Tea and Equality

The Hoover Administration and the DePriest Incident

Summer 2015, Vol. 47, No. 2

By Annette B. Dunlap

On Wednesday, June 5, 1929, a courier from the White House, who was sworn to the utmost secrecy, delivered a handwritten invitation to the home of Congressman and Mrs. Oscar DePriest, at 419 U Street, NW, inviting Mrs. DePriest to a tea the following week, on June 12, at 4 p.m.

We do not know if Jessie L. DePriest had advance notice to expect the messenger, but the invitation certainly must have given her a sense of satisfaction. She was the wife of the only African American member of Congress, and she was being formally invited to socialize with the new First Lady, Lou Henry Hoover.

Since moving into the White House on March 4, Lou Hoover had hosted four other teas for the wives of the members of the cabinet and the Congress. The initial tea, held on May 27, included the cabinet and Supreme Court wives, the wives of the congressional leaders, and Vice President Charles Curtis’s sister, Dolly Gann, who served as hostess for her widowered brother. Invitations for the subsequent teas were issued in alphabetical order. When Jessie DePriest was omitted from the May 29 tea, the one attended by the “D’s,” she likely drew the obvious conclusion—she had been excluded because of her race.

Jessie taught music before her marriage to DePriest on February 23, 1898. She had been born in Rockford, Illinois, where her Pennsylvania-born parents had moved shortly after the end of the Civil War. In the 1880 census, Jessie’s father, James Williams, is listed as white. Her mother, Emma Williams, is recorded as mulatto. Jessie and her two older sisters are also listed as mulatto.

Photographs of Jessie DePriest from the congressional years depict an elegant and stylishly dressed woman, who was later remembered as being gracious and attentive to the needs of others.

Oscar DePriest was the first African American elected to Congress since the departure of Representative George H. White, of North Carolina, from the House in 1901. Oscar was born in 1871 in Florence, Alabama, the son of former slaves. DePriest’s father, Alexander, was a teamster and a farmer, and his mother, Mary, was a laundress.

Following the end of Reconstruction and a resurgence of violence toward African Americans in the Deep South, the DePriest family migrated with thousands of other black families in 1878 to the Midwest. They settled in Salina, Kansas, where DePriest attended public school and studied bookkeeping at Salina Normal School.

Oscar DePriest Goes to Chicago for Work

In 1889, DePriest was part of the black migration to Chicago, which was then the fastest growing city in the United States. He found work in home construction and eventually opened his own business and managed a real estate firm.

Oscar settled in Chicago’s Second Ward, which was a predominantly African American community, and he became involved in local politics. The ambitious young businessman was the first African American to be elected to the Chicago City Council. DePriest’s success in Chicago politics was so rapid and remarkable that it was publicized nationwide in the black press.

African Americans from across the country followed his career with keen interest. DePriest was a counterweight to men such as Booker T. Washington, and his successor as president of Tuskeegee Institute, Robert R. Moton, who did not openly challenge segregation and discrimination.

DePriest was elected to Congress from Chicago’s South Side. The seat had long been held by Martin B. Madden, a powerful member of Congress and chair of the House Appropriations Committee. When Madden died unexpectedly in April 1928, DePriest was chosen by the local Republican committee to replace Madden on the ballot.

Nationally, racial issues had bubbled below the surface during the 1928 presidential campaign. Southerners recalled Hoover’s decision, as secretary of commerce, to eliminate a segregated, all-black unit of the Census Bureau and integrate the employees into the organization. Mississippi’s governor, Theodore G. Bilbo, charged that Hoover had danced with a black member of the Republican National Committee. The Hoover campaign quickly denied the accusation.

In fact, Hoover and his organization were doing everything they could to distance themselves from the perception that they favored equal rights. Hoover’s campaign promoted racially conservative views among the Southern Republican organizations and encouraged the appointment of whites to party positions that had previously been held by blacks.

