Henry Ford: Movie Mogul?

Winter 2014, Vol. 46, No. 4

By Phillip W. Stewart

© 2014 by Phillip W. Stewart

When you remember Henry Ford, you probably think about the Ford Motor Company, cars, trucks, tractors, industry, Detroit, the five-dollar-a-day wage, or maybe the fact that Ford was the first to use the assembly line in automobile production.

However, there was a time between 1915 and the mid-1920s when Henry Ford was a movie mogul, overseeing the largest motion picture production and distribution operation on the planet. During those years, roughly one-seventh of America’s movie-going audience watched Ford films each week! The opening titles and subsequent subtitle cards of many of these silent movies were also translated into 11 different languages and shown around the world.

Today, these motion pictures and other films produced or acquired by the Ford Motor Company between about 1914 and 1954 are preserved at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

These films have superb historical value because they depict a broad range of subject matter. Almost every facet of the American experience from the mid-1910s through the early 1920s is portrayed, including business, city life, farming, manufacturing, news events, recreation, rural life, sports, transportation, and VIPs. In addition, as you would expect, the evolution of all industrial processes related to the automobile is extensively documented. Overall, the moving images contained in these films are truly Americana in motion.

Ford Buys Movie Camera, Consults with Edison

How did Henry Ford get into the movie business?

Well, that’s a story that began during the summer of 1913. Ford watched a movie production crew filming some of the operations of his Highland Park, Michigan, plant. He was in one of the scenes, which afforded him an up-close look at the movie-making process. Intrigued by the possibilities of using this technology to train his large workforce, Ford also thought it might be a way to communicate the news of the day to the public, to educate them about the world in which they lived, and of course, to illustrate the wonders of Ford automobiles.

In true Henry Ford style, he bought a movie camera that September, tinkered with it, started filming family and factory scenes, and consulted with visionaries like the inventor of the commercial motion picture, Thomas A. Edison.

