Coastal Bastions and Frontier Forts

Records of U.S. Military Posts, 1821–1920

Fall 2009, Vol. 41, No. 3 | Genealogy Notes

By John P. Deeben

In the early 1890s, the brief but personal stories of two very different people converged in a small cemetery at a remote outpost on the Montana frontier.

On August 26, 1891, 1st Sgt. John Robinson of the 25th U.S. Infantry and his wife, Mahala, had a son at Fort Custer, a small military garrison only 11 miles from the site of Lt. Col. George Custer's 1876 defeat. Sadly, 10 months later on June 6, 1892, baby John died after a hasty baptism by post chaplain Mahlon C. Blaine. According to the records of the post quartermaster, the infant's gravesite was in row C, lot no. 14, of the post cemetery.1

Two years after John Robinson died, another unexpected death occurred at the fort. On the night of September 12, 1894, Pvt. Thad Robson of Company B, 10th U.S. Cavalry, shot and killed for unknown reasons fellow trooper James Williams. A 21-year-old teamster from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Williams had been a recent recruit, joining the 10th Cavalry on December 7, 1892. Two days later, Williams was buried in the post cemetery. His grave, no. 21, occupied the same row as John Robinson's. Within two years the U.S. Army disinterred both remains, along with numerous others, and sent them for reburial to the recently established national cemetery on the grounds of the Custer Battlefield National Monument (known today as the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument.) The War Department closed Fort Custer soon after on April 17, 1898.2

The methodology to locate basic information about military service has long been established in genealogy research. Compiled military service records provide the essential summary of a volunteer soldier's career, while registers of enlistment from the Adjutant General's Office of the War Department offer succinct descriptions of service for Regular Army enlisted men. Fleshing out the more interesting and personal details of military service, such as the birth and death of a soldier's child or the murder of a young recruit, often requires delving into lesser known records. For Regular Army soldiers in particular, the records of U.S. military posts often document such information, from the daily activities of a particular fort to descriptions of individual soldiers and their duties. As the stories of John Robinson and James Williams attest, military post records frequently contain unexpected but useful genealogy related material.

Historical Background

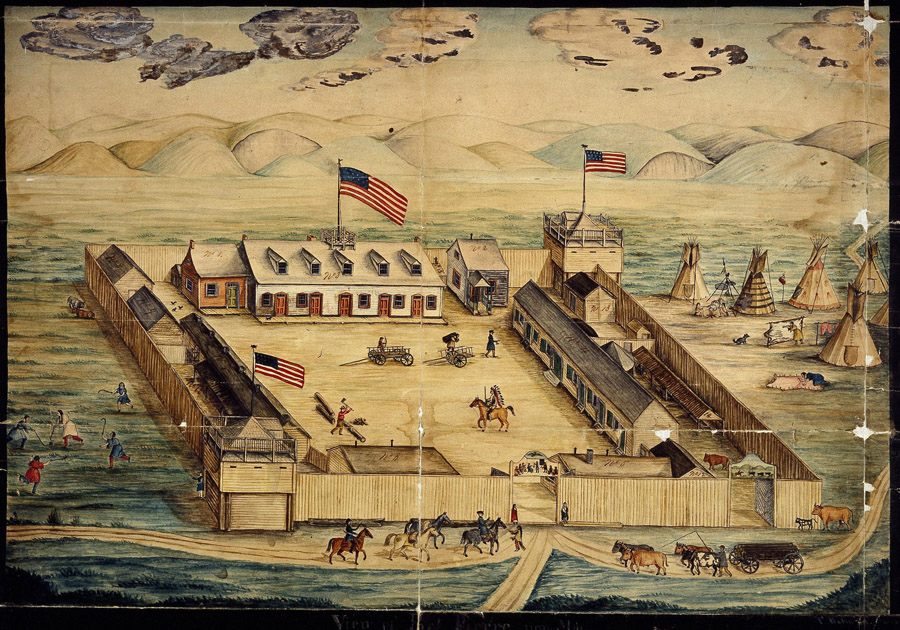

The early federal government continued a longstanding colonial practice of setting aside tracts of public land for military use. These locations often became the sites of fortified garrisons of varying size and design. The protection of frontier settlements from foreign encroachments and Native American attacks had always been a paramount concern; by the early 1790s a half dozen garrisoned posts dotted the western borders of the young republic. The need to defend against foreign threats also led to the construction of seacoast fortresses to safeguard vital coastal channels, tributaries, and inland ports. By the early 19th century, following the end of the First Seminole War in 1818, a network of 73 military posts protected the nation.3

The expansion of the western frontier further fueled the construction of installations. The acquisition of land from Mexico in 1848 spurred the need for a constant military presence from New Mexico to California and the Pacific Northwest. Indian wars necessitated the regular presence of U.S. troops to maintain the peace. During the Civil War, the Union army established new outposts as it reoccupied Southern territory. At war's end, Federal troops on occupation duty reclaimed abandoned forts and erected temporary posts.4

In the latter 19th century, the function of military outposts began to change. At first, continued Indian warfare on the frontier, especially in the northern plains and southwest, caused the U.S. military to construct more forts, most of them to guard Indian nations as they were subdued and relocated to reservations.

