A Fortune in Gold (Dust)

How a Seattle Assayer Skimmed a Klondike Fortune

Spring 2015, Vol. 47, No. 1

By Luci J. Baker Johnson

© 2015 by Luci J. Baker Johnson

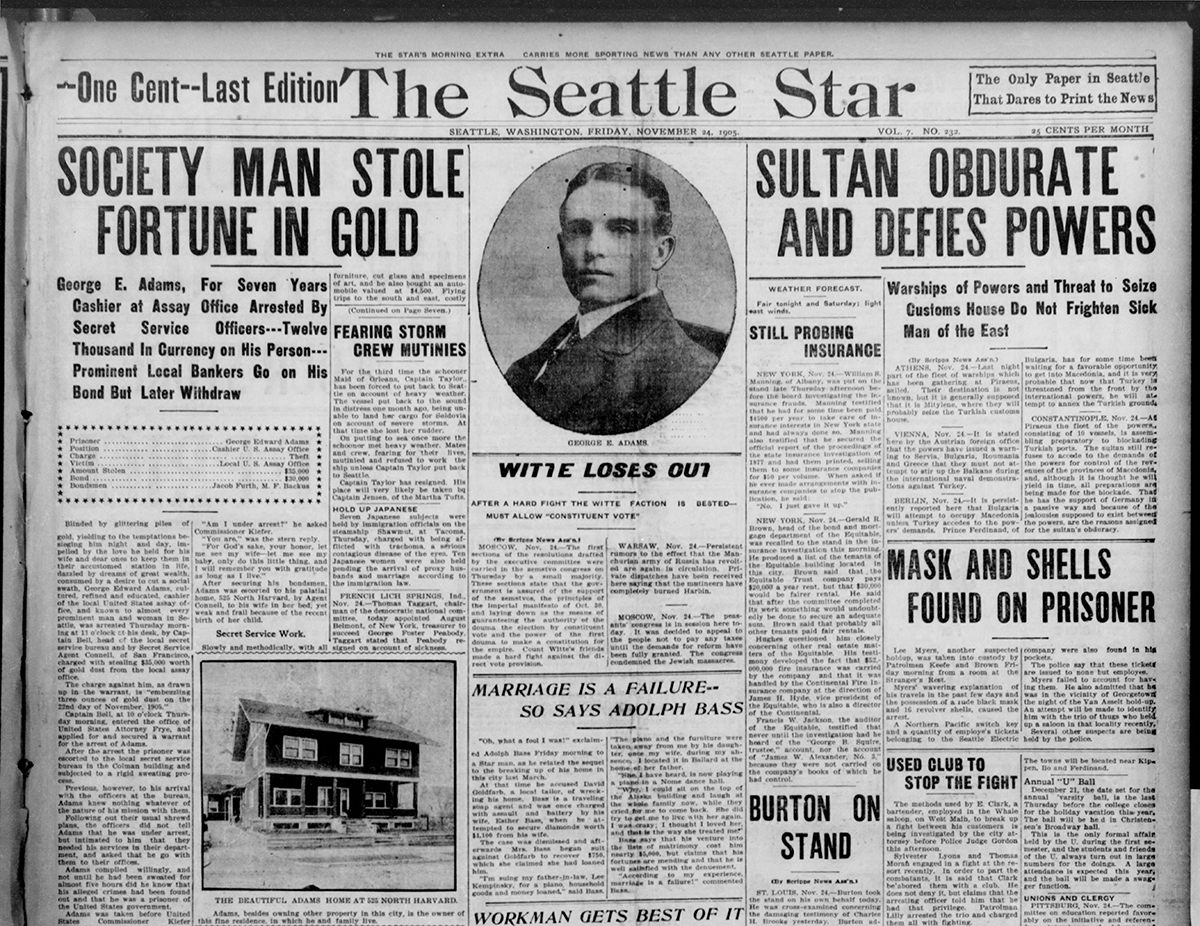

On Friday evening, November 24, 1905, this banner headline splashed across the front page of the Seattle Daily Times and shocked residents of Seattle, Washington: “CASHIER OF U.S. ASSAY OFFICE STOLE $200,000!”

