Eisenhower and McCarthy

How the President Toppled a Reckless Senator

Fall 2015, Vol. 47, No. 3

By David A. Nichols

© 2015 by David A. Nichols

A generation ago, William Bragg Ewald, Jr., wrote a book, Who Killed Joe McCarthy?—a title worthy of an Agatha Christie whodunit. That question has reverberated for six decades.

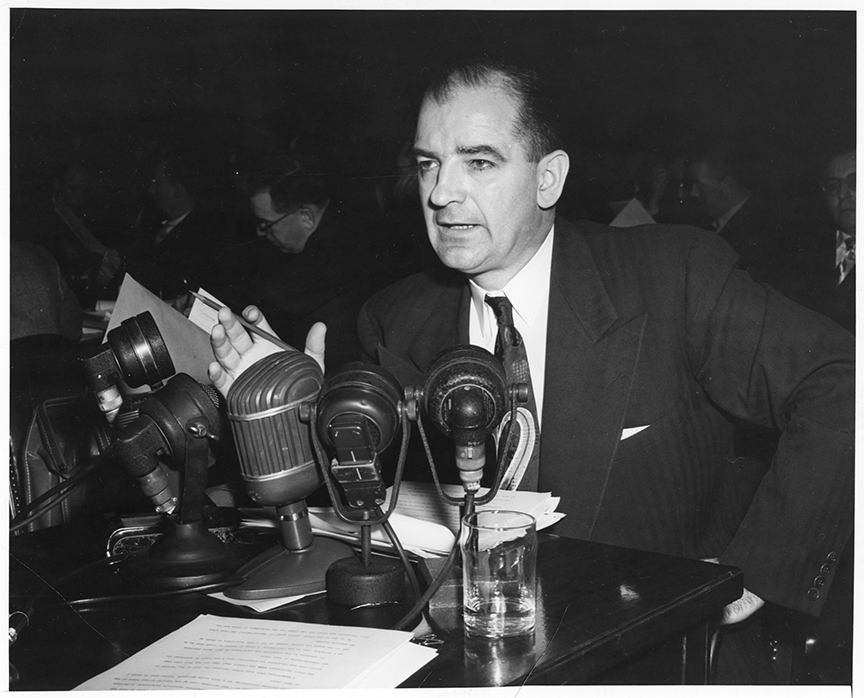

Beginning in 1950, Wisconsin’s junior U.S. senator, Joseph R. McCarthy, threw the nation’s capital into turmoil with his reckless, unsubstantiated charges. In a campaign to rid America of an alleged communist conspiracy, the senator charged respected citizens, especially government employees, with being Soviet agents. McCarthy’s lack of respect for the truth, his insatiable appetite for headlines, and his willingness to damage reputations turned “McCarthyism” into an enduring epitaph in our political language.

Yet, by mid-1954, McCarthy’s political influence had been essentially destroyed. How did that happen?

The answer is Dwight D. Eisenhower.

“Ike is Don Corleone, the godfather,” says Daun van Ee, an editor of the Eisenhower published papers. “He knows how to take somebody out without leaving any fingerprints.”

The standard explanations for McCarthy’s political demise are well known. Joe, an alcoholic, supposedly did himself in. He was damaged by Edward R. Murrow’s legendary See It Now television program. His reputation was tarnished by the Army-McCarthy hearings, by the unsympathetic glare of the television cameras, and by his confrontation with the wily Joseph Welch (the attorney the White House recruited to represent the Army).

In the traditional story, the final nail in McCarthy’s political coffin was the censure vote by the United States Senate on December 2, 1954.

An “Eyes Only” File Sheds Light on Eisenhower and McCarthy

In recent years, pro-McCarthy authors have attempted to repair the senator’s reputation by arguing his political enemies destroyed him in order to cover up Soviet espionage in the United States government. However, Eisenhower cannot be justifiably charged with such negligence. Eisenhower took the possibility of subversion seriously, but firmly believed his methods would be effective whereas McCarthy’s demagogic tactics would fail.

William Ewald was the first to tap an immense cache of documents reflecting the conflict with McCarthy that Fred Seaton, assistant secretary of defense, collected on President Eisenhower’s orders during the Army-McCarthy hearings. Seaton impounded thousands of pages of letters, telephone transcripts, memoranda, and documents. He locked them up, took them with him when he became secretary of the interior, and—when he left the government—hauled them home to Nebraska.

Ewald, who later worked for Seaton at the Interior Department, recalled the secretary pointing to a locked file and saying: “I’ll never open that until you-know-who tells me to.” When Seaton died, his “Eyes Only” file was donated to the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas.

