Independence and the Opening of the West

Harry S. Truman, Thomas Hart Benton, and the Making of the Mural

Spring 2009, vol. 41, no. 1

By Raymond H. Geselbracht

The construction of the Harry S. Truman Library in Independence, Missouri, was in its final phase by the spring of 1957. The front portico was largely finished, and one could imagine walking up the grand stairway to the front doors, entering, and standing in the spacious entrance lobby. An auditorium would be to the left, the Oval Office replica straight ahead, and the two main museum rooms to the right. The auditorium would one day be the venue for speeches, conferences, films, and other public programs; the Oval Office replica would fascinate almost everyone; and the museum rooms would feature exhibits on the presidency and American history.

But what would the big entrance lobby, the place where visitors would get their first impression of the interior of the Truman Library, be like? Would it be nothing but a cold, institutional, echoing space, with a high ceiling, an expanse of empty wall, a bit of grayish marble trim, and hard vinyl flooring? It would certainly be big enough to handle the large numbers of visitors expected to come to the Truman Library, but would it make them feel welcome, and would it in some way begin the educational experience that former President Truman wanted his library to provide?

David Lloyd, the executive director of the Harry S. Truman Library, Inc., which raised the money to build the library, had an idea how to make the lobby both attractive and educating. He knew of a great Missouri artist, Thomas Hart Benton, who lived in Kansas City. Benton was an old man now, his style of art was out of favor, but he was still vigorous and active. Museums and art galleries were not interested in his work, and it sold poorly. But he was still well known as a mural painter. It was this aspect of his work that captured David Lloyd’s interest. He wanted the Truman Library corporation to commission Benton to paint a mural in the library’s lobby.

In some important ways, Benton was a perfect choice to paint a mural for the library. He was Missouri’s greatest living artist; his style was more or less realistic and accessible to ordinary people; and his murals were usually on historic subjects. He worked on his murals as if he were a historian, discovering and revitalizing past people and events. Lloyd probably knew that this commitment to history would strongly recommend Benton to someone who loved history as much as former President Truman did.

But bringing Harry Truman and Thomas Hart Benton together would be more difficult than Lloyd suspected. They had already met twice, and there was something wrong about their slim relationship. Their first meeting was at the White House on February 24, 1949. Truman had just finished a press conference. When Benton was introduced to him, Truman said in a bantering way but with a stern look in his eyes, "Are you still painting those controversial pictures?" Truman did not laugh when Benton replied, "When I get a chance." Benton left that first meeting feeling that Truman did not quite approve of him.

Their second meeting occurred in 1955, at a dinner party at the home of Randall Jessee, a prominent television newscaster in Kansas City. During the dinner conversation, Benton said some very favorable things about Truman’s accomplishments as President. Afterwards, someone asked Truman how he felt about Benton’s famous mural of the 1930s, A Social History of Missouri , in the Missouri State Capitol. Truman surprised everyone by showing annoyance at the question. Something about this mural was clearly distasteful to him. Later, in private conversation with his host, Truman said of Benton, "I don’t know whether I like that fellow or not. You know . . . I have a long memory." Truman was apparently troubled that he had been unable to hide his private feelings about Benton’s work. Not long after the night of the dinner party, he wrote his daughter, Margaret, about his conflicted feelings. "It seems that Tom Benton thinks your pa is a top-notch president. It made me ashamed of my opinion of him as a mural painter." When Benton later learned about Truman’s comment from Randall Jessee, he didn’t know what Truman could be referring to.

Lloyd was probably unaware of this slight but problematic relationship between Truman and Benton when he made his first visit to Benton’s Kansas City studio in April 1957. Wayne Grover, the Archivist of the United States, went with him. Grover headed the National Archives and Records Service, which would run the Truman Library once it was donated to the government by the Truman Library corporation. He took a strong personal interest in the new library and, like Lloyd, thought a mural would enhance the lobby. Benton showed Lloyd and Grover his current mural project, which was about the early history of Canada. After their short tour, Lloyd and Grover asked if Benton would be interested in painting a mural for the Truman Library. He said he would.

