A Heart of Purple

The Story of America’s Oldest Military Decoration and Some of Its Recipients

Winter 2012, Vol. 44, No. 4

By Fred L. Borch

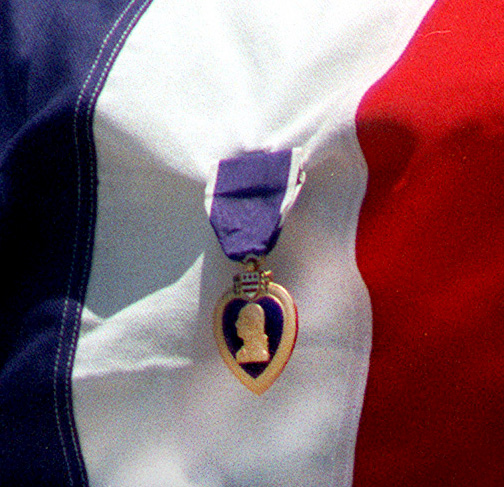

The distinctive color and unusual shape of the Purple Heart may be the reason Americans seem to recognize it more than any other military decoration—even the prestigious Medal of Honor.

Many Americans also know that the Purple Heart is given to those who are wounded or killed while fighting in the nation’s wars. What most Americans do not realize, however, is that the Purple Heart is a unique military award

It is the oldest U.S. military decoration; Gen. George Washington awarded the first purple-colored heart-shaped badges to soldiers who fought in the Continental Army during the American Revolution.

Finally, the Purple Heart is the only decoration awarded without regard to any person’s favor or approval. Any soldier, sailor, airman, marine, or Coast Guardsman who sheds blood in defense of the nation automatically receives the Purple Heart. The history of this unique decoration—and some of its recipients—is worth telling, and is only possible because of documents and photographs preserved in the National Archives and Records Administration.

On August 7, 1782, General Washington made this announcement in his Orders of the Day:

"The General ever desirous to cherish a virtuous ambition in his soldiers, as well as to foster and encourage every species of Military Merit, directs that whenever any singularly meritorious action is performed, the author of it shall be permitted to wear . . . over his left breast, the figure of a heart in purple cloth. . . . Not only instances of unusual gallantry but also of extraordinary fidelity and essential service . . . shall be awarded."

Historians can verify only three awards of the original purple, heart-shaped Badge of Military Merit, although they suspect there were more.

Sgt. Daniel Bissell received his purple heart for spying on British troops quartered in New York City and then returning to American lines with invaluable intelligence. Sgt. William Brown received the decoration for gallantry while assaulting British redcoats at Yorktown in October 1781. Finally, Sgt. Elijah Churchill was awarded his Badge of Military Merit for heroism on two daring raids conducted by Continental soldiers against British fortifications on Long Island.

In the years following the Revolution, Washington’s Badge of Military Merit fell into disuse and was forgotten for almost 150 years.

Revival of the Purple Heart a Century and a Half Later

When Gen. John J. Pershing and the American Expeditionary Force arrived in Europe in 1917, the only existing American decoration was the Medal of Honor. Pershing and his fellow commanders—and American soldiers—soon became acutely aware that the British and French armies had a variety of military decorations and medals that could be used to reward valor or service.

By the end of World War I, the Army and Navy had some additional medals as, in 1918, Congress passed legislation creating the Army’s Distinguished Service Cross, the Navy Cross, and Distinguished Service Medals for both services.

But these new medals, while giving much deserved recognition to many soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines, required such a high degree of combat heroism or meritorious service that some civilian and military leaders in Washington believed that another decoration was required—one that could be used to reward individuals of more junior rank for their valuable wartime services.

In the 1920s, the War Department studied the issue, and a few officers with knowledge of Washington’s old Badge of Military Merit suggested that it be resurrected, renamed the “Order of Military Merit,” and awarded to any soldier for exceptionally meritorious service or for a heroic act not performed in actual conflict. Ultimately, however, no action was taken on this proposal to revive the Badge of Military Merit.