The cessation of Indian wars by the early 1890s and the advance of the railroads through the West diminished the need for posts. The military no longer required intricate networks of fortified posts to protect territory, enforce law and order, or keep transportation routes open. As a result, many forts became obsolete and evolved from protective strongholds to training facilities. In the early 20th century, during the United States' participation in World War I, training camps flourished across the country, but the War Department immediately abandoned most of them after the war ended.5

Military garrisons created many records to document their daily activities. In the early 19th century, however, the federal government seldom regulated such records. Not until 1857 did the War Department begin to issue guidelines that identified certain types of records to be created along with specific filing procedures. In 1865 the War Department required the records of abandoned posts to be forwarded to the Adjutant General's Office for preservation. This belated oversight, along with human negligence, the effects of nature, and the relatively primitive environment in which many of these garrisons operated, contributed to the paucity of records for many early forts and noticeable gaps in later records. Despite such inherent problems, military post records still offer useful historical insight.6

Records of the Post Headquarters

The existing records of 19th-century U.S. military posts are part of the Records of United States Army Continental Commands, 1821–1920 (Record Group [RG] 393), at the National Archives. The textual records in this record group contain material relating to all domestic field establishments of the U.S. Army organized into five parts, including 1) geographical divisions, departments, and military (Reconstruction) districts; 2) polyonymous (multiple named) successions of commands, 1861–1870, including armies, army corps, tactical divisions, and brigades; 3) geographical districts and subdistricts; 4) military installations (posts, camps, and stations), 1821–1881, whose records are interfiled or otherwise inseparable from higher level organizations; and 5) military installations, 1821–1920, whose records exist as separate or "stand alone" entities. The records of most 19th-century posts fall within the last category, although it is occasionally possible to locate related material within the other subdivisions of the record group.

Military post records are generally divided into two parts: headquarters records created or maintained by the post commander (or his designate) and records created by subordinate staff officers. Headquarters records documented administrative activities as well as general information about post personnel. As the highest ranking officer in charge, the post commander supervised the overall affairs of the fort, including safety, defense, discipline, and the physical condition of the facilities, especially the living quarters; the preservation and usage of government equipment and supplies; and the enforcement of federal laws and Army regulations. A lower ranking officer usually assisted the commander as the post adjutant or chief record keeper. Following established protocol, the adjutant handled incoming correspondence and disposed of or distributed all papers received; answered letters; signed endorsements; supervised clerks, orderlies, and guards; distributed and filed general orders; drafted and signed special orders; and handled all personnel records.7

Letters sent and received at headquarters typically documented the routine activities of the post and surrounding community. The adjutant transcribed outgoing correspondence in bound volumes including the date and the name of the recipient. The letters sent from Fort Apache, Arizona Territory, show that on June 26, 1872, commanding officer Maj. A. J. Dallas of the 23rd U.S. Infantry notified the Adjutant General of the Department of Arizona that he had discharged Pvt. Martin K. Nelson of Troop M, Fifth U.S. Cavalry, per Special Order 102. Since Nelson had previously served as the post's Indian interpreter, Dallas informed headquarters that he temporarily hired Nelson as a "post guide" to retain his valuable language skills. Noting "when this man leaves I shall be without the means of communicating with the Indians," Dallas requested authorization to pay Nelson $85 per month plus rations for his continued service as a civilian employee.8

For letters received at the post, the adjutant usually maintained an unbound correspondence file but also documented each letter in a bound register. The register entries contained the number assigned to the incoming letter, the name and office of the author, the place and date of the letter and the date it was received, and a brief summary of the contents. A remarks column also indicated the disposition of each dispatch. A typical register entry for Fort Laramie, Wyoming, showed the commanding officer received a communication from the Department of the Platte at Omaha, Nebraska, on December 14, 1876, requesting the farrier of the post to appear at Fort D.A. Russell near Cheyenne for examination "as to his qualification for the position of Veterinary Surgeon." The adjutant distributed three copies of the letter to the farrier, his company commanding officer, and the headquarters correspondence file.9 Other communications, such as telegrams sent and received, were handled in similar fashion. Quite often, incoming telegrams were simply interfiled within the existing correspondence series.

Issuances of the post, including general and special orders, circulars, and memorandums, typically disseminated important instructions or announcements in a more official format. General orders covered subject matter deemed significant to the garrison as a whole, such as War Department orders and regulations, while special orders conveyed instructions or information to specific groups or individuals. In both cases, the orders documented information about military activity at the post.

Concerning information affecting the entire post, Maj. J. K. Mizner of Fort Richardson, Texas, issued General Order 84 on July 11, 1871. Facing the prospects of "an unusually dry season," Mizner ordered the garrison to restrict public usage of the water supply for any unnecessary activity—including bathing, washing clothes, and other "nuisances"—in order to preserve the purity of the existing water holes.10 Regarding specific instructions to individuals, Col. John Gibbon of Fort Shaw, Montana Territory, issued Special Order 169 on November 22, 1870, which detailed troopers William Smith, John Greene, and William J. Tunstan, all of the Seventh U.S. Infantry, to temporary duty with the post quartermaster. Special Order 170, dated November 28, 1870, further authorized the quartermaster to purchase six lanterns and 40 gallons of lard oil "for the purpose of lighting the fort."11

Similar to general orders, circulars and memorandums were issued to the garrison at large, but their content usually dealt with specific internal matters including inspections, drills, parades, payment of troops, arrangements for funerals, and guard mount assignments.12 The post adjutant usually recorded these various issuances in bound volumes while paper notices were posted for public inspection. The adjutant occasionally maintained additional files of original issuances received from higher commands.

