Mr. President

How Judgments of Eisenhower in the White House Have Changed

Fall 2015, Vol. 47, No. 3

By Irwin F. Gellman

© 2015 by Irwin F. Gellman

The following excerpts are from The President and the Apprentice: Eisenhower and Nixon, 1952–1961, by Irwin F. Gellman, published this summer by Yale University Press.

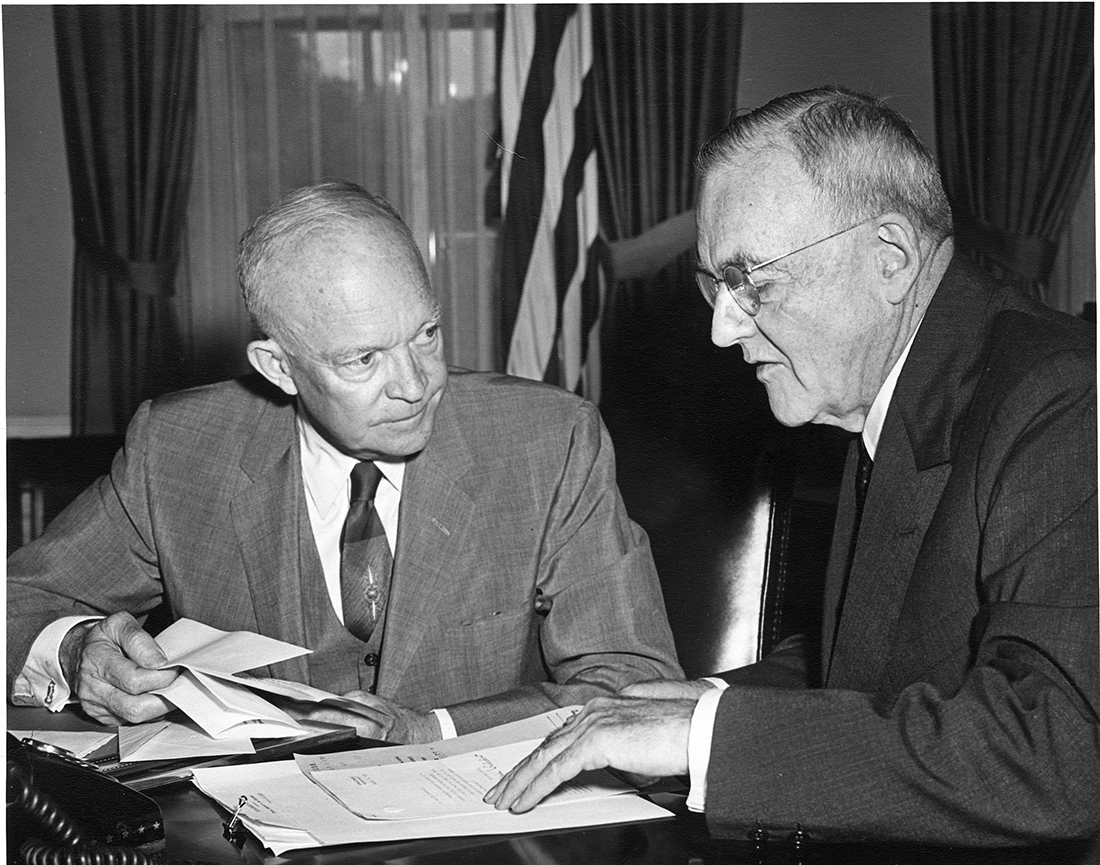

Ever since the 1952 presidential election, authors who opposed Dwight Eisenhower on philosophical and political grounds have dominated the discussion of his White House years. At the same time, a number of misconceptions about those years have gone unexamined. For too long, the fable that Eisenhower spent more time playing golf than governing was accepted as fact. It was said that Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, for example, shaped American diplomacy and White House chief of staff Sherman Adams took on such an outsized management role that he earned the title assistant president. In reality, Eisenhower formulated foreign policy in the Eisenhower administration; Secretary Dulles dutifully carried out Ike’s directives. Eisenhower was a skillful, hands-on President (he had, after all, overseen the invasions of North Africa, Italy, and France during World War II) who set his own agenda. Adams managed the President’s schedule and protected him from unwarranted intrusions, but did not act for him or enforce his decisions.