With the appointment of Gen. Douglas MacArthur as Army Chief of Staff in 1930, however, there was interest in the suggestion for a new medal.

A few months after MacArthur pinned four stars on his shoulders and began serving as Army Chief of Staff, he wrote to Charles Moore, the chairman of the Commission of Fine Arts, and informed Moore that the Army planned to “revive” Washington’s old award on the bicentennial of his birth.

As a result, on February 22, 1932, the War Department announced in General Orders No. 3 that “the Purple Heart, established by General George Washington in 1782,” would be “awarded to persons who, while serving in the Army of the United States, perform any singularly meritorious act of extraordinary fidelity or essential service.

Then, in a parenthetical in this announcement, the Army published the following sentence: “A wound, which necessitates treatment by a medical officer, and which is received in action with an enemy of the United States, or as a result of an act of such enemy, may . . . be construed as resulting from a singularly meritorious act of essential service.”

This meant that the Purple Heart was an award for high-level service. But it also meant that an individual serving “in the Army” who was wounded in action could also be awarded the Purple Heart. Not all wounds, however, qualified for the new decoration. Rather, the wound had to be serious enough that it “necessitated” medical treatment.

From 1932 until the outbreak of World War II, the Army awarded some 78,000 Purple Hearts to living veterans and active-duty soldiers who had either been wounded in action or had received General Pershing’s certificate for meritorious service during World War I. The latter was a printed certificate signed by Pershing that read “for exceptionally meritorious and conspicuous services.”

While the vast majority of Purple Hearts were issued to men who had fought in France from 1917 to 1918, a small number of soldiers who had been wounded in earlier conflicts, including the Civil War, Indian Wars, and Spanish-American War, applied for and received the Purple Heart.

A final point about these pre–World War II Purple Hearts is worth mentioning: there were no posthumous awards. As MacArthur explained in 1938, the Purple Heart—like Washington’s Badge of Military Merit—was “not intended . . . to commemorate the dead, but to animate and inspire the living.” Consequently, said MacArthur, the Purple Heart could not be awarded posthumously. “To make it a symbol of death, with its corollary depressive influences,” insisted MacArthur, “would be to defeat the primary purpose of its being” (emphasis added).

