Nixon on the Home Front

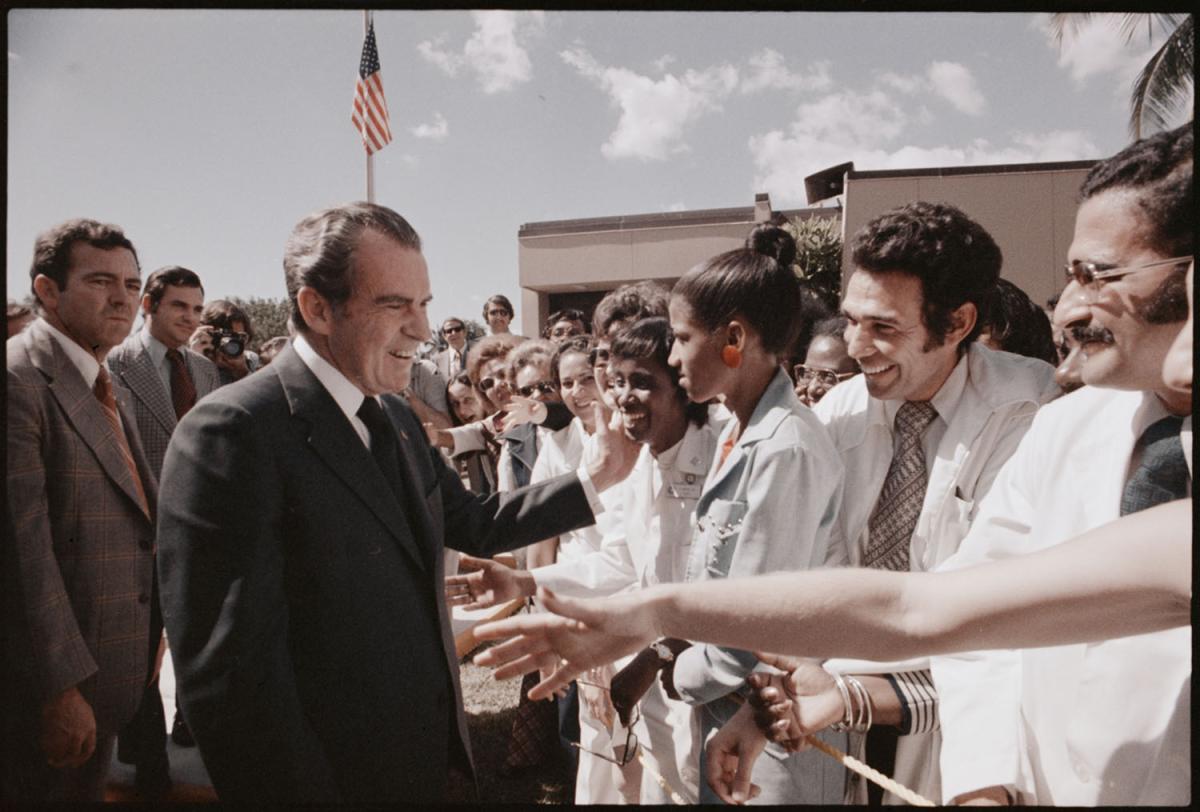

The 37th President’s Domestic Policies Increased the Reach of Government

Winter 2012, Vol. 44, No. 4

When most people think of Richard Nixon’s presidency, two subjects come to mind. One is foreign policy—the Vietnam War, détente with the Soviet Union, and the opening to China. The other is Watergate—the break-in, the tapes, and the resignation.

Rarely examined by historians or journalists are the policies, programs, and legislative victories that make up the domestic legacy of the Nixon administration.

The 37th President focused much of his own attention on foreign policy. According to Henry Kissinger, his top national security adviser, “No American president possessed a greater knowledge of international affairs. None except Theodore Roosevelt had traveled as much abroad or attempted with such genuine interest to understand the views of other leaders.”

This interest in foreign policy, however, obscured his efforts in the domestic policy realm, where he advocated, approved, helped execute, or acquiesced in a number of sweeping domestic policy initiatives that have left a large mark on the lives of Americans and the economy they live and work in today.

Sweeping environmental laws and regulations reach into nearly every aspect of American life. Federal education rules have resulted in equal funding for boys’ and girls’ sports. New laws and regulations changed the face, and gender, of America’s workforce. And two of his proposals that Congress rejected then—welfare reform and health care mandates—have finally made it into the law books.

This year marks the centennial of Nixon’s birth in Whittier, California. He attended Whittier College there, and went on to Duke University School of Law. After serving in the Navy in World War II, Nixon was a major player in postwar U.S. politics as a member of the House and Senate from California, Vice President under Dwight D. Eisenhower, and President—and an active former President until his death in 1994 at age 81.

Elected President at the end of the 1960s, Nixon faced a nation in turmoil. Vietnam War protests—in Congress and in the streets—civil rights groups, an increasingly vocal environmental movement, and more and more special-interest, single-issue groups were demanding specific actions on domestic and foreign policies. And the nation was still reeling from two assassinations in 1968: Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert F. Kennedy.

