Eisenhower, the Frontier, and the New Deal

Fall 2015, Vol. 47, No. 3

By Timothy Rives

This year marks the 125th anniversary of both the birth of Dwight D. Eisenhower and the U.S. Census Bureau’s declaration that the American frontier had closed.

The events are related, for Eisenhower’s understanding of the frontier’s demise shaped his ideas on the proper role of government and, as a result, led him to affirm New Deal social welfare programs.

The primary evidence for this claim is found in letters at the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library between Eisenhower, former General of the Army and 34th President of the United States, and a military comrade named Bradford G. Chynoweth. Ike and Chyn, as the men were known to friends, met in Panama in the early 1920s during one of the most formative periods in Eisenhower’s life. His assignment as executive officer of the 20th Infantry Brigade under Gen. Fox Conner—a leading Army thinker— would be “a sort of graduate school in military affairs and the humanities,” Eisenhower wrote in his memoir At Ease.

Ike’s boyhood love of history, which had slackened under the rote memorization of West Point instruction, revived under Conner’s tutelage as he worked his way through classics of history and philosophy, debating the finer points over long trail rides and around campfires with Conner and fellow officers like Chynoweth.

Ike left Panama in 1924 with a new zeal for his profession. In relatively brisk order, he would march through a series of Army schools and brilliant assignments with the assistant secretary of war and the Army chief of staff, climaxing some years later as the Supreme Commander, Allied Expeditionary Force in the Second World War.

In short, scholars note, the Fox Conner “school” helped put Eisenhower on his historic trajectory to the White House.

Ike, Chyn Exchange Letters, Debate Issues

A 1954 letter from Chynoweth early in Ike’s first presidential term offered a chance to relive “the very fine and heated debates” he had shared with Chyn in Panama some 30 years earlier.

Brig. Gen. Bradford G. Chynoweth was a brilliant, if acerbic, man who spent most of the Second World War in a Japanese prisoner of war camp. Chyn left the Army after the war to pursue studies at the University of California, Berkeley, where classroom encounters with liberal professors honed his self-described “radical Republican” beliefs.

Now he aimed these beliefs at his old friend, the President. He deviated from Eisenhower’s moderate, “middle of the road” policies, he said, but still wanted to express his “great admiration for your ability to stand up to pressures that would crush many men.

“Courage is three-fourths of the battle, and you have it,” he told Ike.

Ike acknowledged Chyn’s note with a short one of his own, but on second thought decided to rekindle their Panamanian conversations with a much longer rejoinder— a full-fledged defense of his moderate political philosophy.

Eisenhower had promoted the “Middle Way,” as he characterized his ideas on government, from the late 1940s, when he made his first public comments on the role of the state, until the end of his life in 1969. (His last article for Reader’s Digest magazine, published the month following his death, was on the Middle Way.)

Eisenhower’s Middle Way speeches and articles consistently promoted a bright centrist line between concentrations of unbridled private power on one side of the road and unlimited state power on the other. Eisenhower viewed the march of American history as a struggle to stay the middle course. His political heroes Abraham Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt were men of the middle, Ike liked to say, pointing to Lincoln’s Homestead Act and Roosevelt’s corporate “trust-busting” as examples.

