Broke, But Not Out of Luck

Using Bankruptcy Records for Genealogical Research

Fall 2014, Vol. 46, No. 3

By Jake Ersland

The post–World War I business boom that swept the United States made its way to all parts of the nation, including the heartland—Kansas City, Missouri.

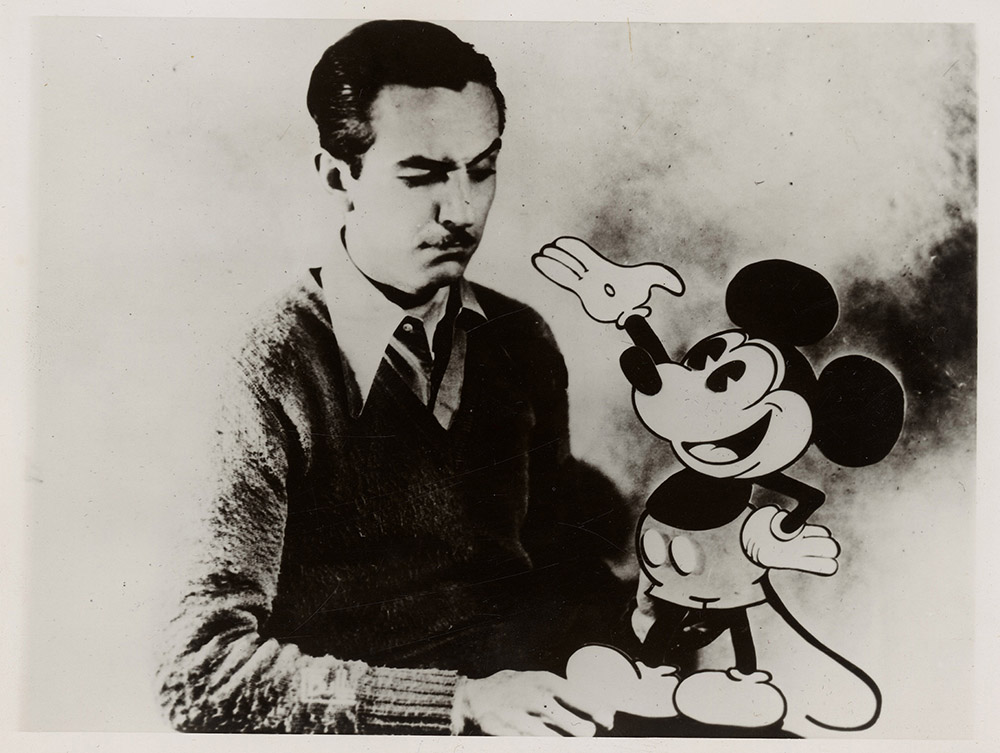

In this city that had been a jumping-off place for westbound explorers was a start-up in the entertainment industry, specializing in the fairly new medium of animated cartoons. Founded in May 1922, Laugh-O-Gram Films, Inc., had an initial capitalization of $15,000.

Despite producing several short films, advertisements, and an information piece for a local dentist, Laugh-O-Gram Films struggled financially. Production costs proved higher than had been anticipated, and new revenues came in only upon completion of projects.

As a result, the company was perpetually behind in meeting its payroll and paying its bills. Salaries for employees were paid only partially, and later than agreed upon. Utility bills at times were completely ignored, and needed supplies were acquired on steadily eroding credit. Things were bad enough at one point that the company’s founder and president could not meet with a potential client because he did not have a decent pair of shoes to wear.

By August 1923, the company folded, and its president left Kansas City to start fresh in California. Bankruptcy proceedings began before the end of 1923. But the founder of Laugh-O-Gram Films, Inc., Walt Disney, who had grown up in the rural Missouri town of Marceline, was already well on his way to bouncing back.

Bankruptcy Records Often Overlooked

A certain negative connotation is generally associated with bankruptcy and the implied failure that accompanies the term. Genealogists are not normally excited to see such information associated with their ancestors. Often family stories allude to past financial difficulties, but rarely is it known whether bankruptcy proceedings occurred. As a result, genealogists often overlook opportunities to use bankruptcy records.

