Murder! Orphans! Escape!

A Little-Known Story Uncovered in the Files of the American Consulate at Kunming, China

Spring 2016, Vol. 48, No. 1

By Cynthia Peterman

© 2016 by Cynthia Peterman

For years before Pearl Harbor brought the United States into a war in the Pacific, the Republic of China battled invading Imperial Japanese forces seeking to extend their political control and economic influence.

The Second Sino-Japanese War, with roots in Japan’s occupation of Manchuria in 1931 and its desire for access to natural resources, began in earnest in 1937 and continued through the end of World War II. The war resulted in enormous losses on both sides, with casualties at more than 50 percent of all losses in the Pacific.

In 1940, Chanyi (today Zhanyi) in the southern Chinese province of Yunnan was in the flight path of Japanese war planes supporting ground forces in northern French Indochina. The Japanese wanted to cut off China’s arms supply via the Sino-Vietnamese Railway from Haiphong through Hanoi to Kunming.

Yunnan, one of China’s 18 provinces, was very isolated and rural with a large ethnic minority population and the largest non-Chinese speaking population in all of China. Christian missionaries had for some time played an important role in providing an education to the Chinese. The missionaries were attracted to Yunnan by the opportunity to evangelize the local Chinese, despite the dangers of living in such a remote area.

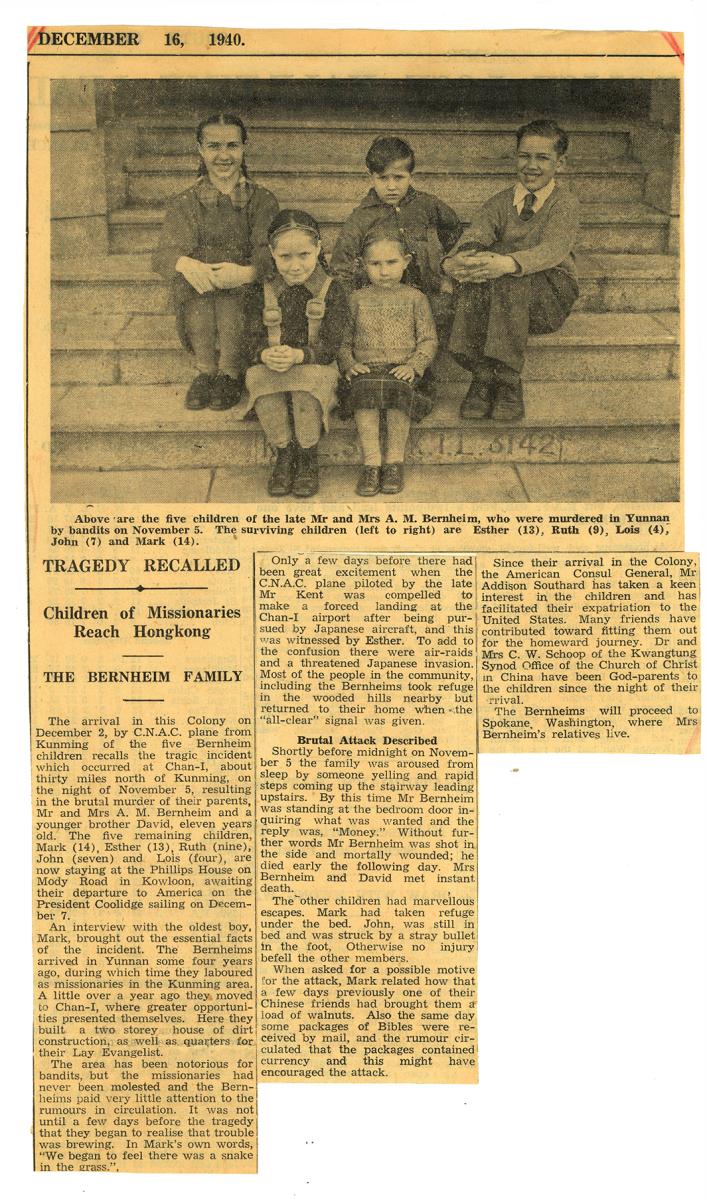

The Bernheims—an American missionary family—arrived in Chanyi from their Spokane, Washington, home in 1936, just one year before the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War. Although local officials urged them to leave in October 1940, they were reluctant to return to the United States and stayed, instead, to continue educating and proselytizing the population. One month later, Pastor Alfred Max Bernheim, his wife Emily, and their 11-year-old son David were dead, leaving five orphaned children.