He also faced an economy hobbled by the massive spending for the Vietnam War and for President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society programs. Although the unemployment rate was low, inflation was high. Nixon’s efforts to bring down inflation were not successful, despite his imposition of wage and price controls.

Nixon did not make a major effort to scale back or dismantle Johnson’s Great Society programs. In fact, he made a number of proposals, and carried out a number of laws passed by the Democratic Congress, that made it seem like he was continuing the Great Society.

Herbert Stein, who was chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers for Presidents Nixon and Gerald R. Ford, has been quoted in numerous places as saying, “Probably more new regulation was imposed on the economy during the Nixon administration than in any other presidency since the New Deal."

Johnson’s massive Great Society was a collection of government programs as sweeping as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. It included reforms to end poverty and racial discrimination in all aspects of American life as well as big spending programs in education, urban affairs, transportation, and Medicare.

Nixon’s approach to government was that of centrist Republicans, who were conservatives but still saw a role for government in American life, albeit not as large as Democrats would have it.

On two issues, Nixon may have been ahead of his time. In 1971, he proposed a health care plan that would provide insurance for low-income families and would require employers to provide health care for all employees. Democrats in Congress, led by Senator Edward Kennedy, wanted a more sweeping bill. A compromise between the President and Kennedy, whom Nixon believed might be his 1972 opponent, never happened. It took nearly four decades for significant changes in the nation’s health care system to be enacted.

Nixon also proposed welfare reform. His plan, developed by a group of advisers led by Daniel Patrick Moynihan, was a program of family allowances, but it was defeated in the Senate. More than two decades later, Moynihan himself played an important role opposing welfare reform, as a senator from New York in 1996, between a Republican Congress and a Democratic President.

Despite these and other setbacks, the Nixon administration presided over the creation of a variety of programs and policies that are now part of everyday life. Most scholars say that on domestic issues, Nixon was pragmatic. As Nixon scholar Dean J. Kotlowski put it in A Companion to Richard M. Nixon:

"A Republican President, elected in part because of backlash against the Great Society, presided over a major expansion of the powers of the federal government in areas of environmental protection and national parks, occupational safety and old-age security, mass transit, and aid to cities."

Reorganizing the Government to Police the Environment

Only eight days into his presidency in 1969, Nixon was confronted with what became for many a galvanizing environmental tragedy—an oil spill off the coast of Santa Barbara, California. This event, along with others, such as the fire on the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland, increased attention on environmental issues. What had at best been a minor issue during the 1968 presidential campaign by 1970 became a major political issue, perhaps best symbolized by the first Earth Day celebration on April 22, 1970.

On January 1, 1970, the President signed the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, which sought to establish a national environmental policy and created a Council on Environmental Quality. In December 1970, he signed one of the most important pieces of environmental legislation in U.S. history—the Clean Air Act of 1970, which called for drastic reductions in harmful emission from automobiles and other sources of air pollution.

To enforce the Clean Air Act and other environmental legislation, he signed an executive order to reorganize the executive branch and establish the Environmental Protection Agency. Environmental regulation, like many functions of the federal government, had grown piecemeal over time, resulting in authority spread among many parts of the government.

The new EPA inherited some of the powers of agencies such as the Federal Water Quality Administration, the National Air Pollution Control Administration, the Bureau of Solid Waste Management, the Bureau of Radiological Health, the Environmental Control Administration, the Food and Drug Administration, the Atomic Energy Commission, and the Agricultural Research Service.

Although Nixon remained committed to environmental issues, his support was later tempered by concerns over the economic ramification of regulation and the direction of the environmental movement, which in turn was critical of the administration, most notably for its support of the Alaskan Oil Pipeline project.

On January 7, 1972, in a conversation recorded in the Oval Office, Nixon spoke to EPA Administrator Russell Train, giving his views

"The environment thing must not be allowed to become a fad of the elitist. A fad of the ecological, etc. You know what I mean: a fad of the upper-middle class. . . . The environment thing, to really mean something to this country, has got to reach down to that blue-collar guy and the rest and so forth. To the fellow perhaps who does not quite comprehend as good as the upper-class what it’s all about. . . . And it isn’t going to mean anything to him unless he gets the chance to use the facilities."

Today the EPA, with cabinet status, is one of the most powerful government agencies. Many of its policies and the regulations derived from them drew strong opposition in the business community, most notably the automobile manufacturers who argued that the cost of reducing emissions from new cars would add significantly to their final price. Four automakers sued the EPA to extend the deadlines, aided by the oil companies who resisted the phase-out of leaded gasoline.

