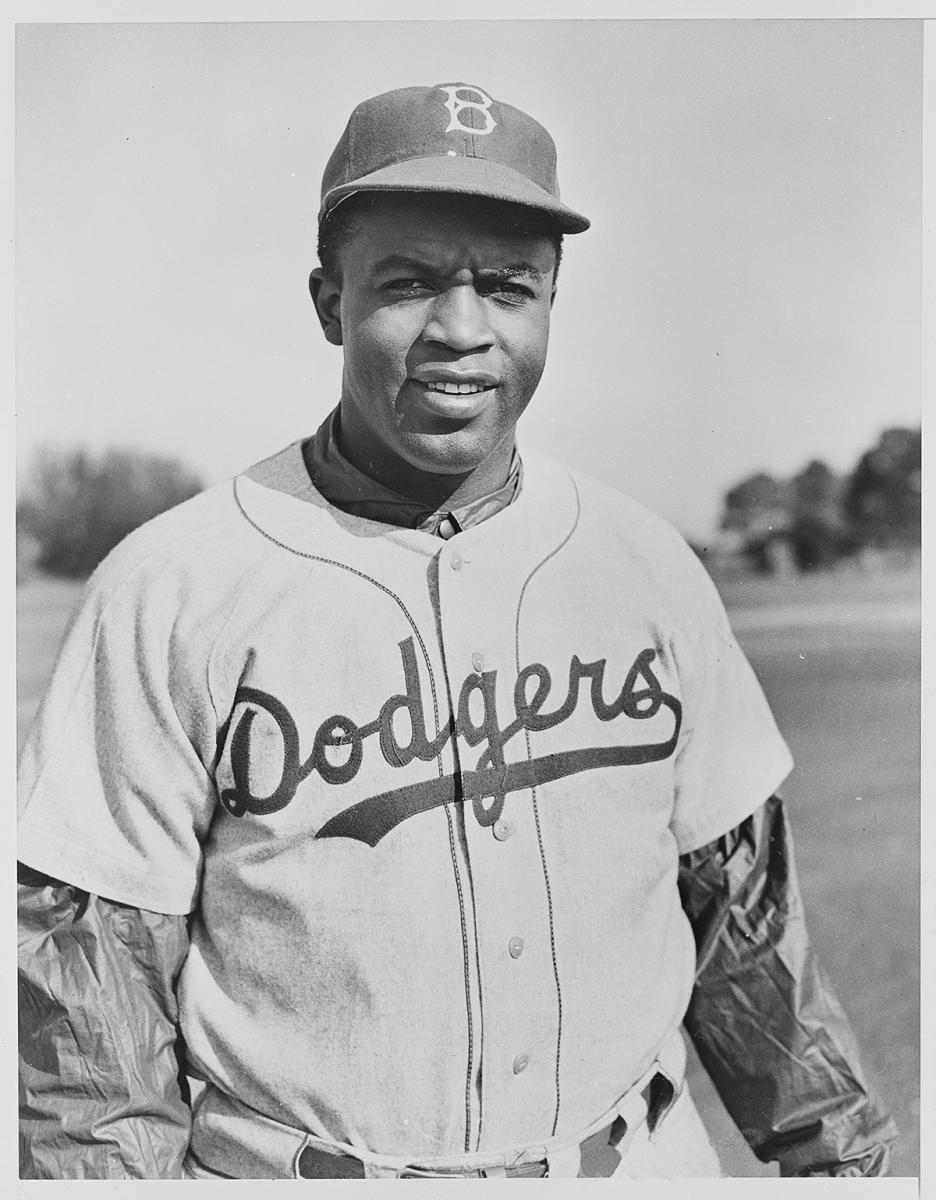

When I began the search for Jackie Robinson records among National Archives holdings several years ago, I never thought that effort would lead to a civil rights–oriented article for Prologue. I was not unaware of Jack Roosevelt Robinson's importance as luminous emblem for racial progress by virtue of becoming the first acknowledged African American to play big league baseball in the twentieth century. For Robinson the ballplayer, I fully expected to locate archival evidence regarding his stature within his profession, and I did.

But I discovered other governmental documentation as well, which reflected another side of Robinson outside baseball. These records portrayed Robinson as a public-spirited citizen who, in the years before and after his magnificent ten-year major league career (1947–1957), worked equally hard to combat institutionalized racism in the larger society beyond sports.

