Dangers in the Civilian Conservation Corps

Accident Reports, 1933–1942

Winter 2011, Vol. 43, No. 4 | Genealogy Notes

By Kenneth Heger

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was one of the New Deal's first programs and arguably one of its most popular.

In existence between 1933 and 1942, the CCC employed millions of unmarried men between the ages of 17 and 25 on projects in rural areas owned primarily by federal, state, and local governments. Enrollees usually served a term of six months, but they could serve up to four terms. They earned $30 a month, $25 of which was sent home to their families.

The CCC performed more than 150 different kinds of work, most of which consisted of manual labor, and operated in every state and territory. The men built hiking trails, roads, park and forest buildings; constructed bridges; planted trees; and put out forest fires. Camps also offered vocational training and basic education in academic subjects, such as arithmetic and grammar.

Given the nature of the work and the inexperience of most enrollees, accidents were inevitable, so the CCC established the Division of Safety. The division directed safety, health, sanitation, fire prevention, and compensation throughout the CCC's camps. To improve safety measures and to provide as much information about an incident to family members in the case of serious injury or death, the division investigated accidents to determine their cause.

The case studies that follow illustrate how rich the accident reports can be for family historians.

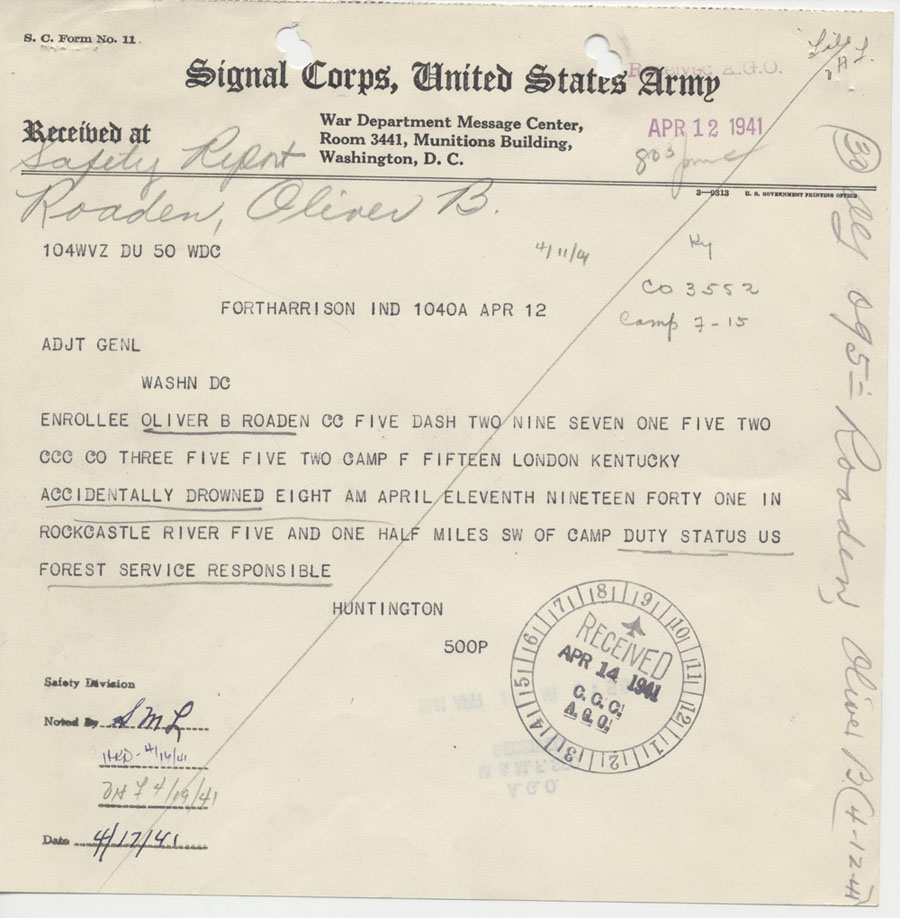

Oliver B. Roaden

April 11, 1941, started like any other day at CCC Camp F-15 in London, Kentucky. The enrollees got up, did their calisthenics, ate breakfast, and prepared to go to work.

Located in the Daniel Boone National Forest, Camp F-15 was engaged in numerous activities to safeguard and improve the forest. The enrollees built roads and hiking trails. They erected bridges across streams and creeks. They put up telephone lines. They built fire towers and put out forest fires.

On this day, their task was to continue work on the bridge spanning the Rockcastle River. The structure, a 120-foot steel truss bridge, required teams of men working on both sides of the river to complete it on time. Early in the day, Robert M. Williams, junior foreman and leader of the work crew, assembled his men and headed out on the four-and-a-half mile trip to the construction site.