Changes to the Purple Heart During World War II, Vietnam

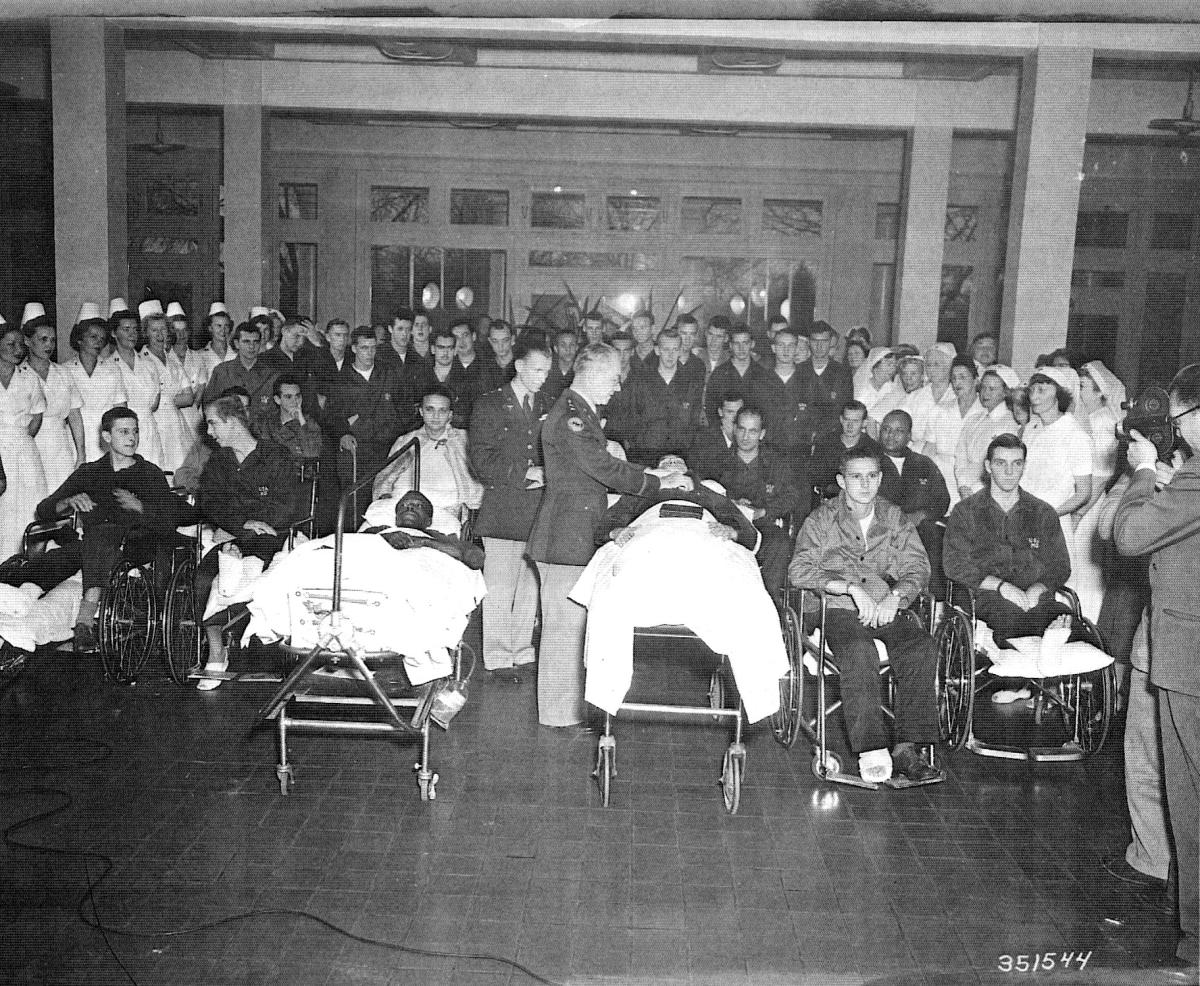

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, and the deaths of thousand of soldiers in Hawaii and the Philippines, the War Department abandoned MacArthur’s “no posthumous award” policy. On April 28, 1942, the Army announced that the Purple Heart now would be awarded to “members of the military service who are killed . . . or who died as a result of a wound received in action . . . on or after December 7, 1941.” But note that this change in policy only applied to those killed after the Japanese attack on Hawaii; posthumous awards of the Purple Heart for pre–World War II conflicts still were not permitted.

Five months later, the Army made another major change in the award criteria for the Purple Heart: it restricted the award of the Purple Heart to combat wounds only. While MacArthur’s intent in reviving the Purple Heart in 1932 was that the new decoration would be for “any singularly meritorious act of extraordinary fidelity or essential service” (with combat wounds being a subset of such fidelity or service), the creation of the Legion of Merit in 1942 as a new junior decoration for achievement or service meant that the Army did not need two medals to reward the same thing.

The result was that the War Department announced that, as of September 5, 1942, the Purple Heart was now exclusively an award for those wounded or killed in action. About 270 Purple Hearts for achievement or service—and not for wounds—were awarded before this change in policy, which makes them exceedingly rare.

A final change in the evolution of the Purple Heart was President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s decision to give the Navy Department the authority to award the decoration. This occurred on December 3, 1942—almost a year after the attack that had propelled the United States into World War II. That day, Roosevelt signed an executive order giving the Secretary of the Navy the authority to award the Purple Heart to any sailor, marine, or Coast Guardsman wounded in action against an enemy of the United States or killed in any action after December 7, 1941.

As strange as it may seem, until this time the Purple Heart was an Army-only award, and the Navy had no authority to award it. Even so, sailors and marines did sometimes receive the decoration; if they were “serving with” the Army, they were eligible. Consequently, a handful of marines serving in the AEF in World War I received the Purple Heart on the basis of wounds received while fighting alongside soldiers in France in 1917 and 1918.

