Broken Blossoms

A Struggle from Servitude to Freedom

Spring 2016, Vol. 48, No. 1

By Edward Wong

© 2016 by Edward Wong

A broker in Hong Kong had promised that she would have a job and perhaps marriage to a Chinese merchant in America. Gwai Ying was very tempted by the offer because the worldwide economic depression meant that there were few jobs for her in China. Marrying a wealthy Chinese merchant in the United States was an attractive proposition.

Gwai Ying assumed the false name of Lee Lon Ying to circumvent the restrictive U.S. immigration laws. After she passed interrogations by immigration officials and was admitted to the United States, her life in the United States took a dark and sinister turn. The man who paid for her passage from China took away her legal papers. He then sold her into the thriving prostitution business in San Francisco, where she remained essentially a slave until she found a way to escape.

This story tells how Jeung Gwai Ying and others testified against their slave owners and won convictions in San Francisco federal court in what was known as the “Broken Blossoms” trials.

The Roots of Prostitution In San Francisco’s Chinatown

Prostitution was firmly established in San Francisco’s Chinatown long before Jeung Gwai Ying arrived there.

Chinese immigration to the United States began in the 1850s, shortly after the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Creek near Coloma, California. By 1860, there were 2,719 Chinese in San Francisco; most of them were male. Because of Chinese cultural mores against women traveling abroad, limited economic resources to pay for their passage, and the harsh living conditions in the American West, it was safer for a man to support his family in China from across the ocean.

Later, Chinese men who wanted to bring their families to join them were prevented from doing so by anti-Chinese immigration laws like the 1875 Page Act, which prohibited the immigration of Asian women brought in for prostitution. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act restricted the immigration of all Chinese workers (merchants, ministers, students, and diplomats were exempted) and allowed entry only for Chinese women who were daughters or wives of Chinese merchants or U.S.-born Chinese.

Because of these restrictions, the Chinese population in the United States was more than 90 percent male from 1860 to 1910.

Chinese tongs, or secret societies, began to import Chinese women to fill the demand for prostitutes by Chinese laborers as well as by whites. In early 1854, one company imported 600 female prostitutes to San Francisco. Between 1852 and 1873, the Hip Yee Tong trafficked 6,000 women, bringing in $200,000 in profit. According to the 1870 census, 1,565 Chinese prostitutes worked in San Francisco, and they constituted 61 percent of the entire Chinese female population.

By 1880 the population of Chinese women forced into prostitution in San Francisco had declined to 305. This was due in part to the influence of social reformers, the enforcement of anti-prostitution laws, and the exportation of Chinese prostitutes to other cities in California and throughout the western states.

During this same period, the number of married Chinese women also rose as men who intended to stay in America began sending for wives. Many former prostitutes left the trade and married Chinese laborers and merchants in America.

To circumvent the restrictive immigration law, the prostitution ring leaders arranged false marriages between Chinese women and American-born Chinese and Chinese merchants. Other women obtained entry as the alleged daughters of American-born Chinese and Chinese merchants. Once these women were settled in the United States, they were forced to become prostitutes and treated as slaves by their owners.

Even after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake leveled Chinatown, destroying all the slave quarters in one mighty conflagration, the prostitution racket resumed. Prostitutes were arrested and deported while slave owners often escaped prosecution. In the June 1921 issue of Women’s Work, a Christian journal, Mabel M. Roys, a supporter of the Presbyterian Mission Home, remarked on the conviction of a Chinese slave owner who received a one-year sentence: “in the course of the 47 years of this rescue work, the convictions have been negligible.”

A 1935 trial, however, proved to be a significant victory in the crusade against Chinese sexual slavery. It became known as the Broken Blossoms case.

Jeung Gwai Ying’s Enslavement and Escape

It was a chilly winter evening on December 14, 1933, when Jeung Gwai Ying dashed to the Presbyterian Mission Home, located at 920 Sacramento Street, just a few blocks from the apartment where she had been held captive. Coerced into prostitution, Jeung hated her masters and was determined to break free. The Mission Home was renown in Chinatown as a haven for enslaved men and women. Donaldina Cameron, the director of the Mission Home, and her Chinese associates rescued 3,000 women and girls from 1899 to 1934.