About a month later, Lloyd and Grover came again to Benton’s studio, and this time they brought Truman with them. Unfortunately, the first thing Truman saw as he entered the artist’s studio was a panel of the Canadian mural that showed an almost naked Seneca Indian, life-size and, as Benton later remembered, "almost as real as life itself." Truman, Benton remembered, "stepped back as if something had hit him" and turned his back on what was for his gentle, old-fashioned soul a display of too much rosy flesh. The mural’s second panel, which Truman now encountered, was much better. It featured French explorer Jacques Cartier planting a banner to claim Canada for France. This panel took Truman’s interest, and he and Benton got into a conversation about what emblems should be on the banner Cartier used to claim Canada. After some learned conversation of this kind, Truman said, "I never knew that artists could be so careful about historical facts." Benton replied, "Mr. President, when I am commissioned to paint a piece of history I take the trouble to know it."

David Lloyd saw that the time was right to bring up his idea for a mural at the Truman Library. He suggested to Truman that it could be about the history of Independence, and said he thought such a mural would be very attractive to the library’s visitors. Truman agreed. The idea interested him, but he wouldn’t commit himself. He said he needed time to think about it. This ended the conversation and, unfortunately, when Truman turned to leave the studio, he encountered the Seneca Indian again. Once again he had to avert his embarrassed old eyes to avoid seeing too much of it.

Not long after this, Truman asked Benton to visit him at the Truman Library. Benton came, and Truman greeted him very cordially and took him to the library’s lobby to show him the wall proposed for the mural. Truman asked how much a mural would cost. Benton roughly estimated the size of the wall, which was about 19 feet high and 32 feet wide, considered the amount of research he would have to do to make the mural historically accurate, and said the mural would cost $60,000. Truman appeared relieved that Benton had not asked for more. He said the library foundation could afford $60,000, but still he made no firm commitment. Weeks went by, and still Benton heard nothing from Truman. Finally, David Lloyd admitted to Benton that he had not been able to get Truman even to talk about the mural project. Benton wanted this project, and he told Lloyd that he was pricing it low, which he did not mind doing, because "the idea [of the Truman Library mural] interests me and there is a kind of honor involved also. I fully appreciate this latter."

Benton decided to try to discover what Truman’s "long memory" comment of two years earlier might refer to. He went to Randall Jessee for help, and he learned that the problem related to the presence of Kansas City political boss Tom Pendergast in the Social History of Missouri mural. Truman, who never forgot that Pendergast gave him his start in politics, thought Benton had put him in the mural against his will. Benton was very surprised. Not only had Pendergast wanted to be in the mural, he had allowed Benton to sketch him. Jessee apparently got this explanation to Truman, who seemed to give up his mistaken idea.