The Civil Rights Movement and School Desegregation

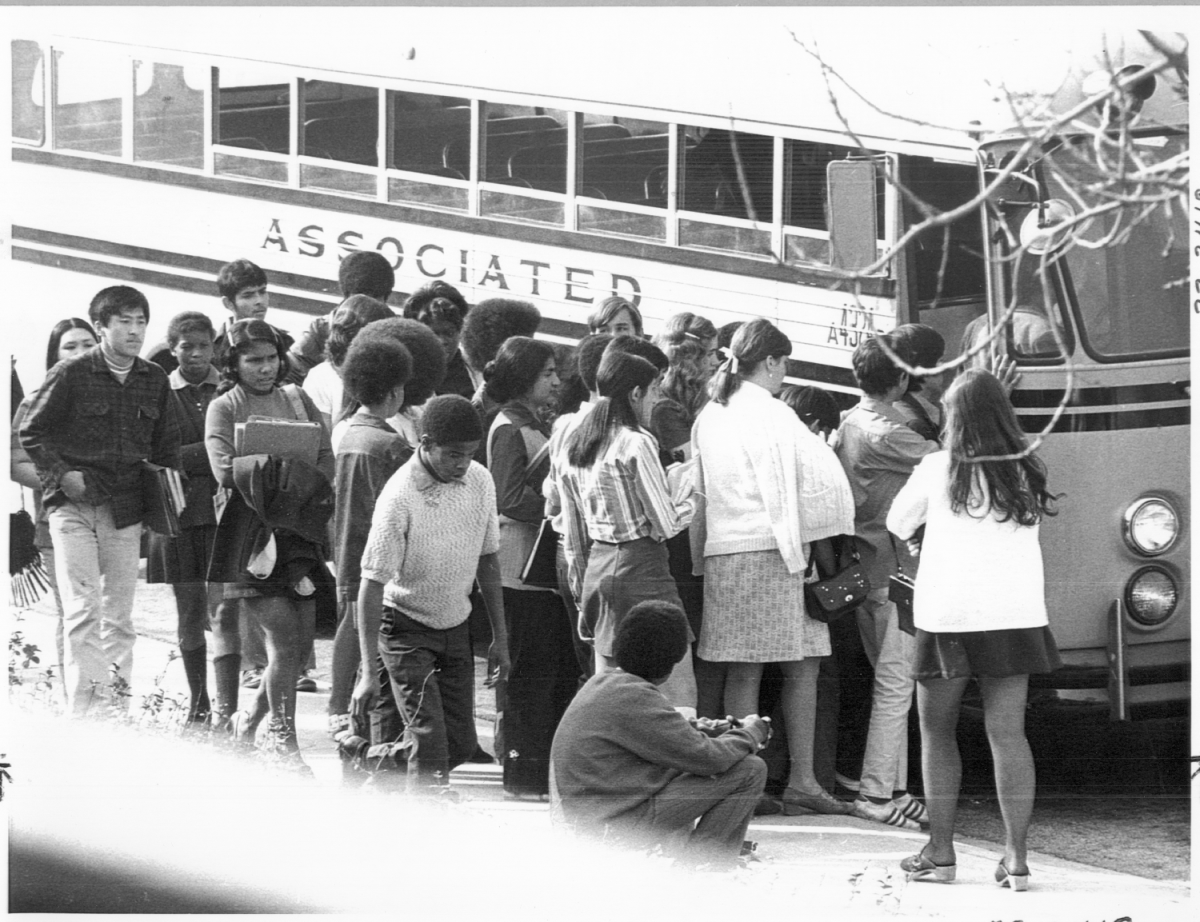

Some of the fiercest and earliest of the battles of the civil rights movement took place on school grounds, where the inherent inequality of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1896 “separate but equal” policy was painfully apparent. Across the country, and especially in the South, black schools were drastically inferior to their white counterparts.

A solid education was then, as it is now, a critical key to social mobility. Proponents of integrated schools, like all citizens, wanted the next generation of children to have a better life than their own.

The Supreme Court’s historic 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education overturned the 1896 ruling and changed the political landscape.

The first large-scale integration of public schools occurred during the Nixon administration. In a 1970 North Carolina case, Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, the Supreme Court unanimously approved the use of busing as a legal means to desegregate schools. In the early 1970s, tensions over court-ordered school desegregation increased in northern cities like Boston and Detroit. Although he opposed busing to achieve desegregation, Nixon enforced the court orders to do so.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 ended the Jim Crow laws in the South that were responsible for some of the most striking images of segregation, such as separate water fountains and whites-only lunch counters. It also gave the Justice Department the teeth it needed to enforce school desegregation. By the time Nixon ran for President in 1968, the number of African American children in integrated schools had increased to 10 percent.

Yet, despite Nixon’s support for civil rights—from 1957 to 1968 he endorsed every major civil rights law—he knew that he needed to win the support of segregationists in the South to win the election. Both on the campaign trail and in his presidency, Nixon forged a centrist position.

This tactic sometimes caused confusion.