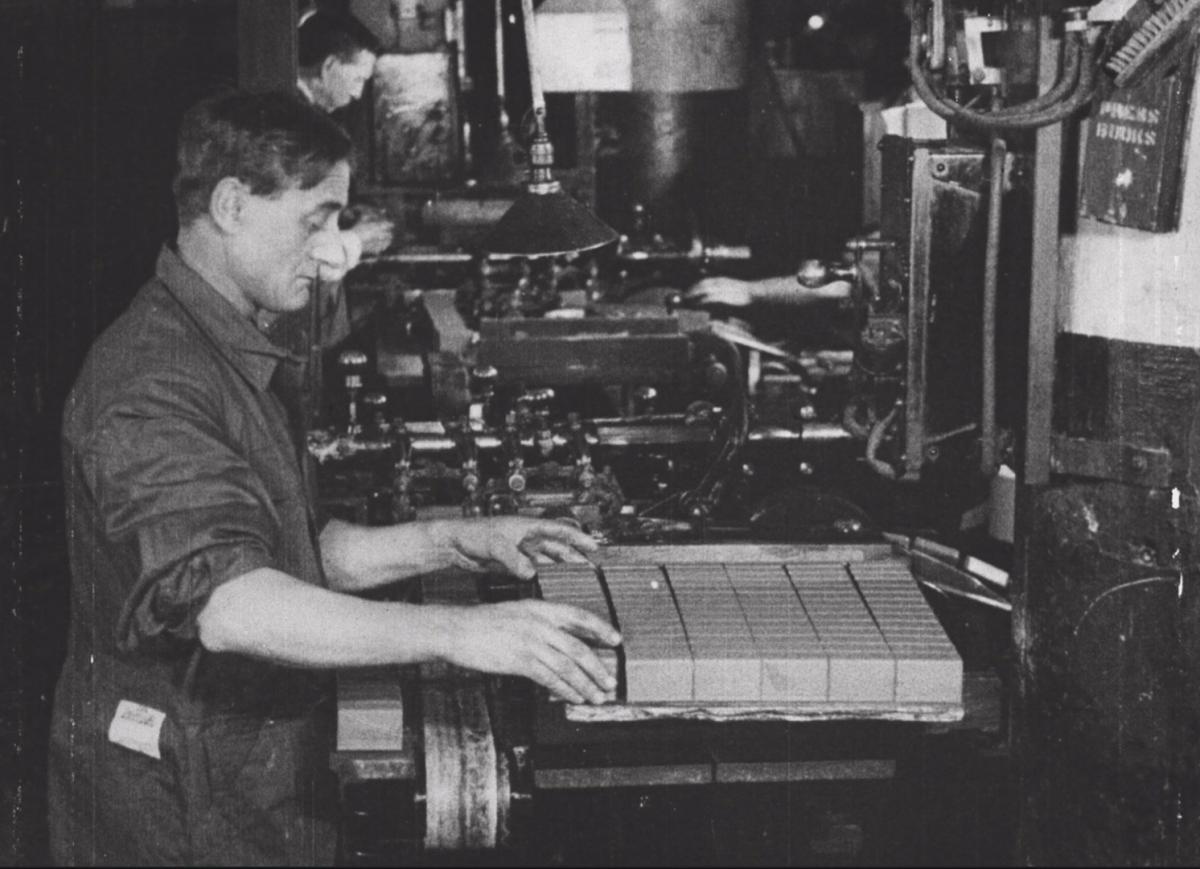

In April 1914, Ford told Ambrose Jewett, head of the company’s advertising operation, to set up a “moving-picture” department. Within months, the department acquired modern 35mm cameras, and the initial two-man staff grew to a talented crew of over 24. In addition, Ford built a state-of-the-art film-processing laboratory along with an equally impressive editing laboratory at the Highland Park plant.

Overall, it did not take long before the production capability rivaled that of any Hollywood studio. Thus, Henry Ford’s Motion Picture Laboratories were born, and Ford became the first American industrial firm to possess a full-service motion picture facility. The first film produced, How Henry Ford Makes One Thousand Cars a Day, was released later that summer. Sadly, this film is not part of the Ford film collection.

For the next two years, the laboratories’ primary production effort was the Ford Animated Weekly. Through the use of independent film distribution companies, and at no charge to the theater owners, movie houses around the country could show this 10- to15-minute informational newsreel.

The Weekly consisted of three to five stories that featured news events of the day, general interest items, and an occasional Ford Motor Company feature. The theater-going public responded quite favorably to stories like Helen Keller Visits with Henry Ford (1914, FC-FC-440); Thomas A. Edison, Guest of Honor, World’s Fair, San Francisco, California (1915, FC-FC-1172); Buffalo Bill Circus (1916, FC-FC-40), Galligan-Finney Wins Long Swim (1918, FC-FC-647); What Uncle Sam Had Up His Sleeve (1919, FC-FC-724); Between Friends—Juarez, Mexico (1920, FC-FC-291); and Henry Ford Pilots Big Locomotive (1921, FC-FC-2245). According to the July 1916 issue of the Ford Times, four million people in over 2,000 theaters regularly viewed the Weekly. Although the reel contained no advertising, a rendering of a Ford Model T radiator was the background for the film’s superimposed titles—subtle promotion at its best!

Ford Motor Co. Becomes World’s Largest Film Distributor

In late 1916, Henry Ford decided to slow down the hectic and expensive production pace required to make newsreels and replace the Animated Weekly with less costly “evergreen” historic and educational films (but as you can tell by the production dates noted above, the newsreels never really disappeared). The Ford Educational Weekly, which focused on short in-depth coverage of a single topic such as travel, industry, history, geography, and agriculture, was the result. The Detroit News reported that theater managers were very reluctant to show “dry, educational stuff” to their audiences.

However, film titles like A Visit With Luther Burbank, The Great American Naturalist (1917, FC-FC-2439); The “Tail” of a Shirt (1917, FC-FC-21); Heroes of the Coast Guard (1918, FC-FC-6); Bubbles, I’m Forever Using Soap (1919, FC-FC-2461); From Mud to Mug—The Story of Pottery Making (1919, FC-FC-2450); Chu Chu—Making Chewing Gum (1920, FC-FC-2489); Home of the Seminole (1920, FC-FC-2481); and Hurry Slowly (1921, FC-FC-2405) proved to be popular. As with the Animated Weekly, the Educational Weekly series was provided at no cost to the theater owners and was commercial free, except for a “Distributed by the Ford Motor Company” tagline on the bottom of the title cards.