Just below the fold was a large portrait sketch of George Edward Adams, the Seattle clubman U.S. Secret Service agents had taken into custody the previous evening. The newspaper’s entire front page focused on Adams’s arrest: “Extended Thefts,” “Adams in County Jail,” “Was a Defaulter Eight Years Ago.”

The stories carried over to page 2: “Charges of Theft Made Months Ago” and “Wilkie Talks of Assay Office Scandal.” Articles featured photographs of Adams’s home in a fashionable residential district and of the U.S. Assay Office. “Society Man Stole Fortune in Gold,” said the Seattle Star. And from the Wenatchee Daily World: “Cashier of U.S. Assay Office Steals Big Sum—George Edward Adams Arrested for Stealing Gold Dust from Miners—Adams Lives in Sumptuous Home and has Spent Money Lavishly.”

It didn’t end there.

The “shocker” spread across the country, much as news of the Klondike gold rush in the Yukon had spread, nine years earlier. The San Francisco Call reported, “Loots Gold Dust from the Miners—Cashier in a Seattle Office Admits the Theft of $35,000 When Arrested by Government Officers.” The Minneapolis Journal headlined, “George Adams of U.S. Assay Office Confesses to Pilferings of More than $30,000.” The news reached the East Coast: The Washington Evening Star screamed “Fraud in the Assays—How Cashier Adams at Seattle Stole $35,000.”

Just who was this George Edward Adams, the man federal investigators had determined had skimmed off a fortune in gold from the riches that miners had brought in from the Yukon?

At the time of his arrest, Adams was a trusted employee of the Seattle Assay Office, where miners could exchange the results of their work for legal U.S. currency, right on the spot. His federal personnel file shows that he had been appointed clerk of the Seattle Assay Office in July 1898 for four dollars a day. By October 1900 he was making six dollars a day.

An influential friend and mentor, Frederick A. Wing, had helped him to secure his position. Adams had worked for Wing as a teenager in Wing’s dry goods store in Hastings, Nebraska. Both eventually headed west, Wing to Seattle, where he became active in Republican politics, and Adams to Seattle, then Portland, where he was cashier for the Mutual Benefit Life Insurance Company of Newark, New Jersey. Wing persuaded Adams to resign this job, come to Seattle, and work for him again.

In 1898, Congress approved establishment of an assay office at Seattle. President William McKinley appointed Wing as assayer in charge on June 17, and the office officially opened for business July 15. During its first four months after opening for deposits, the office received $5,478,549.75. It was soon the second largest assay office in the United States after the New York office.

“Leading a Crooked Life” as Youth in Massach

Adams was now in a job that would bring him fame and fortune—but also shame and notoriety—in a part of the country far from his New England birthplace.

Adams was born in East Pepperell, Massachusetts, about 60 miles from Boston. His birth record shows that he was born on March 5, 1868, although in some legal records Adams gives 1872 as his birth year.

George’s father, Robert Adams, and his two brothers all enlisted in the Union Army and served to the end of the Civil War. Just after the war, Robert studied for the clergy. After several years in New York State he was transferred to Nebraska, where he became a pioneer preacher. If we are to believe George Adams himself, he “began leading a crooked life” when he was 13 years old. In a Sunday newspaper article he penned from prison in 1908, Adams wrote, “though I have touched as much as $500 in a week, at other times I have been practically penniless.” He then recalled various cons that he and his young cohorts ran on unsuspecting victims, parting them from their hard-earned money.

Shortly after Adams was arrested in Seattle, he spoke with a reporter from the Seattle Star, which was published on December 5, 1905. At this point, Adams had spent 12 days in the King County jail, in the company of hardened criminals who were charged with significantly more violent crimes.

“All I want is a square deal,” Adams was quoted in the Star’s article. “People nowadays are only too willing to kick a man when he’s down. Why, I wouldn’t do that to my worst enemy.”