Historical consensus has been especially unkind to Richard Nixon, who is thought to have played a minimal role as Vice President, in an administration that accomplished so little that there was not much for a Vice President to do. Besides, the President neither depended on nor liked Nixon. The reality is that the President and his apprentice respected and trusted each other. Nixon was deeply involved in many far-reaching initiatives and emerged as one of the most important presidential advisers.

The negative portrayals of Eisenhower began before he became President and changed slowly after his death. After World War II, both major political parties tried to draft him as their presidential nominee. He refused and in 1948 accepted the presidency of Columbia University. Many faculty members, especially those in the social sciences and the humanities, considered a military man unsuitable to lead the university, and throughout his tenure the complaints, ranging from petty to serious, grew more vocal and intense. Historian Travis Jacobs, in his book Eisenhower at Columbia, wrote: “Some faculty members criticized Eisenhower because he did not seem interested in the academic needs of the university, but their major complaint was that he never was a full-time President due to his failing health and extensive travel schedule.” Neither posed any threat to his tenure.

During the 1952 presidential campaign, the faculty and staff split into warring camps: those who supported the Democratic candidate, Adlai Stevenson, and others who backed Eisenhower. According to reports in the New York Times, some grew so hostile that they refused to talk to colleagues on the other side. After Ike’s convincing triumph, some Stevenson loyalists refused to accept defeat and used undergraduate lectures, graduate seminars, and writings to trivialize the winner.

They remained unconvinced after Eisenhower defeated Stevenson again in 1956. Columbia historian Richard Hofstadter, in Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, described Ike as having a “conventional” mind and “fumbling inarticulateness.” William Leuchtenburg’s 1993 book In the Shadow of FDR (written after he had decamped from Columbia for North Carolina) provided a negative assessment of Eisenhower’s presidency, stating that he left the Oval Office with “an accumulation of unsolved social problems that would overwhelm his successors in the 1960s.”

Up at Harvard, historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., who worked on Stevenson’s staff during the 1952 and ’56 campaigns and would later be a special assistant to President John Kennedy, charged that Eisenhower had accepted McCarthyism “with evident contentment.” Throughout his career, Schlesinger regularly belittled Eisenhower. As late as 1983 he described the former President as “a genial, indolent man of pied syntax and platitudinous conviction, fleeing from public policy to bridge, golf and westerns.”

In his prestigious Oxford History of the American People, published in 1965, Samuel Eliot Morison used his chapter on the Eisenhower years to highlight the President’s failures: “Peace and order were not restored abroad; violence and faction were not quenched at home.” The former President received a copy of the book and scribbled on the dedication page: “the author is not a good historian. . . . in those events with which I am personally familiar he is grossly inaccurate.”

Morison co-wrote with Leuchtenburg and Henry Steele Commager (also a Columbia professor until 1956) a widely assigned college textbook, The Growth of the American Republic, in which the authors downgraded the Eisenhower presidency with a backhanded compliment: “Eisenhower had made an important contribution toward unifying the nation, but not a few asked whether the price that had been paid was too high.”

The academic criticism was not limited to Cambridge and New York. Before Ike’s first term was finished, Norman Graebner, a diplomatic historian at the University of Virginia, argued that the President was returning the United States to a “New Isolationism.” Several months before Ike left office, Graebner concluded that the President’s advocates had “measured his success by popularity, not achievements.” Two years later, in the preface to an edited volume of chapters by well-known authors, historian Dean Albertson wrote that “informed reaction to the Eisenhower administration was unfavorable.”

Many journalists criticized Eisenhower for his lack of leadership. Marquis Childs, a syndicated columnist, enumerated his subject’s weaknesses in his 1958 book Eisenhower: Captive Hero. New York Times reporter James Reston found in Ike a symbol of the times: “Optimistic, prosperous, escapist, pragmatic, friendly, attentive in moments of crisis and comparatively inattentive the rest of the time.” Columnist Richard Rovere summarized Ike’s lackluster achievements: “The good that Eisenhower did—largely by doing so little—was accomplished . . . in his first term.”