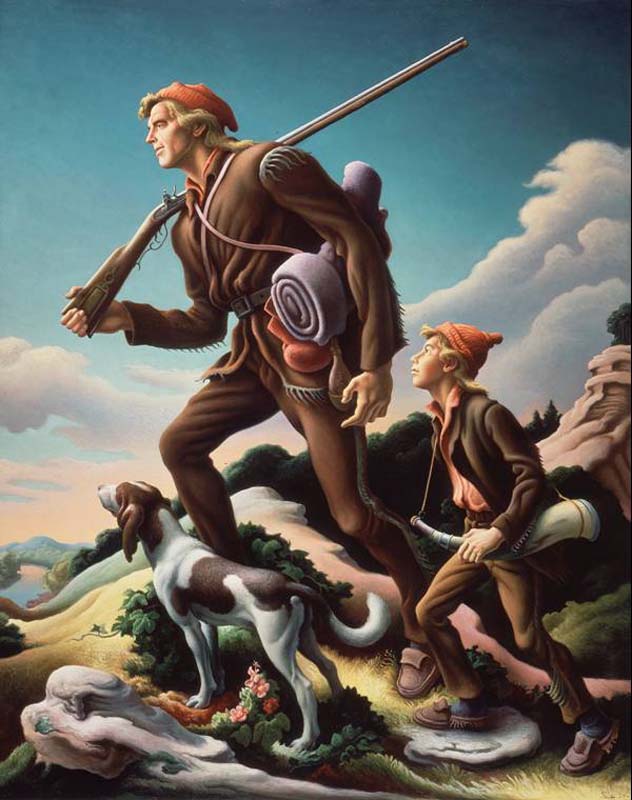

Benton thought Truman also had some general grievance concerning his art, and he was right. It’s possible Truman disliked every painting and mural of Benton’s he had ever seen. He definitely disliked one of Benton’s recent works, a painting called The Kentuckian. This was a painting done for a motion picture of the same name, which was produced in 1955. In late 1954, one of the film’s producers asked Truman to pose with Benton in front of this painting, which showed the film’s namesake, The Kentuckian, modeled on its star, Burt Lancaster. Truman wouldn’t do it. He had seen a photograph of the painting and he didn’t like it. He explained why in a letter to the producer. "I don’t like Mr. Benton’s Kentuckian. It looks like no resident or emigrant from that great State that I’ve ever seen. Both of my grandfathers were from Kentucky as were both of my grandmothers. . . . They did not look like that long necked monstrosity of Mr. Thomas Hart Benton’s." This was a bit strong, and Truman decided not to mail the letter. But it expressed how he felt about Benton’s art.

Truman’s reservations about Benton were gradually overcome by the comfortable familiarity and sense of what Benton referred to as "psychological kinship" that developed between the two men as they got to know each other better. Not long after Benton’s first visit to the Truman Library, Truman asked him to come again. The first time Truman had taken Benton on a tour of the library; this time he took him into his office and offered him bourbon. The stiff drink helped Benton fight off a feeling of intimidation as he sat across from a man who had once exercised all the great powers of the presidency. He gradually came to understand what kind of person Truman was. "Beneath the rather formidable Presidential aura," he later wrote, "there was a simple, straightforward, essentially friendly man, without an iota of pretentiousness in his makeup." In the course of the conversation, Benton started talking about his ideas for a mural. He wanted it to be about the history of Independence and the westward movement across the Oregon and Santa Fe trails. "It was at this moment that the theme for the Truman Library mural was born," he later recalled.

There was still no formal understanding between Truman and Benton about a Truman Library mural. But Truman invited Benton back to the library several more times, and each time the two men sat together in Truman’s office and shared some friendly conversation and a glass of bourbon. Benton one day felt so free and casual that he asked for a second glass. "Tom," Truman answered, "you’re driving a car. You can’t have another [glass] because you’ve got too much work to do around here. I’m not going to take risks with you." Benton knew when he heard this that he would get the job.

Several more meetings followed at which Truman and Benton discussed the theme of the mural. Truman had some doubts about centering the mural on the history of Independence, mainly because of the people, including himself, who might have to go into such a painting. He was adamant about not wanting to be in the mural. Benton knew that David Lloyd and all the donors to the mural project expected that Truman would be in the mural. But Truman wouldn’t allow it. "I admired him for it," Benton admitted.

Benton was dismayed at some of the ideas Truman wanted him to consider in place of the Independence theme. For a time, Truman insisted the mural be about Thomas Jefferson and Jeffersonian democracy. Benton was appalled and said he could not paint something so abstract as democracy. Then Truman suggested the mural be about Jefferson and the Louisiana Purchase. "Put your mind on that, Tom," he said. Benton began to worry there was no wall in the Truman Library big enough to hold all the history that Truman wanted included in the mural.