In her statement to Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) Inspector August Kuckein on March 7, 1934, Gwai Ying told about her enslavement and her escape.

Q: How did you happen to come to the Mission Home?

A: . . . I told one of my customers that I couldn’t stand that kind of life, and he told me there was a Home I could go to where they could not reach me.

I waited my chance, and when I was sent out to have my hair done at 4:30 pm at a place about two houses from my apartment—I had been told that I was to be sent to the country at 5 o’clock [note: most likely to the Sacramento River Delta towns where many brothels serviced the farm laborers]—I went to the beauty parlor and told the girl to curl the ends of my hair only; then I left the beauty parlor and asked a child on the street where the Mission was. I was taken to a Mission on Washington Street and from there I was brought to Miss Cameron’s Home. That was on December 14 last year, or about 17 or 19 days after the final payment was made to Wong See Duck’s wife for me.

Jeung Gwai Ying’s family was very poor. They lived in Heungshan in Guangdong Province, where her father, Jeung Fat, was a schoolteacher. When her father died (three years before she went to the United States), her mother, Lee Shee, moved Gwai Ying and her nine-year-old sister and seven-year old brother to Hong Kong.

One day a family friend brought an old woman to visit Gwai Ying. The woman worked for Wong See Duck, a wealthy San Francisco merchant who was also a tong member involved in the prostitution racket. Wong See Duck periodically came to China to recruit women to come to America, promising them jobs or marriage to Chinese merchants in America.

Gwai Ying described what ensued:

A lady who speaks the See Yup dialect came to see my mother. She told my mother that she wanted me to come to the United States to work, and that if I would like to become a prostitute I could be wealthy within a year or so. . . . She came to see me ten days before I left Hong Kong for Seattle. There was no work in China, so I thought I would take a chance and come to get a position here. They told me that I didn’t have to become a prostitute if I didn’t want to, that I could get a job. . . . My mother didn’t want me to come, but our family is very poor, and I thought if I could get work in America it would help my family.

