DOCUMERICA

Snapshots of Crisis and Cure in the 1970s

Spring 2009, vol. 41, no. 1

By C. Jerry Simmons

By the late 1960s, the American landscape was ravaged by decades of unchecked land development, blighted by urban decay in the big cities, and plagued by seemingly unstoppable air, noise, and water pollution. In November 1971, the newly created Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced a monumental photodocumentary project to record changes in the American environment. DOCUMERICA resulted in a collection of more than 20,000 photographs by its conclusion in 1978.

The project takes rightful credit for the United States’ first serious examination of its rapidly decaying natural environment. With Gifford D. Hampshire as project director, and with a clear mission to "pictorially document the environmental movement in America during this decade," photography started in January 1972.

As expected with any large-scale, nationwide project, Hampshire and other DOCUMERICA organizers saw their fair share of problems and challenges, ranging from copyright arguments with the American Society of Magazine Photographers to the salaries of individual photographers. At one point, the project was nearly scrubbed by EPA’s managers as it had become too complicated for the young agency to manage. After an administrative reorganization in August 1972, and an infusion of photodocumentary expertise from Arthur Rothstein, former Farm Security Administration photographer, DOCUMERICA took on a life of its own and became a hit among Americans who had seen just a sampling of the photographs in exhibits staged at EPA facilities and other small venues.

Now, more than 30 years since the dismantling of the last exhibit, DOCUMERICA photographs bridge a span of three decades of environmental revolution in the United States. DOCUMERICA’s official mission effectively focused on popular but valid environmental concerns of the early 1970s: water, air, and noise pollution; unchecked urbanization; poverty; environmental impact on public health; and youth culture of the day. But in reaction to the varied pollution, health and social crises, DOCUMERICA succeeded also in affirming America’s commitment to solving these problems by capturing positive images of human life and Americans’ reactions, responses, and resourcefulness.

Gifford Hampshire, DOCUMERICA Project Director

Under Gifford Hampshire’s expert direction, the DOCUMERICA photographers contributed a collective snapshot of the American environmental crisis, focusing on a set of guidelines developed by Hampshire and the EPA administration. A World War II veteran, photojournalist, and selftaught student of documentary photography, Hampshire found himself working for the first EPA administrator, William D. Ruckelshaus, in 1971, and soon after became the director of DOCUMERICA. Ruckelshaus remembers Hampshire as an "interesting fellow" who was energetic about depicting environmental issues using toprate photographers and photographs.

In his own words, Hampshire describes his inspiration for ideas that soon became DOCUMERICA.

"It was an exciting time. The public was expecting results." Hampshire remembered in his 1997 memoir. EPA had worked swiftly to close down the big offenders of industrial pollution, but industry was only one source of the problem. It became clear that on many fronts, ordinary people were responsible for many pollution issues: "fouling our own nest—we were the easy-come easy-go society, the throw away society, the society that was dependent on convenience goods without regard to its cost to our only world."

Using a clear set of guidelines and mission points inspired by Rex Tugwell’s and Roy Stryker’s Farm Security Administration (FSA) project of the 1930s, Hampshire and his hand-picked photographers systematically recorded the ills of the 1970s American landscape, and the resulting photographs colorfully and explicitly illustrate the breadth of the nation’s problems and struggles with noise, water and air pollution, health problems, and social decay. FSA photographer Arthur Rothstein personally assisted Hampshire in hiring some of the photographers.

The energy and excitement for DOCUMERICA began to fade after Ruckelshaus’s departure from EPA for the directorship of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and Hampshire recalled in his memoir how "my enemies attacked me and DOCUMERICA." He cited the 1974 recession, major cutbacks, and political, industry pressures on EPA’s leadership as the beginning of the end, and that his own health issues depleted his energy for DOCUMERICA over the next several years. By the time he returned to work after heart surgery in 1978, "There was no sense of purpose, no fireinthebelly," Hampshire lamented, and that after much initial celebration and publicity in the early stages, "DOCUMERICA was just a file now." He worked at EPA until 1980, when he retired from government service.