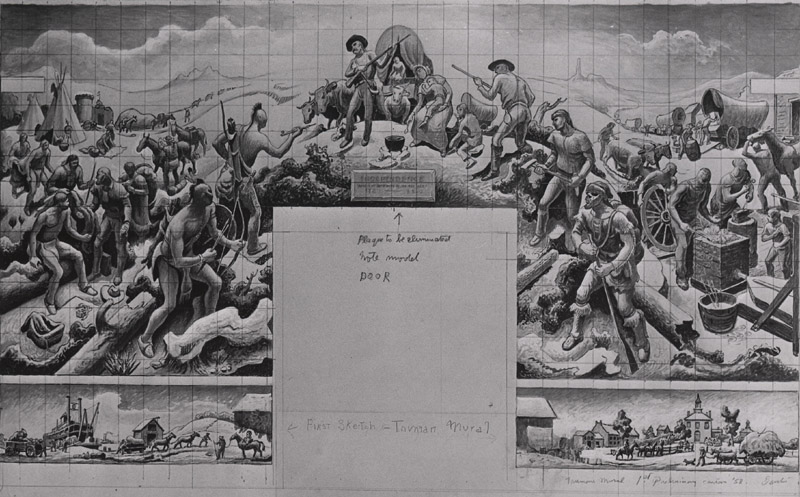

Finally, Benton wrote up his ideas for the Independence theme. Truman read the memorandum and seemed receptive, but he still had some questions. Benton redrafted his memorandum and also made a clay model, about four feet long and two feet high, of his plan for the mural and took it to the Truman Library for Truman to see. He set it up in the reception area outside Truman’s office. Truman had some people with him, and he brought them out to see the model. Benton explained a few features of the plan, and then Truman took over, elaborating on the history which the mural presented. Benton could tell that Truman, right there and then, was making the plan his own. The mural would be about Independence and the opening of the west.

A few days later, on June 6, 1958, Truman asked Benton to have lunch with him in Kansas City. When Benton arrived, Truman held up two sheets of paper. "Here it is, Tom," he said. It was the contract. Benton was eager to see how it was worded, but Truman held him off for a time with light-hearted talk as he went through the contract and explained the terms himself. Benton was satisfied and he signed it. The Harry S. Truman Library, Inc., put out a press release about the mural project that said "President [Truman] is to have final approval of the subject matter and design." Benton knew, though, that the problem of patron interference was over with. "I had control of the job," he later recalled.

Benton was already well into his work of researching the mural theme by the time he signed the contract. He had learned long ago, when he was a young artist in New York and Paris, that he didn’t want to paint solely from his imagination. He wanted to paint realistic themes, often on historical subjects, that a wide public would like and appreciate. He developed a style that one critic called "semi-expressionist quasi-folksy realism," which was well suited to the kind of public art that he wanted to create.

A realistic art intended for everyone had to be historically accurate, and this required extended research. All the details had to be right—landscapes, facial types, costumes, tools, weapons, wagons, buildings. Benton knew he would hear about it if he made a mistake. "If I make a tiny error in an Indian’s headdress . . . or a rifle," he said while in engaged in his research work for the Truman Library mural, "people come down on me like a ton of bricks. They never criticize the artistic quality one way or another, but the historical detail must be absolutely accurate." He also learned that every figure in a painting or mural had to be based on a living model. "You must draw from life," he said, "or you wind up with generalized illustrations, or you more or less draw yourself in every figure."

He began his research for the mural by reading about the history of Independence and the westward movement. Then, in the spring of 1958, he spent three weeks traveling to museums and libraries in Missouri, Colorado, and Oklahoma, making sketches of costumes, tools, weapons, and other objects he might want to use. He then made his first detailed sketch, called a cartoon, of his mural design, and he made a new sculptural model—which he did following the practice of the muralists of the Renaissance, who wanted their murals, as he wanted his, to have a sculptural depth, a sense of a third dimension. He always kept the sculptural model nearby when he painted a mural.

Having refined the mural design during the summer and fall of 1958, Benton wrote a new draft of his memorandum about the mural, which he titled "Mural Project: Independence and the Opening of the West." He shared the memorandum with Truman, who was completely satisfied with what he read and saw of Benton’s plans. On December 1, 1958, Truman sent a letter to David Lloyd about his meetings with Benton. "I believe we worked everything out to the complete satisfaction of both of us," he wrote.

In May 1959, Benton set out on a research trip that would take him to Oklahoma, Colorado, and Nebraska. Although he visited some museums to sketch costumes, arms, and implements that would appear in the mural, his primary interest on this trip was in the landscape itself and the Native Americans who still lived in or near their original homelands. His reading told him that settlers leaving for the west from Independence might have met first with Pawnee Indians as they crossed into Kansas territory. On the left, or western, side of the mural, he planned to feature a seven-foot-high Pawnee warrior, and he wanted to base that figure on a model with features that were historically correct. Guided by his friend and fellow artist Charles Banks Wilson , who knew where to find models of the kind Benton needed, he went to Pawnee, Oklahoma, and waited outside a church while people came out from a revival service. One of the preachers was among the first group of people to come out of the church. He was exactly right. His name was Floyd Moses, and he was Pawnee. After a little discussion, Benton took Moses to a schoolroom in the church and made sketches of him in the pose of the Pawnee warrior in the mural plan.

