The Army in the Woods

Records Recount Work of World War I Soldiers in Harvesting Spruce Trees for Airplanes

Fall 2014, Vol. 46, No. 3 | Genealogy Notes

By Kathleen Crosman

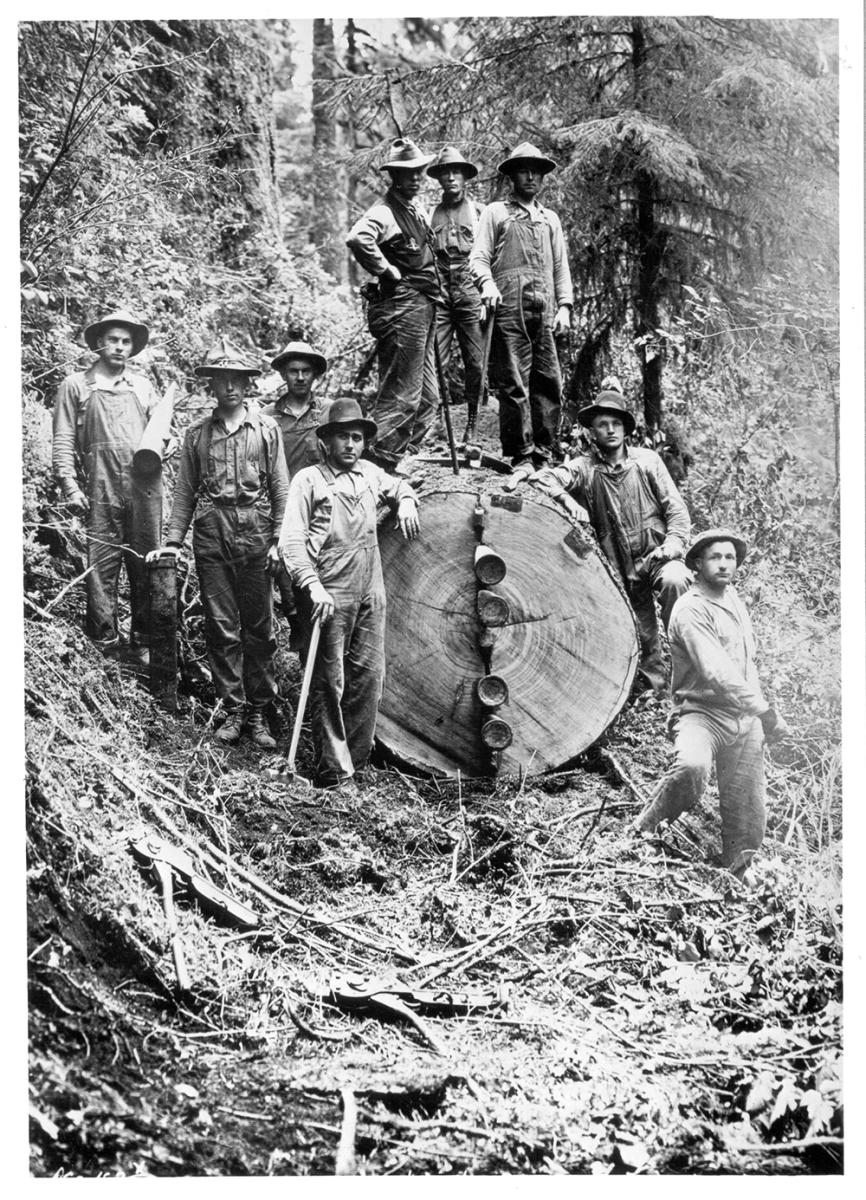

One of the more unusual duty stations for military personnel during World War I, and one that many genealogists might not be aware of, was in the forests and mills of the Pacific Northwest.

Men who had experience in the logging industry found themselves fighting the war not in the trenches in Europe but among the trees and lumberyards of Oregon and Washington.

By the time the United States entered the war in the spring of 1917, the Allies were in desperate need of flawless, lightweight, and strong lumber to build the aircraft needed to overcome the trench warfare stalemate and to battle the Red Baron over the skies of Germany.