“Nixon revealed no real personal desire to roll back the fundamental accomplishments of the civil rights movement,” writes southern historian James C. Cobb, “[but] from a political standpoint it clearly made sense for him to give Southern whites the impression that he [was] trying to do just that.” Indeed, one of the key challenges for scholars trying to understand Nixon’s policy is disentangling his “liberal deeds from his conservative words” while giving him due credit for his role in overseeing the peaceful desegregation of schools after decades of violence.

For Nixon, the issue was complex. On January 28, 1972, Nixon outlined his position on busing and freedom of choice in a memorandum to John Ehrlichman.

"I begin with the proposition that freedom in choice in housing, education and jobs must be the right of every American. . . . Legally segregated education, legally segregated housing, legal obstructions to equal employment must be totally removed. . . . On the other hand, I am convinced that while legal segregation is totally wrong that forced integration of housing or education is just as wrong. . . .

"Brown v. Board of Education in effect held that legally segregated education was inferior education. Once the legal barriers which caused segregation were removed and the segregation continued the philosophy of Brown would be that any segregated education, whether it was because of law or because of fact is inferior. That is why I see the courts eventually reaching the conclusion that de facto segregation must also be made legally unacceptable.

"In any event, I believe that there may be some doubt as to the validity of the Brown philosophy that integrating education will pull the Blacks up and not pull down the Whites. But while there may be some doubt as to whether segregated education is inferior there is no doubt whatsoever on another point—that education requiring excessive transportation for students is definitely inferior. I come down hard and unequivocally against busing for the purpose of racial balance."

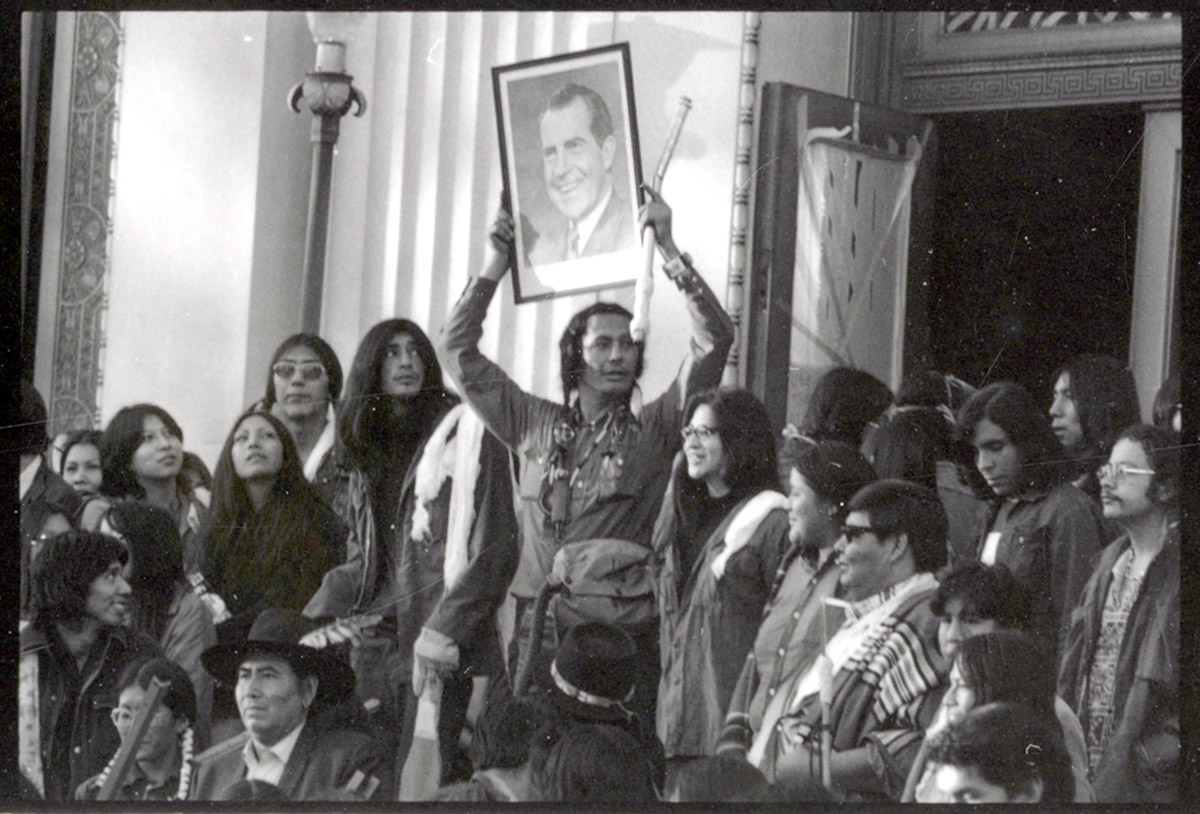

Nixon’s Special Interest in Native Americans

Richard Nixon believed past federal policies had treated Native Americans unjustly, a belief that grew out of his experiences at Whittier College with his football coach, Wallace “Chief” Newman. Nixon once recalled:

"I think that I admired him more and learned more from him than from any man I have ever known aside from my father. Newman was an American Indian, and tremendously proud of his heritage. . . . He inspired in us the idea that if we worked hard enough and played hard enough, we could beat anyone."