Political scientists painted their own unflattering portraits. James Barber, who analyzed presidential performance according to a four-part matrix—active/positive, active/ negative, passive/positive, and passive/negative—put Ike in the last box and asserted that he left “vacant the energizing, initiating, stimulating possibilities” of his office. A counselor to John Kennedy during his congressional years, Harvard professor Richard Neustadt, used 160 pages of his 1960 book on presidential power to enumerate how poorly Eisenhower had governed.

In the 1960s, Eisenhower responded to his detractors with two volumes of memoirs, The White House Years, in which he defended his record on such controversial subjects as Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy and his refusal to aid Britain and France during the 1956 Suez invasion. Those recollections and later books by close associates—such as Sherman Adams’s Firsthand Report and Ezra Taft Benson’s Cross Fire—emphasized the administration’s achievements. Attorney General Herbert Brownell, Jr., years later, commented in his memoirs: “There was never any doubt in the Eisenhower administration about who was in charge and who made the decisions. The President did.”

Such testimonials did little to overcome the consensus on Ike’s mediocrity. The fiction that Eisenhower had governed incompetently, and that he had failed to use the bully pulpit effectively, continued to be accepted without careful analysis. This impression still lingers.

Cracks in the concrete began to appear when the well-respected journalist Murray Kempton wrote in the late 1960s that pundits had underestimated Eisenhower’s acumen. After the Dwight Eisenhower Presidential Library opened in the spring of 1962 and the National Archives started to release thousands upon thousands of administration documents, Herbert Parmet became one of the first historians to examine them and was surprised by what he uncovered. His Eisenhower and the American Crusades, published in 1972, represented the first time a serious scholar suggested that Eisenhower had accomplished far more than previous writers had allowed.

Others followed. In the early 1980s, political scientist Fred Greenstein examined the recently opened files of Ann Whitman, the President’s private secretary, and determined that Ike had employed a “hidden hand” to manage the federal bureaucracy. In The Hidden-Hand Presidency and Presidential Difference, Greenstein elaborated on this theme: the President, he wrote, “was once assumed to have been a well-intentioned political innocent, but he emerges from the historical record as a self-consciously oblique political sophisticate with a highly distinctive leadership style.” Though this interpretation gained popularity, the book outraged Arthur Schlesinger, who wrote in his journal on February 12, 1981, that Greenstein was “a nice fellow—but his thesis these days—Eisenhower the Activist President—is a lot of bullshit.”

Despite Schlesinger’s objections, documentation of the efficacy of Eisenhower’s management inaugurated a trend toward a more positive view of his presidency. In Stephen Ambrose’s 1984 book Eisenhower: The President, Ike emerges as a brilliant leader. Ambrose later called him “the American of the twentieth century. Of all the men I’ve studied and written about he is the brightest and the best.”

Unfortunately, this assessment is tainted by scandal. While some Eisenhower scholars questioned Ambrose’s research after the book’s publication, the enormity of his falsifications was not revealed until after his death. Ambrose lied about his relationship to Eisenhower. He claimed that Ike was so impressed with his book on Civil War General Henry Halleck that he called Ambrose out of the blue and asked him to write his biography. Two Ambrose letters contradict this account. On September 10, 1964, the historian wrote to Ike that he was thrilled to be appointed associate editor of the Eisenhower papers and thought “it only fair that you have an opportunity to see some of my writing.” One sample was the Halleck book. On October 15, Ambrose informed the former President that he was editing World War II documents and wanted “to begin a full-scale, scholarly account of your military career.” He was not considering “a complete biography, as I know little about politics and have even less interest in them.”

Ambrose also claimed that he had talked with Ike alone for “hundreds and hundreds of hours” over five years; his footnotes record nine separate interviews. But Ike’s daily logs show that the historian met with the former President only three times, for a total of less than five hours. They never met privately; one of Eisenhower’s aides was always present.