Headquarters Records about Personnel

In addition to routine business and administrative activities, headquarters records also documented general information about lower-ranking personnel at the post. Some forts maintained descriptive books about recruits, enlisted men, and noncommissioned officers (although not all of them have survived.) The ledgers included the date and place of enlistment; date of assignment to the post; descriptions of personnel or disciplinary actions; and status of health and pay. Personal information ranged from the soldier’s date and place of birth and marital status to physical descriptions including height, weight, eye and hair color, and general complexion.13 A few forts maintained similar volumes for civilian employees. The military cantonment at North Fork on the Canadian River, Indian Territory (Oklahoma) maintained a register of civilians that identified each employee's name, age, physical description, place of birth (state or kingdom, and town or county), occupation, physical peculiarities, and remarks regarding place or department of employment. Later entries also noted dates of arrival and departure from the post.14

Other descriptive registers documented personnel actions, such as passes issued to soldiers and duty assignments as well as furloughs and discharges granted. The register of enlisted men discharged from Fort Bridger, Wyoming Territory, between January 1869 and March 1878 recorded each soldier's name, rank, company and regiment, reason for discharge, the date of discharge from service, a brief character description, and miscellaneous remarks. Pvt. Charles Stratton, a musician at Fort Bridger whose enlistment expired on August 19, 1874, was favorably characterized as "a respectable and reliable soldier, an alto player and a first-class drummer."15 A more detailed register from Fort Snelling, Minnesota, chronicled not only the military service of every soldier discharged between 1896 and 1909 (including name, rank, unit, place and date of enlistment, term of service, date and nature of disability, and date of discharge), but also personal information such as age, place of birth, occupation, and a physical description.16

Disciplinary actions against personnel generated yet other descriptive records. For individuals brought before summary or garrison courts-martial, some forts maintained registers of the charges and specifications as well as records of the trial proceedings.17 (The War Department later disposed of many of these lower court records, generally preferring to retain only records of general courts-martial.) The charges and specifications listed the specific infractions committed, described the manner or events in which the infractions occurred, and also identified the name and unit of the accused, the date of the charges, names of witnesses, and the date of approval for the indictment and trial. The record of proceedings for summary and garrison courts-martial often included the name, rank, and unit of the accused; a description of the charges and specifications preferred; the names of witnesses; dates of arrest and arraignment; plea of the accused; the finding of the court; and action by the commanding officer.18

Cpl. Joseph Gamache of Company F, 22nd U.S. Infantry, ran afoul of military authorities at Fort Keogh, Montana, on several occasions. On the night of May 27, 1892, he left the fort without permission and wound up in a drunken brawl in nearby Miles City, where local authorities duly arrested him for disorderly conduct. For breaching military rules and etiquette, Gamache also faced arraignment before a summary court-martial on May 30, 1892, charged with being absent without leave and conduct unbecoming an officer. First Sgt. R. F. Rumpff of Company F and Marshal Jackson of Miles City served as witnesses for the prosecution. After pleading guilty to both charges, the court-martial sentenced Gamache to a reduction in rank to private soldier. Less than a week later, Gamache committed another infraction when the officer of the day caught him asleep at his post while on sentry duty in the early morning hours of June 2, 1892. (Detailed court proceedings do not exist for this second offense.)19

Convicted prisoners are documented in various records compiled by the fort headquarters—or the provost marshal, if the post maintained such an officer. Descriptive books in most respects resembled those for other post personnel. The descriptions usually included the prisoner's name, age, physical description, place of birth, civilian occupation, and enlistment information. General registers of prisoners also resembled the summary court records, listing each prisoner's name, unit, the charge and sentence imposed, date confined to prison and term of sentence, and miscellaneous remarks, which usually included the date and reason for release from confinement. Other monthly or biweekly reports of prisoners contained similar types of information. The guard force at each post also generated daily reports that often included a listing of personnel assigned to guard duty as well as the names of all military and civilian prisoners, their dates of confinement, reasons for confinement or charges preferred, and the sentences imposed.20

The descriptive books and general registers provide a composite history of an individual prisoner. Pvt. John Lee, a 23-year-old laborer from Ireland, enlisted in the Eighth U.S. Infantry at Louisville, Kentucky, on June 12, 1867, for three years. Less than a year into his service, Lee physically assaulted a superior officer and was convicted by a general court-martial on January 30, 1868. Lee's sentence, approved by the Third U.S. Military District in Atlanta, included forfeiture of all pay and allowances "except the just dues of the laundress," confinement at hard labor for two years at Fort Pulaski, Georgia, "wearing a ball and chain each alternate month, the chain to be riveted to his ankle and to weigh 24 lbs.," and a dishonorable discharge. A year into his sentence, Lee escaped from Fort Pulaski on May 21, 1869, but was soon recaptured in Atlanta and served out the remainder of his prison term until February 12, 1870.21

