Searching for the Seventies

The DOCUMERICA Photography Project

Spring 2013, Vol. 45, No. 1

By Bruce I. Bustard

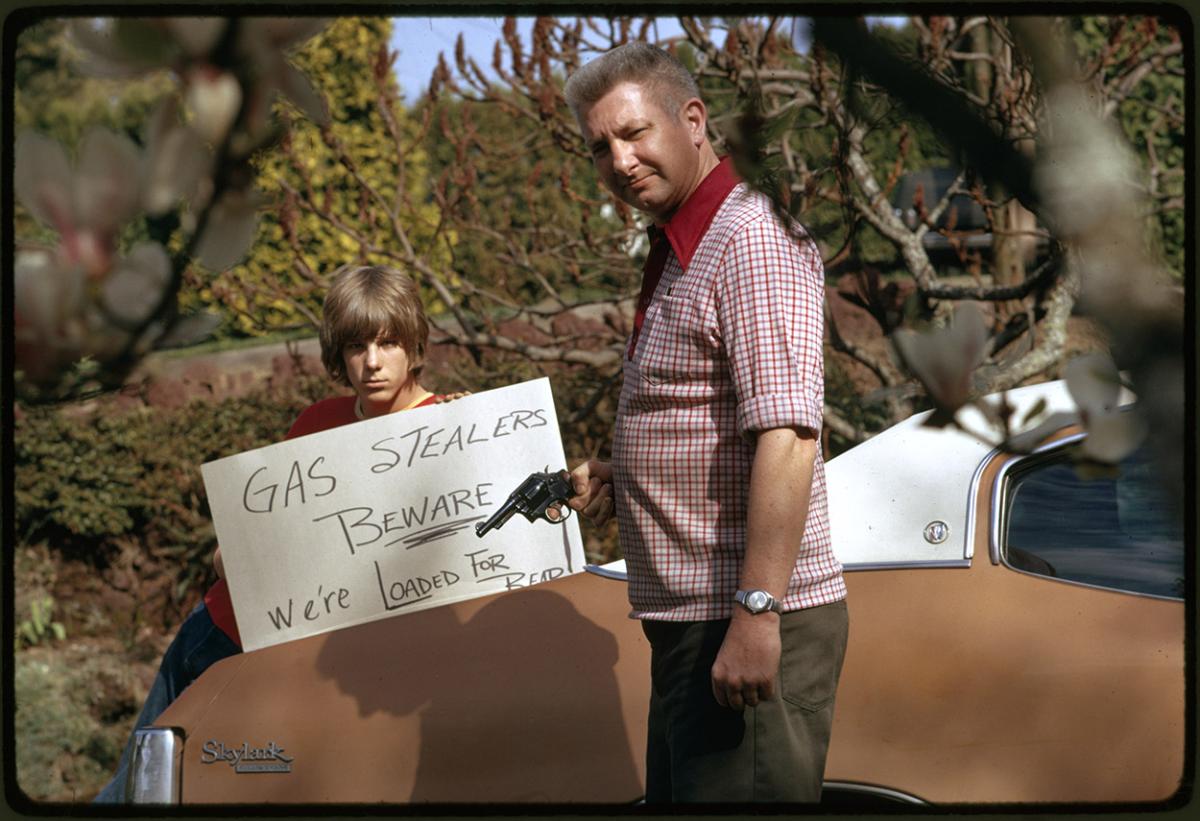

Bad fashion, odd fads, and disco dance music sum up the 1970s for many Americans. We contrast those years to the politically committed 1960s civil rights triumphs, antiwar protests, Great Society reforms, and New Left radicalism. They seem a poor relation to the economically booming 1980s Republican resurgence, yuppies, tax cuts, and leveraged buyouts.

The decade of the seventies is remembered as a time of soaring inflation, political corruption, and loss of prestige around the world. It was an era of political and economic drift—the self indulgent “me decade.”

But the1970s were much more than leisure suits, streaking, and disco. Their importance goes beyond high gas prices, Watergate, and Vietnam. During the seventies, profound changes took root in our politics, society, and economy.

A new National Archives exhibition, “Searching for the Seventies: The DOCUMERICA Photography Project,” invites visitors to take a fresh look at the 1970s through the lens of a federal photography project called Project DOCUMERICA.