In the September 20, 1917, issue of Ford’s in-house newspaper, The Ford Man, it was reported, “Over 1,000 miles of Ford films are shown weekly . . . in more than 3,500 theaters in the United States alone—likewise throughout the Dominions of Canada, the British Colonies, South Africa, India, Japan and most of the countries of Europe. It is a conservative estimate that between four and five millions of people are entertained by the pictures in this country every week.”

By mid-1918, Ford Motor Company had become the largest motion picture distributor in the world, spending $600,000 a year—the equivalent of more than $9.4 million today—on film production and distribution.

The production tempo of the Motion Picture Laboratories considerably increased soon after America entered World War I in April 1917. In addition to their usual tasks in support of the two Weekly series and plant operations, camera crews were now assigned to document Ford Motor Company’s wartime efforts. A sample of these projects include the construction of the new River Rouge plant (1917); the training of recruits at the U.S. Naval Training Station at Great Lakes, Illinois, which resulted in the multipart The Making of a Man-O-Warsman (1917); the building of a fleet of Ford-designed Navy submarine chasers, the Eagle Boat class, at the River Rouge plant (1918); the making and testing of the Liberty airplane motor (1918); and the testing of the Ford-designed three-ton Army tank (1918). The overall results from this wartime effort added 136 World War I–related titles to the laboratories’ film archive. Some of this footage was also used to produce stories for the Ford Animated Weekly.

Theater Owners Object to Ford’s Fees, Opinions

In an effort to increase its share of the theater-going audience, Ford hired the Goldwyn Distribution Corporation to circulate the Ford Educational Weekly shortly after the Armistice in November 1918.

By the end of 1919, the series appeared on over 5,200 movie screens every week. Soon thereafter, in an effort to offset production costs, Ford began to charge theaters a dollar a week to show the one-reeler. Theater owners noisily objected, and some stopped showing the reel.

Then, in May 1920, with the publication of anti-Semitic stories in the Ford-owned newspaper the Dearborn Independent, more theaters discontinued the title in protest. By August, distribution numbers had dwindled to about 1,300 theaters, and the Educational Weekly ceased production in December 1921.

Continuing Henry Ford’s focus on education, the newly formed Photographic Department, which combined motion picture and still photography operations, was directed to develop and produce the Ford Educational Library in 1920.

The films were designed for use in elementary and high schools, universities, churches, and other nonprofit educational institutions. A committee of college professors identified appropriate topics for the series that included transportation, agriculture, geology, medicine, safety, and civics.

A typical title is Journeys Through “The Valley of Hearts Delight” (1921, FC-FC-2437), which covers, in just under 12 minutes, the regional geography, people, and businesses of the city of San Jose, California, as well as the surrounding county of Santa Clara. Another representative film is The Hawaiian Islands (1924, FC-FC-484), which documents life in Honolulu, local Hawaiian and Japanese cultures, sugar cane production, and the making of poi. Altogether, roughly 50 titles were produced (and another 55 Educational Weekly films were later added) for the Library.

They were sold for 5 cents per foot or rented for 50 cents a day per reel. Although the Ford Educational Library was extensively promoted, it was not widely accepted and faded from sight during the waning months of 1925.

As noted earlier, while cameramen were busy creating informational and educational films, other Ford Photographic Department employees documented the activities of the company and captured Ford products in action. Some of this footage was used to produce public and workplace safety messages as shown in titles such as All for Safety (1918, FC-FC-222) and Safety First—We’re for Safety, Are You? (1926, FC-FC-4079).

Considerable footage also documented Ford airport operations, the manufacture of the Ford Tri-Motor airliner, and the Ford National Reliability Air Tours of 1925–1931. Wings of Progress—Commercial Airplane Reliability Tour for the Edsel B. Ford Trophy (1925, FC-FC-310) is a representative title.