He continued, “Well, I’ll tell you. I’ve done nothing so far to be ashamed of. . . . My mother is dead. My father lives in Johnsburg, near Saratoga, New York. I have two brothers and a rich uncle in New Amsterdam, New York. . . .

“When I was still a boy I left home, because I had to make my own living, and went west. For about two years I did odd jobs in southeastern Nebraska, and then went to Hastings, Nebraska, where I was employed as cashier in a dry goods store. But previous to that I went to the Wesleyan university, which was then at Osceola, but is now at Lincoln. I graduated second in my class from that college.”

Some of this, the part about his family, can be verified. Regarding Wesleyan University, however, attempts to verify have failed to confirm either his attendance or his graduation.

“When I was 20 years old, I gave up my job in Hastings and came to Seattle. That was in 1890. . . . The first job I got was as a receiving teller in the Merchants National Bank. . . . I married here, always led a temperate life and flatter myself that I am considerably better educated than the average man. . . . And all this I’ve done myself, with no man’s help. . . . That’s the story of my life. Is there anything criminal about it?

Adams clearly stretched and edited the truth, at best, when telling his own story. He held other positions of trust between his job as a Seattle bank teller and his role at the assay office. He also seems to have been given a number of second chances, often involving Frederick Wing.

In 1897, Adams was cashier for the Massachusetts Life Insurance Company, whose Washington State office was in Seattle. Wing was the company’s agent for the state. Adams reported to the company’s head office, and although Wing had not appointed him as cashier, Adams was nevertheless directly under Wing’s charge.

About the time of the Klondike gold rush in the late 1890s, Adams set out to organize and equip an Alaska steamship company. In trying and failing to float this company, he used between $5,000 and $10,000 of insurance company money entrusted to his care. The company finally noticed the irregularity and sent in an auditor, who discovered a $5,000 shortage.

A Venture Goes Sour, A Call from an Old Boss

A promise was made to him that if he made good the shortage, he would not be prosecuted. With the help of friends he raised the money and repaid the company. He told his friends that he had had no intention of stealing the money, and that had an Alaska steamship venture panned out as he had hoped, he would have returned the money at once and had many thousands of dollars in profit.

Only a few friends knew this embezzlement story. When he squared the amount, no one cared to injure him by making the affair public. The Massachusetts Mutual Company dismissed him at once, however. Adams was later made cashier of the Mutual Benefit Life Insurance Company of Newark and placed in charge of its Portland, Oregon, office. As far as is known, he attended to his business there in an honorable manner, but Adams had not been in Portland long when Wing persuaded him to join him at the assay office in Seattle.

By 1905, George Adams was an up-and-coming society man, well known and respected among Seattle’s crème de la crème. He held prestigious positions as clerk, then cashier, for the Seattle Assay Office. He educated himself in numismatics and also studied the placer mining processes used in Alaska and the Klondike.

Adams was a skilled writer, and one of his articles, for the November 1900 issue of The Cosmopolitan, an illustrated monthly magazine, was titled “Where the Klondike Gold is Valued.” The article extolled the good works of the Seattle Assay Office and included a dozen photographs taken in Seattle and the Yukon. The caption for one photograph, which showed a dozen men standing and sitting on large crates, read “A Million Dollars Worth of Klondike Gold-Dust.”

Another situation developed in the summer of 1900.

On July 5 two brothers—miners from Dawson, Yukon Territory—arrived, late in the afternoon, at the Seattle Assay Office. They had recently returned from the Klondike and presented several pokes (small sacks) full of gold dust. The weigh clerks weighed the dust, which came in at 233.93 ounces. This result was shown to the miner William S. Paddock, and he received a receipt for the gold dust. It was too late in the day to melt the gold dust, so it was given to the cashier, Adams, to put in the office vault for safekeeping.

