Walking and Talking with Harry

Winter 2015, Vol. 47, No. 4

By Leonard Rubin

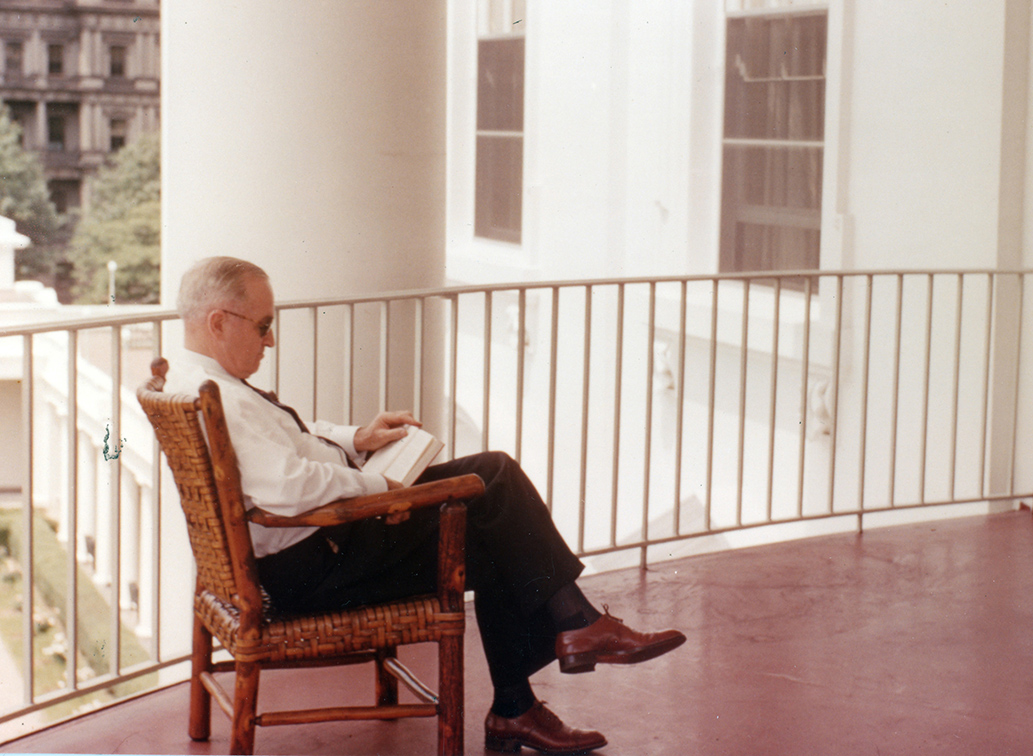

Earlier this year, the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum in Independence, Missouri, received for its holdings a manuscript from Caryl Lee Fisher of New York City. It was written by her late father, Leonard G. Rubin, who took long walks with former President Truman in the 1950s and 1960s, when the 33rd President and his wife visited their daughter, Margaret Daniel, and her family in New York City.

Although the library knew of the walks in New York, it never had any account of them. Samuel Rushay, supervisory archivist at the Truman Library, said there are records in the library’s holdings that clearly indicate that Truman and Rubin walked together regularly in New York City during Truman’s post-presidency.

Rubin first met Truman shortly after Truman left office and returned to Missouri. In those days, former Presidents received no Secret Service protection and only a modest amount for office expenses. Truman himself was not wealthy compared to other ex-Presidents and could not afford the fancy surroundings his successors enjoy.

Most of the opinions Truman expressed in the walks have since been incorporated into biographies and Truman’s own memoirs. A few others are excerpted here.

Leonard Rubin found Harry S. Truman to be cordial, down-to-earth, and an interesting walking companion.

My remarkable experiences with President Harry S. Truman began on a spring day in 1953 when I was in Kansas City, Missouri, on a business trip. I had a 9 a.m. appointment with some top executives that concluded quickly by 9:45. My flight back to New York City was not scheduled to depart until 2:30 that afternoon. Therefore, I had several hours to kill between 10 a.m. and early afternoon in Kansas City.

I wasn’t really sure that sightseeing in Kansas City would be very exciting; however, I hailed a taxi and told the driver to take me to the then-famous Muehlebach Hotel. Then I remembered reading in a news magazine that since Eisenhower had been elected, former President Truman had moved back to Independence, Missouri, and was driven into his Kansas City office each weekday morning.

I asked the driver if he knew where Mr. Truman had his office. Luckily, the driver knew and took me to the Federal Reserve Building. I had always admired President Truman and figured that I had nothing to lose by stopping by, seeing if he was in, leaving a business card or maybe a note and possibly be lucky enough to introduce myself and shake hands. If he wasn’t there, I could always sightsee or go to a movie.

I entered the Federal Reserve building and looked at the directory board on the main floor. There was a simple entry listing “Truman, Harry S. 11th floor.” In this old building, all of the offices had frosted glass door panels with the name of the company or person in black letters on the glass panel. I opened the door marked “Harry S. Truman” and entered a very ordinary office with a small reception area and a receptionist seated at a desk facing the entrance door.