In a Special Message to the Congress, dated July 8, 1970, Nixon made it clear that he sympathized with the plight of Native Americans:

"On virtually every scale of measurement—employment, income, education, health—the condition of the Indian people ranks at the bottom. This condition is the heritage of centuries of injustice. From the time of their first contact with European settlers, the American Indians have been oppressed and brutalized, deprived of their ances-tral lands and denied the opportunity to control their own destiny. Even the Federal programs which are intended to meet their needs have frequently proven to be ineffective and demeaning.

It is long past time that the Indian policies of the Federal government began to recognize and build upon the capacities and insights of the Indian people. Both as a matter of justice and as a matter of enlightened social policy, we must begin to act on the basis of what the Indians themselves have long been telling us. The time has come to break decisively with the past and to create the conditions for a new era in which the Indian future is determined by Indian acts and Indian decisions."

This message served as an outline for proposals by the administration to Congress to address Native American policy concerns. Top among these was the long-standing federal policy of forced termination. This policy sought to sever the relationship between the federal government and tribes, ending the special status given to Native Americans, including those guaranteed by treaty. The policy’s effect was in fact to destroy the tribal system by forcing the division of property among the tribal members and ending a formal relationship with the federal government. Nixon rejected this in no uncertain terms, promoting instead increased tribal autonomy.

Nixon also sought to expand tribes’ rights to control and operate federal programs, to increase funding for Indian health care, and to expand help for urban Indians to promote Native America economic development through expanded loans and loan guarantees.

Much of this agenda was defeated by conservative opponents in Congress, but the return of the sacred lands near Blue Lake was successful.

Blue Lake, located in north central New Mexico, is a site sacred to the Taos Pueblo tribe. In 1906 the tribe was stripped of ownership of the land when President Theodore Roosevelt included it in the Taos Forest Reserve. This started a decades-long fight by the tribe to regain its sacred land.

In 1951 the tribe took the issue to the Indian Claims Commission, which ruled that the government “took said lands from petitioner without compensation.” While the tribe was willing to negotiate a financial settlement for some of the land in question, they insisted on the return of 48,000 acres of sacred land. Nixon was able to work with members of Congress to overcome opponents and return the land to the tribe.

Nixon and Moynihan on Welfare Reform

Daniel Patrick Moynihan seemed an unlikely candidate for a senior position in the Nixon administration. In 1960, he was a delegate for John F. Kennedy during at Democratic National Convention and later was assistant secretary of labor in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. When Nixon took office, he headed the Joint Center for Urban Studies at Harvard University.

As a senior adviser on domestic policies, Moynihan brought a certain energy to his position, working closely with President Nixon on a variety of issues. Perhaps the most interesting was an ill-fated proposal to reform the welfare system, which became known as the Family Assistance Plan (FAP).

The fundamental aspect of the FAP was to establish a minimum payment to families with dependent children throughout the nation. This payment amounted to $1,600 per year for a family of four (about $9,100 in today’s dollars).

The fundamental change in policy was to create a system that extended payments to what might be termed the working poor. It was calculated to encourage those on welfare to develop job skills and to support those who did not earn enough to survive to keep their jobs rather than quit in order to qualify for welfare.

Nixon proceeded with the Family Assistance Plan, which most of his economic advisers opposed and whose passage was doubtful. Conservatives in his own party opposed any expansion of the welfare system. Whether it was for political or personal reasons, it is clear that Nixon liked bold proposals that caught his critics off guard.

The plan passed the House of Representatives, but it died in the Senate. Conservatives opposed the plan based on the expansion of government payments, and some liberals were unwilling to fully support the plan in part because it was coming from a Republican President.

The Philadelphia Plan and Equal Opportunity

The Nixon administration also took on discrimination in the workplace.

One of the industries targeted for action was construction, where discrimination was painfully evident. African Americans were often excluded from union membership, something required for working in construction. Although discrimination in federal hiring had been outlawed years earlier, by the end of the 1960s, it still barred many people from good jobs.

In 1969 the Department of Labor announced what became known as the Philadelphia Plan, to combat discrimination in the Philadelphia construction industry. This plan set targets for construction firms holding federal contracts, requiring them to hire African American workers.

The Philadelphia Plan was followed by others—the New York Plan, the Atlanta Plan, the Chicago Plan—all devised to end discriminatory hiring in the construction industry. Both labor unions and some in the Republican Party objected to the plans. Some Republicans feared that the employment targets were quotas, which Nixon disputed.

Labor union charged government interference and political grandstanding. Whatever the case, the plans furthered Nixon’s belief that economic advancement was a tonic for discrimination.

