A Tower in Nebraska

How FDR Found Inspiration for the Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland

Winter 2009, Vol. 41, No. 4

By Raymond P. Schmidt

FDR designed a retreat for his Hyde Park property and unabashedly signed the drawings "Franklin D. Roosevelt Architect."

During his political career he had a hand in determining the appearance and location of many public projects, ranging from the World War I "temporary" buildings on the National Mall in Washington, DC, to the World War II Pentagon. He also played a major role in the construction of the National Archives Building along the Mall.

Nowhere was his role more transparent, however, than his part in building the Naval Hospital in Bethesda, Maryland—now commonly referred to as the National Naval Medical Center, or NNMC. Curiously, a brief stop during his 1936 reelection campaign at a unique new state capitol completed four years earlier inspired its design.

The Nebraska Capitol—Origins of an Architectural Inspiration

Nebraska Governor Robert Cochran unknowingly set the stage with an invitation for the President to "make the address of dedication" for the new state capitol in Lincoln. Cochran noted that the dedication ceremony would "mean perhaps more to all of our people than any other event which could take place." FDR’s presence, he insisted, would "draw a tremendous crowd . . . from adjacent states as well." FDR agreed to deliver the requested speech during his October railroad swing across several Plains states.

As FDR's special train crossed the Missouri River border from Iowa into Plattsmouth, Nebraska, on October 10, 1936, he was aware of the powerful economic and political symbolism of the new Nebraska capitol. New York architect Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue had won the competition in 1920 with a tradition-breaking "American Modernist" design of a "cross within a square" dominated by an occupied tower 400 feet high. The four interior courtyards surround a central rotunda, and the dome supports a statue of a sower 19½ feet tall standing on a 12½-foot pedestal of wheat and corn motifs.

Goodhue skillfully overcame a scheduling challenge: Erect the tower and its wide, low surrounding base around the sagging existing capitol, moving employees into the new capitol in stages. State officials achieved a similar feat in paying for the entire $10 million cost of construction, furnishings, and landscaping in full when the new building was completed, as the Great Depression swept across the country.

Uniting for Victory—Blurring Party Lines in an Election Year

When Roosevelt addressed his supporters in Plattsmouth around noon on that Saturday in October, he told a crowd of 4,000 to 5,000 that he had "brought the best part of Nebraska into Nebraska with me." This reference to Senator George W. Norris, reported in Lincoln's Evening State Journal, paid tribute to one of FDR's staunchest allies in Congress.

The four-term Nebraska senator was widely known as "father of the TVA," the Tennessee Valley Authority, shepherding that signature New Deal legislation through Congress in 1933. Norris had previously co-sponsored the Norris-LaGuardia Act of 1932 that outlawed so-called "yellow-dog" contracts prohibiting employees from joining a labor union. More recently, he had moved the Rural Electrification Act toward passage in May 1936.

George Norris began his political career in 1902 as a traditional Republican congressman but then earned election as a Progressive Republican senator in 1912. In 1928 he supported Democrat Al Smith and in 1932 Franklin D. Roosevelt for President—thereby earning a reputation among some Republicans as one of the "sons of the wild jackass."

In the 1936 election, however, the 75-year-old politician abandoned his party entirely and reluctantly ran again, this time as an independent. The New Deal President was obviously drawn to Nebraska to endorse Norris for reelection to a fifth term in the United States Senate. Both were to gain victories from their cross-party support.

Facing the Voters . . . and the Nebraska Capitol

When FDR delivered his "dedication" speech in Lincoln two hours after crossing the river, his raised platform faced the principal entrance on the north capitol front. This elevated perch allowed him an unobstructed view of the entire building, where he could take in the impressive tower topped at its dome by a bronze statue, the broad three-story base, the steps and streets clogged with tens of thousands of cheering voters, and the grassy terraces that held friendly throngs of thousands more.

"It was the first time since the capitol was built that [the capitol front was] . . . ever covered with humanity, and it was a grand sight," reported the Lincoln Sunday Journal and Star the next day. This warm reception left an indelible impression on FDR. He praised the capitol as "a great and worthy structure, worthy of a great state." His characterization of the building as "this wonderful structure" that "all the people of America . . . ought to come here and see" carried more weight than anyone at the time could realize.

Design Approval and Site Selection for a New Naval Hospital

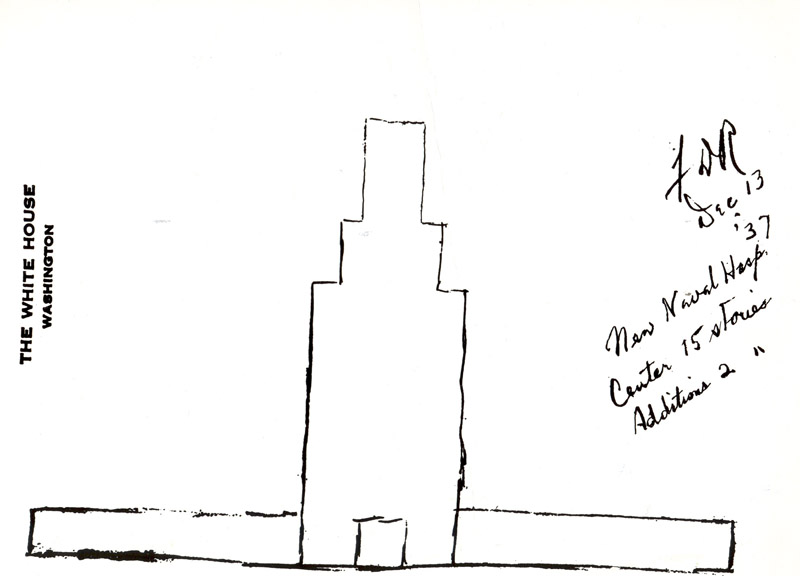

The tower image obviously remained vivid in FDR's memory. Even as the President engaged in bitter public disputes throughout the late 1930s over his preferred Pantheon-design for the Jefferson Memorial on the Tidal Basin, he also prevailed over strong but much less publicized opposition to his personal design for a long-awaited new naval hospital in the Washington area. When Congress approved funding for it in 1937, FDR knew exactly what he wanted. In December, he drew a line sketch for a two-story base supporting a 15-story tower.