I started my research quest in audiovisual records, and it was well that I did, because they provided dramatic testimony to Jackie's eminence as player and public personage. Although donated Paramount, Movietone, and Universal news footage devoted heaviest attention to Robinson's on-the-field feats, there was also film attesting to his civic, political, and philanthropic interests.(1)

In 1949, probably the year of his greatest baseball achievements, the movie cameras captured Jackie's participation at three separate non-baseball occasions in New York City: the Friendship Food Train intended for Israel; his receipt of the George Washington Carver Memorial Institute Race Relations Award; and his involvement in Brotherhood Week for the National Conference of Christians and Jews. He was also filmed testifying before the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) in Washington.(2)

The news coverage of all these non-baseball events—indeed Robinson's willingness to freely take part in them—suggests that he was not content to be viewed as merely the first accomplished Negro ballplayer to be allowed equal playing status with whites. Clearly he possessed a determination to do more than play well on the field. His sense of societal obligation extended beyond ballyard confines, and the news camera furnished concrete evidence of Jackie's civic-mindedness and determination to be an instrument for the public good.

Similar visual testimony to Robinson's growing prominence is presented in National Archives photographic collections of the United States Information Agency.(3) Images taken of Robinson over more than a twenty-year period inform us of his progress through public life, first as individual athlete, family man, and team player; later as prestigious awards recipient and presenter; and still later as aging superstar become prosperous businessman. Through such materials, it can be seen that Robinson built upon his original status as trailblazer and symbol of limited racial advancement to become a fully mature and highly visible champion of black political and economic uplift. This is reflected in publicized appearances with such notables as President Dwight Eisenhower, with race leaders of the 1950s and the 1960s, well-known African nationalists visiting this country, and white liberals of the era.

After sifting through films and photographs, I felt ready to approach textual records that might illuminate the attitudes and behavior of a younger Jackie Robinson before his transformation into baseball icon. I found three military record groups especially useful in showcasing the thoughts, actions, and concerns of army 2d Lt. "Jack R. Robinson" who faced a general court-martial at Camp Hood, Texas, in August 1944 for unwillingness to honor southern racial etiquette. Pretrial depositions, issuances, correspondence, and related papers from these sources reveal a twenty-five-year-old Robinson no less resolved than later in life to challenge racial barriers to full participation in American life. This accumulation of records indicates that there were countless other black Americans who equally resisted racial discrimination against them, Robinson's voice being only one of many joined in protest.

Within Record Group (RG) 407, Records of the Adjutant General's Office, 1917–, is a rich concentration of records shedding light on divergent American attitudes toward a racially segregated military. As global warfare deepened, it became increasingly clear to the army that maintaining Jim Crow was expensive both in terms of morale and efficiency of effort. At the same time, it did not want to bring down a political firestorm by appearing to challenge or erode the racial status quo.(4) Individuals and groups from several ethnic groups and from various parts of the United States hotly debated racially polarized issues, registering their opinions with the white and black press, the War Department, the army and other armed services, and even with President Roosevelt and his wife, Eleanor.

Thus these files reflect widely conflicting views as to the proper treatment of black and other minority servicemen and women. For example, many letters written by patriotic African Americans comment witheringly on relegation of black troops to mere support roles as truck drivers, stevedores, cooks and dishwashers, and the like instead of letting them play true combat roles. At the same time, southern white congresspersons and senators were articulating passionate concerns of their own. They regarded as dangerously and hopelessly misguided the army's increasingly liberalized regulations toward black service personnel. If equal access by race to post exchanges, recreational facilities, movie theaters, and common transportation were allowed on military posts, such observers feared that blacks would expect the same treatment elsewhere. Consequently Dixie's time-honored racial mores stood endangered.

Because such countervailing values were being frequently and openly expressed, military brass was kept busy trying to anticipate the likely political fallout. A recurrent dilemma during the course of World War II was how to appear to observe traditional racial practices and still be able to provide maximum utilization of all resources.

Records of the Civilian Aide to the Secretary of War found in RG 107 focus principally on the military's racial landscape.(5) In a sense, they serve as a bridge between unit after-action histories intended chiefly to document the presence or absence of military prowess in battle and documentation of the political and racially charged climate in which largely unassimilated ethnic minorities were called upon to perform during the war.

Among the many interesting documents are letters regarding efforts to provide equitable appointments for both black military and civilian personnel, proposed and actual use of appropriately trained black officers and enlisted men, provision of recreational facilities and services, requests for transfers, promotions, court-martials of black soldiers, black and white racial attitudes, and distribution of blood plasma from blacks. Also included are press releases, radio and movie scripts, reports on both military and civilian incidents of racial unrest, and summaries of articles and editorials from black publications.

Equally revealing are files from the Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General (Army), RG 153, which chronicle serious military proceedings, many involving African Americans who ran afoul of southern racial practices.6 Records from all three of the groups mentioned are necessary to tell the whole story of Robinson's resistance to efforts by a white busdriver to make him move to the back of a bus transporting civilian and military personnel and then to racially patronizing treatment by military police authorities called in to investigate the bus incident.