Records of Staff Officers

Following a hierarchy authorized by military protocol, the post commander employed a staff of subordinate officers who supervised the lower level administrative offices of the fort, including the Quartermaster Department, the recruiting office, and the post hospital. The records and filing methods created and used by these officers often mirrored those at the headquarters level, documenting their specialized duties in greater detail. In the process, certain staff officers sometimes compiled more explicit records about individuals. It is important to remember, however, that many forts did not always maintain a full complement of staff officers; the related records therefore are not complete for every post.

The records of the post chaplain most typically contained such personal information and vital statistics about individuals. Primarily responsible for the spiritual well being of the fort’s inhabitants, the chaplain performed all essential religious and civil ceremonies, including baptisms of children born at the post, marriages of post personnel, and last rites for the deceased. The chaplain usually recorded these activities in designated registers (although sometimes such ledgers were maintained by the post surgeon if a chaplain was not present).22

When baptisms occurred at a post, the chaplain usually listed the child's name, place and date of birth, and the names of the parents. Marriage entries included the names of the couple, the date and place of the ceremony, and the names of witnesses. Death and funeral records contained the name of the deceased, their age, place of birth, date and cause of death, and the date and place of burial. In addition to christening John Robinson, Chaplain Blaine at Fort Custer also performed two adult baptisms in the Little Big Horn River on April 16, 1892. The baptismal candidates were Cpl. James P. Dundee and Pvt. Thomas Porter, both of Company A, 25th U.S. Infantry. Blaine also conducted 12 weddings and recorded four deaths, including the murder of Yem Lee, a Chinese employee at the post laundry who was killed by unknown assailants on October 12, 1891.23

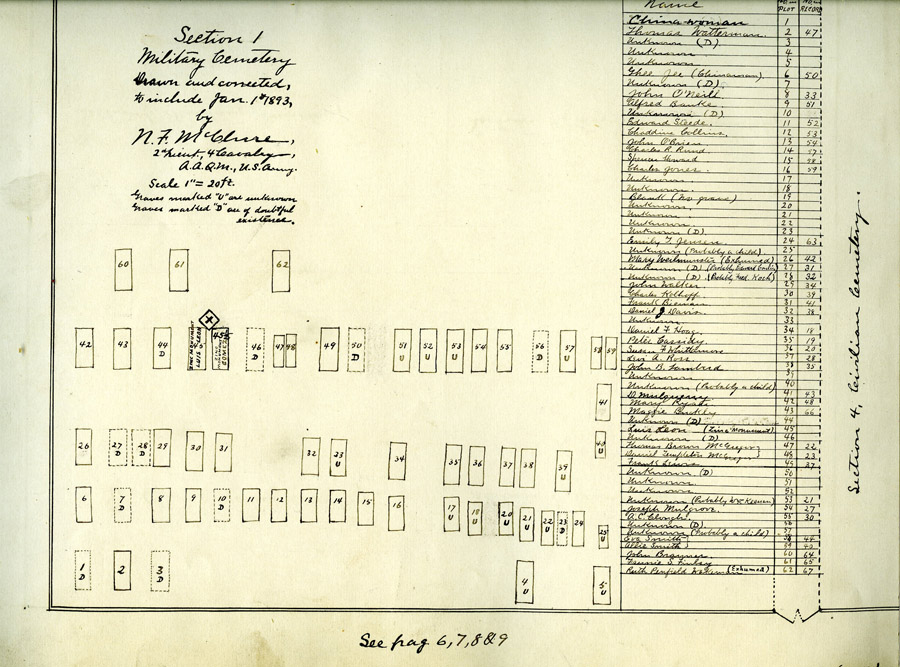

When deaths occurred, the post quartermaster assumed responsibility for the disposition of the remains. In that capacity he supervised the post cemetery and maintained records of military and civilian burials. In the absence of a quartermaster, the post surgeon or commanding officer recorded the burials. Registers of interments identified the name, rank, and unit of the deceased; the grave number; date of death and burial; and remarks relating to the removal of bodies to and from other cemeteries. Sometimes the registers included hand drawn maps or plats of the post cemetery showing the layout of sections, rows, and locations of individual graves. General registers and reports of deaths also listed personal information about the deceased, including residence before enlistment, conjugal condition (whether married or single), place of birth, age, and cause of death. If the deceased left a widow, the reports also noted her current residence.