Having found a model for this important figure, Benton next went in search of a model for a Cheyenne trader figure, which would be placed to the left, or west, of the Pawnee warrior. In Canton, Oklahoma, he found a tall, deeply lined old man, named John Hoof, who was just right. Benton sketched him sitting in the pose of the Cheyenne trader. There were several other good models in Canton, and Benton sketched their faces. He also found a model for a Cheyenne woman in a nearby town, and he made sketches of her.

He then headed for Colorado to visit places and see sights that would have been familiar to travelers along the Santa Fe Trail in the 1840s. He found the ruins of Bent’ s Fort in southeastern Colorado and, after walking for about two hours to find the right vantage point, sketched the nearby Spanish Peaks. He imagined himself on the Santa Fe Trail a hundred years earlier and looked through old eyes at a landscape not much changed by the passage of time. He made sketches of what he saw and included some flora that he wanted to include in the mural. Then he drove to Denver to examine artifacts in a museum collection, and then to Nebraska to visit and sketch two famous landmarks along the Oregon Trail—Chimney Rock and Courthouse Rock.

Benton found models for some of his figures close to home in Kansas City. His friend and neighbor Randall Jessee became a man leading a team of oxen, and his wife, Fern Jessee, was the model for the main pioneer woman figure in the center of the mural. Jessee’s children contributed arms and legs to some of the Native American figures. Benton’s companion on his trip to Oklahoma and Colorado, Charles Banks Wilson, became a French voyageur on the right, or eastern, side of the mural. Wilson led Benton to a Native American woman living in Kansas City, Angie Perry, who became the large female Cheyenne figure on the mural’s western side, just over the Pawnee warrior’s right shoulder.

On June 5, 1959, Benton wrote to Truman about the progress he had made on the mural project. "The research part is finally all done. My last trip to Denver for certain accessories of the fur trade and to Chimney and Courthouse Rocks for the topography of the Oregon Trail section of the mural rounds up my factual needs." In the fall of 1959, following his usual summer holiday at Martha’s Vineyard, he made a new version of the sculptural model of the mural design and a final cartoon. The Truman Library staff and others, meanwhile, were working to prepare the entrance lobby wall to receive the mural. The wall was sealed, Belgian linen was glued to it, and liquid latex gesso was spread over the linen. "Everybody [here]," Truman wrote to Benton on October 7, 1959, "is working his head off to get ready for you when you come to the point when you want to tackle the wall."

It was time to start painting the mural. On November 16, 1959, Benton’s arrival at the library for his first day’s work on the mural became the occasion for a press conference in the lobby. Photographers took pictures as Truman and Benton held up the mural cartoon. Benton explained all the preparatory work he had done and described the mural theme in detail. Then he climbed up on the scaffolding that had been placed along the mural wall to show how he would do his work. Truman promised, when the time was right, to paint in the mural’s first brush stroke. The next day, two of Benton’s assistants continued the work, already begun, of drawing a grid over the lobby wall and transferring in pencil the mural design from the final cartoon to the wall. About four weeks later, on December 12, Benton climbed up onto the scaffolding and began painting. Sometime during the day, the scaffolding began to shake, and Benton saw that Truman was climbing up to join him. He took the brush from Benton’s hand and, as he had promised, painted in a few strokes of blue in the prairie sky at the mural’s upper right hand corner.

Benton was a daily presence at the Truman Library for about six months. He arrived early every morning. He was a small man, not much over five feet tall, and though he was 70 years old, he could still climb up on the scaffolding every day. He liked a pipe and cigars and probably always smelled of them. He looked rumpled, and his plaid shirts sometimes looked slept in. He carried with him to the library every day a container of his wife’s homemade soup, which he warmed up and ate at noontime in the staff lunch room. He was friendly with library staff as he took his soup and would chat about anything that came up. Everyone liked him.

Day after day, Benton climbed the scaffolding and filled in the penciled design with bright colors. He referred often to the sketches and drawings he had made of his models, artifacts, landscape scenes, and flora, and he kept the clay model nearby to remind him of the simulated third dimension he wanted the mural to have.

