Hidden Treasure

Uncovering Panoramic Photographs of Alaska

Summer 2017, Vol. 49, No. 2

By Kerri Lawrence

The mission of preservation teams at the National Archives is always the same: preserve important documents, images, and videos of our nation’s history to provide access for people throughout the world. Every so often, however, a preservation project uncovers a hidden treasure and a new story—a story that may have otherwise gone untold.

When the National Archives preservation team embarked on reformatting and duplicating approximately 52,000 original nitrate-based negatives of Alaska onto safer film, it was assumed that the images were taken by topographers and surveyors to collect data in order to map the Alaskan territory.

These images, from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) from 1910 to 1932, captured the vast expanse of the Alaskan landscape, including some 360-degree views that depict the natural resources–rich land of what became the nation’s 49th state.

How those images were discovered and brought to the public is a tale of archival detective work and dedicated preservation efforts.

Thanks to one team member’s curiosity, dedication, intrepid research, and photography skills, some treasures were found hidden among those previously unseen images of the vast Alaskan landscape.

A Preservation Project and a Discovery

Richard Schneider, a special projects management and program analyst, joined the preservation effort in 2008, one year after the National Archives took custody of the USGS images. The project involved nitrate film, which can be highly combustible, if not stored properly, and which poses safety concerns, if not handled correctly. Originals were kept in fireproof metal containers in a refrigerated room and monitored to minimize the risk of internal combustion or danger to staff.

“Surprisingly most of these negatives were actually in fairly good condition,” Schneider said. “They showed minimal damage, which was likely due to water exposure, not nitrate deterioration. When unsleeved negatives get wet and then dry out, they can stick together. As a result, hundreds of images were unable to be duplicated.”

However, thousands of other images were still viable. Schneider’s role in the project was to organize the images for duplication. He employed systematic methods, ensuring the images were aligned in the same direction, with the sky at the top, mountains on the bottom, and emulsions facing down.

It was through this systematic organization of the images that he noticed the same mountain in two different places on two different images. That caused him to examine the images side by side and then align them with each other.

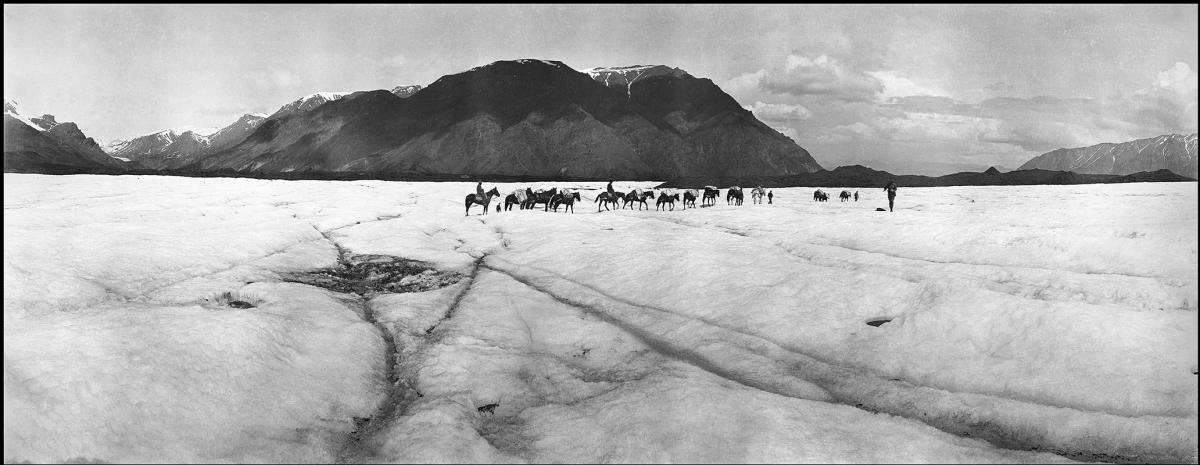

“Much to my surprise, the images aligned to create some incredible 360-degree views of the Alaskan territory,” Schneider said. “It was like having pieces of a puzzle, and when I put the pieces together, they formed a beautiful panorama.”

Capturing the Work Life In Alaska’s Wilderness

Schneider said this was his “aha moment” during his preservation work.

