"OK, We'll Go"

Just What Did Ike Say When He Launched the D-day Invasion 70 Years Ago?

Spring 2014, Vol. 46, No. 1

By Tim Rives

An elusive D-day mystery persists despite the millions of words written about the Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944: What did Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower say when he gave the final order to launch the attack?

It is puzzling that one of the most important decisions of the 20th century did not bequeath to posterity a memorable quote to mark the occasion, something to live up to the magnitude of the decision. Something iconic like Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s vow to the people of the Philippines, “I shall return.”

The stakes of the invasion merited verbal splendor if not grandiloquence. If Operation Overlord failed, the Allies might never have won the war. Yet eyewitnesses to Eisenhower’s great moment of decision could not agree on what he said.

As for Eisenhower, he could not even agree with himself: He related five versions of his fateful words to journalists and biographers over the years. Even more mysteriously, he wrote five different versions of the statement in a 1964 article commemorating the 20th anniversary of D-day.

To put his words—whatever they may have been—into context, the high drama of the meetings leading up to the invasion decision 70 years ago bears repeating.

Eisenhower Relies on His Weatherman

All the elements for the D-day attack were in place by the spring of 1944: more than 150,000 men, nearly 12,000 aircraft, almost 7,000 sea vessels. It was arguably the largest amphibious invasion force in history. Every possible contingency had been planned for. Every piece of equipment issued. Every bit of terrain studied. The invasion force was like a coiled spring, Ike said, ready to strike Hitler’s European fortress.

All it waited for was his command, as Supreme Commander, Allied Expeditionary Force, to go.

But for all the preparation, there were critical elements Eisenhower could not control—the tides, the moon, and the weather. The ideal low tidal and bright lunar conditions required for the invasion prevailed only a few days each month. The dates for June 1944 were the fifth, the sixth, and the seventh. If the attack was not launched on one of those dates, Ike would be forced to wait until June 19 to try again. Any wait risked secrecy. Delay would also cut into the time the Allies had to campaign during the good summertime weather.

“The inescapable consequences of postponement,” Ike wrote in his 1948 memoir Crusade in Europe, “were almost too bitter to contemplate.”

Ike and his staff began meeting in early June to choose the final invasion date, a day now contingent on the best weather forecast. The setting was Southwick House, near Portsmouth, in southern England. The conference room where they met was large, a 25-by-50-foot former library with floor-to-ceiling French doors, dark oak paneling, and a blue rug on which Ike would pace anxiously in the days leading up to the invasion. Empty bookshelves lined the room, a forlorn reminder of its now decidedly unliterary purpose.

Ike, his commanders, and his weather team, led by Group Captain J. M. Stagg, met in the library twice a day, at 4 a.m. and 9:30 p.m. On the evening of Saturday, June 3, Stagg reported that the good weather England experienced in May had moved out. A low was coming in. He predicted June 5 would be cloudy, stormy, windy, and with a cloud base of zero to 500 feet. That is, it would be too windy to disembark troops in landing craft and too cloudy for the all-important preparatory bombardment of the German coastal defenses. The group reconvened early the next morning to give the weather a second look. The forecast was no better, and Eisenhower reluctantly postponed the invasion.

“How long can you . . . let it hang there.”

The group gathered again at 9:30 the evening of Sunday, June 4. Ike opened the meeting and signaled for Stagg to begin. Stagg stood and reported a coming break in the weather, predicting that after a few more hours of rain would come 36 hours of clearer skies and lighter winds to make a June 6 invasion possible. But he made no guarantees.

The commanders debated the implications of the forecast. They were still struggling toward consensus when Eisenhower spoke.

“The question,” he said, “is just how long can you keep this operation on the end of a limb and let it hang there.”

The order, he said, must be given. Slower ships received provisional orders to sail. But Ike would wait until the next morning to make the decision final. He ordered the men to return again in the early hours of June 5.

Ike rose at 3:30 and traveled the muddy mile from his camp to Southwick House through withering rain and wind. Stagg had been right. If the invasion had started that morning, it would have failed.

Ike started the meeting. Stagg repeated his forecast: the break in the weather should hold. His brow as furrowed as a Kansas cornfield, Eisenhower turned to each of his principal subordinates for their final say on launching the invasion the next day, Tuesday, June 6, 1944. Gen. Bernard Law Montgomery, who would lead the assault forces, said go. Adm. Sir Bertram Ramsay, the Naval Commander in Chief, said go. Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory, the Air Commander in Chief, said go.