Death reports compiled by the quartermaster at Fort Duncan, Texas, from 1869 to 1879 included a statement for Pvt. Noah Hardison of Company K, 41st U.S. Infantry, who died at the post hospital of consumption at age 24 on September 13, 1869. A native of Chattanooga, Tennessee, Hardison was single at the time of his death and was buried in the fort cemetery. The report included a notification to the quartermaster, 1st Lt. James Pratt, Jr., from acting assistant surgeon J. C. Lamont, that verified the date and time of Hardison’s death and also set the date of the funeral on September 14, 1869. The report also contained a standard authorization for Pratt to "receive, and immediately inter, the remains of the person described above . . . and also attend to the setting of the head board at the grave, as provided by the Government and ordered by the Secretary of War."24

As the Hardison death record indicates, post surgeons often shared duties with the quartermaster (and often the chaplain) to document the demise of personnel as well as other general health information. In addition to keeping descriptive books of employees in the Hospital Corps, surgeons maintained various records relating to patients. General registers of patients provided the most complete information, including name; unit; race and place of birth; hospital case number; nature of illness or injury; date, source, and cause of admission to the hospital; a description of treatment or disposition of each case; and date of return to duty.25 Pvt. Charles Schmidt, a native of Baden, Germany, in Company F, Fourth U.S. Artillery, entered the hospital at Fort Snelling, Minnesota, on August 16, 1884, for treatment of a contusion of the left knee he received after being kicked by a horse. The injury healed quickly, and Schmidt returned to duty four days later.26

Patient registers reflected a wide range of illnesses, from gastrointestinal ailments such as diarrhea and dysentery to diseases of the heart and lungs. Physical injuries including fractures, lacerations, and concussions proved frequent during the course of routine duty and also resulted from unruly behavior that sometimes accompanied the monotony of garrison life. In most instances, patients fully recovered—listed in the registers as "cure complete"—and returned to duty, although some cases required further treatment outside the fort, and a few patients died of their ailments. Pvt. Richard Pauli, also of the Fourth U.S. Infantry at Fort Snelling, died in the post hospital on November 17, 1884, from cardiac paralysis after being admitted for acute bronchitis. The patient register listed pulmonary edema and sudden pleural effusion as contributing factors to Pauli’s death, and a subsequent autopsy confirmed the existence of lesions in the lungs.27

Registers of surgical operations provided more detailed information about the condition and treatment of specific patients. In addition to the usual personal data, the registers contained a description and date of the wound or injury; the date and type of operation (amputation, excision, or other); the condition of the injury at the time of the procedure; a postoperative assessment of the patient; progress and treatment; results and cause of death, if applicable; and general remarks, which usually included the name of the attending surgeon. Pvt. Herman Lamprecht of the Seventh U.S. Cavalry at Fort Douglas, Utah, became separated from his command near Carrinne, Utah, in early December 1871. Overtaken by a sudden snowstorm, Lamprecht suffered frostbite on both feet and lower legs. Admitted to the post hospital on December 4, he underwent a double amputation on December 19, performed by post surgeon Edward P. Vollum.28

Lamprecht’s medical condition appeared quite severe at the time of his operation. Dr. Vollum’s surgical notes indicated a "demarcation had formed at the lower third of the legs. All below the lines was in a state of mortification." The surgery, however, went reasonably well. During the procedure, Vollum administered "ether and a little alcohol . . . as an anesthetic," and both stumps were "strapped with adhesive plastic but not bandaged and covered with a cloth." After the operation, the surgeon pronounced the condition of the patient as "good" and noted an encouraging outlook for his recovery: "Progress to date favorable[;] stumps rested on a pillow and kept moist with a solution of carbolic acid."29 Although the final disposition of Lamprecht's medical case was not recorded in the surgeon's ledgers, enlistment records show he eventually received a medical discharge from Fort Douglas on May 16, 1872.30

As part of his responsibility to maintain the physical well being of the garrison, the post surgeon also conducted routine examinations of new recruits. These exams offered yet another source of personal information, including the recruit's name, place of birth (town and state or country), occupation, age, marital status, and a physical description including height, weight, and chest measurement. The surgeon noted peculiar marks or distinguishing features—"varicose scars" and "U.S." tattoos appeared most frequently in the exam records for Fort Snelling—and then indicated whether the recruit was accepted or rejected for service. Common reasons for rejection included poor physique, underweight, myopia, and hernias.31 Additional medical records sometimes included registers of prescriptions issued to patients, many of which contained the original scripts pasted into the ledgers, and registers of certificates of disability for discharge. The latter included either summarized transcripts of certificates issued or file copies of the printed forms.

A few forts compiled records of a unique or unusual nature. During the Civil War, federal posts in Chester, South Carolina; Raleigh, North Carolina; and Key West, Florida, filed oaths of allegiance to the Union cause. Although the format varied among the posts, the oaths generally forbade applicants to bear arms against the United States; give "aid, countenance, counsel or encouragement" to anyone engaged in armed hostility with the federal government; accept or exercise public office under any "pretended authority in hostility" to the United States; or provide voluntary support to anyone engaged in open insurrection. The garrison at Key West Barracks also maintained a file of paroles for prisoners from captured prize vessels. Similar to the oaths of allegiance, these "paroles of honor" required the prisoners to pledge not to bear arms against the United States "or in any way aid, abet, or give comfort to its enemies during the Present War."32

Providing an unusual glimpse into the routine finances of the post, the Engineer Department at Fort Jefferson, Florida, maintained monthly returns of taxes assessed on the salaries of civilian employees from 1862 to 1868. The returns usually consist of a listing of the employees, the name of their office or position held under government contract, the amount of monthly taxable income, the tax rate (usually 3 percent), and the amount of tax assessed. In July 1864, for example, George Phillips earned $75.00 as chief overseer for the department. Applying the 3 percent rate, the fort paymaster deducted $2.25 from his salary.33