Those papers, along with other declassified documents, paint a tale of strategic deception, a realm in which Dwight Eisenhower was expert. In 1944, with the help of allies, the general had successfully hoodwinked the German leadership about when and where the largest military expeditionary force in human history would land in Europe. “Operation Fortitude” involved fake armies, dummy landing craft and air fields, fraudulent radio transmissions, and misleading leaks through diplomatic channels and double agents.

Eisenhower understood that carefully planned, rigorously implemented deception can confuse an enemy until he makes a mistake; then he can be ambushed. That, politically, is what Eisenhower did to Joe McCarthy. Only a half dozen trusted aides knew what was happening. Others—including most of the era’s great reporters—missed the real story.

Ike Helps Create Myth of Himself as Disengaged and Grandfather

Much of the residual difficulty lies in the enduring myth about Eisenhower’s leadership— that he was a disengaged, grandfatherly President more interested in playing golf than in the effective exercise of leadership. That legend—discredited by a growing body of research the past three decades—was perpetuated initially by politically biased historians who never forgave the general for denying the presidency to Adlai Stevenson in 1952.

In part, Eisenhower was the author of his own myth. He was obsessive about protecting the Oval Office from controversy. In particular, critics grumble that Eisenhower was cowardly in his response to McCarthy, refusing to “speak out” about the red-baiting senator’s excesses.

In 1954, columnist Joseph Alsop, after listening to Eisenhower’s restrained news conference statement targeting McCarthy’s methods (without mentioning his name), sneered to a colleague, “Why, the yellow son of a bitch!”

Contributing to this theory was Eisenhower’s response during the 1952 campaign to McCarthy’s attack on Gen. George C. Marshall, Army chief of staff during World War II. Marshall, more than anyone, was responsible for Eisenhower’s swift ascent in the Army, leaping over dozens of generals to become supreme allied commander in Europe, the architect of D-day, and the hero of the drive to defeat the Nazis.

In the 1952 presidential campaign, Eisenhower had included in a speech prepared for delivery in Wisconsin a paragraph defending Marshall, hoping to deliver it with McCarthy on stage. However, Eisenhower, an inexperienced politician, was pressured that afternoon by Wisconsin Republican leaders (not McCarthy) to delete the 74 words of praise because they feared losing Wisconsin’s electoral votes.

Unfortunately, campaign press aide Fred Seaton had already hinted to New York Times reporter William Lawrence that there would be praise for Marshall in the speech. Joe McCarthy misled Lawrence about how the deletion took place. The press made much of the candidate’s decision to omit his defense of Marshall. However, in an August 22 news conference, Eisenhower had already defended Marshall as “a perfect example of patriotism.”

Ike “Ignores” McCarthy; “This he cannot stand”

There is a shred of truth in the allegation. Eisenhower did not believe presidential rhetoric would take down McCarthy, and he was right about that.

Recent research shows that presidential oratory rarely results in historic change; that happens when Presidents exploit a crisis to exercise transformative leadership. Consider Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War or Franklin Roosevelt and the Great Depression. However, modern pundits persist in rating Presidents by their use of the “bully pulpit.” Eisenhower understood demagogues like McCarthy. In April 1953, he wrote in his diary: “Nothing will be so effective in combating his particular kind of trouble-making as to ignore him. This he cannot stand.” Eisenhower refused to use the senator’s name in public. His repudiation of pleas to denounce McCarthy perplexed friends and supporters. Ike’s persistent response was that “getting in the gutter” with the senator would only elevate McCarthy’s status. Years later, Robert Donovan, a supportive journalist, clung to the belief that Eisenhower could have destroyed McCarthy if he had delivered “one great speech on the immorality and illegality of McCarthyism.” Eisenhower knew better; such rhetoric would only play to the senator’s strengths.

GOP Takes Congress as Ike Wins; McCarthy Gets a New Weapon

Ironically, in 1953, due to Eisenhower’s election, McCarthy acquired a new platform for his crusade. The Republican onevote majority in the Senate resulted in McCarthy’s appointment as chair of the Government Operations Committee and its permanent investigative subcommittee. In the latter capacity, the senator subpoenaed witnesses, conducted one-senator hearings, accused witnesses of guilt-by-association, and labeled as “obviously communist” any one who dared to invoke constitutional protections against self-incrimination.

In 1953, Eisenhower had priorities that took precedence over dealing with Joe McCarthy. The nation was still at war in Korea, and recovering from the traumas of depression and World War II.