The next major change to the award criteria for the Purple Heart occurred during the presidency of John F. Kennedy. When American soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines serving in South Vietnam began being killed and wounded, they were not eligible for the Purple Heart because they were serving in an advisory capacity rather than as combatants. Additionally, because the United States was not formally a participant (as a matter of law) in the ongoing war between the South Vietnamese and the Viet Cong and their North Vietnamese al-lies, there was no “enemy” to satisfy the requirement of a wound or death received “in action against an enemy.”

Since Kennedy recognized that the Purple Heart should be awarded to these uniformed personnel who were shedding blood in South Vietnam, he signed an executive order on April 25, 1962. That order permitted the Purple Heart to be awarded to any per-son wounded or killed “while serving with friendly foreign forces” or “as a result of action by a hostile foreign force.”

By 1973, when the last U.S. combat forces withdrew from Vietnam, thousands and thousands of Americans wounded or killed by the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese had been awarded the Purple Heart.

Kennedy’s decision to expand the award criteria for the Purple Heart also meant that servicemen killed or wounded in lesser- known actions, such as the Israeli attack on the USS Liberty in 1967 and the North Korean seizure of the USS Pueblo in 1968, also could receive the Purple Heart.

Changes to the Purple Heart From Vietnam to the Present

The next major changes to the Purple Heart occurred in February 1984, when President Ronald Reagan recognized the changing nature of war and signed Executive Order 12464. This order announced that the Purple Heart could now be awarded to those killed or wounded as a result of an “international terrorist attack against the United States.

Reagan also decided that the Purple Heart should be awarded to individuals killed or wounded “outside the territory of the United States” while serving “as part of a peacekeeping mission.”

As a result of Reagan’s decision, a small number of Americans in uniform received the Purple Heart who otherwise would have been denied the medal. For example, a sailor who had been assassinated by Turkish leftists in Istanbul was posthumously awarded the decoration, and a naval officer wounded while serving in Lebanon as a UN military observer also received the Purple Heart

Finally, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have caused the most recent changes to the Purple Heart’s award criteria.

On April 25, 2011, the Defense Department announced that the decoration now could be awarded to any soldier, sailor, airman, or marine who sustained “mild traumatic brain injuries and concussive injuries” in combat. This decision was based on the recognition that brain injuries caused by improvised explosive devices qualify as wounds, even though such brain injuries may be invisible.

Awards for these head injuries are retroactive to September 11, 2001, the day of al Qaeda’s attack on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. On the issue of severity of a brain injury, a soldier or airman need not lose consciousness in order to qualify for the Purple Heart. On the contrary, if a “medical officer” or “medical professional” makes a “diagnosis” that an individual suffered a “concussive injury” and the “extent of the wound was such that it required treatment by a medical officer,” this is sufficient for the award of the Purple Heart. It is too early to know the extent to which Purple Hearts will be awarded to soldiers for these concussion injuries, but the number of awards could be sizable given the wounds inflicted by improvised explosive devices.

The Purple Hearts for traumatic brain injury are very different from the ongoing issue of whether the Purple Heart should be awarded for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). In 2008, after increasing numbers of men and women returning from service in Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom were diagnosed as suffering from PTSD, some commentators proposed awarding the Purple Heart for these psychological wounds.

After carefully studying the issue, however, the Defense Department concluded that having PTSD did not qualify a person for the Purple Heart because the disorder was not a “wound intentionally caused by the enemy . . . but a secondary effect caused by witnessing or experiencing a traumatic event.” This is not to say that PTSD is not a serious mental disorder—but those who suffer from it may not receive the Purple Heart.