The following day, the gold dust was passed to the melter and found to contain only 133.93 ounces. The value of this loss was $1,663.68. The Paddock brothers were not pleased, and demanded payment for the missing 100 ounces of gold. Adams denied having taken any of the deposit, and insisted that he had only received 133.93 ounces to put in the vault.

After much discussion, several officers and employees of the Seattle Assay Office, along with George H. Roberts, director of the U.S. Mint, contributed their own money to make up the loss, to protect both the government and its depositors. A check for $2,186.06 was delivered to Dexter, Horton and Co., a bank representing the Paddocks. This episode seems to have been Adams’s first theft from a gold miner’s deposit.

In an article published nearly three years after Adams’s 1905 arrest, the Portland Morning Oregonian reported that Adams “charges that in the settlement of the so-called Paddock Bros’ claim for 100 ounces of gold dust, supposed to have been lost in 1899 [sic], that the payroll of the office was ‘officially juggled,’ and that money returned on account of this claim rightfully belongs to him.”

Adams Marries into Society, But Suspicions Still Build

In his mid-30s, Adams was a small man, 5 feet 6¾ inches tall, 135 pounds. His complexion was fair and his hair light brown; his deep-set, flashing, dark blue eyes were his signature feature. He was always clean shaven, with a stern small mouth and a bulldog grip of the jaw. His manner of speech was refined and articulate. One reporter described Adams as having long, slender hands—able to extract an ounce of gold from a poke. “They are the hands, the police will tell you, of a pickpocket.” The Seattle Star of November 28, 1905, described him as blithe, debonair, natty, and cunning; crafty, calculating, cool, and careless of the consequences of his crime; and “seemingly calloused to the opinion of the world.”

Adams seemed to have an endless source of funds, spending them on vast amounts of real estate, expensive books for an elaborate personal library, oriental rugs, fine house furnishings that included cut glass and china, and the latest model automobile.

Co-workers wondered how a man on Adams’s limited salary could live in the expensive way he did. There was a rumor, which circulated around the assay office, that Adams had inherited some money from the East. Adams himself had once said that he had an inheritance from a rich banker uncle in New York State.

Adams’s marriage to a local society girl was a notable gathering of many from Seattle’s social elite. On November 16, 1904, he married Emily Stoddert Clary, the only daughter of Captain and Mrs. Charles Clary. Captain Clary had been United States bank examiner for Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana from 1892 to 1900 and was considered one of the pillars of the financial establishment in the Pacific Northwest. The couple’s honeymoon took them east for a nine-week cross-country journey ending in New York City. Within a short time they were expecting their first child. Their son was born on November 19, 1905, just four days before Adams’s arrest.

The Seattle Assay Office had a melting department and an assay department, so miners could be paid with a government check and the gold sent to Philadelphia to be turned into coins.

When steamships arrived at the port of Seattle, miners would disembark and make their way up the steep hill to the assay office at 619 Ninth Avenue, on Seattle’s First Hill. Long lines of miners would form to await their turn at the receiving window. Often these men, and sometimes women, carried their newfound gold dust in a poke, a small sack used to carry around gold dust and nuggets. It was often hand sewn, with a vertical seam running up the back, a round cup bottom with a horizontal seam, and a thong for a tie, which was sewn opposite to the vertical seam. Using these tightly sealed bags minimized gold dust loss.

In this form, gold dust carried a small percentage of fine black mineral sand, which miners could not remove from the gold dust without also washing out particles of gold associated with it. When the gold dust was melted into bars, this sand went off with the flux that separated impurities from the gold.

This meant that after the gold had been melted, it weighed less than the sand-bearing gold dust had weighed before melting. This loss was expected, but the weight loss during melting typically did not exceed 5 percent. This expected shrinkage was a known figure, used throughout the country in dealing with gold from Alaska or the Yukon. Whether it was weighed, melted, and assayed in Seattle, or in San Francisco, or even in Philadelphia, 5 percent was a reasonable and expected weight loss.