The most damaging charge to result from these phantom sessions concerns the issue Ambrose singled out as the major failure of Eisenhower’s presidency: civil rights. He quotes Ike as saying he regretted “the appointment of that dumb son of a bitch Earl Warren.” He also writes that Eisenhower “personally wished that the Court had upheld Plessy v. Ferguson, and said so on a number of occasions (but only in private).” For the remark on the chief justice, Ambrose cited an undated interview with the former President; for the opinion on Plessy, he did not provide a source. No one has supplied any documentation that confirms either statement. Ambrose declared, also without any documentation, that “Eisenhower had no Negro friends, not even more than one or two acquaintances. . . . He was uncomfortable with . . . Negroes, so much so that he did not want to hear their side.” These assertions, which have no foundation in fact, lead to the expected conclusion: Ike “ignored the Negro community.”

Ambrose’s fabrications received widespread coverage, but little changed. Eisenhower: The President has not been pulled from library shelves, and its publisher, Simon and Schuster, still sells it in print and as an eBook, touting it as an outstanding reference work with “numerous interviews with Eisenhower himself.” Even the Eisenhower Library bookstore sells it.

By the first decade of the 21st century, most authors had rejected the notion of Eisenhower as ineffective. David Nichols, in A Matter of Justice, has shown how Eisenhower advanced the cause of civil rights, and in Eisenhower 1956 how he skillfully managed the Suez crisis. Journalist Jim Newton’s Eisenhower concentrated on how well the President managed the White House, and historian Jean Edward Smith followed with Eisenhower in War and Peace. In this massive, full-length biography, a quarter of which is devoted to the presidency, Smith concludes that next to Franklin D. Roosevelt, Ike “was the most successful President of the twentieth century.”

While the narrative on the Eisenhower presidency has shifted dramatically, from the story of an inept leader to that of a near-great one, most accounts of the actual events during his administration have remained unchanged. (One recent exception was Evan Thomas’s Ike’s Bluff, which describes how the President thought about nuclear weapons from a strategic vantage point and analyzes how Ike combined his generalship and his civilian authority to maintain a fragile peace during the height of the Cold War.) If we no longer see Eisenhower as the golf-playing innocent happily ignoring the nation’s problems, we do not yet have an unclouded picture of how the man actually governed. The mythology still obscures our vision.

President Eisenhower’s organization revolved around the team concept. To Ike, a military professional who became the civilian commander-in-chief, the use of the team approach emerged logically from his West Point experience. The picture that will emerge in this book is of a military man at the top of the pyramid; his subordinates worked in layers below him and provided information. He listened well and assimilated a wide variety of material before arriving at a decision.

Eisenhower took charge of the budgetary, civil rights, legal, defense and diplomatic issues that he thought needed his personal attention. To reach the best solutions to complicated problems, he designated others inside his administration to carry out specific assignments. Secretary Dulles, for instance, provided valuable advice on foreign affairs. Secretary of Defense Charles Wilson managed his department’s sprawling bureaucracy while the President shaped military policy. In economic matters, the President depended on Secretary of the Treasury George Humphrey and other advisers to help formulate fiscal policy. Although Ike admired and respected Attorney General Brownell, the President nevertheless played a major role in the Justice Department’s direction. He valued these individuals but kept them in their place, emphasizing whenever necessary that he was in charge. In many important aspects of his administration, including critical areas where historians have depicted him as passive or disengaged, the initiatives and policies were Eisenhower’s, even when others appeared to be the prime movers.

Depictions of Eisenhower’s connection to Nixon have followed a particularly dark path. The relationship between the two men is variously described as ambivalent, loathsome, or hateful. In the spring of 1960, columnist and commentator Joseph Kraft wrote in an article in Esquire entitled “IKE vs. NIXON” that “it is remarkable that anyone could even suppose a close rapport between the President and Nixon.” The two men’s linkage puzzled Ambrose, who described them as at best ambivalent toward one another. More recently, in his 2011 book American Caesars, British author Nigel Hamilton states: “Eisenhower had never liked or trusted Nixon, nor did he feel confident about Nixon holding the reins of America’s imperial power.” Hamilton claimed that Ike censored Nixon’s speeches, rarely allowed him to enter the Oval Office, and prevented him from participating in “Cabinet and senior government meetings, save as an observer.” These statements do not deviate at all from the mainstream view among historians; none of them are accurate.