Appointing More Women to Government Offices

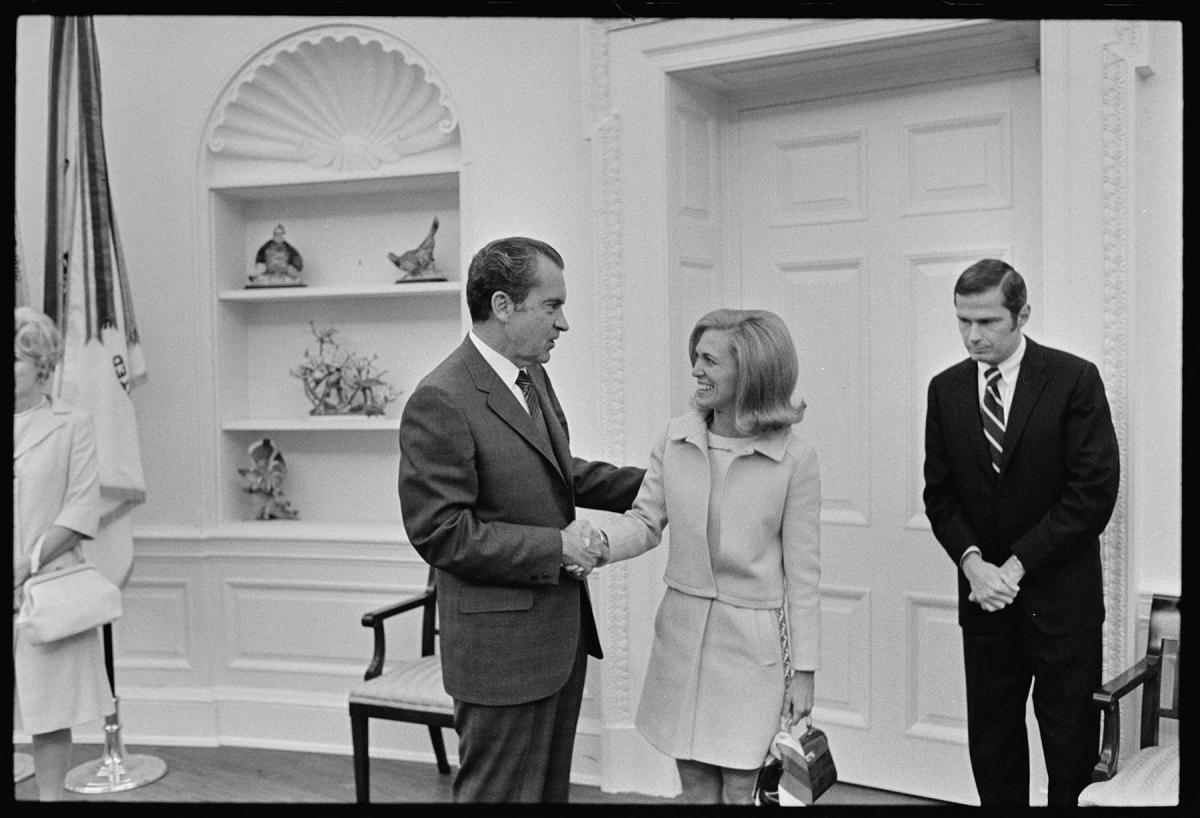

Nixon also sought to appoint more women to key government positions. In April 1971 he required federal agencies to develop plans to hire more women in top positions. At the same time he made two important appointments. First he appointed Jayne Baker Spain as commissioner of the Civil Service Commission, charging her with finding ways to expand women’s role in government. Most importantly, he made Barbara Hackman Franklin a staff assistant in the White House Personnel Operations office.

Franklin was given responsibility to recruit women for high-level policy-making positions. Working with Fred Malek, the head of White House Personnel Operations, she set about working with agencies to create and monitor action plans for hiring women. With the help of Franklin and support from the White House, women began to make small but significant advances.

Another woman Nixon tapped was Elizabeth Hanford, who was a deputy assistant to the President from 1969 to 1973, then a member of the Federal Trade Commission. (She later married Senator Robert Dole, the 1996 GOP presidential candidate, and served as North Carolina’s first female senator.)

In 1972 women broke into tradition-ally male-only occupations, becoming FBI agents, sky marshals, Secret Service agents, and narcotics agents. President Nixon nominated the first six women to the rank of general in the armed forces and the first woman as rear admiral in the Navy. He also appointed the first woman to serve on the Council of Economic Advisers—Marina von Neumann Whitman.

Nixon Signs Legislation Affecting Education, Jobs

Another area in which the Nixon had a tremendous impact on women’s rights was the signing the Higher Education Act of 1972.

“No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance,” read Title IX of the act.

While the overarching intent of this part of the act was to eliminate gender discrimination in a full range of college activities, its most prominent long-term impact has been to expand women’s enrollment in college and to greatly increase women’s sports programs.