Oliver B. Roaden was part of Williams's work crew. Roaden, an assistant leader in the technical service, served as a camp blacksmith. Roaden had worked on the Rockcastle River Bridge for several days at the end of March before returning to camp to concentrate on his blacksmithing duties.

At the work site, the crew divided up to tackle different parts of the work. Williams assigned Roaden and two of his colleagues, Earnest Brock and Edgar B. Bowling, the task of crossing the river to carry supplies for Camp F-15's satellite camp and to work on the concrete forms for the bridge's pier caps. The three enrollees began loading their flat-bottom boat with tools as well as 20½ pints of milk and 10 pounds of meat for the satellite camp.

Prior to shoving off, Williams asked Roaden if he would be able to row the boat across the river. Earlier in the week the area had heavy rainfall, and the Rockcastle was still running about two feet higher than normal. Because the bridge site was only about 135 feet above a series of rapids, Williams wanted to make sure Roaden felt comfortable with his task. Roaden replied that he could make the trip. Since Roaden had a reputation for being a strong swimmer and had rowed the boat across the river before without incident, Williams agreed and returned to work.

Shortly before 8 a.m., the crossing started as planned. Once Roaden started out, the strong current grabbed the boat and pushed it down the river about five feet away from the route leading to the landing. All three passengers became excited, fearing the rapids downriver. Roaden told Brock and Bowling to jump out of the boat and swim to the shore. Because the landing spot was in a sheltered cove among some large rocks, it would be easy for the two men to get ashore. Roaden calculated that without the additional weight of his two passengers, he could regain control of the boat and guide it back to the landing.

Brock and Bowling jumped and swam safely to shore. The force of the two men jumping out of the boat resulted in a wave large enough to push the vessel further into the river's main channel. The boat's pace toward the rapids accelerated. Roaden paddled furiously to regain control but without success.

Quickly approaching the rapids, Roaden decided to jump and rely on his swimming skills to reach the shore. He was 25 feet from the rapids.At this point Williams saw Roaden swimming gallantly against the current. Despite being a good swimmer, Roaden was hampered by bulky and heavy clothing, and he began to panic.

Williams hurried to assist Roaden. He waded into the river to try to grab Roaden's outstretched arms but was unsuccessful. He returned to shore, almost being swept away by the current himself, and yelled to the assembling work crew to bring him something to reach Roaden. Williams rushed to the bridge piers and climbed out on them, extending tree limbs and brush in a vain attempt to reach Roaden.

The current carried Roaden over the rapids. He had almost righted himself when he got caught in an eddy that turned him around, further disorienting him. By that time, Roaden was exhausted. He went under once but resurfaced. The second time he went under, he disappeared.

While trying to reach Roaden, Williams had sent several workers down the road to get help from a local farmer. By the time the farmer brought his boat, additional help had arrived from the camp. The men used iron from the construction site to fashion hooks to try to retrieve Roaden from the river.

Alzono Mills (the camp's assistant section mechanic) took the lead, but even this process proved difficult. In his first foray into the river, Mills got tangled in the rope and almost drowned. A second attempt got the body to shore. It was 8:50 a.m.; the ordeal had lasted almost an hour.

When they recovered the body, it was cold and pulseless. Robert May, the camp's first aid instructor, tried to revive Roaden, performing artificial resuscitation on him for about 30 minutes. The county fire department arrived about 9:15 a.m. and also performed artificial resuscitation. Nothing worked.

The workers brought Roaden's body back to the camp. At 10:45 a.m., William McHague, the county coroner and contract undertaker for the camp, removed the body and took it to the funeral home in London. Two days later, Roaden's family retrieved his body for burial in his home town of Corbin, Kentucky. Roaden was only 20 years, 8 months, and 1 day old when he died.

Herbert Knodel

Herbert Knodel of Isabel, South Dakota, served several tours of duty in the CCC. He served two consecutive six-month terms between April 1939 and March 1940, when he worked in the camp in Roubaix, South Dakota. He performed his duties well and received an honorable discharge.

In October 1940, Knodel began what was to be his third six-month stint. His entrance physical was routine. The five-foot-eight-inch Knodel weighed in at 145 pounds. The doctor reported the enrollee had black hair, and a ruddy completion. His eyes were gray, and his vision was 20/20 in both eyes. His cardiovascular system, muscular structure, lungs, and mental condition all checked out as normal. He began his assignment at Camp NP-2 in Wall, South Dakota that month.