I approached her with my business card in hand and said, “Is Mr. Truman in? I don’t have an appointment.” The receptionist took my card and went down a hallway that had three offices on each side and a larger double office door at the end of the hallway.

I remember thinking how very unpretentious everything was. It could have been the office of any small business establishment or law firm. The fact that it was located in the Federal Reserve Building meant that it would not cost the government any rent or use any of the allowance given to ex-Presidents for office space. [In those days, ex-Presidents received no pension, and Truman received only a $112.56 a month military pension until Congress passed the Former Presidents Act of 1958, which provided a presidential pension. He also had no Secret Service protection until the assassination of President Kennedy.]

Truman Begins Visit with Insights into Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address

In keeping with his reputation, Mr. Truman was frugal about spending government funds, even when he was no longer in office. As a senator, during the war, he had saved the government hundreds of millions of dollars by heading a committee that reviewed defense contracts.

Looking to my left, I watched as the receptionist knocked on the door of the double office at the end of the hallway, entered and stepped out of sight. A moment later, Mr. Truman stepped out of his office and, seeing me looking in that direction, motioned for me to come in.

I couldn’t believe my luck that, not only was President Truman there at that particular time, but he was also willing to see me. I thought that he would probably give me a few minutes and send me on my way. Since I had asked to see him, I needed to think of an opening remark that would explain my visit.

It has been observed by historians that often after a new President is elected, the media and the public find fault with the outgoing President and make comments about all of the things the outgoing President should have done or not done while in office. Being an avid student of American history, I remembered reading that for years after the end of their terms, Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, and others were severely criticized for all of their “mistakes.”

Therefore, my opening remark was “Thank you for seeing me, Mr. Truman. I wanted to tell you that I am certain that historians will treat you much better than your contemporaries.”

To my surprise, Truman’s instant reply was “Did you know that many comments and reports about Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address were extremely uncomplimentary and insulting?”

I replied that although I owned and had read all six volumes of Carl Sandburg’s great biography of Abraham Lincoln, I did not recall any particular comments about the famous speech. Mr. Truman said, “When you get home, look it up and you will be surprised about what you read.” Later, when I looked at the passages that Truman had referred to, I appreciated what a brilliant response he had made to my opening remark.

Next, we began talking about U.S. history, Presidents, and what made them great. An hour went by, which, at the time, seemed like a few minutes. Another hour went by. I was fascinated by Mr. Truman’s knowledge of American history. I knew that he had not graduated from college.

Impromptu Visit Ends with Invitation to Join Truman in New York Walks

However, this two-hour conversation changed my entire image of former President Truman, whom, until that point, I had believed to be an intelligent, self-taught individual. Mr. Truman stunned me with his knowledge of American history, past Presidents, and his understanding of the details of congressional legislation.

For example, he was an expert on every detail concerning the Missouri Compromise (States admitted to the union after 1820 would be admitted in pairs, one slave and one free to maintain the balance). He knew the exact statutes in the law books concerning this matter, including the names of the legislators involved. He also had a complete understanding of the impact of the Missouri Compromise on the states admitted to the union after 1820, especially during the Civil War years.

Truman had an excellent memory and often remembered small details about topics that interested him in the areas of economics, sociology, and education. After our chat, I believed that he could have easily been the chairman of the American History Department at Harvard University! At that point, I concluded that the opening remark that I had agonized over had been the perfect one to touch off our discussion.

Finally, Mr. Truman glanced at his watch and said, “We will have to end this interesting conversation. The ‘boss’ will be expecting me.”

I knew that he was referring to his wife, Bess, with whom he had lunch every day at their home in Independence. As we left his office together, he asked me, “Can I give you a lift?” I replied, “No thank you. I like to walk, and my hotel is just a short distance away.”

We walked out of the office, followed by the man assigned to guard the ex-President. Truman commented, “You like to walk? I come to New York from time to time to visit my daughter. She . . . lives on the east side of Manhattan. I’ll have my secretary drop you a line and tell you the next time I am in town. I stay at the Carlyle Hotel, and you can come over and we’ll walk and talk again.”

I was flattered by Truman’s interest in continuing our discussions. I told him that I owned the biography of him written by Hillman. “If I had known that I was going to see you, I would have brought it along for you to autograph,” I said. Truman replied, “Send it to me. I’ll sign it and send it back to you.”

We reached the street where his car and driver were waiting. He shook my hand and said, “I’ll see you in New York,” got in his car with the guard, who sat with the driver and drove back to Independence.

Several Months Pass; A Postcard Arrive

I returned to New York, doubting that a man as busy as a former President of the United States would really take the time to contact me again about walking with him. Nevertheless, the possibility of being Harry S. Truman’s walking companion and discussing history and public affairs again was extremely appealing. Would it really happen? Would I get the invitation he had promised in Kansas City?

The answer to my questions came about two months after our meeting in Kansas City.