By late spring 1960, Benton had substantially completed the main portion of the mural; only the lower portion, called the predella and covering the bottom four feet of wall space, remained to be done. He had to separate this lower part of the mural from the rest, as he explained, because "perspectives at the bottom of the wall space became too acute." After his summer break in Martha’s Vineyard, during which he developed his ideas for the predella, he completed this final part of the mural the following fall and winter.

The predella was for Benton almost a separate work from the upper section of the mural. The latter told in a great sweeping, energetic arc the story of the westward movement of American civilization through the Indian lands west of Independence. The predella, in contrast, was to be a quiet portrait of Independence in the 1840s, with the town courthouse on the right, or eastern, side, and the river landing with a steamboat at the dock on the left, or western, side. In between men, wagons and horses go about the slow work of hauling freight up to the town. Time passes slowly in this scene, or not at all, and it is suffused with a sweet rosy haze.

Benton had developed bursitis, and he had to be helped up from the floor after every session of work on the predella. He couldn’t drive any longer; the Kansas City police took him back and forth each day between his home and the Truman Library.

Benton finished the mural in March 1961. An elaborate dedication ceremony was held at the library on April 15, which was Benton’s 72nd birthday. The program began at 3 p.m. Despite a raw windy day, about 2,000 people gathered in the plaza in front of the library’s front steps to hear the featured speakers. Truman told the crowd that Benton was "the best muralist in the country" and that Independence and the Opening of the West was his best mural. He also said wryly that he got along well with the crusty artist, and "that’s hard for anyone to do." Benton thanked Truman for being maybe the best patron he had ever had—a patron who kept his opinions to himself and let the artist finish his work. He said Truman, "possessed the equipment, as a historian, to be a really disturbing kibitzer if he’d wanted to. . . . Instead, he permitted my work here to develop on its original plan and through its own logic to its own kind of completion." Chief Justice Earl Warren spoke solemnly about the mural’s serious purpose. "As our people come to visit the Truman Library," he said, "their eyes will fall upon this great mural, and if they see it with eyes brightened by a knowledge of our own history every figure in it will have meaning for them and will help to build within their hearts a deep and abiding patriotism. The knowledge of our heroic past will open vistas for them into our future."

The Truman Library’s lobby was no longer an empty space. Instead it was filled with Native American warriors and traders, pioneers, frontiersmen, blacksmiths, wagons, horses and oxen, landmarks of the Oregon and Santa Fe Trails, blue sky, swirling clouds, a courthouse, vivid colors, a feeling of motion, a sense of incident.

Benton wrote a long description of the mural while he was still working on it. The mural is filled, he wrote, with "symbolic figures, symbolic happenings, representing a multiplicity of real individuals and real events." The main drama in the mural’s upper portion is the confrontation of hunter, trapper, frontiersman, and finally pioneer settler with the Native Americans of the Great Plains. A large settler figure is given a central position because, as Benton argues, putting forward his reading of the westward movement, "it was he, and she, who set the seal of accomplished fact on our continental destiny." The predella shows "Independence in the late 1840s and the Missouri River landing where arrived most of the goods and people which changed Independence from a quiet backwoods settlement to a gateway of destiny."

Over 8 million Truman Library visitors have encountered Independence and the Opening of the West since it was completed in the spring of 1961. Some of these people have perhaps only been impressed by the mural’s bright colors and feeling of energetic movement; others have looked and thought more carefully and had a meaningful aesthetic and educational experience. Library docents skillfully explain the meanings in the mural to visitors and especially to groups of school children. An exhibit at the base of the mural describes for visitors how Benton created the mural.

Independence and the Opening of the West probably didn’t appeal to many art critics. One critic condemned its "bland idealization" and called it "an exquisitely painted decoration, a thousand-piece interlocking jigsaw puzzle." An art historian, writing almost 30 years after the mural was completed, called it Benton’s "greatest tour de force in the field of history painting: literally thousands of objects, each carefully researched, are assembled into a flowing, organized composition."

On December 27, 1972, Benton came to the Truman Library to pay his last respects to Harry S. Truman, whose body lay in state in the lobby in front of the mural. A young man who would many years later become a library docent was in the lobby too. He saw Benton as the old artist stood near Truman’s casket, tears running down his face.