A former presidential speechwriter, Emmet John Hughes, in The Ordeal of Power, released in 1963, claimed: “The relationship between Eisenhower and Nixon, at its warmest over the years, could never be described as confident and comradely.” A pre-publication excerpt that appeared in Look magazine in November 1962 alleges that Eisenhower told Hughes before the 1956 Republican national convention that Nixon “was not presidential timber.” Reporters asked the former President to comment, and he denied ever making that statement. No one has acknowledged Ike’s disclaimer, and the derogatory characterization is regularly used to describe the two men’s relationship.

Partisan biographers like Earl Mazo and Bela Kornitzer published sympathetic accounts about Nixon during his vice presidency, and after leaving office, Nixon defended himself in Six Crises. Many authors cast these works aside in favor of less complimentary depictions. The New Republic serialized a book by William Costello, The Facts About Nixon, just before the 1960 presidential election. Costello declared that Nixon had failed to assist GOP candidates in the 1954 elections and that the Vice President was “was widely blamed for the Republican party’s reckless flirtation with the treason issue.” These accusations were without merit. Most Republicans applauded Nixon for aiding the party’s candidates, and they supported him in his efforts to remove subversives from the federal bureaucracy.

Anthony Summers, in his 2000 bestseller The Arrogance of Power, garnered headlines by claiming that Nixon went into psychotherapy sessions with Dr. Arnold Hutschnecker, who, according to Summers, gave the impression that he was a practicing psychiatrist. The New York Times, a decade later, blithely embraced Summers’s allegations in Hutschnecker’s obituary. The newspaper did not mention that the doctor was not a board-certified psychiatrist and never claimed to be one, or that he testified under oath at Senate and House hearings in November 1973 that he had never treated Nixon for psychological or psychiatric reasons. Hutschnecker’s records of his appointments with Nixon reveal that the doctor met with the Vice President for several annual checkups and on a few other occasions for stress-related illness.

Time magazine editors Nancy Gibbs and Michael Duffy, in The Presidents Club, looked at the relationships among the Presidents since Harry Truman. They include chapters on Eisenhower’s association with Truman, Kennedy, and Lyndon Johnson, as well as Nixon’s association with Johnson, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, and George W. Bush. Although Ike spent more time with Nixon than with the other three Presidents combined, there is no chapter on Eisenhower and Nixon. Instead, the authors repeat the misinformation that “Eisenhower . . . never felt much warmth toward his Vice President.” They also state that Ike had Nixon fire cabinet members, even though he never had that authority.

Jeffrey Frank’s 2013 book Ike and Dick magnifies the factual and interpretative errors. Frank is a well-respected journalist and novelist but untrained as a historian, and his book shows evidence of insufficient research. The small number and limited range of written sources cited suggest that he may have spent a month in the Eisenhower and Nixon presidential libraries; each contains millions of documents that would take years to examine properly. In addition, Frank did not cite any of the thousands upon thousands of documents readily available on microfilm, including Eisenhower’s diaries, legislative conferences, and cabinet meetings. On the basis of the tiny sample he cites, Frank advanced the proposition that the President could be cold blooded or worse and that Nixon reacted as well as he could without losing his integrity. The relationship that emerges is that of a son trying to win the affection of a distant, bullying father. Ike’s opinion of Nixon, according to Frank, changed over time “from the mild disdain that he felt for most politicians to hesitant respect.”

Authors have routinely failed to understand that the relationship between the President and Vice President matured over eight years. At first they did not know each other’s strengths and weaknesses. As Nixon became familiar with how Ike governed, he was better able to adapt the President’s ideas to practical proposals and make himself a trusted part of the administration. This evolving relationship is almost completely absent from most accounts. Instead, incorrect information has been repeated for so long that it has been converted into fact.

Earlier authors have relied on three incidents to demonstrate Eisenhower’s low regard for Nixon. The first starts with the 1952 fund crisis; the second is the unsuccessful “dump Nixon” drive spearheaded by White House disarmament adviser Harold Stassen a month before the 1956 Republican convention; the third came on August 24, 1960, when Eisenhower answered a reporter’s question concerning what contribution Nixon made to the administration by saying “If you give me a week, I might think of one.” The comment made front-page headlines.