A Tragedy in Remotest China Told in Records at Archives

The Bernheim family’s story comes from the records of Foreign Service posts, in a section on deaths reported to the U.S. consulate. The report contains nearly 200 documents about this family alone, mainly letters and telegrams exchanged between Troy Perkins, the consul general; Deaconess Julia Clark, another American missionary in residence at Kutsing (today Qujing); and various Chinese and American officials between November and December 1940.

The American consulate in Yunnan was located in the provincial capital of Kunming, some 105 miles from the Bernheim base in Chanyi. John Stewart Service, the vice consul from 1933 to 1941, described the province: “Yunnanfu was considered the end of everything, I mean to hell and gone, a remote and isolated post in southwest China.”

Banditry was common in the area around Chanyi. Sometimes gangs as large as 50 or more attacked homes and businesses.

Japanese air raids also became more frequent in autumn 1940. In a letter the Bernheims wrote to their church in Spokane, the family reported:

The railroad has been destroyed. All foreigners are leaving the mission stations. If evacuation becomes necessary, there will be a three months’ journey by horse to the edge of Burma, if horses can be secured; if they cannot, we will have to walk. Of course, we are not making any predictions, but just looking to God day by day. The children have their pack sacks all ready, so that if war comes heavy over our heads, we will be ready to go to the hills. All roads are broken and cut off in this section of the country.

The Three Murders and a Plea for Help

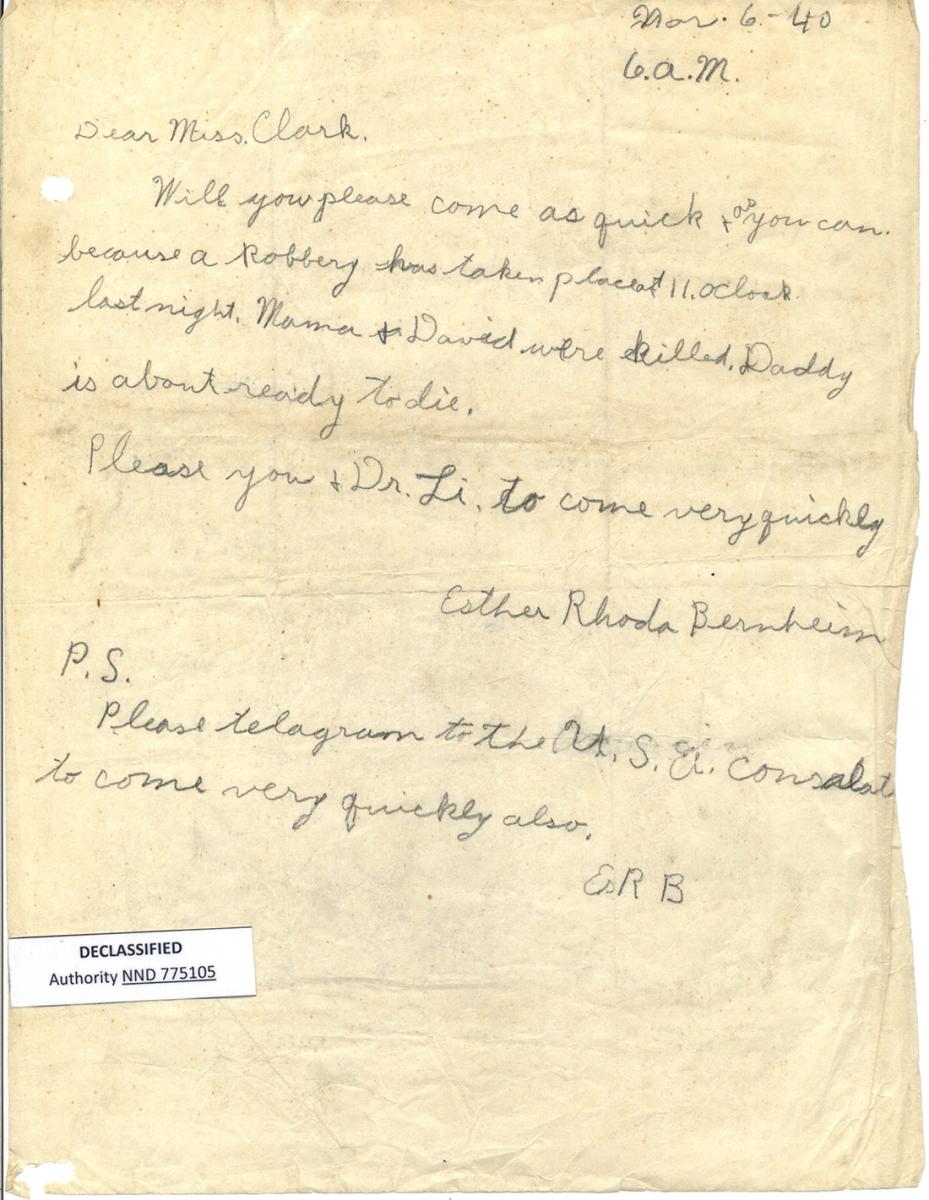

At 6 a.m. on November 6, 1940, 13-year- old Esther Rhoda Bernheim wrote a note to Clark:

Dear Miss Clark

Will you please come as quick as you can because a Robbery has taken place at 11 o’clock last night. Mama & David were killed. Daddy is about ready to die. Please you & Dr. Li to come very quickly.