Documenting America’s Nationwide Crisis

Simply put, DOCUMERICA was geographic in nature, and each photographer worked in one area of the United States, in many cases the general area where they lived and where many had already been working as professional photojournalists. EPA purchase orders for each photographer detailed the geographic areas to cover and occasionally mentioned specific subject matter of particular interest to EPA and Hampshire. In January 1972, Hampshire started the new year by issuing the first in a series of "Guidelines for Photographers," the first of which served as a working outline for the small group of initial DOCUMERICA photographers, several of whom were recruited by Hampshire from contacts at the American Society of Magazine Photographers and the National Geographic magazine and from those who had worked for the Farm Security Administration’s photodocumentary project during the Great Depression.

The project’s geographic approach created a working map with specific environmental problems or issues concentrated in certain areas. For example, photographer Michael Philip Manheim worked in his hometown of Boston, where he took dramatic photographs of a noise pollution crisis in the Neptune Road neighborhood near Logan Airport’s main runway in East Boston. The effects of excessive jet engine noise caused serious physical and mental stress for residents in the landing path. Manheim captured the severity of the problem with his frank images of low-flying 727 jets screeching over the rooftops of East Boston houses. For some Neptune Road dwellers, life simply went on, jets, construction, noise, and all. For others, the noise made Neptune Road unlivable, and relocation was the only choice. Once a vibrant neighborhood of iconic three-decker-style Boston homes, the Neptune Road of today is an industrial area occupied by self-storage warehouses, shipping companies, and construction vehicle lots servicing Logan Airport. The noise-plagued homes and residents of the Neptune Road neighborhood of the 1970s are now gone.

While Manheim illustrated the noise over Boston, photographer Jack Corn went underground in West Virginia and Tennessee, where he captured images of coal miners and their families coping with mining-related injuries and the dreaded black lung disease. Similarly, Bill Gillette documented a mining crisis in Colorado that eventually destroyed an entire town. His assignment was to photograph the results of unchecked exploitation of natural resources in the Colorado towns of Rico, Uravan, Durango, and Telluride. In Gillett’s opinion, the images of Uravan, a small mining town built and maintained almost entirely by the Union Carbide Company for uranium mining, speak most powerfully.

Gillette had a longtime personal fascination with mines and found miners and the lighting and mood in mines to be a driving force in his photography long before his DOCUMERICA work in 1972. As it turned out, Gillette had worked and lived near Uravan in the 1960s. While living in Nucla, Colorado, Gillette worked in a uranium mine at night and taught in a Nucla school during the day, teaching the children of his fellow miners. When he returned as a photographer to Uravan, he captured images of toxic seepage from several Union Carbide mine facilities close to homes, schools, and businesses and in the nearby San Miguel River. After years of damage from uranium residues, Uravan is now a ghost town; its entire population was moved out, and all buildings, except for two historic sites, were leveled by Union Carbide.

Documenting America’s Response

Out of crisis comes an opportunity for change, and while DOCUMERICA gathered images of loss and tragedy, it also collected images of Americans making a difference and creating positive change in their own lives and their surroundings. Among the thousands of DOCUMERICA photographs, David Hiser’s images of Michael Reynolds, a visionary architect and environmental activist, give testament to the American spirit of invention and ingenuity still going strong in the difficult years of the 1970s.

A former National Geographic magazine photographer, Hiser’s assignment was to document strange new homes in Taos, New Mexico—strange because they were built from discarded beer and beverage cans. Reynolds built his first "beer can house" in Taos in 1974, in a process that bundles cans in small sets and secures them in mortar, repurposing them as structural and insulating building materials—a resourceful repurposing of common materials as an inexpensive alternative to traditional concrete blocks, bricks, steel, and wood.