Authorities Prepare a Trap While Suspicions Remain

But there were rumors among gold miners and Alaska banks that something wasn’t quite right at the Seattle Assay Office. The percentage of losses there seemed to be greater than the average.

“In proving up our dust we would send samples to the mints at Philadelphia and San Francisco and to the Seattle Assay Office,” W. H. Parsons, manager of the Washington-Alaska Bank at Fairbanks told the Seattle Daily Times in February 1906. “When the reports came back, the ones from Philadelphia and ’Frisco would tally to a dot with our own assays, while with not a single exception the report sent back from the Seattle Assay Office would show a terrible Shrinkage.”

He went on to tell how his office “ran a systematic search from early July to late September [1905] to prove beyond question that there was a shortage in the Seattle Assay Office.”

This concern was expressed to the director of the Mint, George E. Roberts. Roberts assigned Frank A. Leach, superintendent of the San Francisco Branch Mint, to investigate the issue and report his findings to Washington, D.C. Leach took an assistant to Seattle with him: Lee S. Kerfoot, a bright young employee of the San Francisco Mint.

Kerfoot was a graduate of the College of Mines, University of California, with experience in the metallurgy of melting gold. Leach also enlisted the expertise of William J. Burns, a well-known independent detective, who assigned two men to run down the habits, past and present, of all employees who worked in the Seattle office’s melting room.

While Burns’s team investigated employees, Leach and Kerfoot conducted experiments and took notes on the melting room’s daily operations. They weighed and reweighed each deposit. Each workday’s total “shrinkage” losses were more than their experience told them to expect. It became clear to them that the gold theft was continuing, even while they were there and monitoring the process.

“The realization of this fact made us feel as if the fellow who was guilty of the dishonest work thought he was so shrewd and had his tracks so well covered that he could safely continue his stealing during our presence there, and was practically laughing in our faces,” Leach later wrote in his memoir.

After some thought, Leach recalled that “afternoon” deposits did not go directly to the melting room. Rather, the cashier stored these deposits in the vault overnight, and brought them to the melters the following morning. Leach calculated losses for the morning deposits and found them to be normal. Then he calculated losses for the afternoon deposits that had spent the night in the vault. These losses ran about 3 percent greater than they should have.

Adams was in the habit of coming to the office a half hour before the office opened. He said he did this to bring out the deposits kept overnight in the vault, to reduce delay in starting the day’s melting work.

Adams had been discovered!

Now Leach, Kerfoot, and the Secret Service needed to lay the groundwork for a sting operation to catch Adams before he could leave town.

Federal Agents Arrest Adams, Who Insists He Is Innocent

On that fateful day, Thursday, November 23, 1905, Kerfoot arrived at the office a couple of minutes after 9 a.m. and found the vault opened, with four gold deposits on the hand truck ready to be weighed. The morning’s events are recorded in Kerfoot’s testimony, as reported in the special master’s final report on cases #1364 and #1365 of U.S. v. George Edward Adams.

Secret Service operative Stephen Connell was stationed in a grocery store across the street with a clear view of the assay office entrance, waiting for a prearranged signal from Kerfoot. The stage was set.

A few minutes after 10 a.m., assistant melter Towne came to Kerfoot and whispered, “Mr. Wing just told me that George was called out of bed to the ’phone this morning and informed by Dr. Raymond [a family friend] that he [Adams] was to be arrested that day for stealing gold from the government. Adams himself had told Mr. Wing.”

Kerfoot sent Myers, one of the melters, to find Connell and tell him what was afoot. After Adams arrived, Kerfoot observed him seal some large envelopes and wrap several packages, one of which Kerfoot believed to contain a tin box from the vault that was of particular interest to the investigation.

At 11 a.m. Connell, accompanied by Bell and Harry Moffett of the Secret Service, arrived at the assay office and arrested Adams. In his testimony Kerfoot said, “I could not hear Mr. Connell’s first statement to Adams as he spoke very quietly, but I saw Adams turn to Mr. Wing and say, ‘Do you know what this means?’” Kerfoot said in his testimony.