Esther Rhoda Bernheim

P.S. Please telagram [sic] to the U.S.A. consalate [sic] to come very quickly also. Es.R.B.

The day before the murders was a normal day for the Bernheim family. Mrs. Bernheim and the children had gone out fishing in the countryside and returned about 3 p.m. Before supper, Mrs. Bernheim, who was expecting another child in April, taught English to a Chinese student. The entire family went to bed at 8 p.m. At 11:30 p.m. there was a pounding on the back door, footsteps running up the staircase, then shots.

At the nearby radio station, a sentry saw a large group of some 40 to 60 people mov- ing around. Frightened, he went back in and locked the door. Members of the gang pounded on the door in an effort to break in.

The sentry telephoned headquarters for help, believing the bandits wanted to rob the station.

When help arrived, shots were exchanged. Liu Kai, commanding officer of the Fourth Aviation Headquarters, later reported, “We chased the bandits for some distance, and finding our Station unmolested we stopped the pursuit as our business was not concerned with mopping up bandits.”

Bandits Claim Murder Not Their Aim in Raid

The gang of some 60 bandits that attacked the Bernheims did not seem to know that the family was a religious group. During interrogation, the leader admitted to the robbery, saying that they had seen Reverend Bernheim on more than one occasion carrying a case out of the house. The Bernheims would carry “big bundles and suitcases” whenever they fled the city during air raids. The district magistrate said that he had asked the family to move away from the compound due to air attacks, but they refused. During the robbery, the bandits were surprised to find that the case contained only books and religious literature.

The bandit leader said that murder was not their plan, but the attack instantly took the lives of Mrs. Bernheim and her son David. Reverend Bernheim died of his wounds two days later. Seven-year-old John was lying in his mother’s bed when he was shot in the heel of his foot.

Following the attacks, the consulate dispatched two representatives to meet with Clark and the surviving children at Clark’s mission in Kutsing. Stanley McGeary, a clerk at the American consulate, wrote:

We’re all set to leave by Navy truck in the morning at seven. When I called on Mr. Chow he had a truck chauffeur, policeman and gasoline for the trip both ways. . . . He is holding the truck chauffeur, policeman and gasoline for our use until 8:30 a.m. tomorrow in case there is a slip up with the Navy truck. So we are bound to be off, I’m sure. Mr. Chow certainly went ‘the second mile’ in providing gasoline.

It took the two Americans two days by truck to drive the 71 miles to Kutsing from Kunming.

Five Orphaned Children Receive Aid to Go Home

Chanyi’s remote location and the difficulties presented by the war meant that there was little help for burying the victims. Clark wrote to Consul Perkins on November 8: “after wiring you I sent for coffins and to prepare the graves in our Christian cemetery, and then played undertaker, preparing the bodies. . . . We did manage to make them look well enough so I could let the two older children see them in the coffin.”

The parents had left no will and no real assets, so Clark was given permission to auction the property to raise money for the children’s care. The American embassy in Hong Kong approved funds for transportation, various missionary groups took care of purchasing new clothing, and the hospital in Kutsing took care of the medical bills. The children would stay in the Kowloon area of Hong Kong for a few weeks in order to allow them to adjust to “more normal ways of living,” as Clark put it.

The children, ranging in age from 4 to 14, arrived unaccompanied in Hong Kong on December 5, 1940. They sailed on the steamship President Coolidge, departing Hong Kong on December 25 for San Francisco.

The Bernheim passport was now in the hands of Mark Noah, the eldest child. On January 18, 1941, the Associated Press reported the children’s arrival in San Francisco as they were met by their aunts Lydia Hollandsworth of Spokane and Florence Howell of Tacoma, Washington. The passengers aboard the ship had donated several hundred dollars to the orphans.

Murders Strain U.S., China Ties

The murders of the three Americans had the potential to create diplomatic friction between China and the United States. The United States had tried to stay neutral since the 1937 outbreak of war between China and Japan. But after Japan rescinded its trade treaty with the United States in January 1940, America was able to send unrestricted military supplies to China. In September Japan signed a treaty with Germany and Italy, linking the conflict in Europe to the war in Asia.