Starting with the Nixon administration and finalized under President Gerald R. Ford, the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) crafted regulations to implement Title IX. Many people and institutions, including the NCAA, opposed the act because they feared it would destroy revenue-producing men’s athletic programs, such as football.

The regulations that HEW finally crafted did not go as far as some supporters wanted—in part because they did not mandate equal funding for men’s and women’s sports—but they did lead to an enormous expansion of women’s athletic programs.

Title IX ultimately had much broader implications by outlawing discrimination in ad-missions. In 1970, of the roughly 5.8 million people enrolled full-time in two- and four-year college programs, men constituted 60 percent. By 2010 women’s enrollments actually exceeded men’s, 55 percent to 45 percent.

Finally, Nixon signed the Equal Employment Act of 1972, marking a benchmark in government enforcement of civil rights. The act extended to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission the ability to sue employers and educational institutions for alleged hiring discrimination based on race or gender.

Before the passage of the 1972 legislation, the EEOC relied on persuasion as a means of addressing discrimination. Opponents of the 1972 act wanted to keep the status quo, while many advocates of the act wanted to endow the EEOC with the ability to impose cease-and-desist orders on employers.

President Nixon believed judicial review was the appropriate means of resolving alleged discrimination. The administration pushed to expand the commission’s powers so that it could bring lawsuits on behalf of the government to address discrimination.

This strategy, coupled with a large increase in budget, supported by the President, resulted in a sea change in hiring practices. The EEOC targeted large employers as examples. In 1973 the EEOC came to a much-publicized consent agreement with the nation’s largest employer, AT&T, which resulted in payments and pay raises to thousands of female and minority employees for past job discrimination.

The agreement also called for AT&T to set hiring goals for women and minorities. In 1974 the EEOC and the Justice Department sued the nation’s nine largest steel manufacturers, which employed more than 350,000 people. This case also resulted in consent decree that provided $31 million in back pay to more than 40,000 employees.

High-profile cases such as these sent a message to American businesses that they risked government initiated lawsuits if they did not comply with antidiscrimination laws.

Nixon Changes Strategy in the Space Program

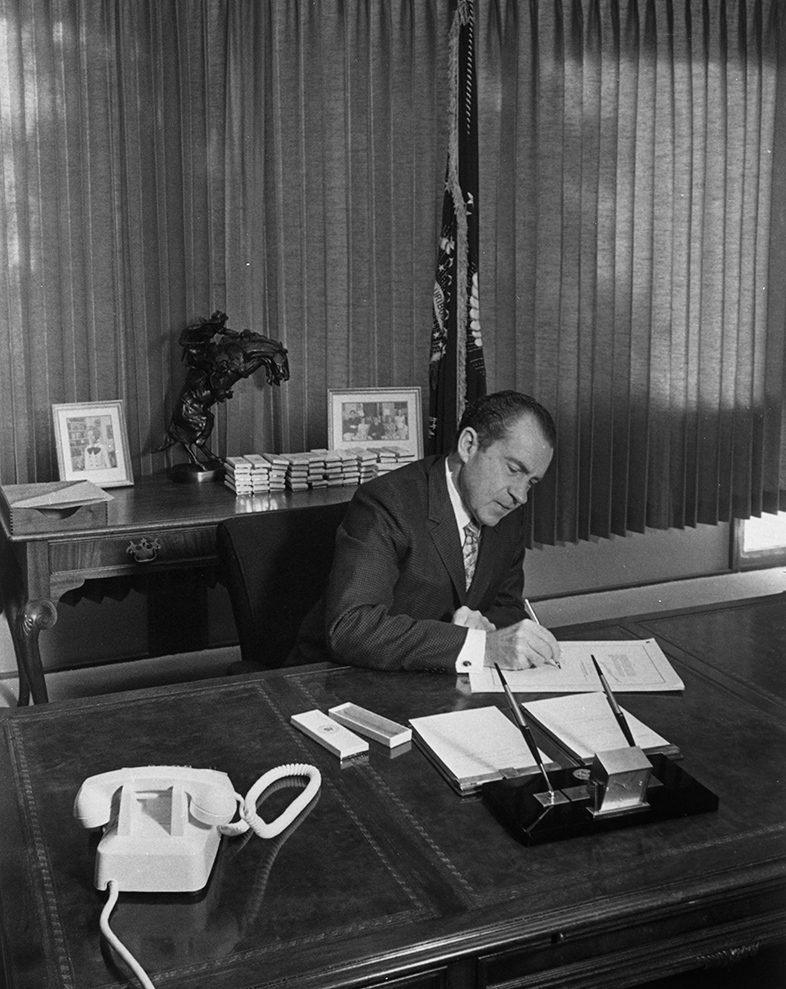

When Neil Armstrong made his first historic step on the face of the moon, President Nixon, watching in the Oval Office, ex-claimed “Hooray” and clapped.

Later, Nixon took a telephone call from the astronauts on the moon. The President shared many Americans’ fascination with the Apollo program. Before Nixon left office, he would witness five additional moon landings.