Where Hiser found repurposing of common refuse, Tom Hubbard found renewed interest in a city’s center at Cincinnati’s Fountain Square. A photojournalist with credits at several daily newspapers, Hubbard had been working for the Cincinnati Enquirer before starting his assignment with EPA. He learned about DOCUMERICA after seeing an exhibit of its early photographs. The images overwhelmed him, and he "lusted to be a part of it." He asked for a meeting with Gifford Hampshire in Chicago—a meeting where Hampshire rejected his initial ideas and proposals. After three hours of discussion, though, Hubbard and Hampshire settled on an examination of everyday life in Fountain Square.

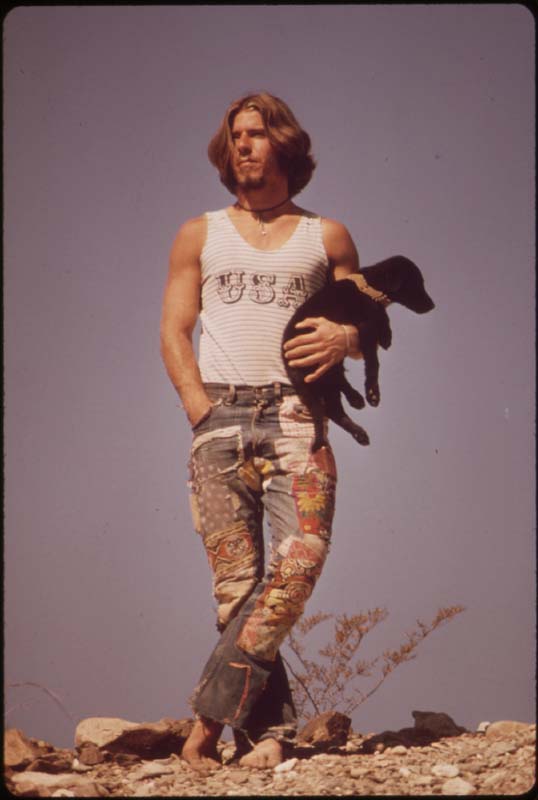

In Fountain Square in summer 1973, all facets and faces of American life passed before Hubbard’s lens. In keeping with Hampshire’s guidelines to get "photographic documentation of what the people of the nation do, or are, or think or feel," Hubbard snapped images of young backpackers in bell-bottom jeans stopping in the square on their backpacking trek; everyday people wearing the fashion of the times and enjoying popular music; and peace-sign balloons in the cab of a pickup truck, serving as a silent but familiar protest message against the Vietnam War. Hubbard’s photographs of everyday folks enjoying music, dancing, and socializing in the square fit well into Hampshire's edict to document Americans just "doing their thing." The images capture a freeze-frame of early 1970s attitudes toward public behavior, fashion, and cries for peace. Fountain Square, like other public spaces in urban centers, declined in popularity during the late 1980s and early 1990s, becoming a location to be avoided. After a revitalization project in 2006, the square recovered its reputation as a symbol of civic pride, and it continues to be a significant landmark at the heart of Cincinnati’s public life and catalyst for the downtown’s rebirth in recent years.

Balancing the unfortunate reality of black lung in the West Virginia and Tennessee coal mines, the photographs of Charles O’ Rear show us the healthy and happy face of what was documented as the healthiest place in the United States in the early 1970s. Hampshire had learned of a place in southeastern Nebraska, from Colfax to Jefferson counties, where middleaged white males had consistently shown the lowest death rates in the entire nation. He was intrigued, and he wanted O’ Rear to uncover the story.

While studies into the phenomena made no strong conclusions to explain the healthy Nebraskans, most experts believed that factors including physical environment, water quality, atmosphere, food, and the agrarian lifestyle had most to do with the healthy Nebraskans. The result of O’ Rear’s work in Nebraska became a lasting snapshot of Midwest America.