The Cold War with the Soviet Union sustained a climate of fear that was the lifeblood of McCarthyism, including the fear of subversion. Given Eisenhower’s priorities, revolving around his commitment to “waging peace” (a favorite phrase), virtually everything McCarthy said or did was diametrically opposed to the agenda of his party’s new President.

Eisenhower’s achievements abroad during 1953–1954 were historic. He ended the Korean War, prosecuted the Cold War on multiple fronts, offered “a chance for peace” to the new Soviet leadership after Josef Stalin died, crafted a “new look” defense policy rooted in nuclear deterrence, and delivered a historic “Atoms for Peace” proposal at the United Nations.

In 1954, when the French were routed at Dien Bien Phu, Eisenhower rejected French pleas to intervene, risking the possibility that McCarthy might accuse him of “losing Indochina.”

At home, the President skillfully managed his narrow majorities in the Congress. Eisenhower pioneered advances in civil rights—desegregating the District of Columbia, completing desegregation of the military, and appointing Earl Warren to the Supreme Court.

In 1953, he put together a sweeping legislative program that preserved and enhanced New Deal programs and submitted it to Congress in January 1954. He also made controversial decisions to permit the executions of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg for spying and to accept the Atomic Energy Commission’s denial of security clearance to scientist Robert Oppenheimer, the “father of the atom bomb.”

McCarthy Uses Committee to Investigate “Ike’s Army”

Eisenhower refused to permit McCarthy to distract him from these priorities.

Still, he was not as passive in 1953 as historians have assumed. Like the military commander he was, Ike acted strategically. He instituted an internal security program designed to both steal McCarthy’s thunder and root out genuine security risks.

He crushed McCarthy’s attempt to derail Charles Bohlen’s nomination as ambassador to the Soviet Union, denounced McCarthy inspired book burnings in America’s overseas libraries, and effectively countered McCarthy when the senator called for a blockade of allied ships delivering goods to China.

Complaints that Eisenhower took too long to act against McCarthy are misguided. Eisenhower was a master of timing, as the D-day invasion demonstrated. If the President had tried to destroy McCarthy in 1953, he probably would have failed. One must select the right time, as well as the most effective method, to take on an enemy.

Former President Harry S. Truman openly denounced McCarthy for three years, but his rhetorical attacks only enhanced the senator’s prestige; Ike ruined him in less than half that time.

Then, on August 31, 1953, McCarthy launched hearings into communist infiltration into the United States Army—Ike’s Army. While Eisenhower did not respond in public, it was only a matter of time. Joe McCarthy had signed his own political death warrant by assaulting the service to which the general had devoted his adult life.

The Turning Point in 1954: A Scandal Involving McCarthy

By January 1954, Joe McCarthy’s prestige was at its zenith; 50 percent of Gallup Poll respondents approved of the senator, with 29 percent unfavorable. Eisenhower had concluded that McCarthy was more than a nuisance; he was a threat to the country’s stability, to the President’s foreign policy goals, to his legislative program, and to his party’s and his own electoral prospects.