Eisenhower stood up and began walking back and forth on the war room’s blue rug, pondering the most important decision of his life and the fate of millions. It was now up to him. Only he could make the decision. He kept pacing, hands clasped behind his back, chin on his chest. And then he stopped. The tension left his face. He looked up at his commanders and said . . . what?

This is where history draws a blank. What did Ike say when he launched the D-day invasion? Why is there no single, memorable quote?

Ike Gave the Order, But What Did He Say?

The eyewitnesses offer answers but little help. Of the 11 to 14 men who attended the final decision meeting—the number is also in dispute—only four men besides Eisenhower reported what they believed were the Supreme Commander’s historic words. The accounts of three witnesses appeared in memoirs published between 1947 and 1969.

Lt. Gen. Walter Bedell Smith, who as Ike’s chief of staff probably spent more time with him than anyone else during the war, reported, “Well, we’ll go!” in his memoir, Eisenhower’s Six Great Decisions (1956). Maj. Gen. Francis De Guingand, Field Marshal Montgomery’s chief of staff, noted, “We will sail tomorrow” in Operation Victory (1947). In Intelligence at the Top (1969), Maj. Gen. Kenneth Strong, whom Ike described as the best intelligence officer he had ever known, said, “OK, boys. We will go.”

Admiral Ramsay died in an airplane crash during the war and left no memoir. His version survives through the reporting of Allan Michie of Reader’s Digest. Michie published the story behind the Ramsay quote in his 1964 book, The Invasion of Europe. It is the best account available to historians of a contemporary journalist attempting to verify Ike’s words.

Michie writes how he began his quest for the elusive phrase on June 5, pressing Ramsay for the moment-by-moment details of the final meeting at Southwick House. Ramsay was fluently unrolling his story until he reached the moment of Ike’s decision. There he stalled. “What did Eisenhower say? What words did he actually use?” Michie asked. “I can’t quite remember,” Ramsay said, but it was “a short phrase, something typically American.” Michie peppered Ramsay with possibilities, all of which the admiral dismissed until the correspondent hit upon “Ok, let ’er rip.” Ramsay tentatively confirmed it, but warned Michie that he would need Eisenhower’s agreement.

Michie hurried to Ike’s command trailer and asked an aide for Eisenhower’s imprimatur. The aide returned a few minutes later and told Michie that if he and Ramsay agreed on the phrase, it was good enough for Ike. A military censor forced Michie to get the quote reconfirmed a few days later when he attempted to cable his article to Reader’s Digest. Eisenhower obliged, and “Ok, let ’er rip” appeared in the magazine’s August 1944 issue.

A Much-Used “OK, We’ll Go” Picked Up by Some Historians

Michie’s story impressed Eisenhower’s British Military Assistant, Col. James Gault, who noted the article in his diary. Gault lent his diary to Kenneth S. Davis, an early Eisenhower biographer, who arrived at Ike’s headquarters in August 1944.

Notes from the diary found in Davis’s personal papers confirm that he was aware of Michie’s version, but he published his own D-day quote in his 1945 book, Soldier of Democracy. “All right,” Davis writes, “We move.” Davis presumably got this from Eisenhower in one of his three interviews with the general that August, but his papers do not contain verbatim notes.

The Davis book was backed by Milton Eisenhower, Ike’s youngest brother. The president of Kansas State College (now Kansas State University), Milton recruited Davis to write the biography “so that at least one good one is produced.” The book, Milton assured Ike, “promises to be one of real value in the war effort on the home front and to have real historical information.”

Although Ike would have qualms with Davis’s book—he thought the author overemphasized class conflict in his Abilene, Kansas, hometown—he had no hesitation later in recommending it to a man who “wanted to know what your thoughts were at 4 a.m. on that day when you had to make the great decision.” Additionally, while Eisenhower made 250 annotations in his copy of the book, he did not comment on Davis’s version of the quote.

Another wartime writer, Chester Wilmot of the BBC, reports “Ok, we’ll go” in The Struggle for Europe (1952). Wilmot interviewed Eisenhower twice—on August 11, 1944, and again on October 16, 1945. He submitted his questions to the general before the 1945 interview. Question three asked specifically for the details of the June 5 meeting. Perhaps he got them, but like Davis, Wilmot’s interview notes contain no direct evidence of his quote.