Written records of the time show clearly that the general did not try to oust Nixon from the 1952 ticket, and the stubborn fact that he was not removed should give pause to those who stress a theme of discord between the two men. This is an example of the incoherence that bits of lingering mythology give to the standard picture of Eisenhower: he is now seen as a strong leader—yet too hapless to influence the selection of his own running mate. In the second case, Ike suggested to Nixon months before the 1956 Republican convention that he take a cabinet post to gain experience managing a large bureaucracy. The President did not demand that Nixon leave the vice presidency but told him to make the decision he thought best. If Ike had wanted a different running mate for his second term, he certainly had the popularity to choose someone else. He did not approve and certainly never championed Stassen’s initiative. Nixon saw a cabinet post as a demotion that would damage his political future, and he chose to run for reelection. Lastly, the accounts of the August 1960 press conference did not mention that the President was leaving the podium because that was his final question. He stated that he would respond the following week; he did not disclose that he was feeling poorly. No press conference was held the next week, and at the one that followed, no reporter asked the President to comment on the Vice President’s value. After Ike made his intemperate remark, he apologized to Nixon. Authors have omitted that fact.

Such regularly repeated anecdotes affirm the unsubstantiated argument that Ike and Nixon were at odds. In reality, the two men worked well together. Ike grew to have great confidence in his Vice President and had Nixon express opinions during crucial meetings and summarize those of others. Nixon depended on the President to provide these opportunities and put forward his best effort to become the versatile utility player on Ike’s team. More than anyone else in the administration, he understood the President’s intentions on many different fronts and became an articulate spokesman for his policies. Because of Nixon’s desire to advance the President’s initiatives and because Eisenhower recognized his Vice President’s talents, Nixon gradually assumed a more diverse set of duties than anyone else in the administration.

The President considered Nixon knowledgeable in political matters. He provided valuable advice regarding interaction between the executive and Congress, and during the two campaigns. Nixon initially tried to curb McCarthy’s excesses, and when McCarthy angered the President by attacking the Army, Nixon assisted in the White House’s quiet but effective campaign against the senator. The Vice President became the administration’s leading spokesman on civil rights. He chaired the President’s Committee on Government Contracts, advancing minority employment and education. He also regularly spoke out for equal rights and helped push the Civil Rights Act of 1957 through the Senate.

While in Congress, Nixon had been a committed internationalist. As Vice President he traveled to Asia, Latin America, Europe, and Africa, became one of Ike’s most trusted forward observers and matured into an expert on world affairs. The President briefed him before he left and debriefed him upon his return. Nixon relayed both his findings and his discussions with Ike to the National Security Council and relevant cabinet members. He learned a great deal in his travels and met many world leaders, with whom he remained in contact. He and Dulles became intimate friends and shared ideas on the diplomatic initiatives.

The President’s heart attack in 1955 has received a great deal of attention. During his recovery that fall and winter, Nixon assumed added responsibilities. Already overworked, he grew weary and suffered from insomnia; physicians prescribed barbiturates to relieve his symptoms. No one knew how incapacitated both the President and the Vice President were during this period.

Even in this troubling situation, Ike and Nixon worked well together. The Vice President’s two military advisers were among the many who refuted the allegations of discord between the leaders. Robert Cushman, who handled national security matters for the Vice President, recalled that he never heard Nixon say anything critical of the President. Nixon’s appointment secretary, Donald Hughes, reported that no animosity existed between the leaders.

Three months after leaving office, Nixon commented in a letter to a constituent, Mrs. Barbara Berghoefer, that while he did not know how history would view Ike, “for devotion to duty, for unshakeable dedication to high moral principle, for a determination always to serve what he regarded as the best interests of all Americans—on each of these scores, Mr. Eisenhower ranks with the greatest leaders our nation has ever had.” He was privileged to have worked with Ike and to have learned “that real leadership is not a matter of florid words or action for its own sake. It is, rather, the undeviating application of the basic principles to the shifting details of day-to-day problems.”