Thomas Hart Benton died of a heart attack in his backyard studio at his home in Kansas City just over two years later, on January 19, 1975. It was evening; he had finished dinner, and he had gone into his studio to look over a new mural that he had just completed. It was called The Sources of Country Music, which he had painted for the Country Music Hall of Fame in Nashville, Tennessee. He wasn’t sure he was satisfied with it yet, but he told his wife that if he decided it was all right, he would sign it. He fell over dead before he had a chance. He had said some years earlier that he didn’t care whether he died now or later, as long as he always had plenty of work to do. He always did.

Raymond H. Geselbracht is special assistant to the director of the Harry S. Truman Library in Independence, Missouri. His contributions to Prologue include articles on Truman’s relationship with the Marx Brothers, his love of poker, his school days in Independence, and his first (rejected) proposal of marriage to Bess Wallace.

Note on Sources

Thomas Hart Benton’s "The President and Me: An Intimate Story," Gateway Heritage (Winter 1995–96): 3–17 (contained within "Highballs and High Stakes: The President, the painter, and the Truman Library Mural," beginning on page 2, edited by Tim Fox) describes the genesis of the Truman Library mural. Benton’s An Artist in America (Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 1983, 4th rev. ed.), pp. 347–361, covers the entire mural story. Benton described the mural itself in an essay intended primarily for Truman Library visitors, "Independence and the Opening of the West," which was published by the Truman Library in 1961. All three of these items are in the Truman Library’s vertical file.

Truman’s correspondence with Benton is in Truman’s Post Presidential Papers and in the Records of the Harry S. Truman Library, Inc. Truman’s letter about The Kentuckian (to Abraham Bernstein, Jan. 7, 1955), which he decided not to mail, is in his Post Presidential Papers, as is his letter to David Lloyd (Dec. 1, 1958) in which he says he and Benton have reached understanding regarding the mural design. His letter to his daughter Margaret (Oct. 19, 1955) in which he laments his poor opinion of Benton’s art is in Margaret Truman, ed., Letters from Father: The Truman Family’s Personal Correspondence (New York: Arbor House, 1981).

The Harry S. Truman Library, Inc.’s records include several items that are quoted or otherwise used: the library corporation’s June 6, 1958, press release, Benton’s "Mural Project" memorandum, his address at the April 15, 1961, dedication ceremony, and his letter of February 10, 1958, to David Lloyd.

Earl Warren’s speech at the dedication of the Benton mural is in Truman’s Post Presidential Papers.

Charles Banks Wilson, "On the Trail with Tom Benton," Oklahoma’s Orbit, May 13, 1962 (and in the Truman Library’s vertical file), tells the story of Benton’s search for models in Oklahoma. The following interviews were used: Robert S. Gallagher interview with Benton, American Heritage, June 1973 (Truman not in the mural); Truman Library oral history interview with Benton (Apr. 21, 1964) and with Randall and Fern Jessee (models for some of the mural figures; May 19, 1964), and interviews conducted by the author with Charles Banks Wilson (research trip to Oklahoma and Colorado; Feb. 12, 2001), John C. Curry (Benton at Truman Library; Nov. 5, 2008), Steven Sitton (Benton’s death; Nov. 17, 2008), and Karl Welch (Benton at Truman’s lying in state; Nov. 17, 2008).

Newspaper accounts which were used, all of which are in the Truman Library’s vertical file, include the following: John Canady, "A Look at Benton and Della Bella," The New York Times, Nov. 30, 1968; "Benton, Muralist, does a Clay Model First," The New York Times, July 26, 1959; "Artist Benton on the Job," Independence Examiner, Nov. 17, 1959; "Benton’s Vision of Truman Library Mural Takes Shape," Kansas City Star, Dec. 21, 1958; "Truman’s Restraint as a Critic Earns Plaudits With Benton’s Artistic Genius," Kansas City Star, Apr. 16, 1961; "Truman Library ‘National Cultural Institution’," Independence Examiner, Apr. 18, 1961; and "Dedicate Benton Mural as ‘Best’," St. Joseph News-Press, Apr. 16, 1961.