“Adams was asked to produce the private box that he had kept in the vault. He led the officers to the vault, unlocked the door, entered and handed down from the top of one of the safes a locked tin box, saying, ‘There it is.’ This was not the box the officers had demanded. He was asked again, ‘Where is the red box that used to be set here, George?’ To which he answered, ‘I took that home last night.’ When asked what was in the box, he answered, ‘Private papers.’ He continued by saying that it was at his home at 572 Harvard Avenue and had not been opened since leaving the assay office.”

The officers then picked up the box of interest, which was sitting beside Adams’s desk, carefully tied in heavy wrapping paper. When asked to open it, Adams said the key to it was at his home. The officers took Adams prisoner at this point and bought him and his boxes downtown to Bell’s office.

Searching Adams himself, they found several large bunches of keys and several sealed envelopes, one of which contained $12,000 in cash. The officers then insisted that Adams open the red box. He finally did so with great reluctance, and the box was found to contain a set of scales with weights, plus eight to ten boxes of veterinary medicine capsules. Some capsules were empty, and some were partly filled with black sand. There were grains of gold dust and sand scattered over the scales and the bottom of the box, and in the holes used for storing weights in the box.

When questioned, Adams said that he had been interested in the abstraction of gold from the Nome Beach sand, and had conducted some experiments along that line. When the officers asked if he did these experiments in the vault, he answered, “No, I was carrying on this work several years ago and simply placed the scales in the vault for safe keeping.”

According to Adams, he had done this in April 1905. They asked if he had ever weighed gold dust on the scales, and he answered, “No.” When the officers pointed out the gold dust on the scales, he claimed to have misunderstood the question.

Secret Service officials continued questioning Adams for the next several hours while officers searched his home, his real estate holdings, and the garages where he stored his automobiles. The officers discovered $400 worth of stolen gold dust on his person and another $700 in gold dust in various pokes at his home. They also found a mortar full of sand, several more capsules, sealing wax, two sets of gold balances, several assayer’s spoons, and a large amount of stationery (writing paper, envelopes, and cards) all stamped with the name J. W. Harriman, Nome Alaska, Assayer & Chemist.

Adams had an explanation or excuse for every question posed to him.

Finally, near dinnertime, Adams confessed to the officers that he had stolen about $35,000 worth of gold dust from the assay office since the opening of the Alaska season in June 1905. He claimed that he had begun to steal when he needed money to make payments on land he had purchased, but that he had been unable to stop even after this need for ready money had passed.

He claimed not to know Harriman the assayer and chemist, and stated that someone whose name he did not know had left the chest containing the Harriman stationery at his garage several years earlier.

Adams Loses His Allies Despite Emotional Appeal

At about 6 p.m. Adams was taken to the U.S. commissioner’s office in the Seattle Colman building, where he was given a hearing and placed in the custody of U.S. deputies. His bail was fixed at $35,000. Adams pleaded for a smaller bail, saying he was very anxious to get home to his wife and baby, but the request was denied. Later that evening, however, two of Adams’s banker friends—Jacob Furth and Mason Backus—posted his bail. When Adams returned home, he kept all of this from his frail wife but got busy. He telephoned the editor of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, pleading that the affair be kept out of the newspaper, as he would “have the whole thing straightened out in a day or two.”

Friday morning, November 24, Adams gathered several men he felt had a vital interest in his case. These included his pastor Reverend Lloyd, Backus, Furth, Wing, Connell, and Kerfoot. Adams spent about an hour expounding on the circumstances that had led up to his dishonesty.

The aim of most of this talk was evidently to show his ability to make money. He showed articles he had written for magazines and drew attention to the money he had earned in doing so. He said that he had lived economically and invested his earnings profitably. He claimed that his grandfather had left him about $1,500 four years earlier, but admitted that his previous stories about other inheritances had not been true. He wept throughout this performance and claimed that his first dishonest act occurred about June of 1905. He finished by claiming that his mother-in-law had made his life hell, and that her continual demands for luxuries drove him to taking gold dust from the government.