The Republicans’ efforts sought to capitalize on Southern Democrats’ disaffection with the party standard bearer, Alfred E. Smith. The New York governor was a Catholic, pro-immigration, and favored the end of Prohibition. The Hoover strategy worked. “Hoovercrats”—Democrats who voted for Hoover—helped give him a majority in Virginia, North Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, Oklahoma, and Texas.

Southerners Try to Bar DePriest, But Speaker Outmaneuvers Them

When the new Congress convened on April 15, 1929, Southerners sought to prevent DePriest from being seated. The Speaker of the House customarily swore in the individual delegations by state, and segregationists threatened to block the swearing-in of the Illinois members. House Speaker Nicholas Longworth, at the urging of his wife, Alice Roosevelt Longworth, the outspoken daughter of President Theodore Roosevelt, made the decision to swear in the entire House as one body.

Mrs. Longworth had been influenced by her friend, Chicagoan Ruth Hanna McCormick, herself a newly elected member of Congress, and a friend of DePriest’s. In his explanation for the change of practice, Longworth observed that the delegations who were not being sworn in were often loud and unruly. The swearing in of all members at one time, he explained, would preserve the decorum of the ceremony.

Longworth’s move deftly derailed the threatened boycott, but it did not defuse the anger toward a black member of Congress. North Carolina Democrat George Pritchard refused to take his assigned office space next to DePriest’s. Several Southern members of Congress threatened to boycott their committee assignments if DePriest served with them. Socially, the DePriests were ignored by official Washington.

In the meantime, Southerners began to have second thoughts about Hoover. Newspapers grumbled that he had selected no Southerners for his cabinet. Republican Representative George H. Tinkham, from Massachusetts, sent a letter to Attorney General William D. Mitchell at about the time the House was sworn in, charging that he was not upholding the 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution, which guaranteed equal rights for blacks.

When Mitchell took no action on the letter, Tinkham and Kansas Republican Homer Hoch added amendments to the census bill to reduce the representation in Southern states because blacks were disenfranchised. The bill came up for a vote in early June. Smart parliamentary maneuvering by Speaker Longworth led to the defeat of the amendments, but Tinkham’s and Hoch’s stance further inflamed Southern members of Congress, almost all Democrats, against the Republicans and, by extension, against the President.

This political backdrop framed Lou Henry Hoover’s planning for the teas. On May 11, her social secretary, Mary Randolph, sent a note to President Hoover’s aide, Walter H. Newton:

In connection with the projected Congressional Teas, the question arises as to what can be done about the family of our new colored representative. Mrs. Hoover wishes me to ask for your suggestion, and to remind you that we must think not only of this occasion, but of what is to be done during the entire term of the Representative.

Will you please let me have an immediate reply.

Newton’s reply cannot be located in the archives of the Herbert Hoover Library, but a notation at the top of the invitation list for the first tea indicates, per Newton’s recommendation, that the congressional wives were to be invited in alphabetical order.