DOCUMERICA on Exhibit

As DOCUMERICA photographers submitted their initial work, it became clear that the images should be shared with the American public sooner rather than later, and the decision was made early on to exhibit the photographs. In August 1972 the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., displayed 155 photographs for six weeks in a small exhibit titled "DOCUMERICA 1." This inaugural exhibit featured the work of only 23 of the nearly 100 DOCUMERICA photographers and highlighted only subjects covered by the project to date, basically images from the southern, southwestern, and west coast regions of the United States.

Although the Corcoran exhibit was the first publicized display, it was not the first time the American public had a chance to view the photographs. Before the Corcoran exhibit, Hampshire sent an exhibit of a small, thematically arranged set of photographs to a few select U.S. cities, including New Orleans, Cincinnati, Dallas, and Philadelphia. Hampshire soon realized that he could not be in the business of managing the project and overseeing the traveling exhibits, so he sought to turn over the exhibition responsibility to the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service (SITES). The result of SITES involvement was the exhibit titled "Our Only World" at the EPA’s Visitors Center, opened with a ceremony attended by then EPA Administrator Russell E. Train and Smithsonian Secretary S. Dillon Ripley.

As DOCUMERICA closed, so did the traveling exhibits. EPA and Smithsonian records indicate that the extended tour of several copies of the "Our Only World" came to a successful conclusion in August 1978. Other records tell of how six duplicate copies of the traveling exhibit found homes with various educational institutions, among them the Neville Public Museum in Green Bay, Wisconsin, and Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas.

Conclusion

When we look at images of today’s environment, we can see that what troubles the environment in the new millennium is what troubled it in the early 1970s, and DOCUMERICA confirms it. Thousands of images of pollution, strip mining, crowded cities, and land abuse could well be photographs taken in recent times. Though a great deal has been done over the past 30 years to correct problems depicted in the photographs, there is a common consensus that there is so much left to accomplish in the race to save America’s natural resources. The color images from the 1970s show us that Americans must keep lenses sharply focused until environmental solutions are realized. Project DOCUMERICA images serve to inform and inspire Americans as we pursue the green revolution of the new millennium.

How to find DOCUMERICA photographs at the National Archives

After DOCUMERICA’s demise in 1978, Hampshire shipped the entire file to the Center for Creative Photography (CCP) in Tucson, Arizona. The center accepted the file and made the photographs available to researchers. In 1981, however, in compliance with laws governing the disposition of federal government records, the DOCUMERICA collection moved to the National Archives and was formally accessioned in April 1981. The thousands of images can be found in the Still Pictures unit at the National Archives at College Park, Maryland. The descriptions of DOCUMERICA photographic prints, slides, images on fiche, and related textual documentation are searchable in the National Archives Catalog. The 15,981 DOCUMERICA images are available online and are also searchable via ARC. Researchers can also visit special web pages dedicated to environmental studies at the Documerica section.

C. Jerry Simmons, a gradate of the Catholic University of America’s School of Library and Information Science, is an archives specialist for data standards at the National Archives and Records Administration in College Park, Maryland, and has worked with the National Archives Catalog project since 2000.

Note on Sources

Not all DOCUMERICA images are represented in the National Archives Catalog. Series RG-412-DM (ca. 5,000 color slides) and RG-412-DAZ (ca. 500 slides) are images taken during the final phase of DOCUMERICA. These late submissions were not included in the official project to digitally convert images and captions from DOCUMERICA microfiches in the late 1990s. The images in these two series contain very probing studies done during DOCUMERICA including Yoichi Okamoto’s photographs of suburban life near Washington, D.C., adding important dimensions to the DOCUMERICA record.

Sources for this article include Environmental Protection Agency records (Record Group 412) held at the Still Pictures unit of the National Archives at College Park, Maryland; records from the Corcoran Gallery of Art Archives; the personal memoirs of Gifford D. Hampshire; archival materials from the Center for Creative Photography (Tucson, Arizona); and interviews with former DOCUMERICA photographers, the Gifford D. Hampshire family, and former EPA administrators Bill Ruckelshaus and Russell Train. Still Pictures archivists Nick Natanson and Billy Wade provided information about the management of DOCUMERICA images.