Ford Uses His Films to Sell Automobiles

The largest percentage of the footage, however, was edited into promotional films for Ford branch sales managers and dealers throughout the country. An example is Keep the Boy on the Farm (1919, FC-FC-1514), which promoted the benefits of the new Fordson tractor over doing things the old way.

Other good examples are Golden Opportunity (1923, FC-FC-174), which extols the virtues of the Ford Weekly Purchase Plan, and The Source of the New Ford Car (1931, FC-FC-2993), which introduces the new V-8 engine and the latest production methods.

While most films ran 20–30 minutes, some were longer. The Ford Age (1923, FC-FC-139), which highlighted Ford’s worldwide industrial automotive prowess, is about an hour in length. These films were projected almost anywhere prospective buyers could gather: dealership showrooms, fraternal lodges, schools, recreation halls, county fairs, and even outdoors using the side of a building as a screen.

These films proved to be so popular, in both metropolitan and farming regions, that by the mid-1920s the Ford Motor Company estimated 2,500,000 people a month came to see them. In some of the more rural areas, the films were the first motion pictures that farmers and their families had ever seen.

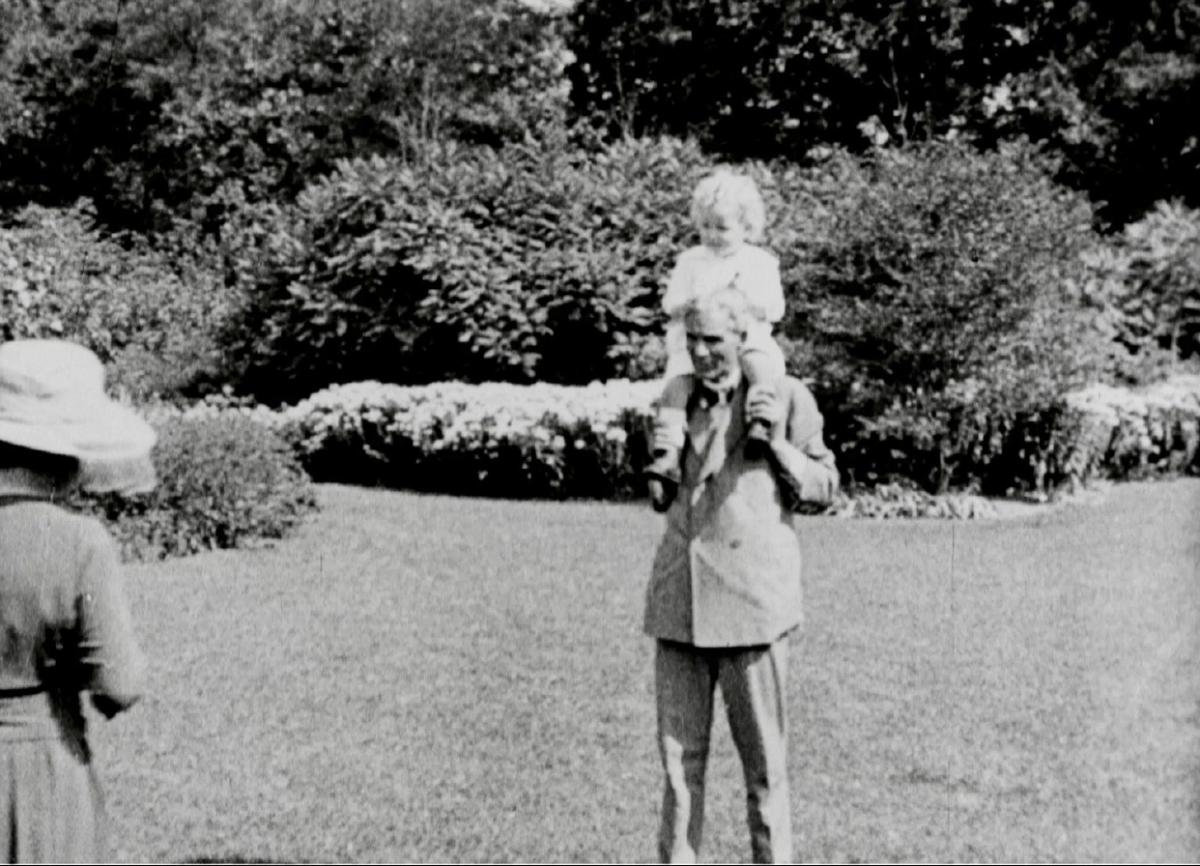

In addition to the variety of topics mentioned above, a significant subject of the movie camera was Henry Ford himself. One man, George Ebling, shot most of the photographs and motion picture footage of Henry and Clara Ford, their house at Fair Lane, their son Edsel and his wife Eleanor, their grandchildren, Ford’s close friends, visiting VIPs, camping trips, and travels.