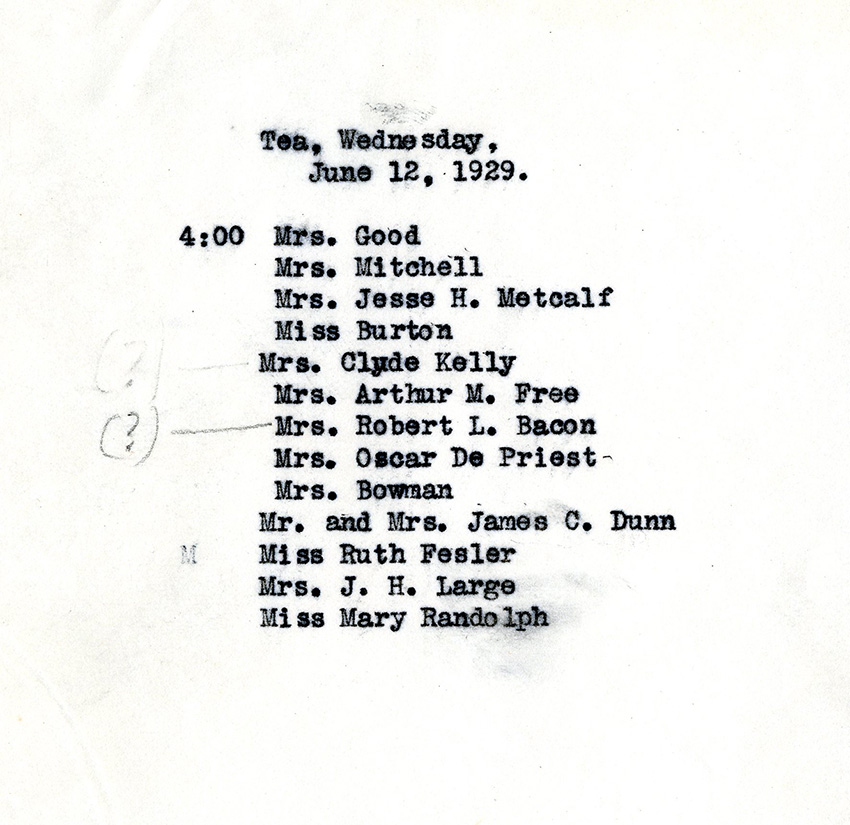

Tea with Mrs. DePriest Smallest of Four Teas

An average of 150 guests were invited to each of the teas held between May 27 and June 4. By contrast, the June 12 tea was a small, intimate group of 14 people, all of whom had presumably been asked in advance if they would be amenable to attending a tea with a black woman. The group consisted of the wives of some of Hoover’s cabinet members; three wives of members of Congress from New York, Pennsylvania, and California; Lou’s sister, Mrs. Jean Henry Large; and Lou’s personal secretary, Ruth Fesler. The menu consisted of tea, punch, sandwiches, and cake.

Several women changed their schedules to attend. Attorney General Mitchell’s wife, Gertrude, delayed a planned departure from Washington until Thursday. Lorna D. Sharpe Metcalf, the wife of Rhode Island senator Jesse H. Metcalf, responded to the invitation: “My dear Miss Polly [Mary Randolph’s nickname], Will be delighted to go to the White House tomorrow. I regret that I may be a few minutes late as I have asked some women for lunch and a sail which was to have terminated at 4, but I will try to cut it short and will get there as early as possible.”

Jessie DePriest arrived without fanfare at the White House on Wednesday, June 12. She was fashionably attired in an afternoon dress made of blue chiffon, and she wore a gray coat trimmed in moleskin, a small gray hat, gray stockings, and snakeskin shoes. Her attendance as an invited guest at a White House social function accorded DePriest a social legitimacy that other official Washingtonians had denied her. Lou Hoover’s invitation also, by extension, put a stamp of legitimacy on Congressman DePriest.