Nevertheless, Wilmot’s version is confirmed by Eisenhower in the CBS documentary “D-Day Plus 20 Years,” an anniversary special filmed on location in England and France in 1963. It aired on June 6, 1964. Walter Cronkite interviewed Ike in the Southwick House war room where he made the decision. In this interview, Ike said, “I thought it [the likely weather] was just the best of a bad bargain, so I said, ‘Ok, we’ll go.’”

Eisenhower Never Challenges Different Versions of Quote

Eisenhower had the chance to amend his words when he reviewed galley proofs of the interview transcripts prepared for publication in the New York Herald Tribune by historian Martin Blumenson. Ike made almost 80 revisions to the text but did not touch the D-day quote.

A similar version of the Wilmot/Cronkite quote is Stephen Ambrose’s “Ok, let’s go,” which appears in his many World War II books. In The Supreme Commander (1970), Ambrose claimed he garnered it from Eisenhower during an October 27, 1967, interview. “He was sure that was what he said.” But Ike’s post-presidential records disprove his claim. He didn’t see Ambrose that day. He was playing golf in Augusta, Georgia, not revisiting the past. Furthermore, in Ambrose’s book, D Day: June 6, 1944, The Climatic Battle of World War II (1994), he mistakenly attributes the quote to the 1963 Cronkite interview.

The confusion over Ike’s D-day words would spread beyond the English-speaking world. Claus Jacobi of the German magazine Der Spiegel interviewed Eisenhower at his Palm Desert, California, vacation home on May 6, 1964. His version approximates the Wilmot/Cronkite quote, adding one word: “Ok, we’ll go ahead.” Eisenhower reviewed Jacobi’s article before publication, but as usual did not comment on the quote, although he did strike out the statement that the Allies would have dropped atomic weapons on Germany had the invasion failed.