When he concluded, his bondsmen revoked their offer of bail, and Adams was turned over to the deputies to be taken to the King County jail.

A thorough investigation showed that Adams had actually begun stealing gold dust shortly after he was appointed cashier at the Seattle Assay Office. His first documented gold theft was the 100 ounces stolen all at once from the Paddock Brothers in 1900, which was noticed quickly and raised an alarm. After this, he became much more careful. He devised a “nearly perfect” scheme for pilfering gold dust, limiting what he took from each poke to an amount small enough to avoid easy detection, and replacing it with exactly the same weight in black sand.

By 1901, he had begun to take about one-quarter of 1 percent of the gold from pokes that had been presented to the assay office in the afternoon and stored overnight in the vault for melting the next day. He would extract a small amount of gold dust (half an ounce to two ounces) from each poke, and replace the weight taken with black mineral sand, similar to that found in streams and beaches of the Alaska goldfields. The government’s investigation showed that for five years he had used a false name to purchase more than 800 pounds of this black sand from a vendor at Neah Bay, Washington.

He brought the black sand to the assay office in veterinary capsules, which were small and could easily go unnoticed. In the privacy of his home or garage, he would weigh out one ounce of sand into a capsule, hide it in his clothing, and bring it to the assay office.

During his half-hour before the office opened, and during his co-workers’ lunch, he would lock himself in the office vault and carefully extract gold dust from each poke. He used the scales to precisely measure the exact amount. He then put the stolen gold dust into small brown ”pay envelopes” and slipped these into his pockets. Once the envelopes were filled, he distributed them on his person and went about his day. This let him carry the gold away without inconvenience or discovery.

To convert the gold dust into funds he could spend or invest without attracting attention, Adams would travel once a year by train to San Francisco, carrying his pokes of gold dust in a typewriter case. He sold the gold at the Selby Smelting & Lead Company, using the false name “Markel.” He would hang around the office while the gold was being melted and glibly talk with employees, saying to the receiving clerk that he was on his way back East the very next day, so that he needed immediate payment for the gold in cash. He then returned to Seattle on an evening train.

After each trip, he deposited the cash into several bank accounts. He secured $18,564 for his stolen gold in 1901. His second trip was a bit larger, at $23,409, and in 1903 he obtained $17,255 for the gold dust he took to San Francisco.

Adams Emerges from Trial as Federal Prisoner #1706

Adams was booked at the King County jail, a few blocks from the assay office on First Hill. He spent nearly a year in jail while government officials investigated the extent of his theft and sought to identify his numerous victims.

Adams continued to plead his case to friends and associates. His wife believed his explanation and sought his release, but the government had another plan. In June 1906, Congress appropriated $12,000 to fund a special master whose task would be to determine how much gold Adams had stolen. Adams remained in jail, awaiting the outcome.

Special Master Will H. Thompson, appointed to take testimony and to make special findings of facts in the case of the U.S. v. George Edward Adams, conducted thorough investigation over the next several months. He posted notices in at least five newspapers in Washington, Oregon, and Alaska, asking people to come forward and submit claims for losses, and sent over 700 letters to potential victims. A total of 201 claims were made against Adams.

On November 14, 1906, Adams pled the charges down to two counts and was sentenced to two consecutive five-year terms at hard labor in the federal penitentiary at McNeil Island. He was also ordered to pay all the costs of the prosecution and stay in prison until the payment was satisfied.

The story of George Edward Adams does not end with his going to federal prison in November 1907.

While incarcerated, he impressed Warden O. P. Halligan enough to be assigned as the prison’s office clerk. He also became familiar with many other inmates, including Robert Stroud, later known as the Birdman of Alcatraz; Robert Hopkins, a former clerk of the federal district court and confirmed embezzler; and John G. Webber, an aged counterfeiter whom Adams befriended.

Adams was paroled in May 1912 but was arrested again in September 1912 for counterfeiting, along with Webber. Both were sent back to McNeil Island. Adams’s parole was revoked in June 1913.