As war evolves and changes, the Purple Heart will evolve as well. But, while today’s Purple Heart medal looks exactly the same as it did in 1932, General MacArthur would certainly be surprised to see how much the criteria for awarding it has changed. Today, the Purple Heart may be awarded to any member of the Armed Forces of the United States who, while serving under competent authority in any capacity with one of the Armed Forces after April 5, 1917, is killed or wounded in any of the following circumstances:

- in action against an enemy of the United States,

- in action with an opposing armed force of a foreign country in which the Armed Forces of the United States are or have been engaged,

- while serving with friendly foreign forces engaged in an armed conflict against an opposing armed force in which the United States is not a belligerent party,

- as the result of an act of any such enemy or opposing armed force,

- as the result of an act of any hostile foreign force,

- as the result of friendly weapon fire while actively engaging the enemy, or

- as the indirect result of enemy action (for example, injuries resulting from parachuting from a plane brought down by enemy or hostile fire).

Recipients of the Purple Heart Include the Famous and Non-Famous

More than a million American men and women have received the Purple Heart since 1932, including more than 25,000 during the ongoing wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. While one might expect that only those wounded after 1932 would have received the Purple Heart, most early recipients were World War I soldiers (and marines serving with the Army in France) who had been wounded in action.

But veterans of the Civil War and Indian Wars, as well as the Spanish-American War, China-Boxer Rebellion, and Philippine Insurrection, also received the Purple Heart. They were eligible because the 1932 Army regulations governing the medal’s award allowed any soldier who had been wounded in any conflict involving U.S. Army personnel to apply for the new medal.

The Adjutant General’s Office (AGO) recorded pre-1940 applications on 3- by 5-inch index cards, listing the name, rank, unit, date of wounding, and date of issuance of the medal. These “AGO award cards,” now housed at the National Archives at St. Louis, Missouri, are priceless archival evidence that an individual was awarded a Purple Heart for wounds received in a pre-1940 conflict—and almost always are the only official proof of entitlement to a Purple Heart.

A Medal of Honor First, a Purple Heart 55 Years Later

There is at least one exception to the rule that an AGO award card is the only proof of a Purple Heart.

Witness the unusual case of Calvin Pearl Titus, who, awarded the Medal of Honor for heroism in China during the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, received his Purple Heart from the Army more than half a century later.

Born in Iowa in 1879, Titus enlisted in the Iowa National Guard in 1898 and, two years later, was in China as a corporal and bugler in the Regular Army’s 14th Infantry Regiment. On August 14, 1900, during the heavy fighting in Peking, Titus overheard his commander wondering if the 30-foot-high Tartar Wall could be scaled. He answered with the now-famous reply, “I’ll try, sir.”

The Americans had no ropes or ladders, but Titus, by holding onto exposed bricks and crevices in the ancient wall, managed to climb to the top. Other soldiers then followed his courageous example, and soon two companies of soldiers were in control of the wall. Their covering fire subsequently allowed British troops to breach the Boxers’ stronghold.

Titus was recommended for the Medal of Honor for his extraordinary heroism at Peking, and he also received an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy. Titus was at West Point as a cadet when President Theodore Roosevelt presented him with the Medal of Honor—and he remains the only West Point cadet in history to be awarded America’s highest award for combat valor while attending classes there.

Although Titus was not wounded while climbing the Tartar Wall, a letter in his official military file records that he was wounded the next day. As a result of this injury acquired “in line of duty,” the Army awarded Titus the Purple Heart on February 17, 1955. The only existing proof of his award is this letter

For Lieutenant Murphy, a Purple Heart and a Career in the Movies

Another famous soldier recipient of the Purple Heart was Audie L. Murphy, who was awarded three Purple Hearts. His first award was for injuries received when then-Sergeant Murphy was caught in a mortar barrage while fighting near Vy-les-Lure, France, in September 1944. While Murphy waited for the enemy fire to stop, a shell exploded at his feet and knocked him unconscious. A fragment of metal from that shell also pierced his foot.

The following month, now-Lieutenant Murphy (he had received a battlefield commission) was wounded when a bullet fired by a German sniper struck his right hip. Murphy spent three months in the hospital recovering from this serious injury. After rejoining his unit in January 1945, Murphy was wounded a third time when he was hit by fragments from a German mortar round that killed two others nearby.