Shortly before his tank unit went overseas, 2d Lieutenant Robinson was informed that he was to go on trial for various charges stemming from his refusal to abide by Jim Crow laws. As the young officer underwent what was intended to be a painfully inflicted object lesson for violating southern racial protocol, his behavior indicated that he was not unduly impressed. Relevant documents indicate that he sought to ensure that his trial would receive the attention it deserved from the world outside Camp Hood through contact with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the black press, and the civilian aide to the secretary of war, Truman Gibson. After acquittal of all charges, he left the service, but not before writing Gibson and attempting to extenuate the treatment of a fellow black officer who was now facing court-martial charges himself because he had purchased tires on the black market. Robinson's action indicated that he was not only unintimidated by his own unpleasant experience but that he would continue to speak out when he believed racism was involved.(7) Shortly thereafter, he began to play in the Negro major leagues, thus attracting attention from Brooklyn Dodger scouts. After that, of course, Jackie Robinson quickly rose to fame and became a household name.

Through archival records, one can see that the trial and the circumstances leading up to it helped to raise the young officer's political consciousness and involve him in issues that would be revisited often in later life. His period of military service thus stands as an instructive microcosm for comprehending Robinson's motivating values and his unique position later as athlete and social activist. The records pertinent to Robinson and other black soldiers provide priceless evidence not easily found elsewhere and suggest that events during this period helped set the stage for many of the civil rights initiatives of the 1950s and 1960s.

NARA repositories outside the Washington D.C., area, especially its presidential libraries throughout the country, contain useful textual records relating to interests developed after Robinson's much-publicized retirement from the Brooklyn Dodgers at the end of the 1956 season. During this post-baseball period, Jackie chose to try to assist government and private organizations in a concerted effort to batter down the walls of intolerance. It was his conviction that the nation that had made it possible for him to personally prosper could become an even stronger bulwark of democracy for others and confer the full range of political and economic blessings of liberty on all its people.

During this time, the now grey-haired and distinguished-looking Robinson raised funds for and sat on the board of the NAACP, was named National Churchman of the Year by the National Council of Churches, presided over the American Committee on Africa, and co-chaired the American-African Student Foundation, an organization promoting college educational opportunities in the United States for qualifying African youth. Eventually, he supported Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Southern Christian Leadership Conference and appeared at many of the formal civil rights rallies, beginning in 1957 with the Prayer Pilgrimage in Washington, D.C., and including the 1963 Peace March in the same city and the 1965 Selma March.

Ample archives exist to document his Senate and House committee testimony concerning African American patriotism, the need for government support for minority business enterprise, low-cost public housing, and programs for fighting juvenile crime, drug use, educational inequities, and related ills he considered attributable to racial discrimination. Separately he attempted to do battle with the presidential administrations in office between 1956 and 1972 (the year in which he died). Jackie's opinions blew hot and cold according to his perception of how well each President in office discharged his responsibilities to advance civil rights interests. Robinson insisted often that he owed allegiance only to governmental officials or politicians whom he considered absolutely correct and consistent on race matters, and no one else. Idealism may have blinded him to the political realities of that stand, i.e., that his impatience and penchant for delivering open rebuke rarely endeared him to government insiders. His fierce confidence in the moral correctness of his views made it difficult for him to appreciate anything less than across-the-board zeal for civil rights causes he espoused. The degree of good will each administration accorded him depended on how regularly and how publicly he showed gratitude in return for what officeholders considered politically risky actions.

When Robinson retired from baseball in 1956, he was as predisposed as were so many others to "like Ike," yet the now-prosperous businessman gradually became disillusioned with what he regarded as the Eisenhower administration's timidity toward the actions of lawless segregationists. Robinson argued that the new sit-in demonstrators were acting as the true upholders of the American Way—not those white supremacists who uniformly ascribed instances of black protest to "Communist" agitation. By the time of a March 1960 Howard University student press conference, Jackie was so disenchanted with Eisenhower that he was quoted as saying about the President: "He seems more interested in playing 18 holes of golf than in the rights of 18 million Negroes."(8)

With Kennedy and Johnson, he was wary at the outset, believing both men cared more about political expediency than the correctness of a particular deed. Jackie came to change his mind and duly informed each President so. Still, there were times when he felt constrained to publicly express disagreement, as when he informed LBJ in a telegram addressed to the White House: "do you really think you can fool all the people all the time?"(9) The ex-baseballer earlier labeled presidential candidate Kennedy "the fair-haired boy of the Southern segregationists" and in an anti-Kennedy campaign flyer characterized the senator as reluctant "to look you straight in the eye, when talking about Civil Rights."(10)

Initially he was high on Richard Nixon and campaigned for the Vice President in 1960 against John Kennedy after Hubert Humphrey, whom he originally supported, dropped out of the race for the Democratic Party's nomination. Yet by 1968, Jackie grew disappointed with what he viewed as Nixon's tepid stance on civil rights and chose to campaign actively against him. In April 1972 a now much-subdued Robinson wrote a Nixon White House deputy that in retrospect he believed that Presidents only engaged in "smoke screen" deceptions to trick blacks into believing that there was official support for obtaining legitimate racial aims.(11)

