Bureau of Indian Affairs Records: Urban Relocation

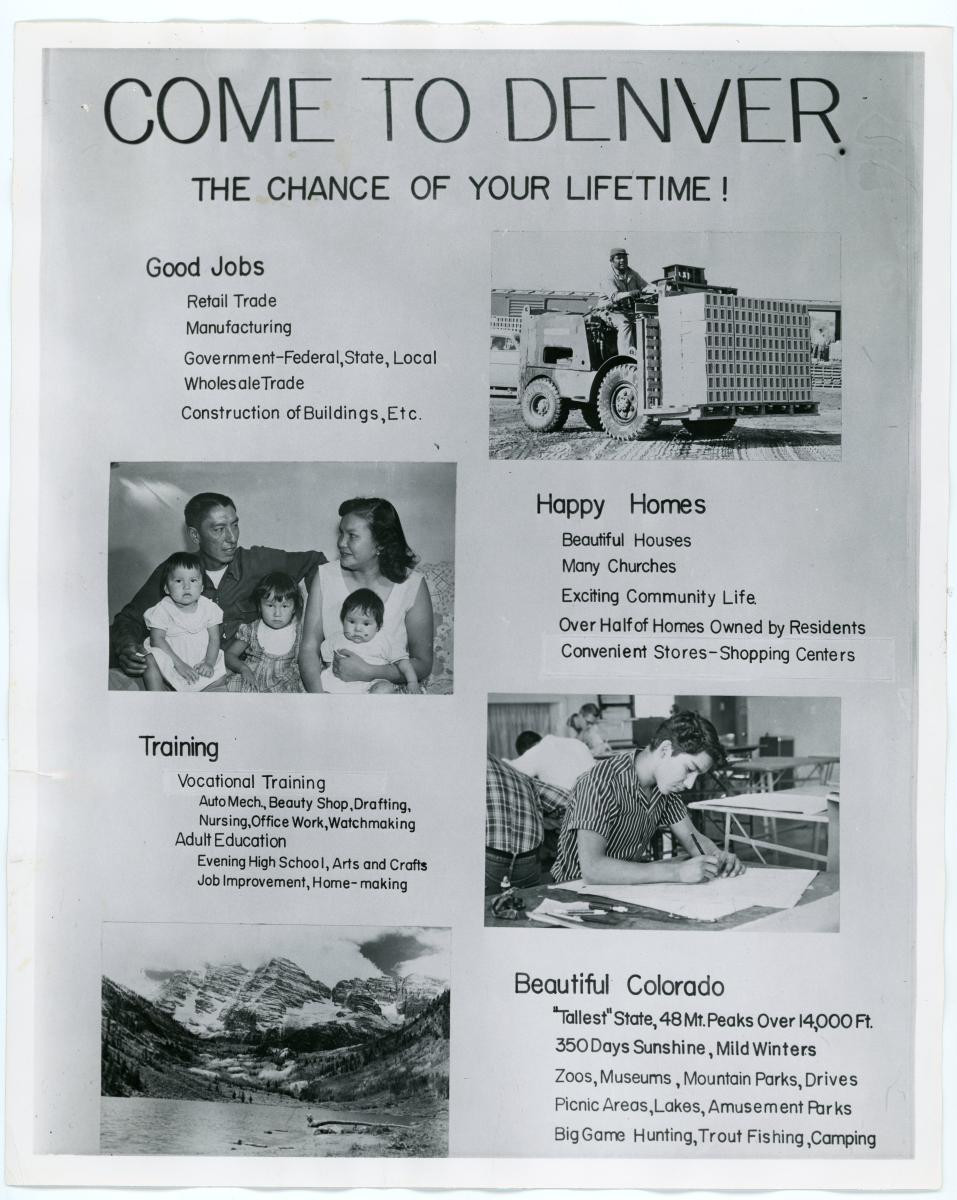

During the late 1940s and early 1950s, the U.S. Government began encouraging Native Americans to leave rural reservations and move to metropolitan areas. This push was part of the government’s policy of termination, which aimed to assimilate Native Americans into mainstream culture and end federal supervision over Native tribes.