In May of 1917, Maj. Charles R. Sligh, a reserve Army officer in charge of procuring wood, was sent to Washington and Oregon to evaluate the lumber situation. In a letter to the chairman of the Aircraft Production Board of the Council of National Defense he reported: “Every one has been taken aback by the magnitude of the combined demand. France and England each ask for as much as the present total production. Altogether the demand is more than trebeled [sic].”1

Sitka spruce, available only in the coastal forests of Oregon, Washington, British Columbia, and Alaska, was the ideal material. Getting Sitka spruce trees out of the forests and into the airplane factories was not easy. The lumber industry wanted and tried to meet the increased demand without government assistance. By November of 1917, about 2 million feet of spruce was being produced per month, but the U.S. Government was requesting an increase to 10 million feet per month in order to meet the demands of the Allies and its own military for wood to build airplanes.2

However, many stands of Sitka spruce were virtually inaccessible due to lack of logging roads, railroad tracks, and mills. There were also problems with the workforce. Labor groups were gearing up to demand better working conditions and threatening to strike. Given these challenges, it seemed an impossible task to increase lumber production fivefold.

So, the U.S. Army created the Spruce Production Division to unify all the groups involved—timber men, loggers, mill men—to expedite production. This special military command consisted primarily of draftees, some volunteers, and some regular Army troops. Most had prior experience in logging, milling, and associated necessary tasks, such as building railroad lines to transport the logs to the mills.

While many of the Spruce Squadrons worked in the woods, others supplied manpower to privately owned sawmills as well as those built and operated by the Spruce Production Division. The Traffic Section took care of the logistics of shipping the finished lumber to Atlantic ports for shipment overseas, which alone was a monumental task.

As Gerald W. Williams points out, between “November 1917 and October 1918, spruce production jumped from 2,887,623 to 22,145,823 board feet monthly. For the same twelve month period, a total of 143,008,961 board feet of spruce was shipped from the Northwest forests, including two small units from Alaska and California.”3 This is a remarkable achievement for a military division in existence for a mere 15 months.

The National Archives at Seattle holds roughly 187 cubic feet of Spruce Production records. They include the correspondence of 150 field squadrons and companies, district offices, the headquarters cantonment at the Vancouver Barracks in Vancouver, Washington, and the Spruce Production Corporation.

The Spruce Production Corporation was chartered in August 1918 in the State of Washington by John E. Morley, Prescott W. Cookingham, and John P. Murphy.4 The principal office was in Vancouver, Washington. With the war expected to last longer and with things well organized thanks to the work of the Spruce Production Division, the U.S. government decided to “de-militarize” many of the functions of the division. The real property of the division (railroads, mills, etc.) as well as functions such as traffic management were transferred to the corporation.

The material has been used by historians and other researchers interested in the World War I era; in the role of the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen, a “loyal” labor union established to maintain labor peace; and in the impact of the 1918 flu pandemic.

But the value of these records to genealogists has been limited to those who knew in which unit the research subject had served. Finding that information was complicated by the destruction of millions of military personnel records in the 1973 fire at the Military Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, Missouri. Army records suffered the worst damage, with 80 percent of the files for those discharged from 1912 to 1960 destroyed.

The Archives in Seattle has a complete roster of all military personnel in the Spruce Production Division as of November 1, 1918. While this is merely one span of time, it is at least an entry point that can be used to begin research. The roster is arranged by first letter of the surname and then by unit, and it lists each man’s age, rank, duty assignment, and home address.

The National Archives at Seattle hopes to have volunteers enter the information into a searchable database to improve access in the future. The roster by itself provides a certain amount of information. It also serves as an index to the correspondence files for a specific Spruce Production Squadron.

These correspondence files were referred to regularly by the squadron commander and by the squadron clerk. Correspondence between a squadron and headquarters can be found going back and forth many times. In order to keep track of the correspondence, each squadron clerk maintained numbered correspondence files and then tracked the correspondence in one or more correspondence index books.