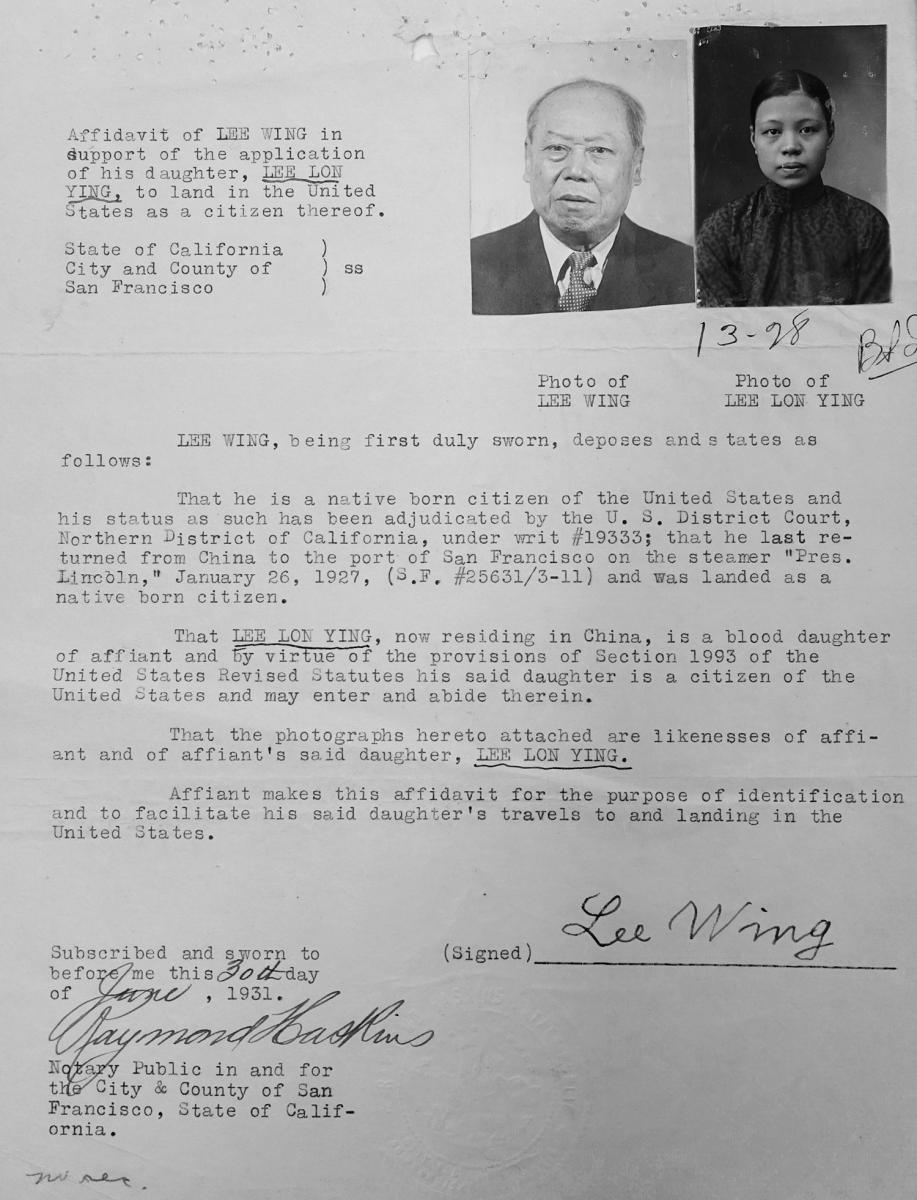

The old lady gave Gwai Ying’s mother $400 in Hong Kong dollars, which was approximately $115 U.S. A few days later, Gwai Ying went to the Ah Jow Hotel near the waterfront to study coaching papers, as she was to immigrate as Lee Lon Ying, the daughter of Lee Wing, a native-born Chinese man who lived in Seattle. Wong See Duck purchased her steamship ticket, and she prepared to leave China. She studied for three hours a day for three days to learn the names of her false brothers and sisters and the details of life in Wing Soon Village in the Sun Ning District of Guangdong, a place she had never visited.

Gwai Ying boarded the SS President Cleveland accompanied by Wong Quong Hing, a friend of Wong See Duck. Gwai Ying arrived in Seattle on July 21, 1933. Her alleged father, Lee Wing, and her alleged sister, Lee Gim Gook, who had arrived in February 1933 with Wong See Duck, were questioned by immigration officials separately from Gwai Ying. Their testimonies about their family history matched with Gwai Ying’s account, and she was granted a certificate of identity, which affirmed her legal status as an immigrant. After staying a few days in Seattle, Gwai Ying, Lee Gim Gook (whose true name was Leung Louie Gin), and Wong Quong Hing took the train to Oakland, California, where they were met by Wong See Duck. He promptly confiscated Gwai Ying’s certificate of identity.

Gwai Ying was taken to an apartment on the third floor of 900 Powell Street in San Francisco. Lee Gim Gook returned to the home of Wong See Duck and his wife, Kung Shee, where she did the family’s washing and cleaning while Wong See Duck sought a buyer for her.

Gwai Ying Describes Life As Prisoner in San Francisco

Gwai Ying lived in the Powell Street apartment for several months while Wong See Duck negotiated her sale. Wong See Duck’s wife, with her children in tow, visited her daily to bring Gwai Ying food and occasionally accompany her on walks. Gwai Ying was ordered to stay in the apartment. Not able to speak English and without a single friend in San Francisco, Gwai Ying was afraid to go out on her own.

In her statement to INS officials, she described how she was sold after several failed attempts:

Wong See Duck’s wife took me the third time to 826 Jackson Street, Apartment 205, San Francisco. At that apartment I saw a lady named Jew Gwai Ha and a lady named Yee Mar. After they looked me over, Wong See Duck’s wife took me back to the apartment where I was living. Wong See Duck and his wife told me I would have to enter a life of prostitution. I refused and Wong See Duck threatened me.

Q: In what manner did Wong See Duck threaten you?