Ike Sees Two Sides In the Constitution

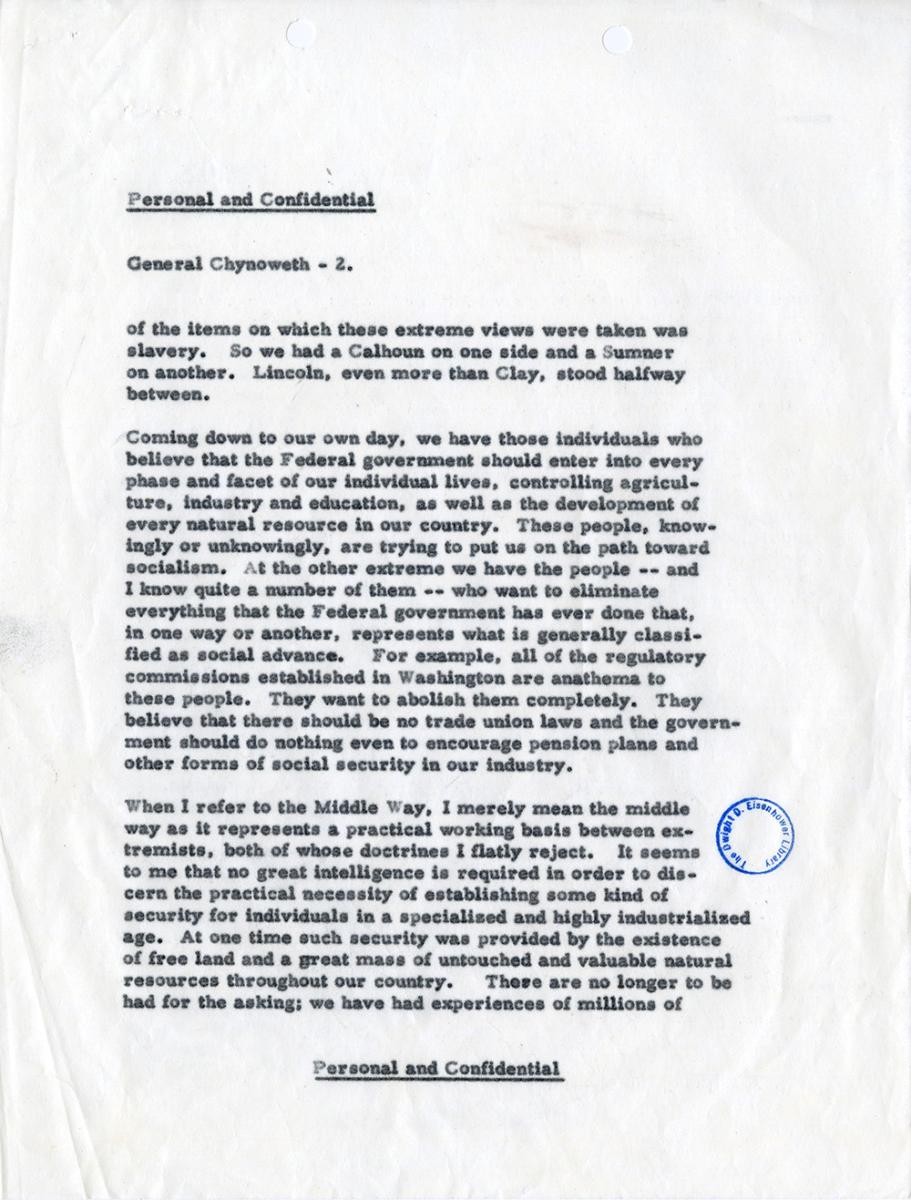

To Chynoweth, Ike explained how the Constitution was “nothing else so much as an effort to find a middle way between the political extremists of that particular time. On the one side were the individualists—the fanatical believers in a degree of personal freedom that amounted almost to nihilism. . . . At the other extreme were the great believers in centralized government—those who mistrusted the decisions reached by popular majorities.”

Ike noted the same split in contemporary politics. There were those who wanted the federal government to “control every phase of our individual lives” versus those who wanted to “eliminate everything that the Federal government has ever done that . . . represents what is generally classified as social advance.”

Eisenhower’s plan to expand Social Security by 10.5 million workers in 1954 was wending its way through Congress that summer. The issue was probably the impetus for Chynoweth’s initial spiny missive to his friend. Ike sensed this and moved to its defense.

“It seems to me,” Eisenhower said, “that no great intelligence is required in order to discern the practical necessity of establishing some kind of security for individuals in a specialized and highly industrialized age. At one time such security was provided by the existence of free land and a great mass of untouched and valuable natural resources. These are no longer to be had for the asking.”