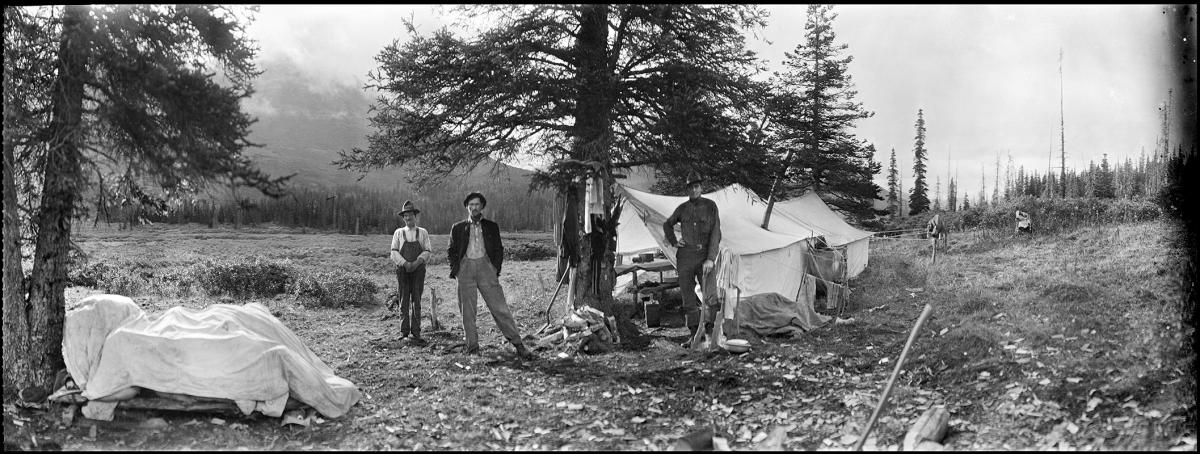

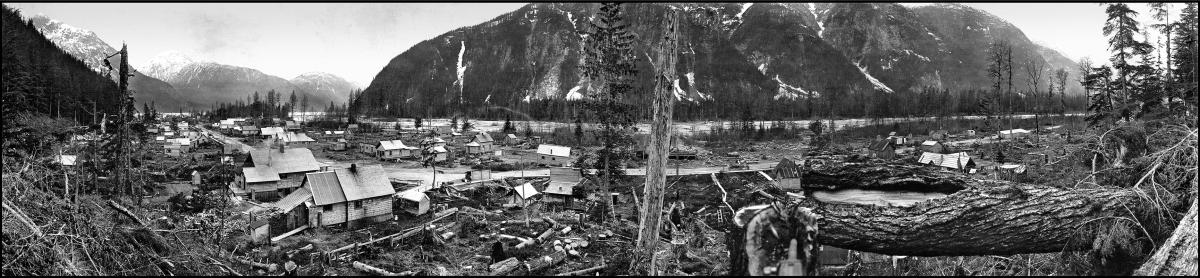

“That made the project truly blossom for me,” Schneider said. “It was the discovery that, mixed in with the data-capture photographs, were these aesthetic gems that captured work life in the Alaskan wilderness, photography and surveying techniques, and many noteworthy towns and geological formations.”

Schneider began scanning images, about 120 in all, as time permitted.

“I chose those images that I personally found visually appealing and stored them on my computer for possible later use,” he said. “I had diamonds in the rough on my computer. Every so often, I would look at them. When I discovered that several photos could be put together to form a panorama, it was a great surprise. It kept me going.”

Schneider said he hooked up several of the 5-inch-by-12-inch negatives together. He said his discovery also sparked his curiosity about the original purpose of the images themselves.

“At the start of the project, nobody truly knew the purpose of the films and photos,” Schneider said.

“What I found out from some independent research on them was that the visually uninteresting photos were actually what the photographers sought to capture,” he said. “These images, taken from 1910 to 1932, were used for data gathering—for mapping the Alaskan territory. And there was a lot of area to cover.”

An Innovative Approach to Mapping the Countryside

Through further investigative research, Schneider discovered James W. Bagley’s original publication, USGS Bulletin 657, The Use of the Panoramic Camera in Topographic Surveying (1917), which outlined the purpose of the original photographs. “The technical information, evidence, and justification, as well as the advanced mathematical formulas used within this document make it one of the most salient publications ever produced on the scientific uses of the panorama,” Schneider said.

“Bulletin 657 explained how Bagley, a topographer who was relatively unknown outside the USGS, used a panoramic camera to capture images of the Alaskan countryside versus the tried and true method of relying on the sole use of the plane table and alidade,” Schneider said.

“Most of the data gathering work was done in the field throughout the continental United States. Using a plane table and alidade, the topographers would draw out the topography, capturing geologic features integral to map-making, onsite,” he said.

“In Alaska, with the use of panoramic photos, topographers could now capture the images of much more expansive areas, then take them back to their offices to do the drawing, allowing for more time, more precision of mapping, more detailed maps, and less time required in the field.”

Schneider noted that this was an innovative approach to data collection and mapping.