When World War II ended, Audie Murphy was still a month shy of his 21st birthday. But he was the most highly decorated soldier in the 8-million-strong Army, with a Medal of Honor, a Distinguished Service Cross (the second highest decoration that may be awarded to an American soldier), two Silver Stars, and two Bronze Stars in addition to his three Purple Hearts.

Murphy returned to the United States as a hero. His face graced the cover of Life magazine, and after visiting Hollywood at the invitation of actor James Cagney, Murphy began appearing in movies. Over the next 20 years, he had roles in more than 40 movies. Many critics consider his best performance to have been in Red Badge of Courage in 1951, but his portrayal of himself in To Hell and Back in 1955 also received high marks.

Purple Hearts to Maverick—and Marshal Matt Dillon

Two other celebrity recipients of the Purple Heart—known to virtually every American born in the 20th century—are James K. Arness and James Garner.

Arness, beloved to countless fans as U.S. Marshal Matt Dillon in the long-running television series Gunsmoke, received his Purple Heart after being badly wounded in his right leg by enemy machine-gun fire in France on February 1, 1944. Arness spent more than a year in the hospital recovering from this injury.

Garner, who starred as professional gambler Bret Maverick in the television series Maverick and as private detective Jim Rockford in The Rockford Files, was awarded two Purple Hearts for wounds received during the Korean War. Garner had been in Korea just two days when he was hit in the hand and face by enemy shrapnel. Some months later, in April 1951, Garner was injured a second time when U.S. Navy F9F Panther jets firing 20mm rockets mistakenly attacked Garner and his fellow soldiers. Garner was hit in the buttocks, he had phosphorous burns on his neck, and his rifle was shattered.

The only U.S. President to be awarded the Purple Heart is John F. Kennedy. He received the Purple Heart after being seriously injured when the patrol torpedo boat (PT-109) he was commanding was sliced in half and sunk by a Japanese warship near in the Solomon Islands in August 1944. Kennedy was badly hurt in the collision, as were two other sailors; two more were lost. Despite his injuries, then Lieutenant (junior grade) Kennedy “unhesitatingly braved the difficulties and hazards of darkness to direct rescue operations, swimming many hours to secure aid and food after he had succeeded in get-ting his crew to shore” on a nearby island. Kennedy’s brush with death was popularized in newspapers and magazines, and his status as a war hero helped smooth his entry into Massachusetts politics.

Journalist Ernie Pyle Reported the GIs’ Stories

Another celebrity who received a Purple Heart was the famous war correspondent Ernest “Ernie” Pyle. He was killed in April 1945 by Japanese machine-gun fire while accompanying elements of the Army’s 77th Infantry “Statute of Liberty” Division. Pyle is arguably the most famous civilian recipient of the Purple Heart. Known to family and admirers as “Ernie,” he smoked Bull Durham tobacco and rolled his cigarettes with one hand.

There was nothing pretentious about Ernie Pyle. He was a career newspaperman when he was sent to England in 1940 to report on the bombing of London, and he subsequently covered the invasions of North Africa, Sicily, and Italy in 1943 and of Normandy in 1944. His winning personality and frontline reporting made him popular with both combat troops and Americans back home.

Pyle won a Pulitzer Prize for journalism in 1943. In a column written from Italy in 1944, Pyle proposed that combat soldiers be given “fight pay” similar to an airman’s flight pay. In May of that year, Congress acted on Pyle’s suggestion, giving soldiers 50-percent extra pay for combat service, legislation nicknamed “the Ernie Pyle bill.” Today’s hazardous duty pay and other benefits given by Congress to today’s combat troops trace their roots to Pyle’s idea.

Pyle was reporting on the island of Ie Shima, near Okinawa, on April 18, 1945, when his luck ran out, and he was killed. Secretary of the Army John O. Marsh posthumously awarded the Purple Heart to Pyle on April 28, 1983, 38 years after Pyle lost his life. While awards of the Purple Heart to civilians are prohibited today, there is no doubt that Ernie Pyle deserved his decoration.