By the end of the year, Knodel's health had taken a turn for the worse. Around Christmas, he became ill. The camp physician made a diagnosis of influenza and sent him to the camp's infirmary. Knodel seemed to be well enough to travel, and the camp commander allowed him to go home for New Year's.

Upon returning to the camp, Knodel complained of pain and stiffness in several joints. The camp physician confined him to the infirmary again. His condition worsened, and on February 10, 1941, the physician transferred Knodel to the military hospital in Fort Meade, South Dakota.

Knodel's condition waxed and waned. On February 16, the hospital reported Knodel's joints were still swollen, and he had no appetite. The reports for the first 10 days of March indicated that Knodel felt somewhat better, and his joints did not ache.

In May, Knodel began to complain about chest pains and difficulty breathing. X-rays showed his heart was enlarged, and there were problems with his liver. Despite the occasional relief from pain, Knodel's condition worsened. In August, the hospital began to administer glucose. He lost 25 pounds. His liver began to shrink. His feet swelled. On September 4, 1941, at 5:15 p.m., Knodel finally succumbed to his ailments and died. He was 19 years, 6 months, and 26 days old. The hospital returned Knodel's body to his parents for burial in Isabel.

The investigating board's report was short. The single-page document recorded that Knodel had died of rheumatic fever. It determined that his death was not due to traumatic injury and that Knodel was not under the influence of alcohol. It also indicated that Knodel's death did not occur in the performance of duty and was not due to his own misconduct.

Learn more about:

- The first year of the CCC.

- CCC enrollee records.

- CCC records described in the National Archives Catalog.

Butler J. Killingsworth

In 1940 Butler J. Killingsworth was a 17-year-old enrollee at Camp BS-2 in Absecon, New Jersey. On June 6, he and fellow enrollee William L. Harris had the task of installing screen windows in the camps buildings to prepare them for summer weather. About 11 a.m., Camp Commander Leonard H. Smith, Jr., and his subordinate officer Martin N. Block arrived at the camp's workshop for inspection. Smith and Block noted that the circular saw was not properly installed. There was no plug on the power cord, and in place of a plug, someone had simply stuck two bare wires in the nearest electrical socket. Smith ordered the workshop employees to take the saw out of commission until they could repair it. Killingsworth and Harris were in the room at the time, standing about 10 feet from Smith when he made the announcement.

Despite the commander's instructions, Killingsworth operated the saw. Around 2 p.m., he had an accident. While using the saw to cut a block of wood for the window frames, a piece of the wood got stuck in the saw guard. When attempting to remove the blockage, the saw slipped and cut Killingsworth's left hand, severely injuring three fingers.

Camp doctors treated Killingworth for several days. On the June 10, realizing the young man needed surgery, Smith contacted Killingsworth's parents to get their permission to admit him to the hospital. The official diagnosis was a severe laceration to the middle finger of his left hand. The ring finger suffered a mildly severe abrasion. The saw did the most damage to the index finger. The damage was so great that the doctors amputated the finger above the first interphalangeal joint. The hospital released him on July 1.

Killingsworth suffered a 5-percent permanent disability as a result of the accident. Perhaps the only good news was the outcome of the official investigation into the matter. The investigating panel found that Killingsworth was not to blame for the accident. Since the reported problem with the saw—the bare wires in the outlet—was not the cause of the accident, Killingsworth was not reprimanded. Indeed, the panel characterized the accident as having occurred during the normal course of his duties.

Charles E. Wigand and Ralph D. Wigger

Not every accident at a CCC camp resulted in death or serious injury. Reports documented non–life-threatening injuries as well. Take the cases of Charles E. Wigand and Ralph D. Wigger.

In fall 1938, 18-year-old Charles E. Wigand of McKeesport, Pennsylvania, served in several camps in the Prescott, Arizona, area and suffered a series of minor accidents. On October 12 he was tightening a nut on a truck when the wrench slipped and cut the middle finger of his right hand. Six days later he was working on the same truck and reinjured his right hand. On November 1, Wigand slashed a finger on his right hand on an exposed nail on the door of his barracks.

Wigand did not report an of these injuries or go to the infirmary. He finally received medical treatment in early December, when his foreman, Jes R. Smith, noticed he was favoring the hand. Smith reminded Wigand that enrollees were to report injuries promptly so they could receive proper treatment. Wigand was lucky. When he finally went to the infirmary on December 19, medical treatment indicated that he would suffer no permanent damage and could return to work full time on December 30.

Ralph D. Wigger suffered a similar accident at Camp F-24 in Cody, Wyoming. On February 7, 1939, the 18-year-old was peeling potatoes when his knife slipped. He cut the index finger on his right hand and grazed the palm of his left hand. The injury was minor; he only missed a week's worth of work.