Ike’s letters to Chynoweth repeat arguments he made elsewhere in defense of the Middle Way. But this reference to the loss of “free land” and “natural resources” was something new, and it reveals the Middle Way’s intellectual debt to a strain of political thought not commonly associated with Eisenhower.

Frederick Jackson Turner Inspires Progressive Ideas

Understanding how Ike made the connection between the extinction of the frontier and the necessity for federal welfare programs requires a look back to, of all places, the 1893 World’s Fair.

The Census Bureau’s 1890 pronouncement of the frontier’s extinction had gathered little notice outside of specialist circles until a young Wisconsin historian named Frederick Jackson Turner presented his interpretation of the closure at a meeting of the American Historical Association (AHA) in July 1893. The AHA met that year at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago for a “World’s Congress of Historians and Historical Students,” a nod to high culture by event organizers who wanted to present visitors with something more than cheap amusements and confections.

An eclectic scholarly program offering the public a range of talks from “English Popular Uprisings in the Middle Ages” to “Early Lead Mining in Illinois and Wisconsin” preceded Turner’s own lecture on the “Significance of the Frontier in American History.”

Although conference observers reported little of Turner’s talk in their reviews at the time, his “frontier thesis” would dominate the interpretation of American history for more than a generation and remains a matter of academic debate to this day.

Turner’s “frontier thesis,” simply stated, concluded: “The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward, explain American development.” The frontier—not memes of primitive European social organization—accounted for a distinctive American polity, both democratically egalitarian and ruggedly individualistic, according to Turner.

Free land was the “most significant thing” about the frontier, Turner claimed. “So long as free land exists, the opportunity for a competency [that is, a livelihood] exists, and economic power secures political power.” To Turner, the closing of the frontier meant much more than merely the end of a major chapter in American history; the loss of free land meant that economic security and political freedoms must be built on a new foundation.

The new foundation that Turner and his “Progressive” interpreters would identify over the coming years was the state. “Progressivism,” an umbrella term for the wide-ranging reform efforts at work in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was an attempt to mitigate the disruptive changes wrought by industrialization, urbanization, and immigration through government action.

The closing of the frontier provided further proof to the Progressives that the state must respond in novel ways to the complexities of a new age.

Turner’s Ideas Influence Two Future Presidents

Addressing the AHA again in 1910, Turner reported:

"[T]he present finds itself engaged in the task of readjusting its old ideals to new conditions and is turning increasingly to government to preserve its traditional democracy. It is not surprising that socialism shows noteworthy gains as elections continue; that parties are forming on new lines; that the demand for primary elections, for popular choice of senators, initiative, referendum, and recall is spreading, and that the regions once the center of pioneer democracy exhibit these tendencies in the most marked degree. They are efforts to find substitutes for that former safeguard of democracy, the disappearing free lands. They are the sequence to the extinction of the frontier."

An important corollary to the Turner thesis was the belief that the free land of the frontier had provided a “safety valve” of economic relief to eastern factory workers thrown from their jobs by recession or depression. The safety valve must also be recreated by the state in the form of direct government relief to those unemployed by the dislocations of an industrialized economy.

From its somewhat drowsy academic start in Chicago, the “frontier thesis” advanced steadily into the new century. The thesis won wide circulation by a combination of academic and popular promotion by Turner in seminars to graduate students, encyclopedia entries, teacher resource guides, and essays in popular magazines such as the Atlantic Monthly.

Turner, a gifted orator, also proselytized fellow historians and the general public with an ambitious lecture schedule. Influential academic friends such as future President Woodrow Wilson, Turner’s former fellow graduate student at the Johns Hopkins University, also eagerly helped spread his ideas beyond the efforts of other scholars with frontier theories of their own.