A General and a Colonel Each Have Record Eight Purple Hearts

Who has the record for the most Purple Hearts? Military records in the National Archives in St. Louis identify a number of possibilities, with the two strongest contenders being Maj. Gen. Robert T. Frederick and Col. David H. Hackworth.

Both soldiers received a remarkable eight awards of the decoration.

All eight of Frederick’s Purple Hearts were awarded during World War II, with an unprecedented three Purple Hearts being awarded on the single day of June 4, 1944. On that day, he was wounded on three separate occasions by bullets that struck his thighs and right arm. Frederick received his eighth Purple Heart—just six days after he had pinned on his second star—when he was wounded while leading a parachute assault near Saint-Tropez, France.

Hackworth received four Purple Hearts for combat wounds received in the Korean War and another four for wounds received while fighting in Vietnam. In addition to these eight Purple Hearts, Hackworth received an unprecedented 10 Silver Stars for gallantry in action.

After retiring from the Army, Hackworth had a successful career as a controversial magazine columnist for Newsweek magazine and wrote a number of best-selling books on military topics, including About Face: The Odyssey of an American Warrior, which was published in 1989.

A Final Note

The Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard do not maintain a centralized database of military awards. Consequently, there is no readily available list of Purple Heart recipients, much less a list of multiple awards. There may be a soldier, sailor, airman or marine who “beats” the Frederick-Hackworth Purple Heart total, but this would require official confirmation in official personnel files maintained by the National Archives in St. Louis.

More than a million Purple Hearts have been awarded since General Washington’s Badge of Military Merit was revived in 1932. The unique heart-shaped decoration continues to be widely recognized by Americans. It also continues to be prized by all who receive it, probably because the award of a Purple Heart does not depend on any superior’s favor or approval.

The Purple Heart is unique as an egalitarian award in a nondemocratic, hierarchical organization, since every man or woman in uniform who sheds blood or receives a qualifying injury while defending the nation receives the Purple Heart regardless of position, rank, status, or popularity.

Fred L. Borch is the regimental historian and archivist for the Army’s Judge Advocate General’s Corps. A lawyer and historian, he served 25 years active duty as an Army judge advocate before retiring in 2005. Awarded a Fulbright for the Netherlands for 2012–2013, he is currently a visiting professor at the University of Leiden. This is his fifth article for Prologue.

Note on Sources

Official records relating to the revival of the Purple Heart in 1932 are located in Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1917–. Decimal files 200.6 contain information on the Purple Heart and other decorations and medals. Official records pertaining to the design of the Purple Heart are in Record Group 66, Commission of Fine Arts, Entry 4.

The National Personnel Records Center, in St. Louis, Missouri, holds the Adjutant General’s Office 201 award cards. These 3- by 5-inch index cards list, by surname, all pre-1940 recipients of the Medal of Honor, Distinguished Service Cross, Distinguished Service Medal, Silver Star, and Purple Heart. Since about 80 percent of the official records for Army personnel discharged between 1912 and 1960 were destroyed in a 1973 fire at the records depository in St. Louis, these AGO award cards are the only archival proof of award eligibility for many World War I recipients.

Verification of the Purple Hearts awarded to Calvin Titus, Audie Murphy, James Arness, James Garner, Ernest Pyle, John F. Kennedy, Robert Frederick, and David Hackworth is contained in their official military personnel records at National Archives at St. Louis.

War Department Circular No. 6, dated February 22, 1932, announced the revival of the Purple Heart as an Army decoration and the criteria for the new award. All subsequent changes in criteria were published in Army Regulations 600-45, 672-5-1, and 600-8-22. Information on the Roosevelt, Kennedy, and Reagan executive orders expanding award criteria for the Purple Heart are located on the National Archives website at www.archives.gov/federal-register/executive-orders/; the text of the orders may be found at www.presidency.ucsb.edu/index.php.

An excellent printed official source on post-Vietnam Purple Heart awards is Madeline Sapienza, Peacetime Awards of the Purple Heart in the Post-Vietnam Period (Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, 1987). For a secondary source, see Fred L. Borch, For Military Merit: Recipients of the Purple Heart (Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 2010).