A: He told me that if I refused to go it was either a case of “he dies or I die.” He had spent so much money in bringing me to this country, how could I pay him back the expenses? He told me that he would take me out of the apartment and place me in a very dark place.

A few days later, Gwai Ying returned to the apartment on Jackson Street with Kung Shee. A man named Sheung, who had negotiated the sale, was also present.

Gwai Ying described the final sale:

Eight or nine days after, a man came up to get my luggage and I was moved to 826 Jackson Street, apartment 205. . . . Jew Gwai Ha gave me two checks and some currency totaling $4,000, not including the $500, previously given me. [Note: Jew Gwai Ha had given $500 to Gwai Ying, who gave it to Wong See Duck, as a deposit on her sale.]

As soon as they [the money] were given to me I gave them to Wong See Duck’s wife. Jew Gwai Ha said to me “Now you see, the money has been transferred; now you belong to us” and that if I changed my mind Wong See Duck had to pay the money back to them. . . . Jew Gwai Ha told me that I would have to become a prostitute. That night an automobile came for me to take me to an apartment on Powell Street, where five or six men were present. A feast was then held. I stayed there that night with one man. Next morning, about 10 or 12 o’clock, Yee Mar came for me and took me back to 826 Jackson Street. . . . The man with whom I stayed that night was named Chan Cheung, a merchant of the Yee Cheung Co. of Seattle. He gave me $25. When I returned to the apartment at 826 Jackson Street, I gave $21 of that money to Jew Gwai Ha. I kept $4.

In her March 12 statement to INS officials, Gwai Ying stated: “I went to whatever hotel that my two owners sent me for the night. I practiced prostitution two times at the Tai Sing Hotel (706 Jackson St. at Grant Ave.) on two different nights; and over ten times at the Grand View Hotel (605 Pine St. at Grant Ave.). I was also taken to men’s rooms on Powell Street on three different occasions. . . . Some paid me $25 and some $30 for the night, but I had to turn in $21 as that was required by my owners for the night.”

Gwai Ying was not the only young woman at the Presbyterian Mission Home who had escaped from her slave owners. Although Quan Gow Sheung did not know Jeung Ying, they had something in common— both women had been owned by Jew Gwai Ha and Yee Mar. On November 10, 1934, 21-year-old Quan Gow Sheung gave a statement to INS officials.

Quan Gow Sheung’s Story Bolsters Gwai Ying’s Accusations

Quan Gow Sheung arrived in Seattle on November 7, 1927 on the SS President Jackson under the false name of Fong Dai Muey, the daughter of Fong Lem.

Quan Gow Sheung was met in Seattle by Goo Goo Yung, the wife of the man who tricked her into emigrating. She was taken to San Francisco and told that she would become a prostitute and the property of four women: Goo Goo Yung, Yee Mar, Jew Gwai Ha, and Yuen Yow. She lived under the watchful eye of Yee Mar and her husband, Yee Mee, on Commercial Street near Kearny Street for one year. Then she was sent to Sacramento to work for Yuen Yow.

Quan Gow Sheung was sold in 1929 to another slave owner, but she escaped with her friend Yoke Lan. She was 19 years old when she arrived at the Mission Home.

Despite Quan Gow Sheung and Gwai Ying’s sworn statements, Assistant U.S. Attorneys A. J. Zirpoli and Arthur Phelan proceeded cautiously and spent a year amassing more evidence. The INS files show that Wong See Duck, Kung Shee, Jew Gwai Ha, and Yee Mar had been suspected of criminal activities for many years.

Building a Case Against Wong See Duck, Others

INS files reveal that Wong See Duck was a member of the Suey Sing Tong and had been arrested on January 9, 1934, along with 17 other men at a tong meeting in Oakland’s Chinatown. Although no charges were levied, police were concerned about a possible tong war between the Suey Sing Tong and the Sen Suey Tong over an estate valued at $200,000 left by a deceased tong leader.

Wong See Duck was a prosperous merchant who owned a hardware store on Grant Avenue. As a merchant, his legal status allowed him to travel back and forth to China, and his wealth allowed him to finance the purchase of false identities and import women for sale into prostitution. Despite Wong See Duck’s activities, it is important to understand that not all members of tongs or community associations are criminals.