Turner’s “frontier thesis” was so widely known by the 1930s that the first published bibliography of its influence amassed 125 entries; by 1985 the bibliography had grown to nearly 250 pages of citations. Turner’s fame grew so great, his thesis became so prevalent, that like the works of Sigmund Freud, the “Significance of the Frontier in American History” wasn’t read so much as it was inhaled at cocktail parties. Ideas about the frontier’s extinction were in the air, and nowhere was that air thicker than among the early New Dealers.

Most importantly, one of them was Turner’s former Harvard student, Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Turner’s presence is clear in Roosevelt’s most important speech of the 1932 campaign: the September 23 address on “Progressive Government” to the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco. With the country deep in its Great Depression, Roosevelt laid out his understanding of the nation’s predicament, its cause, and its solution.

“A glance at the situation today only too clearly indicates the equality of opportunity as we have known it no longer exists,” Roosevelt said. “Our industrial plant is built. . . . Our last frontier has long since been reached, and there is practically no more free land. There is no safety valve in the form of a Western prairie to which those thrown out of work by the Eastern economic machines can go for a fresh start.

“Our task now,” he averred, “is not discovery or exploitation of natural resources, or necessarily producing more goods. It is the soberer, less dramatic business of administering resources and plants already in hand, of seeking to reestablish foreign markets for our surplus production, of adjusting production to consumption, of distributing wealth and products more equitably, of adapting existing economic organizations to the service of the people. The day of enlightened administration has come.”

The “enlightened administration” demanded for these post-frontier times, according to Roosevelt, would be the New Deal, an amalgam of reforms and programs that would transform the relationship between the citizen and the state; and the state and the economy. Social Security, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the Tennessee Valley Authority are among its many living legacies.

The New Deal’s NRA: Substitute for Frontier

The National Recovery Administration (NRA), however, was the New Deal’s most ambitious attempt at post-frontier “enlightened administration.” The NRA was established to revitalize industry and trade, grow employment, and improve labor conditions through codes of fair competition to govern industries and trades, and through the President’s reemployment agreement, a general code for voluntary compliance until specific industry and trade codes could be approved. Or in NRA Director Hugh S. Johnson’s plainer words, the NRA was “a safety valve like our vanished frontiers.”

Conservatives, predominately Republicans, saw nothing of the sort in the NRA or in most New Deal programs. President Herbert Hoover attacked Roosevelt’s Commonwealth Club speech during the 1932 campaign as “a philosophy of stagnation and despair.” Once out of office he continued the battle throughout the 1930s, his criticism broadly representative of the conservative reaction to the New Dealer arguments.

In sum, Hoover and his fellow conservatives believed the New Deal concept of the “frontier” was too small. New worlds were yet to be conquered.

“There are vast continents awaiting us of thought, of research, of discovery, of industry, of human relations, potentially more prolific of human comfort and happiness than even the ‘Boundless West,’” Hoover wrote in The Challenge to Liberty in 1934. “But they can be conquered and applied to human service only by sustaining free men, free in spirit, free to enterprise, for such men alone discover the new continents of science and social thought and push back their frontiers. Free men pioneer and achieve in these regions; regimented men under bureaucratic dictation march listlessly, without confidence and hope,” he said.

Ike, Now President, Renews Discussions with Chynoweth

Such was the argument picked up 20 years later by Eisenhower’s old Panama friend Bradford Chynoweth when he replied to the President’s equivalence of free land with security.

“True, Ike, the frontier closed the very year you and I were born. But free land was never security,” he said. Pioneers had to “earn their free land! That wasn’t security,” Chyn exclaimed. “That was radical industry.”

Channeling Hoover, Chyn continued, “The frontiers of life are infinite. . . . We will never reach and exploit the new frontiers if we throttle industry, and put a strait jacket on the pioneer types.”