Created by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1971, DOCUMERICA was born out of the decade’s environmental awakening and produced striking photographs of many of that era’s environmental problems and achievements. As you might expect, the photographers hired by the EPA took thousands of color photographs depicting pollution, waste, and blight, but they were given the freedom to capture the era’s trends, fashions, and cultural shifts. The result is an amazing archive and a fascinating portrait of America from 1972 to 1977.

What Was DOCUMERICA and How Did It Work?

DOCUMERICA was the brainchild of Gifford “Giff” Hampshire, a photo editor and federal government employee who had worked for National Geographic. After he joined the EPA’s Office of Public Affairs, Hampshire convinced EPA Administrator William Ruckelshaus to support a photography project that would document the 1970s environmental crisis in much the same way the Farm Security Administration photography project had documented the Great Depression of the 1930s.

In November 1971, Ruckelshaus and Hampshire introduced DOCUMERICA to the public and the media. The project initially employed about 50 photographers to “pictorially document the environmental movement in America in this decade.” Its photographs would establish “a visual baseline” of 1970s environmental images from which improvements could be measured.

For example, DOCUMERICA photographers might “record . . . current air pollution problems” and later re-photograph the same locations to chart progress. Other subjects would include water pollution, solid waste management, pesticide control, noise pollution, and radiation reduction. The photographs would demonstrate the “impact of the environmental problem,” tally the social and economic costs of environmental change, document “the environmental movement itself,” and more broadly, “depict Americans ‘doing their environmental thing.’”

But Hampshire encouraged his photographers to look beyond pollution and other problems, and seek out what he called “the human connection” to these issues.

“Where you see people,” he told them, “there’s an environmental element to which they are connected. The great Documerica pictures will show the connection and what it means.”

The Photographers Pick Their Subjects

Over six years, Hampshire hired about 70 photographers who would complete 115 assignments covering all 50 states. Assignments varied. They could be as narrow as Gene Daniels’s effort to photograph “fly fishermen for conservation” or as general as Frank Alexsandrowicz’s to record “the environmental problems of Cleveland, Ohio.”

A few assignments, such as Bruce McAllister’s to photograph the EPA’s clean-up of a Utah pond, or Bill Shrout’s visit to an EPA laboratory, were directly tied to the agency’s mission.

Others came from the photographer’s own interests.

Lyntha and Terry Eiler’s work dealt with northern Arizona, where the couple lived, and centered on “polluters on Arizona Indian Reservations.” Yoichi Okamoto received an assignment to explore whether suburbia near his home in Washington, D.C., was “the American dream or a gateway to frustration.” Flip Schulke (and later some of his photography students) returned repeatedly to New Ulm, Minnesota, where he chronicled the environmental issues in his hometown.

Many photographs in the exhibit brilliantly captured diverse aspects of American society in the seventies. Tom Hubbard saw Cincinnati’s Fountain Square as a “public square that works for the city and its people,” and many of his street photographs playfully chronicled 1970s fashion and style. Charles O’Rear’s photograph of a young hitchhiker drifting along Arizona’s Route 66 with his dog, “Tripper,” captured the 1970s youth culture and its challenges to traditional ideas about dress, masculinity, and work.