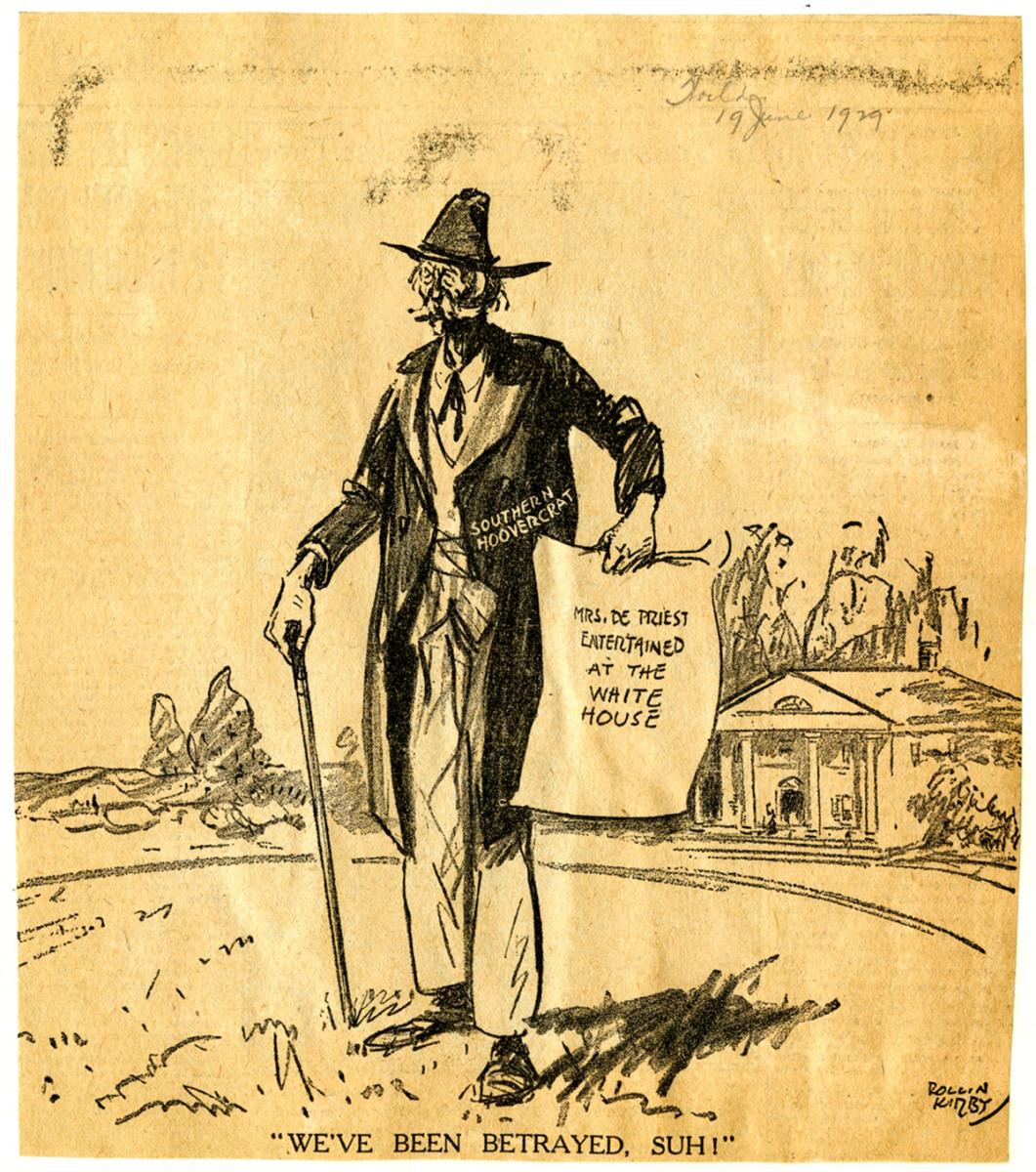

Within 24 hours, the event had become national news, and all hell broke loose. “Washington social circles buzzed excitedly Thursday when it became known that the wife of Oscar DePriest, Negro congressman from Chicago, was among the guests entertained at a tea Wednesday afternoon at the White House by Mrs. Hoover,” several newspapers reported.

White House Flooded With Hostile Telegrams

The initial telegrams that poured into the Executive Mansion sought verification of the story. Many of them were typical of this one sent from a committeeman from the second congressional district of Virginia, who wrote Lou: “Please wire me if Southern papers are correct in their morning statement that you entertained a Negro woman at tea yesterday. I have been a lifelong Democrat, but stumped the entire state of Virginia for Mr. Hoover last fall. We are to hold a semi-[R]epublic[an] convention in Roanoke, Va., June eighteenth. Very important I have your reply to read to this convention.”