Some records also related to inhabitants of the surrounding community. The military post at Jefferson, Texas, kept a register of local county officials during the first years of Reconstruction from 1866 to 1870. Likely maintained as a way to monitor the political rehabilitation of the former Confederate population, the register noted the names, office, dates of election or appointment, and expiration of term of service for various public officials from Marion, Davis, Titus, Harrison, Upshur, Red River, Bowie, Nacogdoches, and Sabine counties. The listings covered everything from administrative offices, including county and district clerk, notary public, surveyor, and commissioner to legal positions such as county judge and attorney, sheriff, and justice of the peace. A remarks column often noted who each candidate preceded in office and whether an official left office early (either by removal, disqualification, or other voluntary reasons.)34

Related Military Records

While Record Group 393 holds the records of 19th-century military forts, information about 18th- and 20th-century installations also exists. A few pre-1821 post records are located in the Records of United States Army Commands (Record Group 98), 1784–1821. These include an orderly book (1786–1787) and garrison returns (1803–1805) for Castle Island (Fort Independence), Boston; an order book (1795–1811) for Fort Johnston, North Carolina; and order books and military provision returns (1806–1816) for the military garrison at New Orleans, Louisiana. The majority of 20th-century post records are arranged in Record Group 394, Records of United States Army Continental Commands, 1920–1942. Consisting of various headquarters records, including correspondence, issuances, morning reports, post diaries, and activity reports, these records cover forts from Camp Anchorage and Chilkoot Barracks, Alaska, to Camp Dix, New Jersey, and other installations along the eastern seaboard and Gulf Coast. The records document the interwar period between the two world wars.35

Over the years the War Department also compiled general historical information about military forts. National Archives Microfilm Publication M661, Historical Information Relating to Military Posts and Other Installations, 1700–1900, contains reports compiled by the Military Reservation Division of the Adjutant General's Office as part of its responsibility to supervise tracts of public land set aside for military purposes. Exhaustively thorough in nature, the reports not only cover permanent and temporary U.S. Army posts but also Confederate garrisons, fortified Indian towns, harbor pilot stations, national cemeteries, civilian blockhouses, and colonial British, French, Dutch, and Spanish fortifications. Entries often identify when and by whom a fort was established and abandoned; a description of the geographic location, including the history, geology, and plant life of the surrounding area; origin or derivation of the post name; names of garrisoned units and their period of assignment; aspects of the descent of its legal title; and construction details.36

Microfilm Publication T912, Brief Histories of U.S. Army Commands (Army Posts) and Descriptions of Their Records, provides information about forts and other installations in a more traditional finding aid format. The publication includes one page scope and content notes, or typed summaries, about the records of each fort in Record Group 393. The summaries contain brief historical outlines of each post and describe the nature and arrangement of available records, including the date range, linear volume of archival material, types of records, and specific date spans. More detailed series descriptions for individual posts are also available in Robert Gruber et al., Preliminary Inventory of the Records of United States Army Continental Commands, 1821–1920, Volume V: Military Installations, 1821–1920, Preliminary Inventory 172 (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration, 1999).

From 1868 to 1913 the Army's surgeon general required post surgeons to compile monthly medical histories of their garrisons. These records included a description of the history and locality of each post, including physical characteristics of the geology, flora, and fauna, and monthly sanitation reports used to evaluate the health of the troops. The historical narratives have been reproduced in M903, Descriptive Commentaries from the Medical Histories of Posts, arranged alphabetically by post. A list of cross references identifies forts that may appear under variant spellings or names. Some of the original ledgers, available in the textual series "Medical Histories of Posts, 1868–1913" (Entry 547) in Record Group 94, Records of the Adjutant General's Office, 1780's–1917, also contain records of births, marriages, and deaths, in addition to general health information. Some of the later volumes include reports of sick and wounded troops in addition to the sanitary reports.37

Specific military post records are also available on microfilm. Monthly returns or personnel reports of posts, camps, and stations are in Microfilm Publication M617, Returns from U.S. Military Posts, 1800–1916. These records comprise the official copies of returns submitted directly to the War Department now located in Record Group 94; in most cases, they are duplicates of the headquarters copies retained by the individual posts (although some of the returns are reproduced from post records in RG 393). The returns generally show the military units stationed at a particular fort; the names and duties of officers; the statistical strength of each unit, including men present, absent, and sick; official communications received; and a record of events. The names of enlisted men are also available in the related series "Muster Rolls of Regular Army Organizations, 1784–October 31, 1912" (Entry 53, RG 94).38

Related inspection reports of early to mid 19th-century military posts, as well as geographical commands and military organizations, are also available in M624, Inspection Reports of the Office of the Inspector General, 1814–1842. Under the provisions of an act of March 3, 1813, establishing the Office of the Inspector General in the War Department, a staff of inspectors held responsibility to examine, investigate, and report on the efficiency, discipline, and welfare of the Army. In that capacity they evaluated the physical condition and general administration of military forts as well as individual troops, arms and equipment, quarters, and officers. Although he narrative reports reflected little organizational standardization, they usually contained extensive detail on a wide range of subject matter. These reports are arranged chronologically with an accompanying index of forts and departments.39