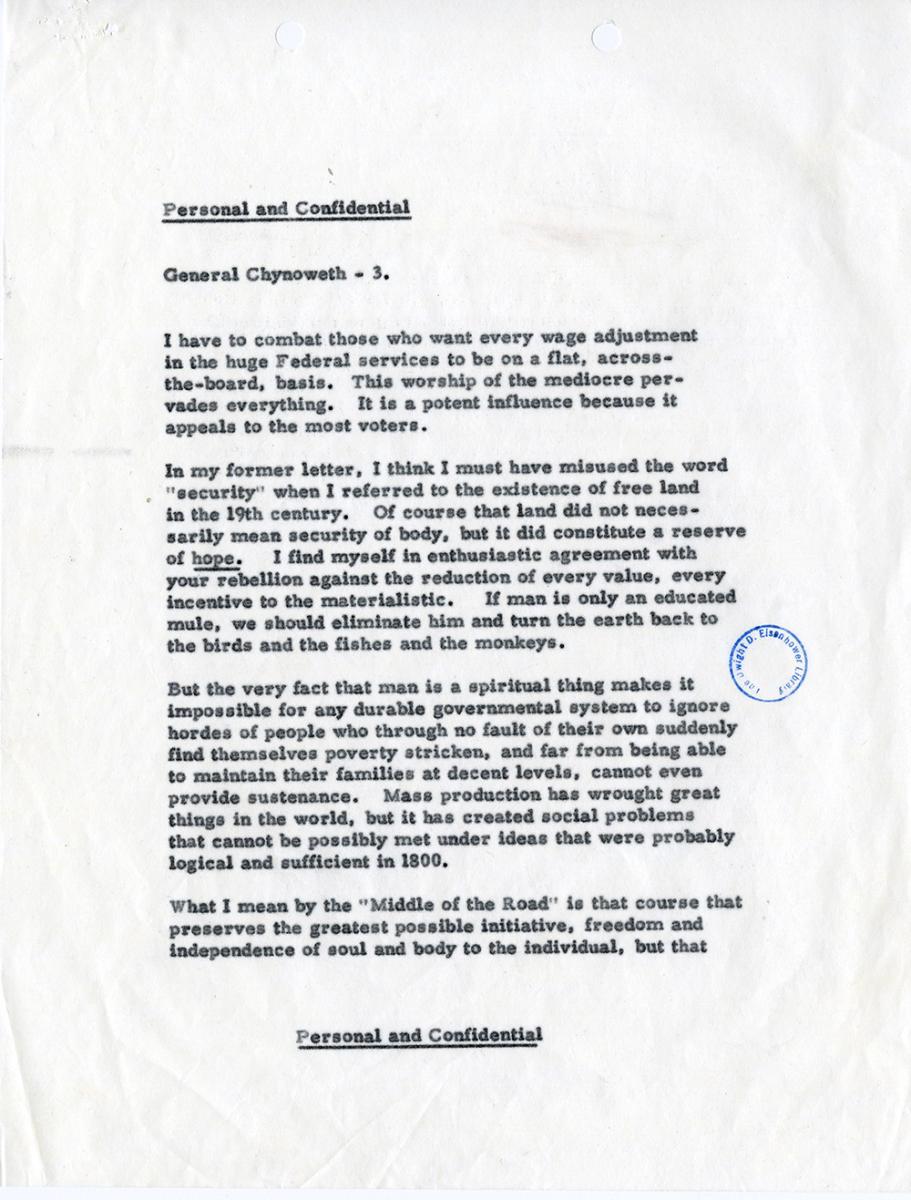

Ike admitted he might have misused the word “security” when he “referred to the existence of free land in the 19th century. Of course,” he explained, “that land did not necessarily mean security of body, but it did constitute a reserve of hope.”

Eisenhower said that no political system can “ignore hordes of people who through no fault of their own suddenly find themselves poverty stricken. . . . Mass production has wrought great things in the world, but it has created social problems that cannot be possibly met under ideas that were probably logical and sufficient in 1800.” As circumstances change, so must any government if it is to prove “durable,” he said, neatly summarizing the argument for progressive reform.

Chynoweth agreed that mass production “has created social problems that need a new approach. But why jump to the extreme New Deal view that the only way to find new approaches is from the Government?” he asked.