The National Archives houses multiple series of records related to urban relocation in Record Group 75: Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA).

Historical Overview

The first Commission on Organization of the Executive Branch of the Government—more commonly known as the Hoover Commission after its chair, former President Herbert C. Hoover—recommended in 1949 that the U.S. Government seek “complete integration” of Native Americans into mainstream society by transferring administration of social programs for Native people to state and local governments, ending tax exemption for Indian lands, encouraging Native people to leave reservations for jobs elsewhere, and diminishing the activities of the BIA.[1]

In 1951, the BIA established the Branch of Placement and Relocation and set up field relocation offices in Denver, Salt Lake City, and Los Angeles to help Native people from rural reservations find employment in major cities. Additional relocation centers were added in St. Louis, San Francisco, Dallas, Minneapolis, and other urban areas in later years.[2] In fiscal year 1953, the BIA reported placing over 2,600 individuals in permanent jobs through the efforts of its relocation centers; this number grew to over 3,400 by fiscal year 1955 and to over 6,900 by fiscal year 1957.[3]

However, the push for Native people to leave reservations and relocate to urban areas had profound effects on Native communities. Many Native people who relocated under the BIA’s program faced discrimination, unemployment or low-paying jobs, and loss of traditional cultural supports in urban areas. Moreover, as the BIA only paid for one-way trips to urban areas, Native people who faced these challenges often could not afford to return home.[4]

Public Law 959, better known as the Indian Relocation Act of 1956, authorized the Department of the Interior to undertake a vocational training program for Native Americans living on or near reservations, ostensibly to improve their prospects for employment.[5] But this did little to address the underlying problems with relocation and the hardships that Native people faced because of it. Consequently, Native activists protested and organized against relocation and termination. In 1968, for example, Ojibwe activists Dennis Banks, Clyde Bellecourt, and George Mitchell cofounded the American Indian Movement (AIM) in Minneapolis to address the needs of urban Indians. AIM’s focus soon broadened to tribal sovereignty, treaty rights, reclamation of tribal land, and government corruption, among other issues.[6]

Records Overview

BIA records related to urban relocation are located at different National Archives research facilities, depending on the BIA office that maintained the records. Examples are listed below.

Select the National Archives Identifiers for the full archival records descriptions in the National Archives Catalog. For questions related to the records, please contact the custodial unit indicated.

For more information about BIA records, see Navigating Record Group 75. For additional records related to urban relocation, search the National Archives Catalog by record group number (“75”) and keyword (e.g., “employment assistance,” “relocation").

Branch of Employment Assistance (Headquarters)

Contact the Archives 1 Reference Branch in Washington, DC, for more information.

- “Records Relating to Employment Assistance Programs, 1949–1973” (National Archives Identifier: 2194626)

- “Financial Program Records, 1953–1959” (National Archives Identifier: 2194643)

- “Audit Reports on Field Offices, 1957–1959” (National Archives Identifier: 2194641)

- “Reports and Related Records, 1960–1971” (National Archives Identifier: 2194631)

- “Annual Reports, ca. 1964–ca. 1969” (National Archives Identifier: 300297)

Branch of Relocation Services (Headquarters)

Contact the Archives 1 Reference Branch in Washington, DC, for more information.

- “Placement and Statistical Reports, 1949–1954” (National Archives Identifier: 2194619)

- “Office Files, 1949–1961” (National Archives Identifier: 2194613)

- “Financial Assistance Reports Relating to Relocatees, 1951–1956” (National Archives Identifier: 2194625)

- “Relocatee Cards, ca. 1958–1959” (National Archives Identifier: 2194622)

- “Weekly Reports of Relocations and Applications in Process, 1958–1961” (National Archives Identifier: 2194612)

Anadarko Area Office. Office of the Area Relocation Specialist

Contact the National Archives at Fort Worth for more information.