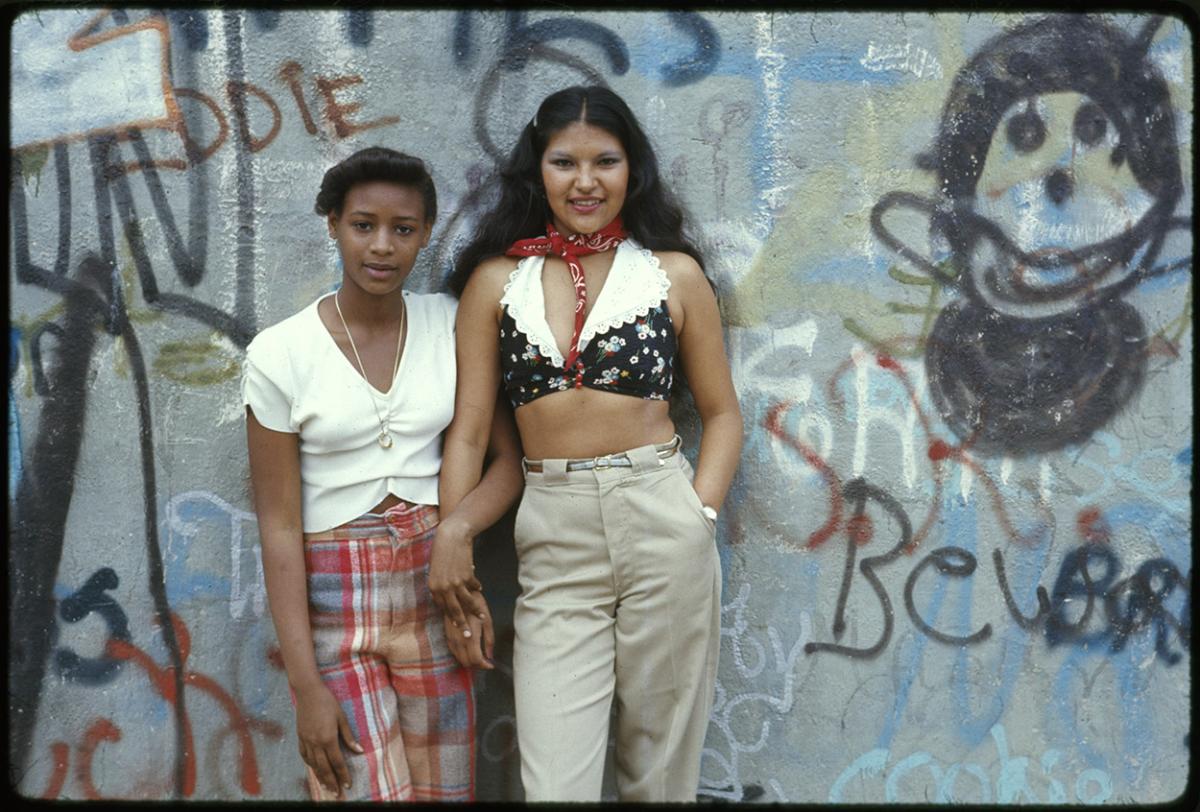

Other photographers also did an admirable job picturing the nation’s growing cultural diversity, as, for example, Bill Gillette’s series of photographs on migrant workers, Terry and Lyntha Eiler’s shots of Native Americans, and Flip Schulke’s study of retirees in Miami, Florida. John H. White saw his extensive coverage of Chicago’s African American community as a means of creating a historical record of that community and also as a way of allowing the viewer to enter “into the lives of people you might otherwise never meet.”

One of Danny Lyon’s assignments emphasized the contrast among “Blacks, latins, and poor whites” living in Brooklyn, New York, and “main stream [sic] America’s gas station expressways shopping centers and tract homes.” And a Schulke portrait pictured an interracial couple with their daughter enjoying July 4th fireworks in Sleepy Eye, Minnesota.''

Not Just Pollution But a Slice of the Seventies

Because DOCUMERICA was run by the EPA, many assume that its photographers photographed only dead fish, smog, and polluted rivers During its lifetime, the project failed to capture America’s imagination, but EPA’s creation of DOCUMERICA’s photographic file and its preservation in the National Archives will give future generations a view of the 1970s that is broad and deep. DOCUMERICA’s archive moves us farther from the stereotype of the 1970s as a time when “it seemed like nothing happened,” and allows us to glimpse the nascent problems, issues, and changes that would shape our future.

“Searching for the Seventies” is organized thematically. Each of the exhibition’s three sections takes its title from songs popular during the 1970s. “Ball of Confusion” focuses on the issues and problems that were on the minds of Americans in the seventies.

Everybody Is a Star” showcases DOCUMERICA’s portraits to emphasize how we expressed ourselves more vibrantly than in the buttoned-up ’50s and early ’60s. “Pave Paradise” shows how DOCUMERICA photographers viewed the American landscape.

Four smaller, “On Assignment” sections feature the work of DOCUMERICA photographers Jack Corn, John H. White, Lyntha Eiler, and Tom Hubbard. DOCUMERICA textual documents—caption sheets, correspondence, photographer’s notebooks, and magazine articles—allow us to study in depth the project, its photographs, and its photographers.

“Searching for the Seventies” will be on display in the Lawrence F. O’Brien Gallery at the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C., from March 8 through September 8, 2013.

Bruce I. Bustard is senior curator at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. He was curator for “Searching for the Seventies” and for “Attachments: Faces and Stories from America’s Gates” in 2012.