These index books had subject and name entries with the correspondence number on alpha index pages in the front of the book. In some books there is also a numeric list of the correspondence on blank pages in the back with brief summaries of each memo/letter.

These examples are soldiers whose names showed up in squadron correspondence index books:

In March 1918, Pvt. Edward Jensen requested a five-day furlough to return to Seattle. He had been required under the compulsory allotment law to provide for his ex-wife, who had deserted and then divorced him. He had recently received information from his wife’s mother that she had remarried in King County. If true, he could terminate his allotment. Jensen requested the furlough “for the purpose of securing, from the County Clerk of King County, this final proof of his exemption from the Compulsory Allotment Law.”5

- Pvt. Arthur W. Anderson requested a furlough in May 1918 to return to Great Falls, Montana, to “straighten out his affairs on his homestead.”6

- On April 25, 1918, Pvt. Arlis A. McMillen requested a 30-day furlough to return home to recover from a work injury. McMillen was a 26-year-old wood splitter from Edina, Missouri. He had been working in the woods and hit his ankle with his axe. Fortunately, he cut off just a part of the bone on his ankle and only needed to be off his feet for a month.7

- Pvt. Raymond L. Renwick was officially attached to the 30th Spruce Squadron based in Vancouver, Washington, but he spent much of 1918 attached to the 42nd Spruce Squadron based in Aberdeen. His particular duty was to drive and maintain the Ford Touring Car assigned to 1st Lt. Donald G. Hugo, the medical reserve corps surgeon for the area.8 His heart, however, was elsewhere. Renwick applied repeatedly to take the examination for entrance to the Flying Service, and his local commanders repeatedly recommended him for this opportunity.9 Still, nothing came of their attempts. The best they were able to do was promote him, in November 1918, to private first class.10

- In early 1918, Dawn L. Diffin, wife of Robert A. Diffin, wrote to headquarters to complain that she had not been getting her husband’s allotment money. Robert Diffin had originally been with the 42nd Spruce Squadron but had subsequently been transferred to the Vancouver Barracks. On March 5, the commander of the 42nd responded that: “Diffin had an allotment made out in favor of his wife which was entered on our December Pay Roll which also showed him last paid to October 31, 1917. So he has done all he could. He received no further pay until after we received our January Pay Roll which was toward the end of February. Diffin, I think, has been short of money.”11

- On September 13, 1918, Pvt. Major F. Ball requested a discharge on “account of the illness and age of my father which renders him unfit for work; the drafting of my brother-in-law into the service; the illness of my mother and the consequent leaving of the care of seven children (all under the age of ten years) and the farm to my wife, who is strictly dependent upon me for support.”12

The Spruce Production Division grew from nothing to a maximum size of roughly 30,000 men between November 1917 and November 1918. Given the large number of soldiers who served in the Spruce Production Division, few are mentioned by name in the correspondence held in our collections. The examples above are of soldiers not only mentioned by name but also listed in the squadron index books by name.

The following soldiers are mentioned by name but not indexed by name. The only way to find this correspondence is to know in which squadron the soldier served.

- In October 1918, squadrons were asked to provide a list of all members of the Jewish faith in their units. The report of the 42nd Squadron contained only the name of Irving Aaron, a 22-year-old private from Virginia, Minnesota.13

- Memos listing men being transferred into or out of a unit were not indexed in the squadron index books. On April 20, 1918, a total of 32 men were transferred into the 42nd Spruce Squadron.14

- Sometimes soldiers were transferred to other squadrons or to the Vancouver Barracks before their pay checks were received at their original squadron. On April 24, 1918, the commander of the 42nd Squadron sent a cover memo with the paychecks for the seven men listed who had been transferred to the Vancouver Barracks.15

- Periodically, squadron commanders were asked to report the names of men fit for overseas duty. In July 1918, the commander of the 78th Spruce Squadron, based in Astoria, Oregon, sent a list of 13 men physically fit for overseas duty and also noted the names of two men who were not fit for overseas duty.16

- Standardized forms were used to report the names and pay for all soldiers on duty in the various logging and milling companies.