The Navy Bureau of Yards and Docks published preliminary drawings seven months later, only to be met with opposition from the National Park and Planning Commission (NPPC) and the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts (CFA).

Frederic Delano, FDR's uncle and his hand-picked president of the NPPC, pointed out that the tower exceeded the 130-foot height ceiling for buildings in the District of Columbia that was established by law. Gilmore Clarke of the CFA agreed and objected to the "modern block design" of the hospital. When revised plans later that fall showed a four-story base and a tower 250 feet, or 23 stories, high, opponents envisioned an architectural nightmare, especially if it rested on top of the hill at 23rd and E Streets where the existing Naval Hospital stood. Despite this resistance and attempts by opponents to deny him the funds, in the end FDR got his tower.

Not content just to design the hospital, FDR also insisted on selecting its site. He wisely rejected constructing it on the site of the existing Naval Hospital, a few blocks north of the Lincoln Memorial. This would have unleashed another, more justifiable, storm of criticism.

Some 80 sites in Maryland, the District, and Virginia were proposed as the favored location. Instead, in July of 1938 FDR motored to a bucolic setting along Rockville Pike in the then-small village of Bethesda, Maryland—several miles north of the District and directly across the road from the new National Institutes of Health.

The presidential car paused on a grassy knoll west of dense woodlands. FDR reached over the side of his open touring car and touched the ground with his cane, announcing "We will build it here."

For FDR, the tower conjured a scene similar to the pastoral English countryside with "fairly high church towers . . . sticking up above the trees and other buildings." He instructed that the hospital grounds be "treated romantically, like a sheep field, . . . [and] ordered their enclosure by a sheep fence."

Preserving FDR's Vision

Roosevelt presided over laying the cornerstone on November 11, 1940, and dedicated his hospital on August 31, 1942. Expansions completed in 1963 and 1980 added new hospital wards, other medical facilities, and parking garages. In 1977 the tower received protection by being listed in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). Throughout the decades, FDR's tower continued to dominate the site.

The campus is undergoing major changes in this new century, however. Terrorist attacks in the United States on September 11, 2001, caused the erection of a security perimeter and removal of the "sheep fences." Base Realignment and Closure recommendations resulted in a 2005 law that closes the Walter Reed Army Medical Center in northwest Washington, DC, and consolidates major Army clinics and wards at the NNMC. The expanded, new joint hospital will bear the title Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, and is on track to become operational in September 2011.

Although the new medical facility will respect the tower's NRHP historic designation, new construction and renovation are forever altering the appearance of the NNMC campus. FDR most certainly would have taken a keen interest in assuring that his vision of a tower "rising above the trees" in a calming pastoral setting continues to further the practice of the healing arts in aptly named Bethesda.

For more on FDR and his architecture, learn about the Hyde Park school he also helped design.

Capt. Raymond P. Schmidt, USNR (ret.), is a Nebraska native who earned bachelor's and master's degrees from the Universities of Nebraska and Wisconsin, respectively. He served 14 years as the first civilian cryptologic historian of the U.S. Navy and has authored and edited numerous published articles. His son was born in the Bethesda Hospital Tower, and he personally witnessed these changes to the NNMC over the past five decades.

Note on Sources

Bethesda has long been associated with healing. It is the name given to a series of pools in Jerusalem and has linguistic as well as Biblical roots. Some sources claim the name derives from the Aramaic beth hesda meaning house of mercy or house of grace. References to a similar name can be found in the Gospel of John, possibly pertaining to a pool for sheep or, alternatively, a pool located near a sheep gate in the city wall.

Governor Robert Cochran's invitation to FDR to speak at the state capitol dedication (letter of July 14, 1936); FDR's response of July 21, 1936; and "Remarks of the President at the State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebraska," October 10, 1936, are in the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, New York.

For an examination of FDR's close interest in architecture, see William B. Rhoads, "Franklin D. Roosevelt and Washington Architecture," Records of the Columbia Historical Society 52 (1989): 104–162. Additional information on FDR and the naval hospital is from E. Caylor Bowen, editor of Transplantation Research Program Center, Naval Medical Research Institute, Naval Medical Command, National Capital Region, "Naval Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland (1939–1984)" (unpublished manuscript).

The description, dimensions, and cost of the Nebraska state capitol are from the Nebraska Blue Book, State Capitol Information Office. Goodhue's design was the third state capitol. The first two buildings were constructed in 1867 and 1889, respectively. Frederick C. Luebke, Nebraska: An Illustrated History (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995) contains useful information about the Nebraska capitol, including a discussion of a formal dedication in 1967.

Information on Senator Norris may be found in Richard Lowitt, George W. Norris: The Triumph of a Progressive, 1933–1944 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978). This is Lowitt's third volume of this comprehensive biography. The first two volumes cover 1861–1912 and 1913–1933, respectively, of Norris's remarkable life and political career. Norris was the first candidate in Nebraska history to win a senatorial election as an independent. It is not a coincidence that Nebraskans followed his lead in adopting a nonpartisan unicameral legislature by amending its constitution in 1934.