Wong See Duck came to the United States in 1908 when he was 19 years old under the false name of Leong Chong Po, a son of a merchant. He worked for several Chinatown companies, returned to China in October 1913, and got married there in December 1914. In 1923 he returned to China and brought his wife, Kung Shee, and their son and daughter to the United States.

Yee Mar arrived in San Francisco on September 25, 1909. She was 23 years old and entered as Louie Shee, the wife of a native-born Chinese man, Low Git, who worked at the Denver Bar on Fillmore Street. The couple moved to Watsonville, California, where Low Git worked as a cook in a Chinese restaurant. It was not a happy marriage. When Low Git applied to visit China in December 1914, he told INS officials that his wife had run away to San Francisco and become a prostitute.

When Yee Mar applied to visit China in October 1930, INS officials noted that Low Git had accused her of being a prostitute. Immigration Inspector H. F. Duff interviewed Sgt. John J. Manion, head of the San Francisco Police Department’s Chinatown Squad, who recognized the picture of Yee Mar and identified her as the wife of Yee Mee, a member of the Hop Sing Tong and Bing Kong Tong. He had operated the Siberia Gambling Club, an establishment that was known to have prostitutes on the premises. He had been arrested several times on gambling charges, and police shut down the club in 1916.

Yee Mar and Yee Mee were investigated again in May 1932. Tien Fuh Wu, a Chinese Associate at the Presbyterian Mission Home, heard that Yee Mar was planning to land a young slave girl who was accompanied by a 60-year-old merchant at the Angel Island Immigration Station, but immigration officials never found the girl.

The file on Jew Gwai Ha, who was admitted to the United States on October 1, 1923, under the name Fong Shee, does not contain much background information. She was granted admission as the wife of Hom Ngee, a native-born Chinese man who worked on a flower farm in Belmont, California. At some point, she left him and moved to San Francisco, where she gave birth to a daughter, Ruby Tom, in December 1926.

It is not clear when she became a slave owner. On March 19, 1934, San Francisco Police Inspector Manion went to Jew Gwai Ha’s apartment accompanied by representatives of the Presbyterian Mission Home and Quan Gow Sheung, who sought to reclaim her personal possessions. Police also confiscated photos of Jew Gwai Ha in the company of other slave owners.

In December 1934, the San Francico Police Department issued arrest warrants for Wong See Duck, Kung Shee, Fong Shee aka Jew Gwai Ha, and Louie Shee aka Yee Mar. They were rounded up in January and February 1935 and held briefly on charges of “illegal importation for immoral purposes and receiving and benefiting from prostitution.” After pleading not guilty at arraignment hearings in early February, the women were released on $2,000 bail each; Wong See Duck was released on $2,500 bail.

Broken Blossoms Trial Begins in Federal Court

On March 5, 1935, the trial began in federal court at the San Francisco Post Office Building in the chambers of Judge Albert Morris Sames. Unfortunately, records from the trial no longer exist. (Federal trial transcripts are scheduled for destruction 10 years after the trial.) However, the INS pretrial interviews with the accused give us a reasonable idea of the facts that the prosecution would have presented in court, particularly the contradictory statements made by the accused.

The INS questioned Wong See Duck and his wife, Kung Shee, on December 17, 1934. When confronted with Gwai Ying’s statements regarding her sale into slavery, Wong See Duck acknowledged that he had met her but said he did not know her well. He denied any guilt in the matter.

Kung Shee was questioned on the same day. She started with a straightforward denial of knowing Gwai Ying or having provided her food. When pressed by INS officials, Kung Shee did admit to receiving the $500 deposit on Gwai Ying’s sale.

Questioned by INS Inspector Kuckein on January 28, 1935, Jew Gwai Ha acknowledged being introduced to Gwai Ying by Yee Mar, her neighbor at the apartment building on 826 Jackson Street.

On the critical issue of the money exchanged as Gwai Ying was sold into slavery, Jew Gwai Ha verified that all the parties were together at the apartment. This is a crucial point because Yee Mar denied to INS officials even knowing Jew Gwai Ha let alone being a party to a sale.