Even Eisenhower Himself Couldn’t Decide on Wording

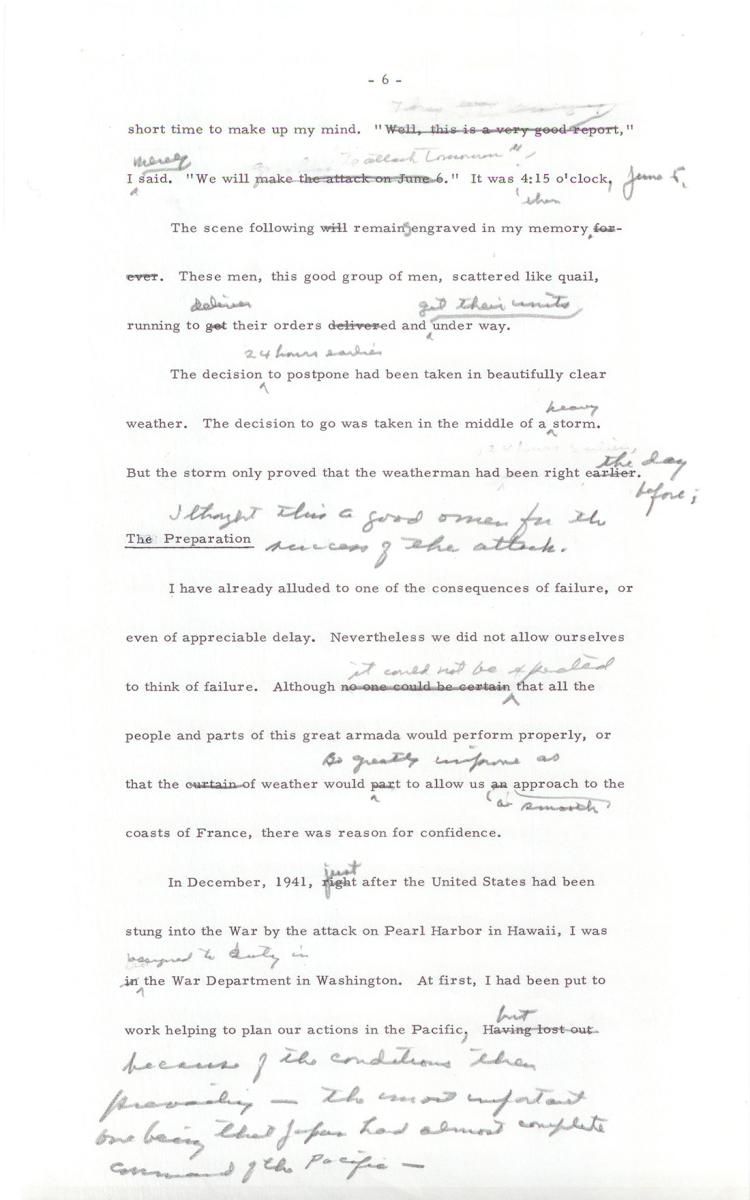

Eisenhower never once commented on or corrected the different quotes he found in the work of journalists, biographers, or former comrades. But neither did he use them in his most detailed account of the June 5 meeting. Nor for that matter did he use his own most recent statement. Instead, Eisenhower wrote five different versions of the quote in drafts of a 1964 article for Paris Match.

The Paris Match article was about D-day, but it had a contemporary strategic purpose as well. France was becoming more and more independent of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization at the time. Reminding the French of their shared sacrifice during the Second World War might strengthen their bond with the Allies. As Jean Monnet, a leading advocate for European unity, said to Ike in a telegram: “I feel sure that an article by you at this moment on the landing would be politically most important.”

Given this importance, Ike presumably put a lot of thought into the story, which either makes the various versions it contains more perplexing, or it explains them. Eisenhower may have been searching for just the right words to inspire French readers.

In his notes for the article, Ike wrote, “Yes, we will attack on the 6th.”

In the first full draft of the story, he said, “Yes, gentlemen, we will attack on the 6th.”

In the penultimate draft, Ike scratched this out and wrote, “Gentlemen, we will attack tomorrow.”

Elsewhere in the draft, referring back to his decision, he said, “We will make the attack on June 6,” which he then marked out and wrote, “We will attack tomorrow.”

In the final draft he makes two references to the decision: “We will attack tomorrow” and “Gentlemen, we will attack tomorrow,” thereby demonstrating once again his apparent lack of concern with exactly what he said in the early morning hours of June 5, 1944.

The Paris Match article appeared within days of the New York Herald Tribune series, the CBS airing of “D-Day Plus 20 Years,” and the Der Spiegel article. Three different Eisenhower quotes in three languages were put before the international public at the same time. The quote was lost before there was even a chance for it to be lost in translation.

What accounts for all these versions of Ike’s D-day words? The historian David Howarth perhaps captured it best in his description of the June 5 meeting:

"Nobody was there as an observer. However high a rank a man achieves, his capacity for thought and feeling is only human, and one may imagine that the capacity of each of these men was taxed to the limit by the decision they had to make so that none of them had the leisure or inclination to detach his mind from the problem and observe exactly what happened and remember it for the sake of historians."

Confusion Also Reigns Over Time of Decision

The stress confounding the commanders obscured other key details of the meeting: What time did they meet? Who was there? Was Ike sitting or pacing when he made the decision? How long did it take him to make up his mind?

Various eyewitnesses place the June 5 meeting at 4:00, 4:15, and 4:30 a.m. Eisenhower was nearly as inconsistent with the time as he was with his words. In the early Paris Match drafts, he states he made the final decision at 4:00, but in the last draft he says the meeting started at 4:15. His 1948 war memoir records that he made the decision at 4:15. Field Marshal Montgomery puts the decision at 4:00 in his 1946 account of the meeting, but at 4:15 in his memoir 12 years later. Another six eyewitnesses who noted the time of the meeting cast one vote for 4:00, four for 4:15, and one for 4:30. Francis De Guingand omits the June 5 date altogether and places the final decision on the night of June 4.

The identity of the eyewitnesses is questioned by . . . the eyewitnesses.

A June 5, 1944, memorandum by operations planner Maj. Gen. Harold Bull names Eisenhower, Montgomery, Ramsay, Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder, Leigh-Mallory, Air Vice Marshal James Robb, Rear Admiral George Creasy, Smith, Strong, and De Guingand as present. In some accounts Stagg attended the meeting but left before the decision was made. Air Vice Marshal Robb had his own list, which adds Gen. Sir Humfrey Gale, Ike’s chief administrative officer, and Air Vice Marshal H.E.P. Wigglesworth. Eisenhower is alone in including Gen. Omar Bradley in his account of the final meeting, but Bradley wrote in his 1951 war memoir that he was aboard the USS Augusta at the time of Ike’s decision.