Lou’s immediate reaction was to forward the telegram to her husband’s staff. Referring to herself in the third person, she asked:

Will you take this up with the President at the first opportunity? And report back to us as soon as possible.

We realize that “Mrs. Hoover” is perhaps not the one to make the statements in the questioned paragraphs. But perhaps it would be wise if those facts should get across by somebody else?

The White House immediately sought to limit the political damage. To fend off the charges that Mrs. DePriest had been granted social equality (which, of course, she had), Hoover’s press office insisted that Mrs. Hoover’s teas were simply official events, and not social ones. “It has been the custom for years for the White House to entertain at official receptions the wives and members of the Senate and House of Representatives in accordance with official lists furnished by the printing clerk of the Senate and the clerk of the House. No names have been omitted from the official list.”

Two days later, on June 16, Walter Newton released another statement: “The incident was official, not social,” and to have snubbed Mrs. DePriest would have been an act of “official discrimination” by the White House. Newton then provided a list of all the other times African Americans had been entertained socially at the White House.

This list included President and Mrs. Cleveland hosting Frederick Douglass and his white wife to dinner; Theodore Roosevelt inviting Booker T. Washington to dine with Roosevelt’s family; and the Wilsons hosting the Haitian minister, Solon Menos, and his wife, at five different diplomatic functions between 1914 and 1917. What was carefully omitted from this recounting was that Douglass’s visit had been loudly criticized by Southerners, and the rancor and racial hatred generated by Booker T. Washington’s dining with the Roosevelt family reverberated for years following the event.

Congressman Uses Tea to Further His Causes

However, the White House’s line of argument gained some traction. Some Southern newspapers echoed the White House explanation, insisting that Mrs. DePriest was only being recognized in an official capacity and not as a social equal.

Moderates attempted to tamp down a rapidly growing anger toward the Hoovers for giving any type of recognition to the DePriests. The Virginian-Pilot printed an editorial on June 16 that called for all “level-headed Southerners” to recall that the “Caucasian race did not suffer impairment to its security” following Theodore Roosevelt’s dinner with Booker T. Washington. The editorial followed the White House line and excused Mrs. Hoover’s behavior on the grounds that she was performing an official function and that “hell-raisers are always ready to scent social danger where no social danger exists.” The chair of the women’s division of the Memphis Hoover Club announced that Mrs. DePriest was not specifically invited to the White House. She came because all the wives of the members of Congress had been invited to tea and no names had been omitted from the list.

As the story was repeatedly retold, it began to be muddled, and newspapers added their own spin. A Tampa, Florida, newspaper insisted that the facts reported regarding the DePriest tea were part of a conspiracy of the “wet press” to arouse sentiment in the south without a just cause. Mrs. DePriest did not actually enter the White House, according to this report, but was served on the White House lawn with approximately 50 other guests with whom she did not mingle.

Overall, national outrage seemed to be short-lived and it looked as if the White House response would work. But the Hoovers and their political aides had not factored in Oscar DePriest’s decision to use the tea as an opportunity to further the cause of black equality. He understood that he represented ot only Chicago’s South Side but every aspiring African American in the United States as well. The tea provided DePriest with a national voice, and he used it.

In his statement to the press, DePriest said he was “immensely gratified” that his wife had received social recognition from the White House. “My wife enjoyed the experience and the social contacts very much,” DePriest commented. “She was treated excellently and there was no indication of a desire to discriminate in her case. Naturally, she is very much pleased with the whole affair.” Then, on June 16, DePriest announced his plans to hold a “black and tan” musicale and reception on June 21, on behalf of the NAACP, with the goal of raising $200,000. The money would be used for political lobbying on behalf of African Americans.

DePriest issued an invitation to all congressional Republicans but pointedly excluded two members of the party caucus: George Pritchard, who had refused to take an office next to DePriest’s; and Albert H. Vestal, of Indiana, whose wife had opposed Jessie DePriest’s membership in the congressional wives’ club.