Yee Mar was arrested at her apartment on February 13, 1935, and questioned that day. She shared the apartment with Yee Ah Lee aka Yee Sheung, who was cited by Gwai Ying as one of the brokers of her sale from Wong See Duck. Yee Mar’s main line of defense was that she was in Los Angeles for most of 1933 and could not have been involved with any sale.

Prosecutors had ample ammunition to expose the slave owners, but the trial did not prove to be an easy one.

A Difficult Trial For Gwai Ying

A brief article in a San Francisco newspaper described Gwai Ying’s testimony: “The star witness was Jung Gwai Ying, purported slave girl, who, it was charged, was smuggled into this country from Hong Kong and sold for $4,500.

She testified she had been sold by her mother, taken to Seattle as the daughter of an American-born Chinese, and turned over to Wong Duck and his wife to be marketed to the highest bidder.”

Defense attorneys subjected Gwai Ying to intense cross-examination. The attorneys seized upon one misstatement about being sold in Hong Kong to Wong See Duck to say that all Gwai Ying’s testimony had been perjured. Mildred Crowl Martin, author of Chinatown’s Angry Angel: The Story of Donaldina Cameron, writes, “Kwai Ying hesitated, tried to answer, floundered under the cruel rain of words, and fell silent, covering her face with trembling hands.”

In the end, 10 jury members cast a guilty vote, but two jurors were not convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that the accused were guilty. The judge declared a hung jury; the accused were released. However, the slave owners were not completely exonerated.

Gwai Ying had spoken to INS officials about another young woman who was at Wong See Duck’s Powell Street apartment and who had been sold into slavery. Her name was Wong So, but she could not be located during the yearlong investigation before the first trial. Three days after the trial ended, she was arrested in Salinas, California, at the Republic Hotel and brought to the Presbyterian Mission Home in San Francisco. In a series of INS interrogations from March 16 to 20, 1935, Wong So revealed how she was sold into prostitution.

Wong So was an only child. Born in Ching Jow village in the Heungshan district of Guangdong Province China, she moved to Macao with her father, who owned a small grocery store. After he died, when she was 13 years old, she went to live with a distant cousin in Macao and worked at a firecracker factory.

Wong So Paves the Way For Second Federal Trial

One day Wong Quong Hing, a friend of her cousin’s, visited the family and suggested that Wong So come to the United States and get married. This man was the same man who accompanied Gwai Ying to America in July 1933. Acting on behalf of Wong See Duck, Wong Quong Hing arranged for Wong So’s sale.

In order for Wong So to immigrate to America, she would need to assume the identity of Lee Choy Ying, daughter of Lee Wing (the same false “father” assigned to Gwai Ying). Wong So was given a 100-page coaching book, and Wong Quong Hing tutored her for a month at the Ah Jow Hotel.

She boarded a steamship by herself and arrived in Seattle on May 28, 1933. Wong See Duck, along with Kung Shee and Lee Gim Gook, met her. Lee Gim Gook testified that Wong So was her sister, as did Lee Wing, her false father. After staying in a Seattle hotel for one week, Wong So, Wong See Duck, Kung Shee, and Lee Gim Gook traveled by train to San Francisco. Wong So moved into Wong See Duck’s house and shared a room with Lee Gim Gook. There, she waited to be sold in prostitution.

A few weeks after Wong So’s arrival in San Francisco, negotiations began with Ho Sek Mo (the wife of Ho Siu Hon, President of Bing Kung Tong). Ho Sek Mo gave $5,200 in currency to Wong So, who then gave it to Kung Shee, who gave it to Wong See Duck. For a total price of $5,400, Wong So was sold into prostitution on July 1, 1933.

Wong So’s testimony also bolstered Gwai Ying’s story. When shown photographs of Jew Gwai Ha and Yee Mar, Wong So identified them as “gwai po,” owners of prostitutes. Wong So stated that the slave owners socialized with one another and identified them in a group photograph taken from Jew Gwai Ha’s apartment by INS officials.

Armed with Wong So’s testimony, U.S. prosecutors scheduled a new trial on April 31, 1935.