Since 1790, the country has weathered as many as 47 separate recessions or depressions, depending on the economic historian you ask. Reasons for economic downturns include wars, natural disasters, financial bubbles, or faulty foreign or domestic policy. The victims of financial crashes come from all walks of life—rich or poor, highly educated or illiterate, industrious entrepreneur or deadbeat.

The federal government has responded to these downturns in many different ways, including the passage of bankruptcy laws, provided for under Article I, section 8, clause 4 of the U.S. Constitution, which gives Congress the power to legislate for “uniform laws on the subject of bankruptcies.” By 1900, Congress had passed four separate bankruptcy laws—the Bankruptcy Acts of 1800, 1841, 1867, and 1898.

Various Bankruptcy Acts Responded to a Crisis

To understand the potential genealogical use of bankruptcy records, it is helpful to understand what each bankruptcy act covered.

The Bankruptcy Act of 1800 resulted from the Panic of 1797, which was caused by the naval quasi-war with France, deflation from the Bank of England, and a land speculation bubble. This first bankruptcy act covered only merchants and involuntary bankruptcy. The system was rife with corruption and favoritism and was repealed in 1803. As a result, there are not many records of genealogical use from this bankruptcy act.

The Bankruptcy Act of 1841 was a result of the Panic of 1837, which was caused by massive bank failures and a collapse of the cotton market. This act allowed for voluntary bankruptcy, which provided for a discharge of debt. Any individual could file for bankruptcy as well.

Creditors felt that the law was too lenient on debtors, allowing them to discharge too many debts, and the act was repealed in 1843. Though containing more records of genealogical value than the Bankruptcy Act of 1800, there still is not a huge wealth of information available from this bankruptcy act.

The Bankruptcy Act of 1867 was a response to the economic depression caused by the devastation of the Civil War. This act provided for involuntary filings for any individual and created bankruptcy registers to help district court judges handle the large caseloads. Creditors once again thought that debtors were allowed to discharge too many debts, and the act was repealed in 1878. The number of cases generated in the courts greatly increased from the two previous acts, and genealogists have a much higher probability of locating bankruptcy records from this critical period of change and transition in American history.

The Bankruptcy Act of 1898 came about because of the Panic of 1893, which was caused by the failure of the Reading Railroad and a withdrawal of European investment from American markets. Individuals could file for voluntary bankruptcy, and anyone owing at least $1,000 could be adjudged an involuntary bankruptcy. This bankruptcy act remained in place, with a few amendments and adjustments, until 1978. Most cases that genealogists will use are from this bankruptcy act.

Much Information Awaits in Bankruptcy Records

Bankruptcy cases can contain an enormous amount of information. Much of the paperwork consists of standard court orders, setting out dates and actions to be taken. Filings can include the petition for bankruptcy, schedule(s) of debts, lists of names and addresses of creditors, records of amounts due, inventories of real and personal property, notices to creditors, orders of bankruptcy, and final discharges. These records, which make up the bulk of the case file, can contain details that a genealogist cannot find anywhere else.

One potential gold mine of information is the list of creditors. This document lays out the debts of the individual filing for bankruptcy. The identities of those to whom an individual owes money can be very revealing.

For example, a list of creditors from a 1932 bankruptcy case file from Wichita, Kansas, shows that the debtor had racked up a $150 grocery bill at Peerless Grocery in Arkansas City, owed $170 on mortgaged furniture, was indebted to the Ernest Thompson Shell Station for $10 worth of gasoline, and even owed a neighbor for $1.98 worth of kerosene. Perhaps more revealing are the five separate doctor and dental bills owed.

It is possible that physical ailments may have contributed to hard times, both in debts owed, as well as possibly limiting earning abilities. Another interesting note in the file is the debt both for the purchase of, and parts for, a radio. Reviewing this one document reveals much about the individual, providing details on their neighbors, where they shopped, which doctors provided care, and how they spent time at leisure.

Equally telling are lists of property.

The Dust Bowl era brought many farmers to financial ruin as drought conditions and poor farming circumstances led to impossible economic situations.