DePriest’s planned fundraiser reignited the embers of the simmering racial anger. Segregationists were willing to dismiss Lou Hoover’s invitation to Jessie DePriest as long as it was simply an official act, but when DePriest used the opportunity to raise funds to promote racial equality, then the tea became a symbol of support for his actions.

The statement of Democratic Congressman Tilman B. Parks of Arkansas to the Arkansas Gazette summed up segregationist attitudes: Inviting Mrs. DePriest to the White House would “only lead to further activities of DePriest who is pushing himself forward at every opportunity. . . . Southern Democrats do not like his presence in the House of Representatives and the privileges he has taken.”

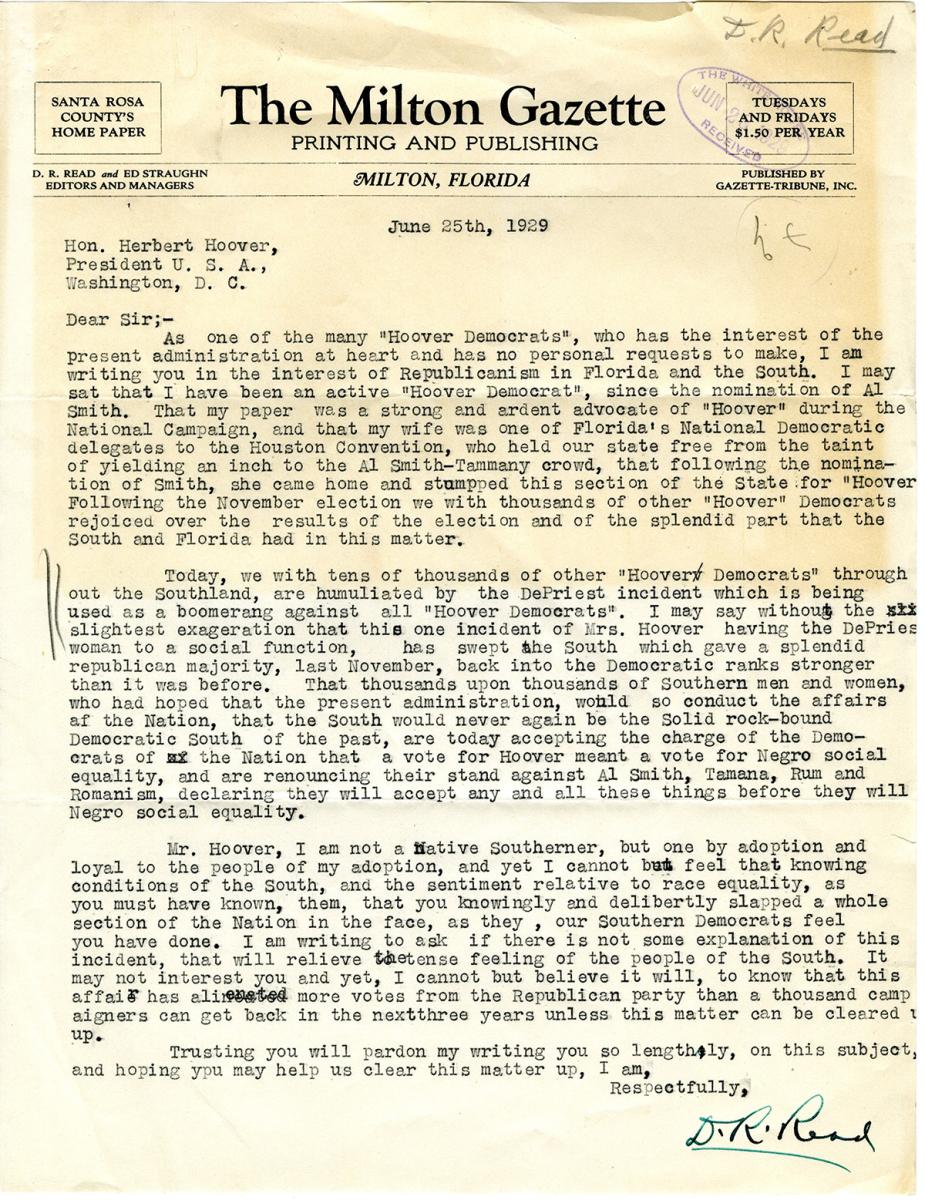

Letters addressed to President Hoover now poured into the White House from angry whites who had voted for him and felt betrayed.“I desire to unequivocally condemn the action of your wife who has brought about your downfall by inviting the wife of the Negro congressman DePriest to a White House tea. The constitution guarantees political equality, but it has never guaranteed nor advocated social equality with the Negro race.”

Another correspondent, originally born in Illinois and living in Florida, who described himself as a longtime Republican, told Hoover: “I cannot stand for Negro equality.”

Anger Surfaces Around Country

The Texas legislature voted on June 24 to formally censure Lou Hoover for inviting Jessie DePriest to the White House. The censure made national news, and the state’s former governor, O. B. Colquitt, urged the current governor, Dan Moody, not to sign the resolution. Colquitt, a member of the United States Board of Mediations, charged that the legislature had been misinformed and that the First Lady had acted in accordance with established official and personal custom.

“The rule is that there shall be no discrimination among persons whose membership in an official body is determined by the electorate or by their positions as representatives of foreign governments,” Colquitt noted. Moody split hairs in his decision: He disapproved those parts of the resolution that reflected personal criticism of Mrs. Hoover, but he “heartily approved” the section that condemned bringing the two races together on the same social plane. A woman from Austin sent a clipping of the article regarding the Texas decision, along with her calling card, to Lou. On it the correspondent wrote: “Texas is so disappointed in you.”