In conclusion, what do these documentary materials reveal or confirm about the non-baseball Robinson? Certainly that he lived life passionately and defiantly "out there" as a gladiator for what he believed in and gave his best effort in whichever arena he performed. These records preceding and following his baseball career suggest that the quiet, diplomatic, "turn the other cheek" manner adopted by Jackie in his early baseball career (1946–1949) was actually very much out of character for him. The outspoken, opinionated ballplayer who "suddenly" emerged in the 1950s was really more the "real" Jackie, who now because of successful trailblazing believed that he had more than paid his "racial dues." This defiant, blunt-spoken person seemed almost incapable of resisting controversial commentary on a wide range of subjects including his manager, teammates, other teams, and the baseball establishment. Bewildered sports writers interpreted this "new" behavior to ingratitude or perhaps a swollen ego. On the basis of the primary evidence before us in these records, however, one could argue instead that the enforced silence during the first years in baseball was in fact aberrant and that Robinson had felt stifled.

The records also indicate that beyond athlete, he proved to be an opinionated, caring citizen, one who acted upon his conviction that participative democracy required more than adherence to the status quo. According to Jackie, one of America's most notable strengths of America was its racial diversity, and if capable individuals were allowed to compete freely without false barriers, society as a whole would benefit. He counted himself as living proof of that premise.

Robinson, in trying to consider himself both "American" and "African American," was sometimes troubled by this sense of duality. Jackie did not want to surrender his own ethnic identity as the price of acceptance by mainstream America. Finally, we come to apprehend that neither Robinson's gutsiness nor his penchant for broad service was confined to the diamond on which he performed so brilliantly fifty years ago. Present-day onlookers can more broadly appreciate Jackie Robinson's baseball feats when they can put them into the larger context of a life devoted to thwarting racism. Thus, when we commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of his integrating baseball, we are commemorating not just how well he played games but also the unquenchable spirit, sense of fair play, and dedication to others that characterized his general attitude. These selected NARA records contribute not only to our knowledge regarding both a famous black American's life but also to the portentous times in which he lived.

Notes

1. Nontextual collections are housed in the National Archives at College Park, MD. Paramount, Movietone, and Universal films are found in the National Archives Collection of Donated Materials (formerly Record Group 200).

2. 200-U(niversal) N(ews)-6077-1, 200-UN-22-309, 200-P(aramount) N(ews)-8-50, 200-UN-22-267, and 200-PN-8-96, National Archives Collection of Donated Materials.

3. See "P," "PS," and "PSA" series in Records of the United States Information Agency, Record Group 306, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC (hereinafter, records in the National Archives will be cited as RG ___, NARA).

4. See records filed under War Department decimal number 291.2 ("race"), Records of the Office of the Adjutant General's Office, 1917-, RG 407, NARA.

5. Civilian Aide to the Secretary of War, ("Truman Gibson") Files, Records of the Office of the Secretary of War, RG 107, NARA.

6. Court-Martial Case Files, 1939-1953, Records of the Judge Advocate General (Army), RG 153, NARA. (Permission to use these records must be obtained from the Department of the Army.)

7. Robinson to Gibson, Sept. 30, 1944, and Gibson to Robinson, Oct. 11, 1944, Gibson Files, RG 107, NARA.

8. WNYC (Mutual Broadcasting System) Press Release, Mar. 25, 1960, p. 2, Richard Nixon Pre-Presidential Papers, National Archives and Records Administration–Pacific Region (Laguna Niguel), CA.

9. Telegram, Robinson to Lyndon Johnson, Aug. 21, 1968, Lyndon Baines Johnson Library, Austin, TX.

10. Flyer, "Why Jackie Robinson Opposes Jack Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson," n.d., Nixon Pre-Presidential Papers, NARA-Pacific Region (Laguna Niguel).

11. Jackie Robinson to Roland L. Elliot, Apr. 20, 1972, folder "Gen HU 2-1 1-1-12-12/31/72," box 20, White House Central Files, Nixon Presidential Materials Staff, College Park, MD.

Selected Bibliography

Falkner, David. Great Time Coming: The Life of Jackie Robinson from Baseball to Birmingham (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995)

Frommer, Harvey. Rickey and Robinson: The Men Who Broke Baseball's Color Barrier (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co, Inc., 1992)

Robinson, Jackie, with Alfred Duckett. I Never Had It Made (New York: G.P. Putnam, 1972)

Rowan, Carl, with Jackie Robinson. Wait Till Next Year: The Life Story of Jackie Robinson (New York: Random House, 1960)

Tygiel, Jules. Baseball's Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983)