A look at a farm bankruptcy from western Kansas can reveal a wealth of information on what farm life in the Dust Bowl looked like. All of a farmer’s property is listed, including the amount of seed owned, acres of producing farmland, farm equipment, and farm animals. One list even noted the names of the horses that worked the fields for the family, which included a 7-year-old mare named “Blackie,” a 10-year-old mare named “Avis,” and a 5-year-old mare named “Sis.” It is doubtful there are many other sources for genealogists that provide the names of family animals. Additionally, analysis of equipment owned sheds light on how technologically up to date a farmer was. Information in the case file can also lead researchers to new paths of research, such as the legal description of where property was located.

Statements of All Debts Provides Complete Picture of Business

Case files of businesses that filed for bankruptcy often contain “statements of all debts of bankrupt.” Most businesses that went under were small in nature, often operated by an individual or family. The bankruptcy and subsequent loss of such businesses could alter the course of a family’s life, causing people to uproot and move to look for new opportunities.

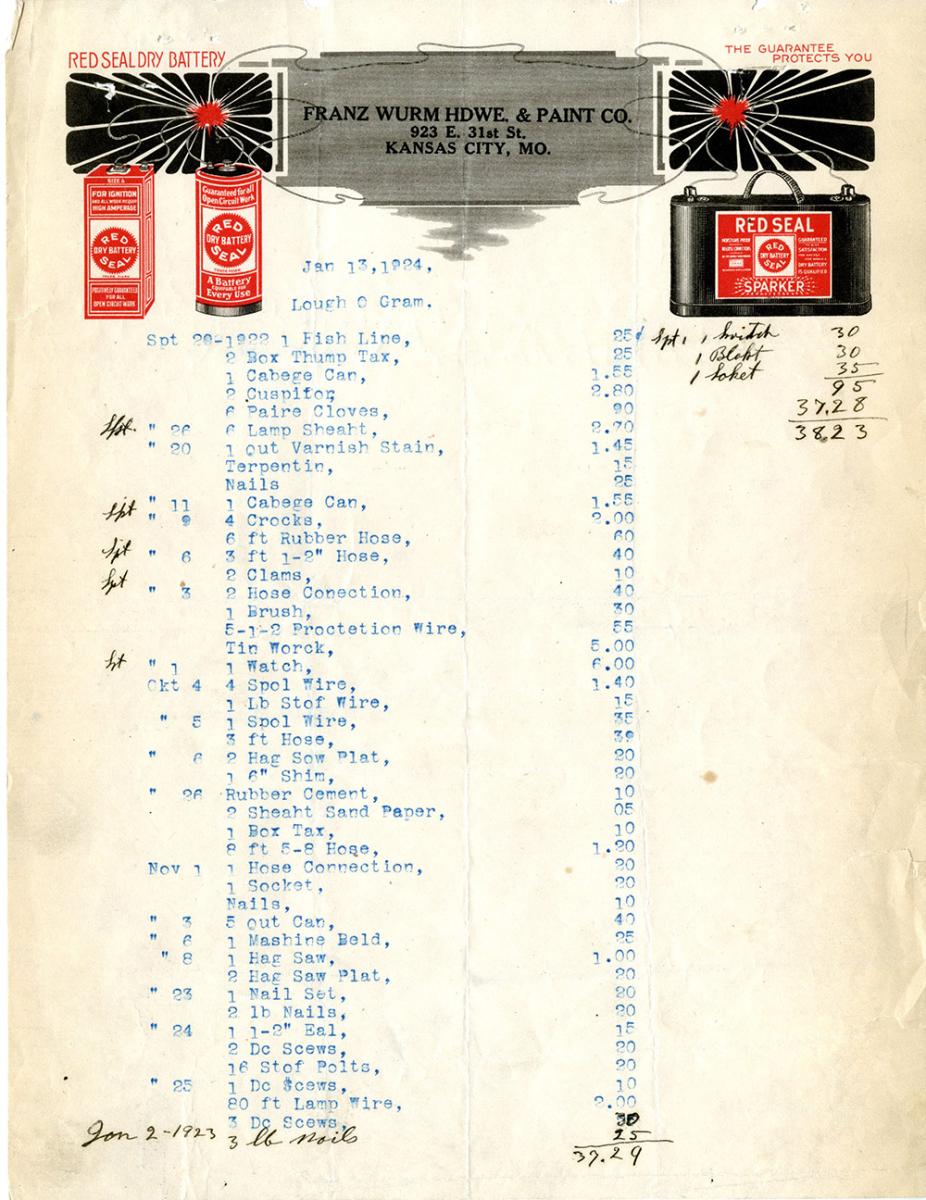

Statements of debt include debts incurred in general operation of the business, from supplies purchased to the furnishings. The statements can also open the door to new avenues of research, such as when money is owed for advertisements purchased in local newspapers. If digital or microfilm copies of the newspapers exist, a researcher can use information found on the statement of debt to locate and view the advertisements produced for an ancestor’s company or business.