On November 7, Consul Perkins sent a letter to the Special Yunnan Delegate to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Wang Tchang Ki:

I scarcely need to point out the unfortunate effect that this brutal matter will have on many people in the United States; it is believed that swift and effective measures to apprehend and punish the responsible persons would do much to allay this feeling.

Perkins reported to the American embassy in Chungking on November 8 that “By the Special Delegate’s own admission the Chanyi magistrate has failed in his duty as he did not give the Bernheims the protection directed by instructions issued early in October.

The headline of a November 12, 1940, news clipping of unknown origin proclaimed, “Chungking Expresses Regrets to U.S.” The article reported that the “Chinese Government yesterday expressed deep regrets to the United States over the murder of an American missionary and two members of his family. . . . State Department officials said they were awaiting further information regarding the death of the three Americans before deciding on any further action” The murders made news back in the United States when the New York Times carried two stories about the incident: “Americans Slain in China: Robbers Kill 2 and Wound 2 of Spokane Missionary Family” and “Bandit Gang Pursued: Chinese Offer Rewards for the Killers of 3 Americans.”

American officials exerted pressure on Chinese provincial authorities to apprehend and prosecute the robbers. Within one month, the Chanyi magistrate informed the American consulate that the culprits had been apprehended.

Epilogue

The five surviving Bernheim children moved in with Lydia and Rev. Charles Hollandsworth along with their two sons in Spokane. In their published reminiscences, all expressed great gratitude to their aunt and uncle for taking them in at such a critical time in their lives. Most of the children grew up deeply religious and stayed in Oregon and Washington.

Esther, the oldest daughter, married a minister, and the two of them worked in Oregon churches before moving to the Philippines in 1956 with their two sons. They lived there for many years, raising two more sons, before Esther’s death in 2008.

Ruth, the middle daughter, worked and married a man from San Jose, California, where they lived until they retired to Salem, Oregon.

Lois, the youngest daughter, who was born in China, married a career military man and had two sons.

Mark, the oldest son, joined the Army, married, and became a licensed minister. He was pastor for churches in Oregon and Washington before his death in 1976. His wife, Betty, took over the role of pastor, and their daughter Becky followed both mother and father in this role.

John, the youngest son, went to college in Oregon and became first a teacher, then a counselor. He remarried after the death of his first wife and had three daughters.

The story of the Bernheim family illustrates the many fascinating treasures found in National Archives records. Yet, despite abundant letters, telegrams, and official records, there are still gaps in the understanding of this tragic event.

Why, after repeated warnings and requests from both Chinese and American officials, did Alfred Bernheim not move his family to a safer area? What can we learn about Consul Troy Perkins, who seemed to be so involved with the Bernheim family and took such an interest in the children’s welfare? What was it like for the surviving children who had to make the transition from rural China back to the United States? Finally, what more can we learn about Deaconess Julia Clark, whose courage and determination supported the Bernheim children at such a critical time in their lives?

This story, which once made U.S. headlines, quickly faded from memory but lives on in the files of the Foreign Service.

Cynthia Peterman is an education volunteer at the National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Note on Sources

The Volunteer Office at the National in College Park was assigned a project in the Records of the Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, Record Group (RG) 84. Volunteers were given the task of taking old binders stuffed full of documents, carefully unbinding them, and creating newly labeled archival folders to allow researchers to better use these records of Foreign Service posts. The Bernheim story is in File Yunnanfu (Kunming), 1940, 330 (a, a-b), Entry 53, RG 84. The file contains correspondence, reports, and newspaper clippings, and an interview with the District Magistrate of Chanyi dated November 11, 1940, which described the interrogation of the bandits.

Becky Croasmun, daughter of Mark Bernheim, published her grandparents’ letters in Legacy of Faith (Bloomington, Indiana: iUniverse Inc., 2011). John Stewart Service, vice consul in Kunming from 1933 to 1941, wrote his description of Yunnan province in American Diplomats: The Foreign Service at Work, ed. William D. Morgan and Charles Stuart Kennedy. (New York: iUniverse, Inc., 2004). Newspaper coverage included “Americans Slain in China: Robbers Kill 2 and Wound 2 of Spokane Missionary Family,” New York Times, November 8, 1940, and “Bandit Gang Pursued: Chinese Offer Rewards for the Killers of 3 Americans,” New York Times, November 12, 1940. The local Spokane papers also carried stories of the children’s experience and return to Spokane. Photographs of the children’s arrival were donated to the Tacoma Public Library.

PDF files require the free Adobe Reader.

More information on Adobe Acrobat PDF files is available on our Accessibility page.