Sitting in the Oval Office on July 21, 1971, more than two years after Eisenhower’s death, President Nixon reflected on his role in that earlier administration. He believed he had made a substantial contribution to solving a wide range of problems. During the second term, he recalled, the President had him substitute for him at cabinet and NSC meetings as well as participate in many critical decisions. Ike, Nixon concluded, had treated him “extremely well.” Due to lingering partisan bitterness and the Watergate scandal, Nixon remains an easy target. The fable that Ike limited Nixon’s role in the administration and that the two were antagonistic toward each other has permitted the selective rehabilitation of Ike’s reputation without requiring a similar reexamination of Nixon’s, and this selectivity blocks an accurate understanding of the Eisenhower presidency. The enormous weight of the evidence points to a fundamentally different relationship. Ike entered the presidency ready to lead. Nixon was eager to follow.

Irwin F. Gellman has taught at several American universities and is now an independent scholar living in the Philadelphia suburbs. His books include The Contender, an account of Richard Nixon’s congressional years; Secret Affairs, which explores the relationship between Franklin Roosevelt, Cordell Hull, and Sumner Welles; and Good Neighbor Diplomacy and Roosevelt and Batista, which look at U.S. policy in Latin American and Cuba from 1933 to 1945.

Note on Sources

The collections in the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas, contain historical records and papers relating to President Eisenhower and his associates. For this work, the author consulted a letter from Virginia and Holmes Tuttle to Eisenhower re the Morison book, May 4, 1965, B 5, F GI- 2T, 1965 Principle File, Post-Presidential Papers; Stephen Ambrose to Eisenhower, September 10 and October 15, 1964, B 24, F Am(1), Principle File, Post-Presidential Papers; Meeting notes, April 17, 1956, B 2, F legislative meetings 1956 (2), Legislative Meeting Series; Eisenhower to Gross, April 27, 1963, B 4, F “Hu,” Post-Presidential Papers; and the Robert Cushman oral history.

The Richard Nixon Library in Yorba Linda, California, contains Nixon’s letter to Barbara Berghoefer, April 21, 1961, B 237, Eisenhower 1/2, Series 320, and the Oval Office tape for July 21, 1971, conv. no. 541-2.

In addition to the works cited within the text, published sources include Dean Albertson ed., Eisenhower as President (New York: Hill and Wang, 1963); Stephen E. Ambrose, Eisenhower, vol. 1: Soldier, General of the Army, President-Elect, 1890–1952, vol. 2: The President (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1983–1984), and To America: Personal Reflections of an Historian (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002); James David Barber, The Presidential Character: Predicting Performance in the White House (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1972); Taylor Branch, Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954–63 (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988); Herbert Brownell, Advising Ike: The Memoirs of Attorney General Herbert Brownell (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1993); William H. Chafe and Harvard Sitkoff, eds., History of Our Time: Readings on Postwar America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983); William Costello, The Facts About Nixon: An Unauthorized Biography (New York: Viking Press, 1960); Norman A. Graebner, The New Isolationism (New York: Ronald Press Co., 1956); Neil Jumonville, Henry Steele Commager: Midcentury Liberalism and the History of the Present (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999); Murray Kempton, “The Underestimation of Eisenhower,” Esquire 68 (September 1967); Bela Kornitzer, Real Nixon: An Intimate Biography (New York: Rand McNally, 1960); John Malsberger, “Dwight Eisenhower, Richard Nixon, and the Fund Crisis of 1952,” The Historian 73 (Fall 2011); Earl Mazo, Richard Nixon: A Political and Personal Portrait (New York: Harper, 1959); Richard E. Neustadt, Presidential Power: The Politics of Leadership (New York: Wiley, 1960); Richard Rayner, “Channelling Ike,” The New Yorker (April 26, 2010); James Reston, Sketches in the Sand (New York: Knopf, 1967); Thomas E. Ricks, The Generals: American Military Command From World War II to Today (New York: Penguin Press, 2012); Richard Rovere, Final Reports: Personal Reflections on Politics and History in Our Time (New York: Doubleday, 1984); Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., “Ike Age Revisited,” Reviews in American History 11 (March 1983); and Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., Journals, 1952–2000, ed. Andrew Schlesinger and Stephen Schlesinger (New York: Penguin Press, 2007).

PDF files require the free Adobe Reader.

More information on Adobe Acrobat PDF files is available on our Accessibility page.