On June 27, the Georgia legislature voted 179 to 5 on a resolution declaring its “regret over recent occurrences in the official and social life of the national capital, which have a tendency to revive and intensify racial discord.” The Mississippi state senate “unreservedly” condemned Mrs. Hoover for entertaining Mrs. DePriest at tea. The Florida legislature passed a resolution condemning Lou for hosting a black woman in the White House.

The anger and dismay at Lou’s hospitality were not limited to Southern sectionalism. A state senator from Iowa, the state where both Lou and Herbert Hoover were born, wrote to say that many of his constituents “deplored the matter, but that Mrs. Hoover was compelled to do just what she did.” It was “one of the penalties she must suffer for being First Lady.”

Lou received some support for her decision from independent groups. The International Club of Detroit wired President Hoover on June 30 with the message: “Your hospitality to the DePriests commendably upholds the spirit of the 14 amendment and meets the hearty approval of the International Club of Detroit.” The Woman’s International League for Peace and Freedom commended Lou for extending Mrs. DePriest the courtesy of an invitation.

Support for Lou Hoover Found in North, Midwest

Lou saved the editorial from The Nation, which congratulated her “for the human decency of her act and for the dignified silence she has maintained since.” She wrote in the margin above the magazine’s masthead: “As you know [the editor] is a grandson of William Lloyd Garrison, the great Abolition editor. I think I told you I presided at a banquet in his honor here about a year ago.”

Northern and Midwestern newspapers wondered what the uproar was all about.

“The entertainment of the wife of the one Negro member of Congress at the White House caused a lot of needless excitement,” wrote a columnist for the Philadelphia Ledger on July 4. “There is nothing unusual about a member of the colored race being a guest at the President’s mansion.”

A writer for the Des Moines Register drew a distinction between Roosevelt’s choice to invite Booker T. Washington to the White House and Lou’s social obligation to extend an invitation to Jessie DePriest. “The present White House host had to include the wife of the Negro congressman in some one of the series of teas—or else be guilty of a discrimination so wanton that it would be construed an injustice.” The Chicago City Council passed a resolution calling Lou Hoover’s act “courageous,” and the national black press spoke in glowing terms of Mrs. Hoover’s decision.