Shortly after the Civil War, the Cemetery Branch in the Office of the Quartermaster General compiled an exhaustive listing of burials at military forts, with most of the information gleaned directly from existing post records or cemetery grave markers. This compilation resulted from the Cemetery Branch's responsibility to establish, maintain, and improve national cemeteries, an effort further influenced by the need to transfer remains from abandoned posts to more permanent locations. These burial listings, part of Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, are available in Microfilm Publication M2014, Burial Registers for Military Posts, Camps, and Stations, 1768–1921. Arranged alphabetically by military post, then chronologically by date of burial, the listings usually identify the name of the deceased, rank, company and regiment, date of death, location of the grave, type of marker (headboard, cross, broken stone, or marble slab), and remarks including cause of death.40

From the beginning of the federal government in 1789, military forts and garrisons composed an essential component of the U.S. military establishment. Situated at the forefront of the nation's internal defenses, they carried out the routine business of the U.S. Army, enforced the policies of the War Department, and generally provided protection and stability to a young and growing nation. Some aspects of that administrative work, however, involved activities of a more personal nature, such as the marriage of personnel, the birth and baptism of children, or the illness and death of soldiers and civilians. Offering a unique view of specific communities in microcosm, the records of U.S. military posts provide useful, detailed insight into the lives of the people who inhabited Army outposts from the densely populated eastern seaboard to the more remote, isolated reaches of the western frontier.

John P. Deeben is a genealogy archives specialist in the Research Support Branch at the National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. He earned B.A. and M.A. degrees in history from Gettysburg College and Pennsylvania State University, respectively.

Records of Individual Military Posts on Microfilm

M989, Headquarters Records of Fort Dodge, Kansas, 1866–1882

M1076, Headquarters Records of Fort Verde, Arizona, 1866–1891

M1077, Headquarters Records of Fort Scott, Kansas, 1869–1873

M1081, Headquarters Records of Fort Cummings, New Mexico, 1863–1873, 1880–1884

M1189, Headquarters Records of Fort Stockton, Texas, 1867–1886

M1466, Headquarters Records of Fort Gibson, Indian Territory, 1830–1857

M1512, Headquarters Records of Fort Sumner, New Mexico, 1862–1869

T320, Letters Sent by the Post Commander at Fort Bayard, New Mexico, 1888–1897

T713, Records of Fort Hays, Kansas (U.S. Army Post), 1866–1889

T837, Selected Records of Kansas Army Posts

T838, Letters Sent, Fort Mojave, Arizona Territory, 1859–1890

Notes

1 Baptismal and death entry for John Robinson, June 6, 1892; Register of Births, Baptisms, Marriages, Deaths, and Interments, 1880–1897 [Entry 111–21]; and burial entry for John Robinson, June 7, 1892; Register of Burials in the Post Cemetery, 1877–1896 [Entry 111–28]; both series in Records of Fort Custer, MT; Records of Military Installations, 1821–1920 (Military Installations); Records of United States Army Continental Commands, 1821–1920, Record Group (RG) 393; National Archives Building, Washington, DC (NAB).

2 Death and burial entries for Pvt. James Williams, Sept. 14, 1894, ibid. For background information about Fort Custer, see Robert Gruber et al., Preliminary Inventory of the Records of United States Army Continental Commands, 1821–1920, Volume V: Military Installations, 1821–1920, PI 172 (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration, 1999), p. 157.

3Gruber et al., PI 172, p. 21.

4Ibid.

5Ibid.

6Ibid., p. 22; Robert B. Matchette et al., Guide to Federal Records in the National Archives of the United States (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration, 1995), online version accessed at http://www.archives.gov/research/guide-fed-records on February 6, 2009.

7Gruber et al., PI 172, p. 8.

8Maj. A. J. Dallas to the Adjutant General, Dept. of Arizona, June 26, 1872; Letters and Telegrams Sent, May 1870–August 1906 [Entry 14–2]; Records of Fort Apache, Arizona Territory; Military Installations; RG 393; NAB.

9Register entry 147, Department of the Platte to C.O. Fort Laramie, Dec. 6, 1876; Registers of Letters and Telegrams Received, November 1876–March 1891 [242–6]; Records of Fort Laramie, WY; RG 393; NAB.

10General Order 84, July 11, 1871; General Orders and Circulars, October 1868–May 1878 [385–10]; Records of Fort Richardson, TX; Military Installations; RG 393; NAB.

11Special Order 169, Nov. 22, 1870, and Special Order 170, Nov. 28, 1870; Special Orders, December 1869–March 1881 [Entry 421–11]; Records of Fort Shaw, Montana; RG 393; NAB.

12Gruber et al., PI 172, p. 25.

13Ibid., p. 27.

14Descriptive Book of Civilian Employees, n.d. [Entry 331–10]; Records of the Cantonment on North Fork, Canadian River, OK; Military Installations; RG 393; NAB.