From 1918 until his retirement in 1946, Ebling, or a team of assistants under his personal direction, captured the private and family life of Henry Ford. During those years, he filmed everything from the Ford grandchildren’s birthday parties to the family visit to the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

A fine example is Henry Ford and Grandsons (1920, FC-FC-4678), which was filmed on June 9 and stars 10-month-old Benson and an almost 3-year-old Henry Ford II. The following word picture, based on the “dope” sheet of the film, reveals the softer side of Grandpa Ford:

"In the garden at Fair Lane, Henry Ford carries Henry Ford II on his shoulders as Mrs. Ford stands alongside; Ford II enters and leaves the summer pavilion at Fair Lane; Ford II chases chickens in the chicken pen; Ford sits in the garden and plays with Ford II; Ford carries Ford II on his shoulders; . . . Ford II chases cows in a pasture; Ford and Henry Ford II on a swing; . . . Benson Ford sits on a table in the garden as Ford plays with him."

Ebling’s keen eye, adaptability to an often changing environment, and patience with the Ford family created an unexcelled historic visual record of hundreds of titles on thousands of feet of celluloid.

After suffering its worst sales numbers on record at the height of the Great Depression in 1932, the Ford Motor Company was forced to drastically reduce costs. As a result, it shuttered its airplane business and some other non-core endeavors, including the motion picture production facilities.

Thus, Henry Ford’s movie mogul days officially ended.

Ford’s Film Collection Includes Edison Donations

A greatly reduced Photographic Department staff continued to make films that documented the company’s products, operations, and special projects for internal use, while outside motion picture production companies were contracted to produce promotional and sales films.

Although the Ford Motor Company again established an in-house Motion Picture Department in 1952, it never achieved the internal or external audience impact that it had possessed when Henry Ford was the executive producer.

On November 28, 1962, the Ford Motor Company transferred all rights to their surviving 1.5 million feet of motion pictures to the National Archives, which cataloged the films as the “Ford Motor Company Collection, ca. 1903–ca. 1954.”