He sought parole again, but was denied. Adams was finally released In November 1917 and the following day “assumed the duties as clerk at McNeil Island”—back on the federal payroll. Adams resigned his post in April 1922.

George Edward Adams—assayer, society man, twice-convicted felon—vanishes.

Luci J. Baker Johnson is a historian, freelance writer, and citizen archivist at the National Archives at Seattle, where she has been a weekly volunteer since 2000. She stumbled across the undiscovered story of the Seattle gold dust thief while writing the chapter on clubs and associations for the book Tradition and Change on Seattle’s First Hill: Propriety, Profanity, Pills, and Preservation (Documentary Media, 2014). Baker Johnson is on staff at Historic Seattle, a preservation development authority in Seattle, Washington.

Note on Sources

Primary sources consulted regarding George Edward Adams as a federal employee are found in Records of the U.S. Civil Service Commission (Record Group [RG] 146); the Records of the U.S. Mint, 104.5.12 Records of the Assay Office, Seattle 1898–1955 (RG 104); and Publications of the U.S. Government, 1790–1984, The Official Register of the United States, 1816–1959 (RG 287).

Information pertaining to the Secret Service investigation, the arrest, and the civil and criminal case records were gleaned from the following National Archives record groups: Records of the U.S. Secret Service, 1863–1988 (RG 87); General Records of the Department of Justice, 1790–1989 (RG 60); Records of District Courts of the United States, Western District of Washington, Northern Division, Seattle District Court, Civil and Criminal Case Files (RG 21); and Records of the Bureau of Prisons, 129.8 Records of the U.S. Penitentiary, McNeil Island, Washington, 1881–1981 (RG 129). Additional information about the case was discovered in Records of the Office of the Pardon Attorney, Pardon Warrants, 1893–1936 (RG 204). The Special Masters investigation and official report were extremely valuable and extensively detailed.

This article benefited by the several, if contradictory, accounts found in published memoirs. In 1919 Frank A. Leach completed his memoirs, covering what he described as a life experience of 65 years in California. His Recollections of a Mint Director (Wolfeboro, NH: Bowers and Merena Galleries, 1987) has an extensive chapter on the gold-dust theft. An additional resource is a recently published book, Looking Outward: A Voice from the Grave (Springfield, MO: Looking Outward, LLC, 2013) by Robert F. Stroud (a.k.a. Birdman of Alcatraz), in which the author alludes to his interactions with Adams.

Also referenced were pieces written by Adams and published in Harper’s Weekly, June and August 1900; The Cosmopolitan Magazine, November 1900; the Seattle Star, December 1905; and the Seattle Sunday Times, November 1908 and November 1910.

Genealogical information was also accessed while researching Adams’s life. Sources consulted included, but were not limited to, records from the National Archives, Bureau of Census: New York, Nebraska, and Washington (RG 29); State and Territorial Records—New York, Nebraska, Washington Territory, and Washington State; the Washington State Vital Records; and Seattle City Directories (1890–1925).

Second only to the records from the National Archives were news articles from over 40 newspapers from across the country: Alaska, California, Idaho, Minnesota, Nebraska, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Utah, and Washington (1893–1918). Access to this treasure trove of information came primarily from the Library of Congress (www.chroniclingamerica.loc.gov); California Digital Newspaper Collections (www.cdnc.ucr.edu/cgin-bin/cdnc); Historical Oregon Newspapers (www.oregonnews.usoregon.edu); American GenealogyBank; and lastly but most significantly, the Seattle Times Historical Archives resource (1900–1984), whose existence is made possible through a generous grant from the Seattle Public Library Foundation.

The author is grateful to the following individuals for their assistance and advice in retrieval of primary and secondary source records: Glenda Pearson, head of Microfilm and Newspaper Collections, University of Washington; John LaMont, genealogy librarian at Seattle Public Library; and Ken House, archivist, National Archives at Seattle.