15 Entry for Pvt. Charles Stratton, Aug. 19, 1874; Register of Soldiers Discharged at the Post, January 1869–March 1878 [Entry 50–20]; Records of Fort Bridger, WY; RG 393; NAB.

16Certificates for Disability Discharge, January 1896–January 1909 [Entry 438–48]; Records of Fort Snelling, MN; RG 393; NAB.

17Summary courts-martial comprised a single officer appointed to try enlisted men up to the rank of staff sergeant for noncapital crimes. Garrison courts-martial included three commissioned officers and a judge advocate. They also could only try noncapital crimes involving noncommissioned officers or enlisted men. Both types of courts-martial had limited authority to inflict punishment, which usually included up to one month of confinement or hard labor or forfeiture of one month's pay. Capital crimes and crimes involving commissioned officers were usually tried outside the fort in general courts-martial at the departmental level. See Gruber et al., PI 172, p. 27.

18Ibid.

19Entry for Joseph Gamache, May 30, 1892; Registers of Summary Courts-Martial, November 1890–February 1903 [Entry 230–32; Entry for Joseph Gamache, June 3, 1892; Charges and Specifications for Summary Courts-Martial, January 1877–May 1896 [Entry 230–34]; both series in Records of Fort Keogh, MT; Military Installations; RG 393; NAB.

20Gruber et al., PI 172, p. 26.

21Entry for Pvt. John Lee, Co. A, Eighth U.S. Infantry; Descriptive Books of General Prisoners, 1868–1873 [Entry 366–5], and Register of General Prisoners, January 1872–October 1873 [Entry 366–6]; both series in Records of Fort Pulaski, GA; Military Installations; RG 393; NAB.

22Registers of births, baptisms, marriages, and deaths for Fort Buford, ND, were maintained by the post surgeon, while those for Fort Wallace, KS, were filed with other miscellaneous headquarters records. See Gruber et al., PI 172, pp. 106, 631.

23Register of Births, Baptisms, Marriages, Deaths, and Interments, 1880–1897 [Entry 111–21]; Records of Fort Custer, MT; Military Installations; RG 393; NAB.

24Record of Death and Interment for Pvt. Noah Hardison, Sept. 13, 1869; Reports of Deaths and Interments, September 1869–September 1879 [Entry 135–26]; Records of Fort Duncan, TT; RG 393; NAB.

25Gruber et al., PI 172, p. 28.

26Entry for Pvt. Charles Schmidt, Aug. 16, 1884; Registers of Patients, January 1884–October 1896 [Entry 438–45]; Records of Fort Snelling, MN; Military Installations; RG 393; NAB.

27Entry for Pvt. Richard Pauli, Nov. 14, 1884; ibid.

28Entry for Herman Lamprecht, Dec. 4, 1871; Registers of Surgical Operations, July 1868–Jan. 1912 [Entry 132–31]; Records of Fort Douglas, UT; RG 393; NAB.

29Ibid.

30Entry for Herman Lamprecht, Oct. 18, 1867; Registers of Enlistments, 1798–1914 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M233, roll 33); Records Relating to the Regular Army, 1798–1926; Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1780's–1917, RG 94; NAB.

31Registers of Medical Examinations for Recruits, November 1879–March 1910 [Entry 438–45]; Records of Fort Snelling, MN; Military Installations; RG 393; NAB.

32Oaths of Allegiance, September–October 1865 [Entry 74–11]; Records of the Post of Chester, SC; and Paroles of Honor, September 1861–August 1863 [Entry 231–15]; Records of Key West Barracks, FL; RG 393; NAB.

33Entries for George Phillips and John Kennedy, July 1864; Tax Returns of Civilian Employees, September 1862–May 1868 [Entry 221–48]; Records of Fort Jefferson, Florida; in ibid.

34Register of County Officials, 1866–1870 [Entry 222–14]; Records of the Post of Jefferson, Texas; ibid.

35Machette et al., Guide to Federal Records in the National Archives of the United States, sections 98.2.5, 394.4.

36David A. Gibson, Historical Information Relating to Military Posts and Other Installations, 1700–1900, Descriptive Pamphlet for National Archives Microfilm Publication M661 (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Service, 1972), pp. 2–3.

37Maida Loescher, Descriptive Commentaries from the Medical Histories of Posts, Descriptive Pamphlet for National Archives Microfilm Publication M903 (Washington, DC: General Services Administration, 1973), pp. 1–2; Lucille H. Pendell and Elizabeth Bethel, Preliminary Inventory of the Records of the Adjutant General's Office, PI 17 (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Service, 1949), p. 109.

38Pendell and Bethel, PI 17, pp. 19, 21–23.

39National Archives and Records Service, Inspection Reports of the Office of the Inspector General, 1814–1842, Descriptive Pamphlet for National Archives Microfilm Publication M624 (Washington, DC: General Services Administration, 1965), pp. 2–3.

40Claire Prechtel–Kluskens, Burial Registers for Military Posts, Camps, and Stations, 1768–1921, Descriptive Pamphlet for National Archives Microfilm Publication M2014 (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration, 1996), pp. 2–3.