The Apollo program was proposed by President John F. Kennedy, and much of the heavy lifting was done during the Lyndon B. Johnson administration. The project was undertaken against the backdrop of the Cold War. The “Space Race” pitted American and Russian scientists against each other to be the first to reach milestones in space, with a manned flight to the moon being the greatest objective.

By July 1969, when the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) launched Apollo 11 and American astronauts walked on the moon for the first time, it became clear that America had won the space race. Five more missions reached the moon by 1974, becoming almost a commonplace event for some Americans.

Even though the 1969 moon landings marked a monumental achievement, the American public quickly lost interest in the moon landings. As early as 1969, Nixon started to set the stage for dramatic reshaping of the American space program when he asked Vice President Spiro Agnew to chair a Space Task Group charged with looking at the future of the American space program. That group produced a report that presented three options. The first two involved sending men to Mars by the mid-1980s or later. The final plan called for only a space station and a space shuttle, costing an estimated $5 billion a year.

In 1970, with the public no longer seeing the space race as a national imperative and increasingly concerned about other domestic issues, President Nixon reoriented the U.S. space program. In a “Statement about the Future of the United States Space Program,” he said:

"Having completed that long stride into the future which has been our objective for the past decade, we must now define new goals which make sense for the seventies. . . . But we must also recognize that many critical problems here on this planet make high priority demands on our attention and our resources. We must also realize that space expenditures must take their proper place within a rigorous system of national priorities."

While the recommendation to build a space station and a space shuttle was accepted, NASA’s share of the federal budget was dramatically trimmed from a peak of 4 percent to roughly 1 percent. Eventually, Nixon also delayed the construction of the space station in favor of a much more modest Skylab experiment, which was launched in 1974. Three planned moon landings were also canceled. NASA began to pursue the space shuttle project.

The space program under Nixon became more modest. He also worked to shift the emphasis from competition with the Soviet Union to cooperation. In May 1972 Nixon visited Moscow, becoming the first President to do so and only the second President to visit the Soviet Union. On May 24, Nixon and Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin signed an agreement to cooperate in space exploration. This agreement led to the 1975 linking of an Apollo spacecraft with a Soyuz command module.

Historians will continue to write about Nixon’s foreign policies, his relationships with China and the Soviet Union, and his decisions regarding the Vietnam War. And the Watergate affair will continue to be told and retold as additional documents and tapes are released.

But what will have the most impact on Americans in the decades to come may grow out of the domestic programs, proposals, and policies from the Nixon years. Environmental laws and regulations affect us everywhere. Work safety laws reach us in the workplace. Affirmative action initiatives of various sorts inject more diversity into every aspect of our democracy.

Many of Richard Nixon’s domestic policies are considered anathema to some Republicans today, especially those that impose regulations on businesses. But they reflected his view as a mainstream Republican of the time, who believed that there was a role for the federal government in the lives of its citizens and in the nation’s economy.

In a 1965 speech, Nixon placed himself on the political ideological scale: “If being a liberal means federalizing everything, then I’m no liberal. If being a conservative means turning back the clock, denying problems that exist, then I’m no conservative.”

Note on Sources

The records and holdings of the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum in Yorba Linda, California, provide a wealth of information on the domestic policies of the Nixon White House.

For this article, Leonard Garment’s files on the Philadelphia Plan and other issues related to discrimination in the workplace were used to add further insight on how the White House viewed the politics of its labor policies. Segments of the President’s public speeches were taken from the Public Papers of the Presidents: Richard Nixon. The memoirs of Richard Nixon, RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990), were also used to highlight the President’s own thoughts on his approach to civil rights issues and how his former football coach may have influenced his Native American policies. The Haldeman Diaries: Inside the Nixon White House (New York: Berkley Books, 1994) also gave another level of insider information about the Nixon White House. In the section on Title IX , the National Center for Education Statistics was used to show the numerical breakdown of national college enrollment based on gender.

This article also used the following secondary sources: James C. Cobb, The South and America Since World War II (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011); W. David Compton, Where No Man Has Gone Before: A History of Apollo Lunar Exploration Missions (NASA Special Publication-4214 in the NASA History Series, 1989); T. A. Heppenheimer, The Space Shuttle Decision (NASA Special Publication-4221 in the NASA History Series, 1998); Dean J. Kotlowski, “Civil Rights Policy,” A Companion to Richard M. Nixon, ed. Mel Small (West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011); Kotlowski’s Nixon’s Civil Rights: Politics, Principle, and Policy (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001); John M. Lodgson’s “Ten Presidents and NASA,” www.nasa.gov/50th/50th_ magazine/10presidents.html https://web.archive.org/web/20230419024501/www.nasa.gov/50th/50th_magazine/10presidents.html; and Walter McDougall, The Heavens and the Earth: A Political History of the Space Age (Basic Books: New York, 1985).