Although it had taken five letters, the elephant in the room —Ike’s predilection for New Deal social programs—was finally being named. The charge from the “radical [conservative] Republican” Chynoweth against the moderate, Middle Way Eisenhower was representative of the split that has divided the GOP for much of its history and continues in some fashion today.

Chyn’s New Deal charges also expressed the disappointment the Republican conservatives felt with Eisenhower when they realized the first GOP president in 20 years would not repeal FDR’s domestic achievements.

Ike Embraces New Deal Programs, Seeks to Chart a “Middle Way”

The degree to which Eisenhower accepted New Deal programs and his reasons for doing so have occupied historians and biographers since the 1940s. The consensus is that Eisenhower embraced the reforms as a political necessity. The New Deal had won broad acceptance from the American public. Higher expectations of the state were a political reality.

As Ike said in a November 1954 letter to his conservative brother Edgar Eisenhower, who had also accused the President of selling out to the New Dealers:

"Should any political party attempt to abolish social security, unemployment insurance, and eliminate labor laws and farm programs, you would not hear of that party again in our political history. There is a tiny splinter group, of course, that believes you can do these things. . . . [But] their number is negligible and they are stupid."

Other historians say the personally conservative President maintained the New Deal programs as a way to deflect more expansive social legislation by liberal Democrats. True, Ike’s Middle Way philosophy rejected the paternalism (and deficit spending) he saw inherent in a larger welfare state. And his occasional strident warnings against “creeping socialism” feed the conservative-expediency narrative.

But what both the realist and expedient arguments lack is the frontier factor.

President Eisenhower believed in a “floor over the pit of personal disaster,” as he described federal welfare programs, for the same fundamental reason President Roosevelt and other progressives did: the free land was gone.

Eisenhower probably first encountered the idea of the lost frontier’s consequences for government in the thick Turnerian air of early New Deal Washington. There the mid-level staff officer served under Army Chief of Staff Gen. Douglas MacArthur during the eventful first 100 days of the Roosevelt administration.

Ike was a close observer of the Washington scene, recording his impressions of the events of the day in his diary as well as the personalities he witnessed up close. Three of those figures—Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace, Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, and Gen. Hugh S. Johnson of the NRA—wrote books touting the New Deal as the solution to the frontier’s loss. The men also invoked the frontier’s closure frequently in articles and speeches. The attentive Eisenhower would have had difficulty avoiding the idea.

On his 67th Birthday, Ike Echoes FDR’s Lines

And although Eisenhower does not invoke the lost frontier rationale of the New Deal directly in his diary, he is most admiring in his praise for the New Deal’s grandest post-frontier scheme, the National Recovery Administration and its director, General Johnson.

“He seems to be a diamond in the rough,” Ike confided to his journal in an early assessment of the man. “[Johnson is] indomitable in will, ruthless in action, and possessed of a remarkable insight into American economic processes, their difficulties and their needs.”

Ike believed that “as in all other ideas of the President’s that have been translated into actual national effort—the announced objective [of the N.R.A.] is a most desirable one.”

Ike’s respect for Johnson grew even greater over the next six months. He wrote in November 1933, “The N.R.A. . . . has apparently been making progress more in line with what was expected, than has any other [New Deal program]. . . . The program of establishing industrial codes has occasioned lots of argument, but a lot of this can be undoubtedly attributed to Johnson’s proclivity for talking. He has a ready tongue and a facile imagination. . . . But the basic soundness of his methods (and I assume also of the principles of the N.R.A. effort) are demonstrated by the fact that in spite of all this ridicule the mass of our newspapers agree that the N.R.A. is really making headway.”

Relics of post-frontier New Deal ideas cropped up occasionally in Eisenhower’s public pronouncements during his White House years to suggest that his days in New Deal Washington were just as formative to his intellectual development as his time in General Conner’s “graduate school” in Panama.