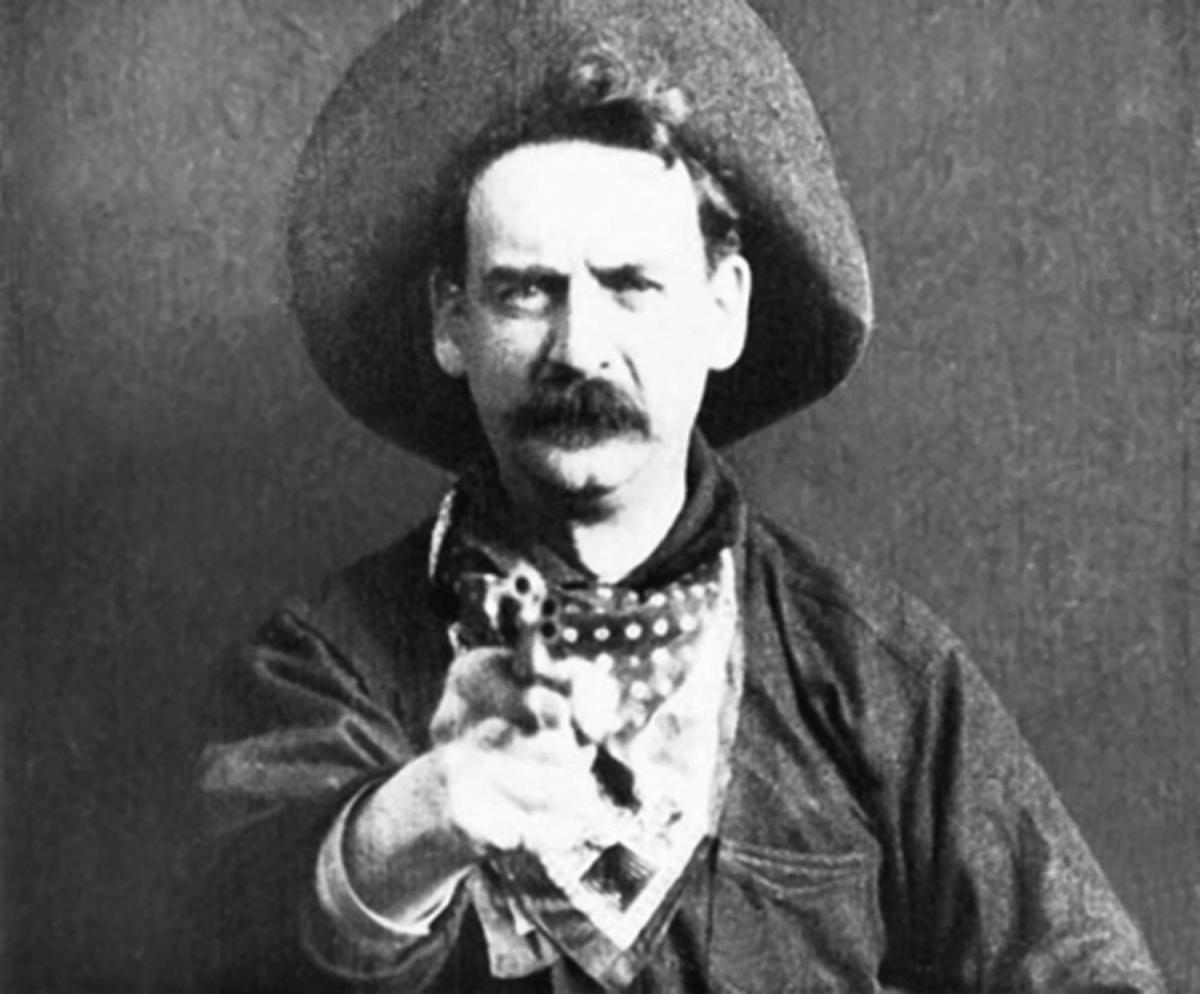

As an interesting side note, the year 1903 was chosen because the oldest title in the collection is The Great Train Robbery, which was distributed in December of that year by Edison Manufacturing Company. Thomas Edison, a close personal friend of Henry Ford, apparently gave copies of some of his early films to the Ford family at some point before his death in 1931.

Over the years, these titles found their way into the Photographic Department’s film vault and were then subsequently transferred to the National Archives along with all the other motion pictures.

The series title of the collection is aptly named “Motion Picture Films Relating to the Ford Motor Company, the Henry Ford Family, Noted Personalities, Industry, and Numerous Americana and Other Subjects, ca. 1903–ca. 1954.”

While these films are now owned by the American people and are copyright- and royalty-free, there are a few films in the collection that were produced by Ford contractors that may still have copyright or other use restrictions. The Motion Picture, Sound, and Video research room staff will be glad to address any questions regarding this matter.

According to the Online Public Access (OPA) catalog at Archives.gov, there are a total of 2,425 film titles on approximately 3,215 film reels in the collection. While none of the films listed in OPA contain scene or story descriptions at this point, more than 500 of them have been digitized for your viewing pleasure.

Because of the broad scope of their subject matter and the era in which they were filmed, the motion pictures contained in the Ford Motor Company Collection provide a unique look at America’s past. The moving images are truly Americana in motion, produced by the original movie mogul—Henry Ford.

Phillip W. Stewart is an award-winning author and recipient of the J. Franklin Jameson Archival Advocacy Award given by the Society of American Archivists for his work promoting motion picture film preservation and research at the National Archives. He is the author of 10 NARA-related film books and has contributed two previous articles to Prologue. His latest book, Battlefilm II: More Motion Pictures of the First World War Held in the U.S. National Archives, was published in July 2014.