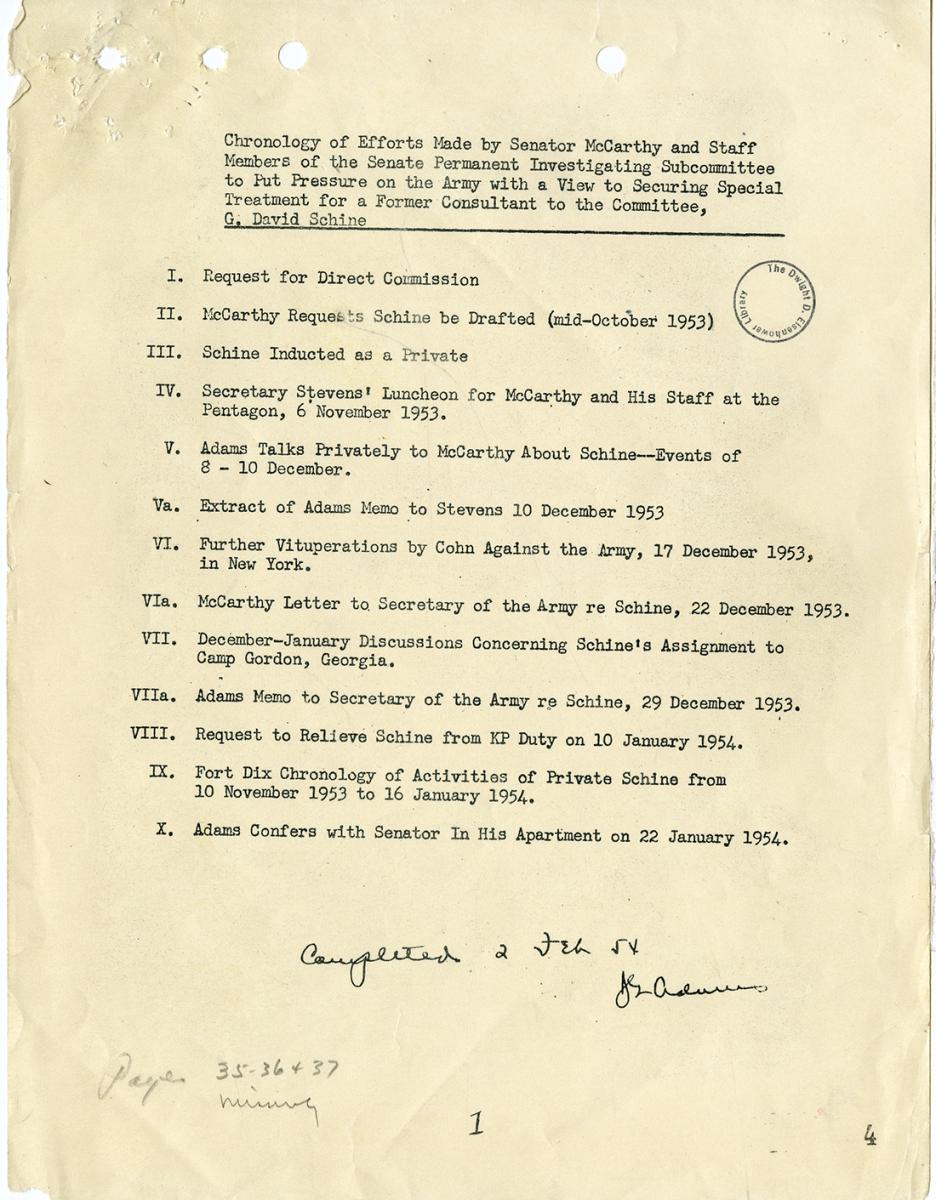

In January 1954, Eisenhower did something breathtaking and dangerous; he launched a clandestine operation designed to wrap a scandal around the neck of a prestigious United States senator in the President’s own party in an election year. The controversy involved McCarthy’s chief counsel, Roy Cohn, and his frantic attempts to keep Pvt. G. David Schine with him on the subcommittee. Schine had been an unpaid consultant to the subcommittee until he was drafted into the Army. These men were, in the words of Attorney General Herbert Brownell, “inseparable.”

Cohn’s rage over his inability to obtain a special commission for Schine apparently pushed McCarthy into investigating the Army. The attorney’s efforts to secure special privileges for Schine, often involving the senator, was what the Army-McCarthy hearings in mid-1954 were ostensibly about.

Eisenhower carried off his anti-McCarthy operation by means of rigorous delegation to a handful of trusted subordinates; these included Chief of Staff Sherman Adams; Vice President Richard Nixon; Press Secretary James Hagerty; Attorney General Herbert Brownell, Jr., and his deputy, William Rogers; Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., the administration’s representative to the United Nations; and Assistant Secretary of Defense Fred A. Seaton, who collaborated with H. Struve Hensel, the Pentagon’s general counsel. While less intimate with the President, Secretary of the Army Robert Stevens and Army counsel John G. Adams played critical roles. These men were expected, like foot soldiers in war, to put their lives and reputations on the line to protect the President and extinguish the political influence of Joe McCarthy.

Strong Response to Cohn’s Threat to “Wreck the Army”

On January 21, 1954, at a meeting in Attorney General Brownell’s office, Eisenhower’s chief advisers learned the shocking details about Roy Cohn’s threats to “wreck the Army” to keep Private Schine with him and McCarthy’s subcommittee.

Eisenhower, although not in attendance, now had potent ammunition to use against McCarthy. Sherman Adams ordered John G. Adams, the Army counsel, to write up a report summarizing Cohn’s harassment of the Army. Lodge later called this meeting Eisenhower’s “first move” against McCarthy.

McCarthy further antagonized Eisenhower when, in a February 18 hearing, the senator charged that Gen. Ralph Zwicker, a hero in the war in Europe and then commandant at Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, was “not fit to wear the uniform” of the United States Army.

On February 24, unknown to Eisenhower, Army Secretary Stevens attempted to secure a pledge from McCarthy that Army officers would not be further abused. Stevens met secretly with McCarthy and the other Republican senators on the subcommittee at the so-called “chicken lunch”; the senators talked Stevens into signing an agreement that the newspapers immediately branded a “surrender” to McCarthy.