But Ike’s frontier musings escaped the notice of the press then, and contemporary historians now, even as the parallels with New Deal thought stand in bold relief. His 67th birthday remarks, for example, celebrated in the very city where FDR made his signature campaign speech 25 years earlier, could have been clipped from Roosevelt’s script.

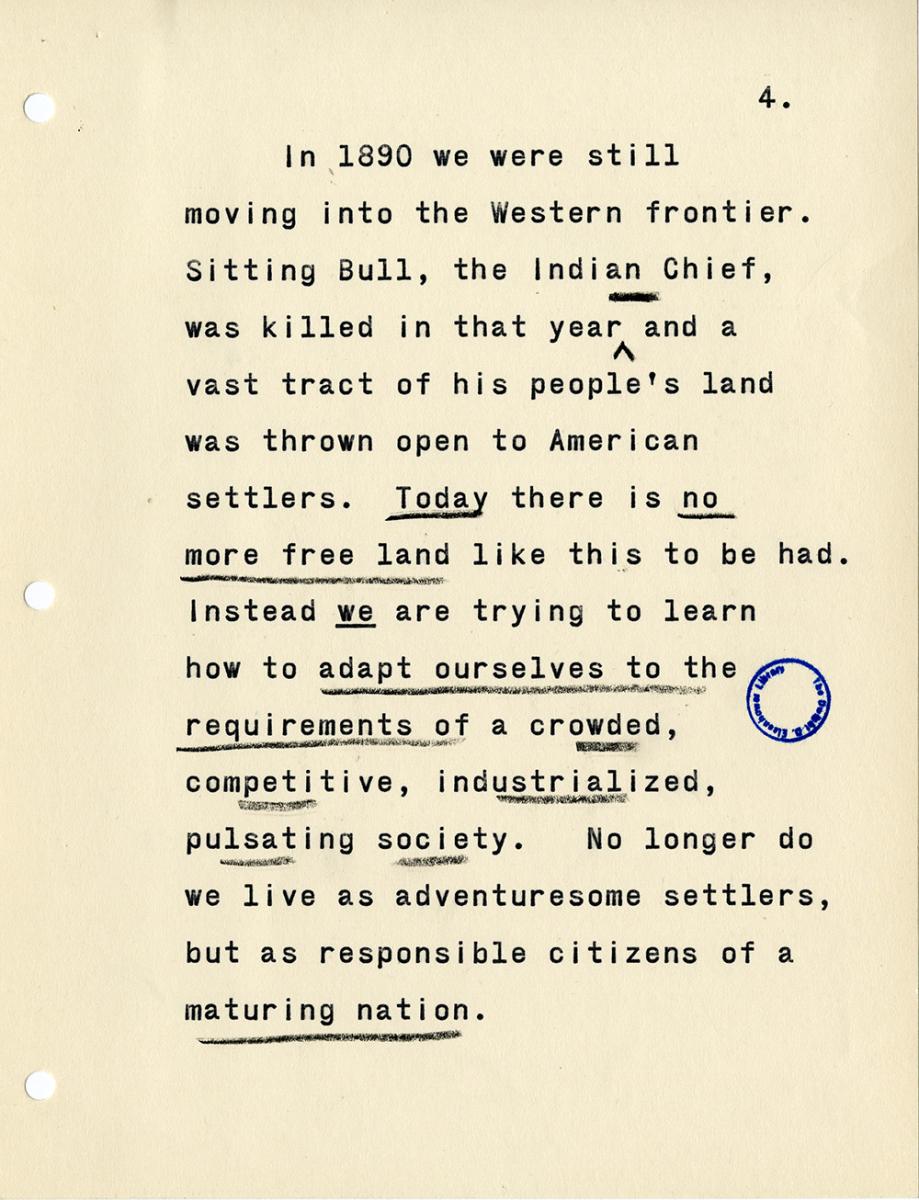

“In 1890 we were still moving in the Western frontier. Sitting Bull, the Indian Chief, was killed in that year—and a vast tract of his people’s land was thrown open to American settlers,” Ike said. “Today there is no more free land like this to be had. Instead we are trying to learn how to adapt ourselves to the requirements of a crowded, competitive, industrialized, pulsating society. No longer do we live as adventuresome settlers, but as responsible citizens of a maturing nation. Our tasks include the conserving of our resources, planning for the fullest use of our great strength, channeling our pioneer spirit into the endless task of making this Nation . . . a better place.”