The eyewitnesses—a designation rapidly losing its force—further disagree on Ike’s movements during the final decision meeting. Eisenhower paced the room in the account shared above, which came from General Strong. But General Smith asserts that Ike sat. But was it on a sofa, as Smith writes? Or at a conference table, as General De Guingand says? Or in an easy chair, as the weatherman Stagg remembers?

And how long did it take Eisenhower to make up his mind once his commanders had given their opinions? Was it the 30 to 45 seconds he recalled in 1963? Or “a full five minutes” as Smith recorded in his 1956 memoir?

Eisenhower pondered these discrepancies in later years. While he did not directly invoke David Howarth’s “fog of war” explanation in his unpublished 1967 essay, “Writing a Memoir,” he agreed with its implications. He wrote:

"When accuracy is all important, memory is an untrustworthy crutch on which to lean. Witnesses of an accident often give, under oath, contradictory testimony concerning its details only hours later. How, then, can we expect two or more individuals, participants in the same dramatic occurrence of years past, to give identical accounts of the event?"

With Eisenhower, There Were No Theatrics, Just Modesty

But there is more to the mystery of Ike’s D-day words than the inability of memory to preserve the past. Eisenhower’s humble character contributes to the riddle. And while his character alone cannot solve the mystery, it may explain why there is no single, memorable quote.

Ike disdained pomposity in word and manner. He disliked the “slick talker” and the “desk pounder.” The histrionic gesture or declamation just wasn’t in him.

As his biographer Kenneth S. Davis writes, “There was nothing dramatic in the way he made [the decision]. He didn’t think in terms of ‘history’ or ‘destiny,’ nor did there arise in him any of that grandiose self-consciousness which characterizes the decisive moments of a Napoleon or Hitler.”

Everything about Eisenhower was restrained, D-day historian Cornelius Ryan adds. “Apart from the four stars of his rank, a single ribbon of decorations above his breast pocket and the flaming shoulder patch of SHAEF, Eisenhower shunned all distinguishing marks. Even in the [command] trailer there was little evidence of his authority: no flags, maps, framed directives, or signed photographs of the great or near-greats who visited him.”

There is no memorable quote, in other words, because of Eisenhower’s good old-fashioned Kansas modesty. He did not have the kind of ego that spawns lofty sentiments for the press or posterity. Ike was a plain speaker from the plains of America’s heartland. Contrast this with Douglas MacArthur, whose “I shall return” was carefully composed for press and posterity. (The U.S. Office of War Information preferred, “We shall return” but lost the fight to the lofty MacArthur.)