While even more challenging to use, one other group of records may contain information about a particular soldier a researcher might be looking for. The Spruce Production Division was headquartered in Vancouver, Washington, at Vancouver Barracks. The decimal correspondence of the Vancouver Barracks consists of letters, lists, memorandums, orders, reports, summaries, and telegrams pertaining to its administration and operations and to its interactions with the local community and with the families of soldiers within the division.

While much of the decimal correspondence would not contain information on individual soldiers, the 200 series pertains to personnel matters, including transfers and promotions, reassignments, pay and accounting actions, transportation, and rations and supplies. It also contains letters from soldiers’ families on matters such as pay allotments, War Risk Insurance claims, and the general welfare of soldiers. The challenge with this series is that there is no name index. The decimal subject code provides the only guidance.

Searching for your soldier in the Spruce Production Division can be challenging, but the effort can be rewarding—even if you do not find him. The squadron correspondence tells a story of these soldiers’ lives in the woods or in the mills—their pay, their drills, their complaints, their requests. The correspondence documents the routines of military operations even in the middle of the forest, the mix-ups that took place in a military organization that was thrown together quickly, and the semicivilian feel of a military unit in which many of the draftees did not go through basic training and were working on civilian tasks.

If your hunt for a World War I veteran leads you to Oregon or Washington, especially if your veteran had a logging or milling background, you should consider looking into these records.

This article was initially published in the Oregon Historical Quarterly, vol. 112, no. 1 (Spring 2011), and is reproduced here with permission.

Kathleen Crosman is an archivist with the National Archives at Seattle. She received her MLIS from the University of Washington and her Certificate in Archives and Records Management from Western Washington University.

Notes

1. Spruce Production History, Rough Draft, box 1, Records of the Spruce Production Divison, Records of the Army Air Forces, Record Group (RG) 18, National Archives at Seattle (NAS).

2. Ibid.

3. Gerald W. Williams, “The Spruce Production Division,” Forest History Today (Spring 1999), available online at www.foresthistory.org/publications/fht/fhtspring1999/fhtspruce.pdf (accessed July 9, 2014).

4. Articles of Incorporation, in Corporate Documents, box 1, Records of the Spruce Production Divison, RG 18, NAS.

5. Correspondence No. 526, 42nd Spruce Squadron, Squadron Correspondence, box 86, in ibid.

6. Correspondence No. 1325, 42nd Spruce Squadron, Squadron Correspondence, box 89, in ibid.

7. Correspondence No. 1049, 42nd Spruce Squadron, Squadron Correspondence, box 88, in ibid.

8. Correspondence No. 1110, 42nd Spruce Squadron, Squadron Correspondence, box 88, in ibid

9. Correspondence Nos. 1111, 1248, 42nd Spruce Squadron, Squadron Correspondence, box 88, and Correspondence Nos. 341, 392, 30th Spruce Squadron, Squadron Correspondence, box 50, in ibid.

10. Correspondence No. 2166, 30th Spruce Squadron, Squadron Correspondence, box 52, in ibid.

11. Correspondence No. 491, 42nd Spruce Squadron, Squadron Correspondence, box 86, in ibid.

12. Correspondence No. 1680, 42nd Spruce Squadron, Squadron Correspondence, box 90, in ibid.

13. Correspondence No. 1753, 42nd Spruce Squadron, Squadron Correspondence, box 90, in ibid.

14. Correspondence No. 1003, 42nd Spruce Squadron, Squadron Correspondence, box 88, in ibid.

15. Correspondence No. 1027, 42nd Spruce Squadron, Squadron Correspondence, box 88, in ibid.

16. Correspondence No. 156, 78th Spruce Squadron, Squadron Correspondence, box 165, in ibid.

PDF files require the free Adobe Reader.

More information on Adobe Acrobat PDF files is available on our Accessibility page.