Federal Lawyers Prepare for Broken Blossoms Trial

Assistant U.S. Attorneys Zirpoli and Phelan laid the foundation for the second trial of Wong See Duck, Kung Shee, Jew Gwai Ha, and Yee Mar with a press conference on April 18. Their accusation that a criminal ring had smuggled more than 50 women into the United States each year was splashed across the front page of the San Francisco Examiner in a banner headline: “S.F. Slave Girl Names High Ups—$5,000 Paid for Victims of Vice Syndicate.”

On May 2, the San Francisco Chronicle reported on Wong So’s testimony that she had been bought in Hong Kong for about $200 American and resold in the United States for $5,000. The reporter described Wong So as confident and determined as she spoke from the witness stand:

"Wong So took her chair, brushing her short hair behind one ear. She made her statements with vigor, and she stood up under fire. Moreover, she bore herself with a dignity that was unshakeable."

The jury considered the evidence on May 3 and, after meeting for one hour, voted unanimously to convict Wong See Duck, Kung Shee, Jew Gwai Ha, and Yee Mar.

The three women were sent to the Federal Industrial Institution for Women in Alderson, West Virginia, for one year. Wong See Duck was sentenced to prison for two years at McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary in Washington, but he served only one year.

On May 3, 1936, Wong See Duck was released from prison on bond but was held at the Angel Island Immigration Station prior to his deportation. On October 15, 1936, Wong See Duck and Kung Shee, accompanied by their American-born children, 12-year-old William, 11-year-old Diana, and 8-year-old Simon, boarded the President Lincoln and were deported to China.

Yee Mar and Jew Gwai Ha were both released from prison in February 1936. Yee Mar returned to San Francisco and appealed her deportation. Her appeal was denied and she was deported to China on April 13, 1938, on the SS President Coolidge.

After posting a $3,000 bond, Jew Gwai Ha returned to San Francisco to appeal her deportation order. Her attorney appealed for a delay so that her American-born daughter, Ruby Tom, age 9, could finish out her school term. It is not clear whether Ruby accompanied her mother on April 13, 1938, when Jew Gwai Ha was deported to China on the SS President Coolidge.

Three Stay at Mission Home While Facing Deportation

Wong So, Quan Gow Sheung, and Jeung Gwai Ying continued to live at the Presbyterian Mission Home after the trial and deportation hearings concluded against the slave owners. All three were subject to deportation because they had entered the United States under false identities, but only Wong So was forced to leave. She sailed on September 26, 1936, aboard the President Coolidge and later entered a Mission School in Shanghai, China.

Quan Gow Sheung converted to Christianity while living at the Mission Home. Consistent with the practice of the home, the staff found a suitable Christian mate for her, and in 1937 she married Stephen Yee.

Gwai Ying’s story was more complicated. During Yee Mar’s deportation hearing on November 29, 1935, the INS inspector questioned Gwai Ying about her son, David, who was born on May 18, 1934. She refused to name the father, although it was widely speculated to be Wong Quong Hing, the man who accompanied her to the United States and who stayed with her in a San Francisco apartment.

Wong Quong Hing Returns, Has Reunion with Gwai Ying

According to Wong Quong Hing, Gwai Ying stopped first at the Jung Hing Hotel on December 14, 1933, to tell him that she planned to escape to the Mission Home that night. A few days later, articles appeared in the Chinese press about Gwai Ying’s escape. Wong Quong Hing knew that he would be arrested for his role in the false immigration of Lee Wing’s alleged daughters. He boarded a ship in Seattle bound for China on December 23, 1933.

On January 11, 1941, Wong Quong Hing returned to the United States and contacted Gwai Ying at the Mission Home in San Francisco. After his first wife died in China in February 1941, Cameron arranged for Wong Quong Hing and Gwai Ying to be married in Santa Cruz on May 22, 1941.

He turned himself in to the INS and was questioned in October 1941 to determine his right to stay in the country. Wong Quong Hing said that he did not know that Wong See Duck intended to bring women into the United States for prostitution. Because Wong See Duck had paid for the hospitalization and care of Wong Quong Hing’s father, who was a business partner, Wong Quong Hing felt indebted and heeded his instructions.