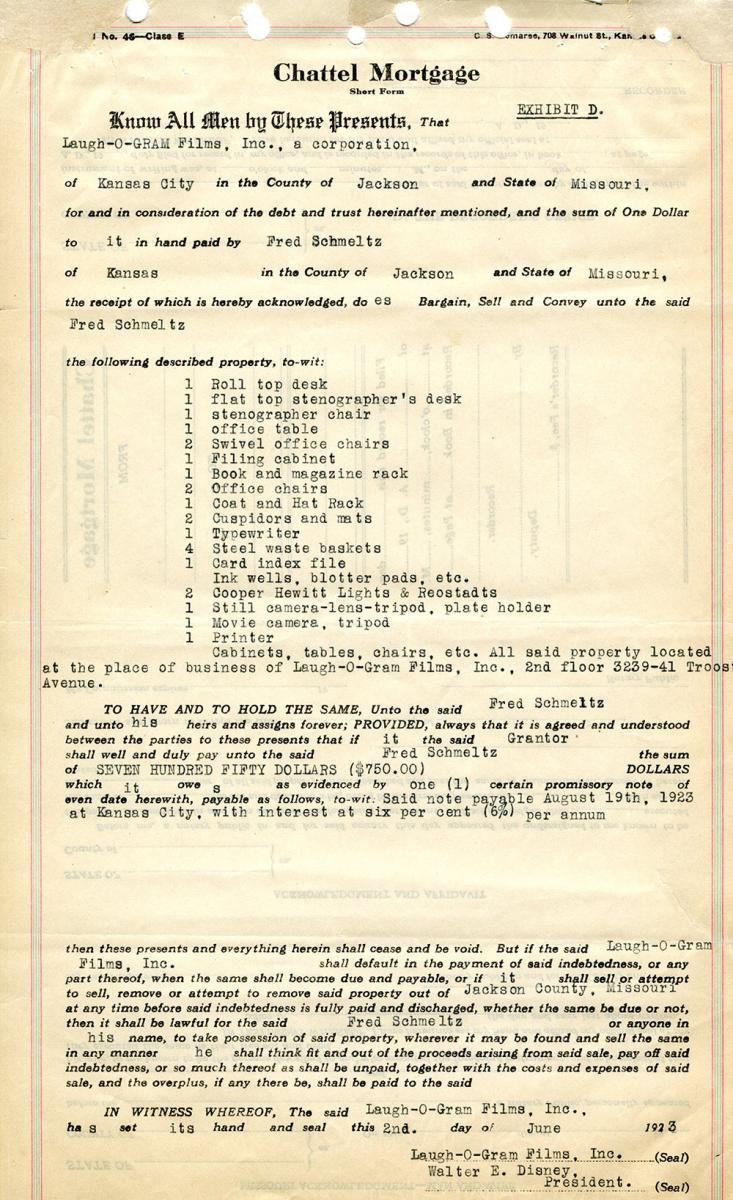

Exhibits filed in bankruptcy cases add depth and understanding to the environment in which a person lived and conducted business.

Often creditor companies would submit inventories on colorful letterhead listing goods purchased on credit. Promissory notes and receipts for goods purchased further document the accumulation of debt and the financial decisions that contributed to the bankruptcy.

Walt Disney’s Laugh-O-Gram bankruptcy included exhibits of each of these types, as well as employee salary schedules, noting what was due on a regular basis, and what was actually paid.

Disney tried to get through financially thin periods by paying employees a percentage of a salary, with the balance to be paid once revenue came in. Unfortunately for Disney, the expected revenue to cover back pay never came in, and employees left the business rather than continue to work for greatly reduced, and uncertain, wages. Such details provide a look into an individual’s decision making and how they tried to weather tough financial times.