Types of Documents in the Accident Reports

The preceding narratives illustrate how valuable Civilian Conservation Corps accident reports can be to your research. The reports are part of Record Group 35, Records of the Civilian Conservation Corps, in the National Archives. They form two series of records:

Official Reports of Injury, 1937–1940 (Preliminary Inventory 11, Records of the Civilian Conservation Corps, Entry 118), National Archives Identifier 1040709; and Reports of Accidents and Injuries, 1933–1942 (Preliminary Inventory 11, Records of the Civilian Conservation Corps, Entry 119), National Archives Identifier 1040622.

Both series are arranged alphabetically by the surname of the person who had the accident. In addition to documenting accidents that resulted in death and personal injury, reports detail damage to government and private property and give accounts of serious illnesses of enrollees. Each indexed file has a unique ARC identifier.

Files vary in size. Some are fairly thin; others can be voluminous. The reports of Boards of Inquiry provide the bulk of the documentation. The reports usually contain an overview of the facts of the event and the board's conclusion on whether the accident was in the line of duty, the result of misconduct, or unrelated to CCC business. The files can also include witness statements, affidavits, death certificates, copies of service records, and other documents containing information on the enrollee. The files on the case studies above illustrate the differences among files.

Roaden's file is large. It contains correspondence with CCC officials concerning the accident investigation, a 14-page accident report that includes the facts of the incident as well as testimony from the people at the scene, a copy of Roaden's death certificate listing his parents' names, and several photographs. While reports of deaths usually include a copy of the death certificate, photographs are a rare treasure. Roaden's file is part of Official Reports of Injury, 1937–1940, and its unique ARC identifier is 1098000.

Knodel's file is fairly slim but contains documents of great value. In addition to the investigation report, the file includes a copy of Knodel's death certificate. The two-page clinical report compiled by the staff at Fort Meade's hospital provides an overview of Knodel's health prior to admission, a snapshot of his family (he had 11 brothers and a sister), and a very detailed report of the progress of his illness. In addition, the file includes Knodel's 1940 Individual Record form compiled at the time of his reenrollment in October 1940. Knodel's file is part of Official Reports of Injury, 1937–1940, and its unique ARC identifier is 1097553.

Killingsworth's file consists primarily of the multipage investigation. There is ample testimony from witnesses and a good description of the events. Of particular note are two documents that record his physical condition, including a detailed description of the injuries he received. Killingsworth's file is part of Official Reports of Injury, 1937–1940, Preliminary Inventory 11, and its unique ARC identifier is 1097537.

The files for Wigand and Wigger are much smaller. That is usually the case for an accident that resulted in injury but not death. Nevertheless, there is valuable information among the records. There is always a good description of the accident and how long the enrollee was incapacitated. The documents list the enrollee's age and often his birth date. Permanent residences are often in the records, and the documents can include parents' names, which help piece together an enrollee's life. Wigand's file, for example, informs the reader that although he was serving in Arizona, his mother, Mary Wigand, resided in McKeesport, Pennsylvania. Wigand's and Wigger's files are both part of Reports of Accidents and Injuries, 1933–1942. The unique ARC identifier for Wigand's file is 1086610; the ARC identifier for Wigger's file is 1086611.

Finding the Files

There are approximately 7,600 accident reports among these two records series. Determining if there is a file for someone among the records is easy. The staff of the National Archives created a file list for all of these records. That list is searchable by name on Archives.gov by searching ARC or using the Online Public Access (OPA) search engine. You do not need to know the series in which the report is filed; ARC and OPA search both series. If you get a positive result for your name search, you should record the ARC identifier number (located under the person's name).

The index has one drawback. Because the CCC filed the reports by the name of the person who had the accident, you can easily find names of the primary subject but not the names of witnesses or other key players. In the case of Roaden's accident, for example, you can search for Roaden's name but not for Williams, Brock, Bowling, or any of the other names in the file.

Except for the five case files discussed in this article, none of the other accident reports are available online or on microfilm. They exist only in textual format and are housed at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland. As the case studies presented above illustrate, the CCC's accident files can provide an amazing picture of a person's life, and it is well worth a couple of minutes to do an online search for a file.

Kenneth Heger is a senior supervisory archivist at the National Archives, where he manages archival operations in Washington, D.C.'s Special Media Division and NARA's facilities in Chicago, Denver, Fort Worth, and Kansas City. He has a Ph.D. in history from the University of Maryland. He has published articles in numerous state and regional genealogical and historical publications and has made presentations on federal records to local, state, regional, and national organizations.