Wong Quong Hing pled guilty to the charges of fraudulent immigration for the purpose of prostitution and was placed on five years’ probation on November 22, 1941. Working in his favor was the fact that he derived no financial gain for any of his activities on behalf of Wong See Duck.

Gwai Ying adopted the name of Lois Qui Wong. She and her husband, now known as Henry Quong Wong, lived in San Francisco with their son. On February 7, 1942, Lois gave birth to Donna Li Wong. Two years later, Lois and Henry’s son, Franklin You Wong, was born on January 15, 1944. Lois spent the rest of her life as a homemaker.

Both Lois and Henry lived out their lives in San Francisco; Lois passed away on May 14, 1999, and Henry died on May 6, 2008. The convictions of slave owners in the Broken Blossoms trial were hailed as a victory in the fight against powerful criminals in San Francisco’s Chinatown.

Chinatown was also changing in the late 1930s. The Great Depression had slowed immigration from China, and after the Sino-Japanese war broke out in 1937, travel from China to America slowed considerably.

The Broken Blossoms trials revealed the persistent exploitation of Chinese women that runs through Chinese American history. Because U.S. laws forbade the importation of wives of Chinese laborers, criminal syndicates were quick to exploit the situation. The market that was set up to provide sexual services for Chinese men, both laborers and merchants, was founded on coercion. This ugly side of Chinese American history is not often acknowledged.

Epilogue

Sophisticated criminal gangs continue to import women from Asia to work as prostitutes in the United States. In October 2014, a San Francisco federal grand jury indicted 10 defendants for recruiting women from Singapore, China, Hong Kong, Thailand, Taiwan, Vietnam and the Philippines to work in 40 brothels in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Wire transfer records reveal that $288,518 was sent to recruiters in Asia to entice women to come to the U.S. where they were kept in apartments that served as brothels. The cases are currently going to trial.

Although the Broken Blossoms case is largely unknown to the public, Jeung Gwai Ying, Quan Gow Sheung, and Wong So should be remembered and hailed for their courage and tenacity. They survived daunting circumstances with great determination and dignity. Equally important in the successful prosecution of the Broken Blossoms case was the role of the Presbyterian Mission Home, now known as Cameron House.

For decades, the staff led by Donaldina Cameron had protected slave girls and other exploited children from the criminal gangs. They not only provided a safe haven, but they also persuaded police, the courts, and immigration officials to pursue the gangsters who ran the prostitution rackets. To the fullest extent possible, the Mission Home staff counseled the women to seek justice in the courts.

The Broken Blossoms case was a significant victory, but the war against exploitation of women continues today.

Edward Wong is enjoying his retirement years doing research and writing on Chinese American history. He is the former executive director of the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation and the former executive director of the Center for Asian American Media. He graduated from UCLA with a BA and MFA in Film Production and was a founder of Visual Communications, the nation’s first Asian American nonprofit media production company.

Note on Sources

I wish to thank Charles L. Miller and Bill Greene at the National Archives at San Francisco and Brita Merkel at the National Archives at Seattle for their help in locating the immigration records of all parties in the Broken Blossoms case. The majority of the information can be found in U.S. District Court, Northern District of California Criminal cases files: #25293, 25294, 25295 U.S. v. Wong See Duck Loc B/12/2/5/5.

Doreen Der-Mcleod, former director of Cameron House, provided invaluable assistance in locating files and photos of Wong So, Quan Sheung Gow, and Leong Lin Gin.

Tami Suzuki at the San Francisco History Center at the San Francisco Public Library guided me through their historical photographic collection. Tim Wilson at the San Francisco Public Library also helped me find several of the locations mentioned in the article.

Leah Chen Price at Asian Pacific Islander Legal Outreach in San Francisco provided insights on contemporary human trafficking and its impact on Asian Pacific communities.

I am deeply grateful to Judy Yung, whose editorial advice was invaluable.

This article is a condensed version of my article “The 1935 Broken Blossoms Case: Four Chinese Women and Their Struggle for Justice.”