Citizen Archivists Energize Civil War Digitization Project

Summer 2016, Vol. 48, No. 2

By Jacqueline M. Budell

The recent discovery of a Walt Whitman–scribed letter for a sick soldier—and the discovery of many other treasures no less important—are possible at the National Archives often because of the work of citizen archivists.

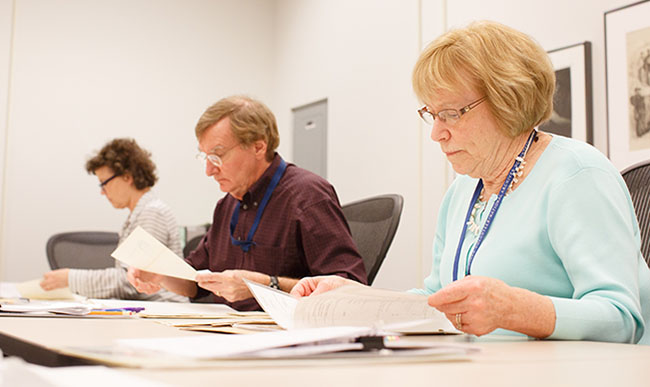

These volunteers receive extensive archival training and work alongside staff as part of the project team. It's a collaborative relationship in which knowledge meets enthusiasm—allowing progress on large-scale digitization projects despite limited internal resources.

The Civil War Widows' Pension Digitization Project in Washington, D.C., was launched in 2005 with a small group of volunteers meeting weekly to prepare the case files for digital imaging.

This record series (known as the Widows' Certificate files, or WCs) contains 1.28 million case files and occupies two football-field-sized floors in the downtown Washington building. The series also includes the approved application files for minor children, parents, and siblings of deceased soldiers starting with service in the Civil War.

The WC series is one of the most requested in National Archives holdings due to the rich family information contained in the files.

For example, widows of soldiers were required to submit evidence of the legality of their marriage and prove the names and ages of their children under the age of 16. Pension files therefore contain marriage and birth records that are either official (from an institution) or unofficial (such as affidavits from witnesses to these events).

Evidence of a soldier's military service and death was also required, and the Adjutant General's Office of the War Department was kept very busy consulting muster rolls to confirm this information for each application.

Citizen archivists on the project identify and arrange all the key evidence in each case file to allow researchers to better pinpoint a soldier and applicant(s) of interest, sometimes pondering the inclusion of something unusual in the file like a soldier's letter.

Why was the hospital letter penned by Whitman from Robert N. Jabo to his wife Adeline submitted as evidence?

Jabo died after his discharge from service, so military records do not show evidence of his death. For Adeline to receive a pension under the act of July 14, 1862, the burden of proof was hers. Thus, the pension examiner requested additional information regarding Jabo's physical condition in the months directly following his discharge.

Adeline submitted her husband's personal letter as evidence of his illness during that time since he wrote that his "complaint is an affection of the lungs." Personal items became "evidence" when sent to the federal government in support of pension claims and so remain with the case files.

It took two applications, a rejection, additional witness affidavits, and a second review of the case in light of new and more lenient pension legislation before Adeline was finally added to the pension roll in 1875, more than seven years after she first applied.

All this correspondence and evidence can amount to a significant number of pages. The WC case files range in size from perhaps 10 pages to many hundreds and can take from 20 minutes to several hours to prepare before conservation treatment and imaging can take place. Having a skilled team of citizen archivists review the files well in advance of this other work affords the time needed for a careful page-by-page review as opposed to a blind mass digitization approach.

Their work also consists of stabilizing fragile documents and identifying those that need further conservation treatment to ensure safe handling and the complete capture of all unique information at the camera.

For example, 19th-century glue holding related pages together may obscure text, and National Archives conservators can safely separate the documents so that information underneath is visible to researchers. Conservation training is essential to making informed decisions in this assessment of each file.

Finally, citizen archivists use their training in Civil War army organization and 19th-century handwriting to abstract key information for an online index that allows the collection to be searchable and browseable. The indexed information is extremely valuable because researchers with varied objectives search the collection in different ways (for example, by name versus military unit), and because the original records are arranged by pension certificate number—not by name.

Future generations of researchers will benefit from the dedication of this skilled citizen project team.

Current researchers already are, most notably Jabo's great-great grandson, Lemie Gibeau of Springfield, Massachusetts. Lemie's father, Louis Gibeau, was the only offspring to legally revert back to the French Canadian spelling of the family surname.

The soldier's widow and children spelled their surname "Gebo." Census records show that Jabo's son Joseph moved his mother with him to Clinton, Worcester County, Massachusetts, sometime between 1895 and 1900. Adeline died there in 1901.

Lemie and his wife, Fern, have been researching the family's history for decades and long wondered about the soldier's fate. They had studied Jabo's military service records but had not discovered the widow’s pension file that contained the Whitman-scribed letter and documented Jabo's death. Multiple pension files containing Jabo's unsuccessful applications for a soldier's pension and Adeline's successful widow's application had not been consolidated into one file by the pension office, which was the usual practice.

This was likely due to the different aliases of Jabo's name—the first soldier's application was indexed under the name Robert Jabo (no initial), the second under the name Nelson Jabo, and his widow's pension file under the name Robert N. Jabo. Making this connection allowed Jabo's full story to be revealed and the Gibeau family to finally learn how and where the soldier died.

The Gibeaus said they were suspicious when a reporter approached them in March with news of the Whitman discovery in connection with their Civil War ancestor.

"We had no reason to believe it at first based on our research years earlier," Fern explained. National Archives staff soon confirmed the connection between the documents and their family.

Lemie said he is "thrilled" to know that his great-great grandfather spent time with an iconic figure in American history, and he has shared the news with relatives living coast to coast.

Certainly, Whitman scholars regard the Jabo letter as a vital contribution to their understanding of Whitman's time spent with soldiers. At the same time, Lemie and his family view the document in a very personal way—it is a gateway into their ancestor's emotions and mind-set. It gives them access to a key moment in their ancestor's life, and it clarifies what had been misunderstood. Before this discovery, they imagined Jabo had simply abandoned his family in New York and chose to stay in Washington. Now they know that Jabo longed to see his family again, and they feel the sadness of his lonely death.

The volunteers on this project regard the treasures they find, both personal to one family and the rare ones of historical significance, to be of equal importance. They support the National Archives' mission to create global digital access to the records while ensuring the long-term preservation of these fragile paper documents.

This digital project has begun to accomplish what was considered unimaginable just 10 years ago: easy digital access to a large body of highly valuable primary source material that will open new avenues of study and make possible both genealogical discoveries and new historical conclusions.

Preparing 19th-century records for indexing and digitization is extremely detailed work that requires great discipline, skill, and much time. The National Archives' citizen archivist team meets this challenge with enthusiasm and an incredible willingness to do the job not just well, but exceptionally well. And it was this dedication to detail that brought to light a very special discovery when volunteer Catherine C. Wilson spied a small postscript at the end of a soldier's letter home that included the name Walt Whitman.