“They would set up predetermined stations from scouting parties, take photos, and move on,” he said. “They had to process and shoot the film in the field, verify that they got what they wanted as it wasn’t simple to go back to these areas, and then printed the photos back in D.C.”

The investigation also uncovered another piece of the puzzle.

“The topographers often shot test rolls in the field; Most of the test photos were scenic shots or group shots,” he said. “Those photographs ultimately formed the most visually interesting and aesthetically pleasing photographs.” These were the photographs Schneider had discovered during the National Archives’ duplication project.

Schneider’s Research Uncovers Back Story of Aerial Images

Schneider’s initial research on the origin of the photographs prompted him to continue learning about Bagley, uncovering another very interesting part of the story.

“Bagley was a pioneer of using aerial photos for mapping,” Schneider said. “He developed a panoramic camera used to document the topography and geology of Alaska. Bagley was simply the most prolific, influential, and technically astute photographer the USGS had in these remote locations,” he added.

“After his work with the USGS, Bagley joined the Army in 1917, went to France, and participated in the Great War, where he put his photographic and topographic skills and knowledge into practice,” Schneider stated. “He was a pioneer of using aerial photography to map enemy entrenchments and gun emplacements.”

Schneider added that “Flying itself was relatively new, and Bagley actually thought of taking photos from the sky to help the war effort.” Schneider noted that Bagley developed a tri-lens camera, which is now in the Smithsonian Institution’s Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. “The three-lens camera could photograph a much larger area in a single flight than a single-lens camera could. The images were then used to overprint enemy trenches and gun emplacements over existing maps for precision targeting.”

Bagley retired from the Army as a lieutenant colonel in 1936 and went on to become a lecturer at the Institute for Geographical Exploration at Harvard University, writing several articles and a book on aerial surveying and aerial photography. He died in 1947.

Schneider said he truly felt a connection to Bagley and his life’s work.

A Personal Connection as a Ship’s Photographer

Initially, Schneider was invited to participate in the National Archives’ preservation project based on his interest in Alaska and his own panoramic photography experience. He had previously created “The Long View” exhibit at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, which was an assortment of panoramic photographs from still picture holdings.

“‘The Long View’ exhibit was a sampling of panoramic photographs from still pictures that included a sampling of holdings from the National Archives’ cartographic records,” he said.

Schneider has an abiding interest in geography, photography—specifically panoramas—and Alaska itself. He remembers his affinity for geography started in the fifth grade, when he drew a large map of Earth on a classroom bulletin board.

Fast forward to 1985, Schneider took on a job as the ship’s photographer on the Sun Princess, a cruise ship made famous by the television show The Love Boat. In May 1985, he began the Alaska touring season, traveling from Vancouver to southeast Alaska, some of the same ports captured in the panoramic photographs he was now helping to preserve and duplicate.

“The project had a huge personal connection for me. My professional experiences in Alaska allowed me to see and photograph the beautiful Alaskan countryside,” he said. “While I was there, I developed an affinity for panoramic photos, which I had studied only briefly in my college career. I discovered a local artist, who I became great friends with, who helped to instill my love for panoramic photos, and who helped to develop my skills in panoramic photography. Alaska has some of the most beautiful scenery on this Earth.”

The “Hidden Treasure” Exhibit on Indefinite Display

“This preservation effort was significant. We helped to preserve information that may not have ever been known prior to this project. And in the process, we found some treasures,” Schneider said. Duplicates are in the National Archives’ still picture holdings, and the preservation project is complete.

Eight years in the making, Schneider crafted an exhibit based on the preservation project to share his research and work. Titled “Hidden Treasure: Panoramas of the Alaskan Frontier,” the exhibit debuted on December 23, 2016, and is on indefinite display at the National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

The “Hidden Treasure” exhibit dramatically depicts the beauty of Alaska, using the extraordinary USGS images—a sampling of more than 6,000 panoramic photographs from the collection. All of the photographs in “Hidden Treasure” were scanned from the original negatives, and many were digitally combined into long panoramas that encompassed up to a 360-degree view. The “Hidden Treasure” display features 36 framed panoramas, eight panoramas incorporated into information panels, and seven maps of the Alaska Territory from the National Archives’ cartography holdings.

Schneider said that he “found great satisfaction in connecting our photo records to other documents. That’s what is so amazing about the National Archives’ holdings . . . we have so many things that connect to paint a more thorough picture of a place, event, or even a person. It’s what makes National Archives’ holdings so special and, often, so invaluable and unique.”

Learn more about . . .

- The Alaskan frontier in panorama

- “‘Hidden Treasure’: Panoramic Photographs of Alaska Territory”

- Alaska records and the digitization project at the National Archives at Seattle