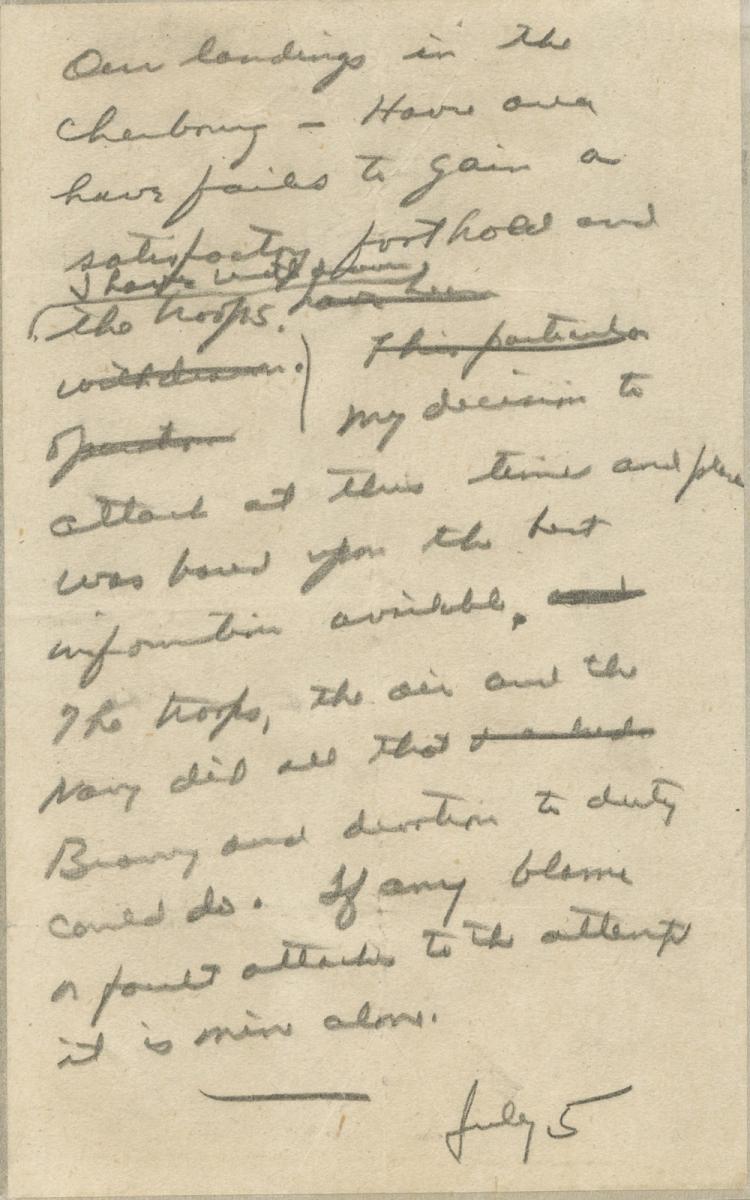

Eisenhower’s self-effacing character is also revealed in his other D-day words, words he never intended anyone to hear. The words show he was far more concerned with taking responsibility for failure than with glorying in whatever success crowned D-day. During the somber lull between the decision and the invasion, Ike scribbled a quick note and stuffed it in his wallet, as was his custom before every major operation. He misdated it “July 5,” providing more evidence of the stress vexing him and his subordinates. He found the note a month later and showed it to an aide, who convinced him to save it.

The note said simply:

"Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based upon the best information available. The troops, the air and the Navy did all that Bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone. Eisenhower’s D-day worries lay with the consequences of his decision, not the style in which it was uttered. And while the result of his D-day decision is well known, his words unleashing the mighty Allied assault on Normandy will remain a mystery, just the way he would have wanted it."

Tim Rives is the deputy director of the Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum in Abilene, Kansas. He earned his master of arts degree in American history from Emporia State University in 1995. He was with the National Archives at Kansas City from 1998 to 2008, where he specialized in prison records. This is his fifth article written for Prologue.

Note on Sources

The faint trail connecting the sources used for this article begins in the holdings of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum in Abilene, Kansas. The sole mention of his Last Words in the Pre-Presidential Papers of Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1916–1952, appears in the Principal Files series. A similar lone reference is found in the White House Central Files, President’s Personal Files series. It is not until you examine Ike’s Post-Presidential Papers, 1961–1969, that the bread crumbs start appearing at regular intervals. Records relating to the D-day invasion and his fateful words are found in numerous folders in the series 1963 and 1964 Principal Files. His essay on the difficulties of memoir writing is in the Augusta-Walter Reed series. The Post-Presidential Appointment Books series proves whether a writer saw Eisenhower on the date(s) he claimed. An important memorandum on the June 4 and 5 meetings is located in the Lt. Gen. Harold Bull Papers, 1943–1968.

Helpful sources in other manuscripts repositories include the Kenneth S. Davis Collection, Hale Library, Kansas State University; the Chester Wilmot Papers at the National Library of Australia; and the Alan Moorehead Papers, also at the National Library of Australia. Air Vice Marshal James Robb’s account of the June 5 meeting is in the archives of the Royal Air Force Museum in London. I thank all four institutions for their long-distance reference services.

This article benefited by the several, if contradictory, accounts found in the memoirs noted in the text. David Howarth’s D Day: The Sixth of June, 1944 (McGraw-Hill Book Company, Ltd.: New York, 1959) and Cornelius Ryan’s oft-copied, never-surpassed The Longest Day (Simon and Schuster: New York, 1959) are among the best-written narratives of D-day and provide keen observations of the June 5 meeting (Howarth) and Eisenhower’s character (Ryan).

I also want to thank Dr. Timothy Nenninger of the National Archives and Records Administration for his advice and counsel on D-day records.