- “Reports on Relocated Indians, 1952–1960” (National Archives Identifier: 641461)

Billings Area Office

Contact the National Archives at Denver for more information.

- “Adult Vocational Training and Relocation Case Files, 1955–1964” (National Archives Identifier: 2641425)

Chicago Field Employment Assistance Office

Contact the National Archives at Chicago for more information.

- “Reports on Employment Assistance, December 1951–June 1958” (National Archives Identifier: 3514914)

Denver Field Employment Assistance Office

Contact the National Archives at Denver for more information.

- “Administrative Files, 1954–1971” (National Archives Identifier: 311080799)

Gallup Area Office

Contact the National Archives at Denver for more information.

- “Records of Disbursements and Control Registers, 1958–1964” (National Archives Identifier: 2663333)

Gallup Area Office. Chinle Subagency

Contact the National Archives at Riverside for more information.

- “Subject Files of the Assistant Placement Officer, 1949–1962” (National Archives Identifier: 295116)

Juneau Area Office

Contact the National Archives at Seattle for more information.

- “Administrative Files Relating to Employment Assistance, 1957–1971” (National Archives Identifier: 628668)

Los Angeles Field Relocation Office

Contact the National Archives at Riverside for more information.

- “Central Classified Files, 1952–1971” (National Archives Identifier: 561656)

Minneapolis Area Office

Contact the National Archives at Kansas City for more information.

- “Records Relating to Relocation Services, 1957–1962” (National Archives Identifier: 60468243)

Muskogee Area Office

Contact the National Archives at Fort Worth for more information.

- “Records of the Area Relocation Specialist, 1959–1961” (National Archives Identifier: 855529)

Portland Area Office. Relocation and Employment Assistance Branch

Contact the National Archives at Seattle for more information.

- “Administrative Records of the Relocation and Employment Assistance Branch, 1958–1966” (National Archives Identifier: 1280604)

San Francisco Field Employment Assistance Office

Contact the National Archives at San Francisco for more information.

- “Reports and Correspondence, 1954–1963” (National Archives Identifier: 62842579)

Related Records

Additional information about the BIA’s relocation activities may be found in BIA Correspondence Files.

Notes

[1] See Commission on Organization of the Executive Branch of the Government (Hoover Commission), “Report of Commission on Organization of Executive Branch on Social Security, Education, and Indian Affairs,” House Document No. 129, 81st Cong., 1st Sess. (1949), quoted at p. 65. For more information about the Hoover Commission, see “Records of the Commissions on Organization of the Executive Branch of the Government [Hoover Commissions],” Guide to Federal Records, https://www.archives.gov/research/guide-fed-records/groups/264.html (accessed October 11, 2023).

[2] Edward Hill, comp., Preliminary Inventory of the Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Volume 2 (Record Group 75) (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Service, 1965, updated 2007), p. 94.

[3] See “Bureau of Indian Affairs,” in Annual Report of the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1953 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1953), p. 39, available online through HathiTrust: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015031655114&seq=547 (accessed October 11, 2023); “Bureau of Indian Affairs,” in Annual Report of the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1955 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1955), p. 246, available online through HathiTrust: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015031655106&seq=302 (accessed October 11, 2023); and “Bureau of Indian Affairs,” in Annual Report of the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 3, 1958 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1958), p. 220, available online through HathiTrust: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015031655106&seq=1968 (accessed October 11, 2023).

[4] National Archives and Records Administration, “American Indian Urban Relocation,” last updated March 3, 2023, https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/indian-relocation.html (accessed October 4, 2023).

[5] “An Act relative to employment for certain adult Indians on or near Indian reservations” (Public Law 959), 70 Stat. 986, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-70/pdf/STATUTE-70-Pg986.pdf (accessed October 4, 2023).

[6] Minnesota Historical Society, “American Indian Movement (AIM): Overview,” last updated October 9, 2023, https://libguides.mnhs.org/aim (accessed October 12, 2023).