A simple postcard from Mr. Truman’s secretary said, “Mr. Truman will be at the Carlyle Hotel on such and such dates. Please be down in the lobby at 7:00 a.m. Mr. Truman’s walks usually last 30–40 minutes.” On the date mentioned, I made certain that I was in the Carlyle lobby at least a few minutes before 7 since I was certainly not going to keep the former President waiting! Mr. Truman was in the habit of changing his walking routes every day, sometimes walking uptown or downtown on Madison Avenue, into Central Park or farther east to Park Avenue, Lexington Avenue, or Third or Second Avenues.

I was still having difficulty believing that an ordinary person like myself had the opportunity to talk with a former U.S. President and directly ask him the kinds of questions that a history buff like myself would ask. I thought of our first conversation in Kansas City and the wide range of topics we had covered, particularly about politics and the office of the President and its former occupants. I thought that it would be interesting, if these walks did indeed continue over time, to follow one subject at a time with me asking questions and Mr. Truman doing most of the talking either off the cuff or answering and commenting on my questions.

Mr. Truman did not like small talk but loved to talk about current political issues along with past historical events. What Congress was or was not doing currently and what then-President Dwight Eisenhower was saying and the newspaper positions on the events of the day were topics of interest to him. I realized that Truman got early delivery of the New York Times and had already glanced through the paper before our walk began. I made a mental note that on any future walks, I would be sure to look through the paper as well, paying particular attention to what was happening in Washington, D.C., and noting any other world events that related to the United States.

Truman Boasts That He’s Read Biographies of all U.S. Presidents

Over time, we developed a routine of my asking him to comment on a broad question or some relevant political or current issue. Mr. Truman would answer and I would comment on his answers or ask follow up questions. Occasionally when I disagreed with him about his analysis, I spoke up about it. He liked this as long as my argument had a sound basis.

Philosophically, I was in agreement with him most of the time, having been a loyal Democrat for my entire voting career. In some cases, I was perhaps a bit more liberal than the former President, but, in general, we were both “middle of the road” individuals. Truman was very fair minded and tolerant of differing opinions.

Early in our relationship, President Truman made this statement to me: “Mr. Rubin, I am perhaps the only President who has read the biographies of every one of my predecessors. In truth, where I thought that a particular occupant of this office was not important for one reason or another, I read a short biography of that individual. For example, William Henry Harrison only served one month in office and John Tyler became the first Vice President to succeed to the presidency. In 1848, Zachary Taylor, a Whig won the election. After a year in office, Taylor died and was succeeded by his Vice President, Millard Fillmore. . . . However, one of the greatest biographies of a US President is Carl Sandburg’s six-volume biography of Abraham Lincoln which I read from cover to cover. So you might say, I am a self-taught ‘expert’ on the presidency of the United States.”

He served first in local political offices and was later elected senator from his home state of Missouri. As a senator, he fought to save money for his country and at the same time help make decisions that would help win the war. He was selected to be Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Vice President for his fourth term. Harry S. Truman personifies the American dream, showing how far an honest, smart, hard-working person can go in the great democracy of the United States.

As I had noted when I visited Mr. Truman in Kansas City, his lack of pretentiousness was striking. After a few walks, I couldn’t resist asking Mr. Truman what he ate for breakfast. Staying at one of New York’s quiet but elegant hotels, I might have expected him to say that he ordered Eggs Benedict or some other fancy item. However, true to form, his answer was, “Usually, I start with orange juice, then cereal—Corn Flakes on hot days and oatmeal the rest of the time. I’m not a coffee drinker and prefer milk. Sometimes I add a little buttered toast.”

After all of the years that have passed, I wasn’t certain about what, if anything, I would do about putting an account of these walks with President Truman on paper.

Finally, when I had more time and my years of “9-to-5” activity were over, at the urging of my daughter, I began to record my experiences with the former President in some detail. Luckily, I had the presence of mind to make some notes at the time of the walks themselves so that the chapters really do reflect an accurate “from the horse’s mouth” account rather than the misty memories of walks taken 40 or more years ago. However, all of my records are not completely accurate regarding dates because walks were canceled.

Occasionally there were walks where some personal matters such as his trips, vacations, grandsons’ birthdays, or daughter’s surgery were discussed and, out of respect, I omitted reconstructions of these conversations.

The walks and talks took place over a three-year period. Mr. Truman usually stayed for a week to 10 days on each of his visits to New York City. During each stay, we usually managed to have anywhere from two to five opportunities to walk together. At the end of each walk, he would either say “See you tomorrow,” “Skip tomorrow and I’ll see you the day after,” or “call me about scheduling our next walk.” This article represents the discussions had over approximately 15 to 19 different meetings in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

In writing about these walks with Mr. Truman, I have omitted my replies or comments unless they contributed materially to the subject matter. I have tried to accurately reconstruct Mr. Truman’s words and ideas in the first person and not my own since I believe these have value and interest to others.

Leonard George Rubin was a liaison executive for the Non-Governmental Organizations of the United Nations, former marketing executive, and faculty member of New York University’s School of Continuing Education and FIT. He died December 26, 2000, in New York City. He was 86.

PDF files require the free Adobe Reader.

More information on Adobe Acrobat PDF files is available on our Accessibility page.