Despite the unique information found within the hundreds of thousands of files in the National Archives’ holdings, bankruptcy case files are grossly underused by genealogists. Those looking for new angles to research their family histories should strongly consider bankruptcy case files.

Recently a researcher visited the National Archives at Kansas City to look at an ancestor’s criminal case file. A background discussion revealed that the family had become involved in bootlegging to try to get by financially. A search through the bankruptcy indexes revealed two separate bankruptcy cases for the researcher’s ancestors. The researcher found a wealth of information in the case files, from the legal description of the family’s property, to lists of household possessions, to lists of creditors that happened to include other family members. Researching the bankruptcy case file added an entirely new chapter to the family’s known past.

Federal Records on Bankruptcies in Facilities Around the Country

The federal government has had jurisdiction over every bankruptcy case since 1898, with proceedings held in United States district courts, bankruptcy courts, and territorial courts. To locate a bankruptcy case file, you need to know in which state or territory the proceedings occurred.

The National Archives facility maintaining the federal records for a particular state will have the bankruptcy records from the courts in that location. (A list of National Archives facilities is at the back of the magazine.) Archival coverage greatly varies by court.

Generally, indexes are the first source to consult to locate a specific case. Bankruptcy indexes are not always available, and researchers may need to search through bankruptcy dockets or journal books for cases in a specific date range. Locating a bankruptcy case can be time consuming, but the potential rewards are well worth the effort. Consultation with an archivist to discuss the available resources is often the best course of action, though searches on the Online Public Access catalog on Archives.gov can reveal bankruptcy series for individual courts.

Generally, genealogy research shows paths of lineage, with names and dates of ancestors. Researching records like bankruptcy files allows for a deeper understanding of one’s ancestors: who they were, what they did day to day, what they owned, and even how they entertained themselves.

By showing everything an individual owned, and to whom they owed money, bankruptcy files open the door into the homes of our ancestors. The details revealed in the case files allows the researcher to understand so much more than what a name and a date alone provide. They help a researcher understand why a path guided an ancestor in a particular direction.

Researchers should not let the negative stigma associated with bankruptcy deter them. Failures, both past and present, occur for myriad reasons. Often, individuals fail due to outside circumstances, with little fault of their own.

Even a failure that does rest solely with a person’s poor choices and actions may not indicate that the bankrupt could not have bounced back to bigger and better things.

Walt Disney’s failure in his attempt to start a film company in Kansas City served as a learning experience, which he used to guide him during an incredibly bright career.

In fact, Disney’s most famous creation, Mickey Mouse, was a product of this trying time in his life. Disney claimed to have developed the idea of Mickey from a mouse that lived at his studio at Laugh-O-Gram Films.

The bankruptcy of Laugh-O-Gram Films was not a black mark for Disney, but rather one chapter that describes who he was and where he came from. The same is true for any other bankruptcy case file, waiting for a genealogist to open it up and peer into a family’s past.

Jake Ersland is an archivist at the National Archives at Kansas City. He received both his bachelors and masters degrees in history from Pittsburg State University. He works extensively with records of the U.S. District Courts and has given numerous presentations on using court records for genealogical research.

Note on Sources

Details on Walt Disney’s time at Laugh-O-Gram Film Company, Inc., came from Timothy Susanin’s Walt Before Mickey: Disney’s Early Years, 1919–1928 (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2011). Other sources consulted for historical information on federal court history included Erwin Surrency’s History of the Federal Courts (New York: Oceana Publications, Inc., 1987) and David Skeel’s Debt’s Dominion: A History of Bankruptcy Law in America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001) for details on federal bankruptcy law.

All bankruptcy records discussed in the article are part of the holdings of the National Archives at Kansas City in Record Group 21, Records of District Courts of the United States. Walt Disney’s Laugh-O-Gram Film Company, Inc., bankruptcy is from the records of the Western Division (Kansas City), of the Western District of Missouri, Bankruptcy Act of 1898 Case Files, 1898–1950 (National Archives Identifier 572819). Both the list of creditors and lists of property came from cases from the series Bankruptcy Act of 1898 Case File, 1898–1963 (National Archives Identifier 572982) from the Wichita Division of the District of Kansas.