The controversy continued to drag through the newspapers throughout the summer months. Some of the fires were flamed by the national speaking tour that Oscar DePriest embarked upon. He ignored death threats and traveled through the South, charging the segregationists with cowardice and working to raise money for the NAACP.

Not even “Black Tuesday,” the crash of the stock market on October 29, 1929, could finally put the DePriest story to bed; it was still being mentioned in December.

The level of anger expressed at the invitation extended to Mrs. DePriest reflects how deeply divided the nation was racially, and the Hoovers’ attitudes mirrored that schism. Other than Hoover’s decision to integrate the ranks of the Census Bureau, he did very little to further the cause of black people.

Lou Hoover Continues Support For Young, Black Women

In his 1922 book, American Individualism, Hoover had maintained that whites of Western European descent were intellectually and physically superior to other races—a view he supported based on his years as a mining engineer working with native populations in China, Australia, and on the African continent.

Lou’s racial views were more nuanced. Her high school class photograph shows a black male student, and her diaries contain occasional, matter-of-fact references to “colored girls” whom she met during her time at Normal School (teacher’s college) in Southern California. Lou’s letters from her years of living in China and visiting Japan contain some of the typical pejorative terms Americans used for citizens of those countries, and a letter written in 1932 to her son, Allan, contains anti-Semitic language when she referred to something written by columnist Walter Lippmann.

Nevertheless, as a member of the national board of the Girl Scouts, Lou had participated in the development of a policy that encouraged the formation of black Girl Scout troops, although they were segregated, and Lou secretly sent money to individual young black women so that they could pay for college during the Depression.

The political fallout from the DePriest incident hung over the remainder of the Hoover administration. As the economy increasingly faltered, and Hoover turned to Congress to ask for legislation to give relief, he found himself dealing with a branch of government little interested in working with him. The Democrats gained control of the House in the 1930 midterm election, and Southern Democrats used their power to block many of Hoover’s initiatives.

By the time 1932 rolled around, Hoover was looking for votes wherever he could find them. That included the African American voting community. In a speech delivered on October 1, 1932, five weeks before the upcoming election, Hoover asserted that the Republican Party could “speak with justifiable pride of the friendship of our party for the American Negro that has endured unchanged for 70 years.”

Hoover was soundly defeated in November 1932. Oscar DePriest was reelected again in 1930 and 1932 but lost his bid for a fourth term in 1934. By then, the Democratic Party had successfully built a coalition with African American voters.

After Mary Randolph resigned at the end of May 1930 (primarily for health reasons), Lou never hired another social secretary. Although she expanded the social calendar during her tenure in the White House, the series of teas that Lou hosted in 1929, which caused such a political tempest, were the only official teas she gave for congressional wives during her entire time as First Lady.

Annette B. Dunlap is a two-time Hoover Presidential Scholar and is currently at work on a biography of Lou Henry Hoover. She is the author of a biography of First Lady Frances Folsom Cleveland and of the forthcoming biography of Charles Gates Dawes, to be released in August 2016.

Note on Sources

The primary sources used for this article were the letters received by President and Mrs. Hoover, memorandums written by Mrs. Hoover and her staff, and news clippings that are part of the Lou Henry Hoover Archive at the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library in West Branch, Iowa. Newspaper articles related to Oscar DePriest’s earlier career are from Chronicling America, the historic newspaper site maintained by the Library of Congress (chroniclingamerica.loc.gov). Additional material on Oscar DePriest was found on the website maintained by the U.S. Congress on its members and on the history of the U.S. House of Representatives (bioguide.congress.gov and history.house.gov).

PDF files require the free Adobe Reader.

More information on Adobe Acrobat PDF files is available on our Accessibility page.