Ike’s continuation and modest expansion of the New Deal was about more than accepting political reality or exercising political expediency. He shared a progressive interpretation of the American past with President Franklin Roosevelt and other prominent New Deal officials that led him to include federal welfare programs as part of his administration’s Middle Way. This is the significance of the frontier in Eisenhower history.

Timothy Rives is the deputy director and supervisory archivist of the Eisenhower Presidential Library, Museum, and Boyhood Home in Abilene, Kansas.

Note on Sources

The National Recovery Administration’s short life ended in 1935 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that its industrial code-making authority was unconstitutional. Although Eisenhower was critical of the centralizing tendencies of the New Deal and of “New Dealer” political types, he admitted that some of his programs were “New Dealish.” The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways continued and expanded President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s tradition of state-sponsored economic development. The interstate highway system, in fact, surpassed in size and scope all New Deal public works projects combined. See Jason Scott Smith, Building New Deal Liberalism: The Economy of Public Works, 1933–1956 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

The Eisenhower-Chynoweth correspondence is located in the Names Series of the Ann Whitman File, Dwight D. Eisenhower Papers as President Collection at the Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas. Eisenhower’s thoughts on the early New Deal are recorded in Eisenhower: The Prewar Diaries and Selected Papers, 1905–1941, ed. Daniel D. Holt and James W. Leyerzapf (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998).

“The Significance of the Frontier in American History” is widely available. Turner’s collected essays are found in Frederick Jackson Turner, The Frontier in American History (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1920 and 1962).

Although I did not quote from them directly, two books were important in framing this article: Theodore Rosenof ’s Dogma, Depression, and the New Deal (Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1975) explains how the idea of the frontiers closure undergirded New Deal economic ideas. David Wrobel’s The End of American Exceptionalism: Frontier Anxiety from the Old West to the New Deal (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1993) is indispensable for understanding the significance of the frontier’s loss in the American mind. Steven Kesselman’s article “The Frontier Thesis and the Great Depression” (Journal of the History of Ideas, April 1968, pp. 253–268) is just as important as the Rosenof and Wrobel works.

Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Commonwealth Club speech is included in his book Looking Forward (New York: John Day Company, 1933). Other New Deal frontier books include Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, The New Democracy (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1934); National Recovery Administration Director Hugh S. Johnson, The Blue Eagle: From Egg to Earth (New York: Doubleday, Doran and Company, 1935); Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace, New Frontiers (New York: Reynal and Hitchcock, 1934). Coincidentally, Milton Eisenhower, Ike’s youngest brother, served as the Agriculture Department’s chief spokesman under Wallace during Ike’s New Deal days in Washington. The New York Times notice of the Wallace book was included in the paper’s note of former President Herbert Hoover’s frontier/New Deal rebuttal The Challenge to Liberty (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1934). (“Mr. Hoover’s book is the one on the right,” the Times quipped.)

The lost frontier theme is also prominent in New Deal publicist Stuart Chase’s A New Deal (New York: Macmillan Company, 1932). Ray Allen Billington’s Frederick Jackson Turner: Historian, Scholar, Teacher (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973) is the biography of the man and his seminal idea.

My thanks to Robert Clark, Acting Director of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, and his staff for the copies of FDR’s Commonwealth Club address drafts. Additional thanks to David Nichols, Irwin Gellman, Bill Kauffman, and Bob Rives for finding this story not terrible.

PDF files require the free Adobe Reader.

More information on Adobe Acrobat PDF files is available on our Accessibility page.