That day, Eisenhower returned home from golfing in California. He was dismayed to learn that commentators mistakenly assumed the President had ordered Stevens to capitulate. The next day, a furious Eisenhower convened key staff members, including Stevens, at the White House and personally oversaw the writing of a statement repudiating the “surrender” document.

From that moment on, preparations intensified in the Pentagon for the release of the “Schine report.” Assistant Secretary Seaton, with the assistance of Defense Department general counsel Hensel, was editing the document for publication.

On February 23, Lodge wrote Eisenhower about Maj. Irving Peress, a Camp Kilmer dentist McCarthy had accused of being a communist. Lodge suggested their antiMcCarthy operation might gain momentum with help from “a friendly senator” and “a little luck.” On March 9, 1954, the administration got both. Sherman Adams’s good friend, Vermont’s Republican Senator Ralph W. Flanders, ridiculed McCarthy in a speech on the Senate floor. Flanders words dripped with sarcasm: “He dons his war paint. He goes into his war dance. He emits his war whoops. He goes forth to battle and proudly returns with the scalp of a pink Army dentist.”

That night, Edward R. Murrow’s See It Now television program quoted Flanders as part of an eloquent condemnation of the senator.

Report on Schine Released; Senate Censures McCarthy

Those events set the stage for March 11, 1954.

That day, on Eisenhower’s secret orders, Seaton released a 34-page, carefully edited account of the privileges sought for David Schine to key senators, representatives, and the press. The document ignited such a firestorm of negative publicity that, on March 16, the McCarthy subcommittee agreed to hold televised hearings. McCarthy would temporarily step down as chair, to be replaced by South Dakota Senator Karl Mundt.

The hearings began April 22 and continued until June 17. McCarthy’s reputation had already been damaged prior to the hearings; the senator’s abusive demeanor on television repulsed viewers, and the Army’s attorney, Joe Welch, cleverly exposed McCarthy’s duplicity. On June 9, Welch climaxed his baiting of McCarthy, exclaiming:

“Have you left no sense of decency?”

Once the hearings ended, there was a movement for censure that reached fruition on December 2, 1954, by a vote of 67 to 22; all of the negative votes were cast by Republicans.

There can no longer be any doubt that Dwight Eisenhower and his trusted subordinates engineered this devastating assault on McCarthy. Following condemnation by his colleagues, McCarthy was still around, but his influence was a shell of what it had been.

In a June 1955 meeting of Republican congressional leaders, Eisenhower repeated a saying that was making the rounds in Washington; “It’s no longer McCarthyism,” the President said. “It’s McCarthywasm.”

On May 2, 1957, Senator Joseph R. McCarthy died; he was 48 years of age.

David A. Nichols is former vice president for academic affairs and dean of faculty at Southwestern College in Kansas. This article is a preview of his forthcoming book on Eisenhower and Joseph McCarthy, to be published by Simon & Schuster in 2016. Nichols holds a doctorate from the College of William and Mary. He is the author of A Matter of Justice: Eisenhower and the Beginning of the Civil Rights Revolution and Eisenhower 1956: The President’s Year of Crisis—Suez and the Brink of War (Simon & Schuster, 2007, 2011). Nichols is also the author of Lincoln and the Indians: Civil War Policy and Politics (first published in 1978 by the University of Missouri Press and republished by the Minnesota Historical Society in 2012).

Note on Sources

This article is extracted, with permission from Simon and Schuster, from the full-length volume to be published in 2016, and it is not possible to cite all of the key sources here. The massive Fred A. Seaton “Eyes Only” collection at the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library is critical, and the other resources at that library have been thoroughly investigated. The Eisenhower published papers (Louis Galambos and Daun van Ee, eds., The Papers of Dwight David Eisenhower [Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984–2001]) are drawn from materials at the Eisenhower Library and always an important source. So too are the memoirs and oral histories from the period, especially Sherman Adams, First-Hand Report: The Inside Story of the Eisenhower Administration (London: Hutchinson, 1961) and John G. Adams, Without Precedent: The Story of the Death of McCarthyism (New York: Norton, 1983). William Ewald’s book, Who Killed Joe McCarthy (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1984) is thoroughly researched but also based on his personal experiences as a White House staff member and collaborator on the former President’s memoirs. There are numerous studies of the McCarthy side of the story, but the two most frequently cited are Thomas C. Reeves, The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy (New York: Stein & Day, 1982) and David M. Oshinsky, A Conspiracy So Immense: The World of Joe McCarthy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983, 2005).