Dear Harry. . .Love, Bess

Harry Truman’s Grandson Offers a Preview of Yet-To-Be-Released Letters to His Grandfather

Fall 2009, Vol. 41, No. 3

By Clifton Truman Daniel

© 2009 by Clifton Truman Daniel

My grandparents, Harry and Bess Truman, had one of the great marriages in American politics, a rock-solid partnership based on shared values, mutual respect, and love. It was the foundation for one of the most successful, highly regarded presidencies in United States history.

Of course, you’d never know that from my grandmother.

Grandpa was an open book. He’d tell you exactly what was on his mind. Often, he wrote it down. In addition to his public papers, he preserved scads of receipts, notes, diaries, and other private papers, including 1,316 letters that he wrote to my grandmother between 1910 and 1959. He firmly believed that the American public had the right to know and learn from the mind of their President.

My grandmother, on the other hand, had not been the American public’s President. She thought that her business was her own damn business and nobody else’s.

She was naturally shy and hated having her picture taken. In most of the photos from the 1944 Democratic convention that put Grandpa on the ticket with President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Grandpa and my mother, Margaret, are grinning from ear to ear, waving and shaking hands with everyone in sight. My grandmother is just sitting there, the expression on her face suggesting that she has smelled something horrendous.

Despite being born at the top of Independence, Missouri, society, she was modest and self-effacing. And her view on the role of political wife ran contrary to that of her predecessor, the gregarious and outspoken Eleanor Roosevelt.

“A woman’s place in public,” my grandmother said, “is to sit beside her husband, be silent, and be sure her hat is on straight.”

As First Lady, she discontinued the regular press conferences instituted by Mrs. Roosevelt and issued only a succinct biography. Her favorite interview method thereafter was through written questions. Her usual answer, in print or in person, was “no comment.”

A good deal of this reticence was due to tragedy. Her father, David Willock Wallace, had committed suicide in 1903, when my grandmother was 18. She adored him, and his death was sudden, unexpected, heartbreaking, and in that day and age, shameful. She never spoke of him. What thoughts and feelings she had were reserved for family and close friends, and she was determined to keep it that way.

During their courtship and most of their marriage, my grandparents must have exchanged more than 2,600 letters. That’s a guess since the Truman Library has only about half the correspondence, Grandpa’s half. Most of her half is gone.

One evening close to Christmas in 1955, Grandpa came home from his office in Kansas City and found my grandmother sitting in the living room, burning stacks of those letters in the hearth.

“Bess!” he said in alarm. “What are you doing? Think of history!”

“Oh, I have,” she said and tossed in another stack.

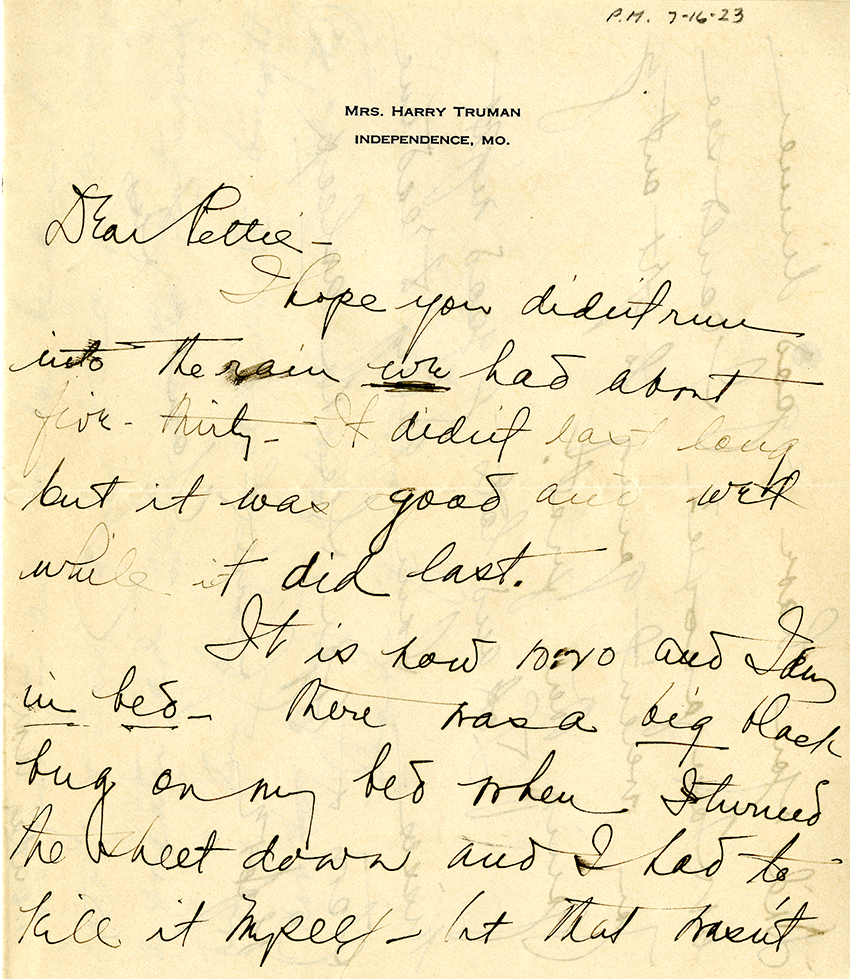

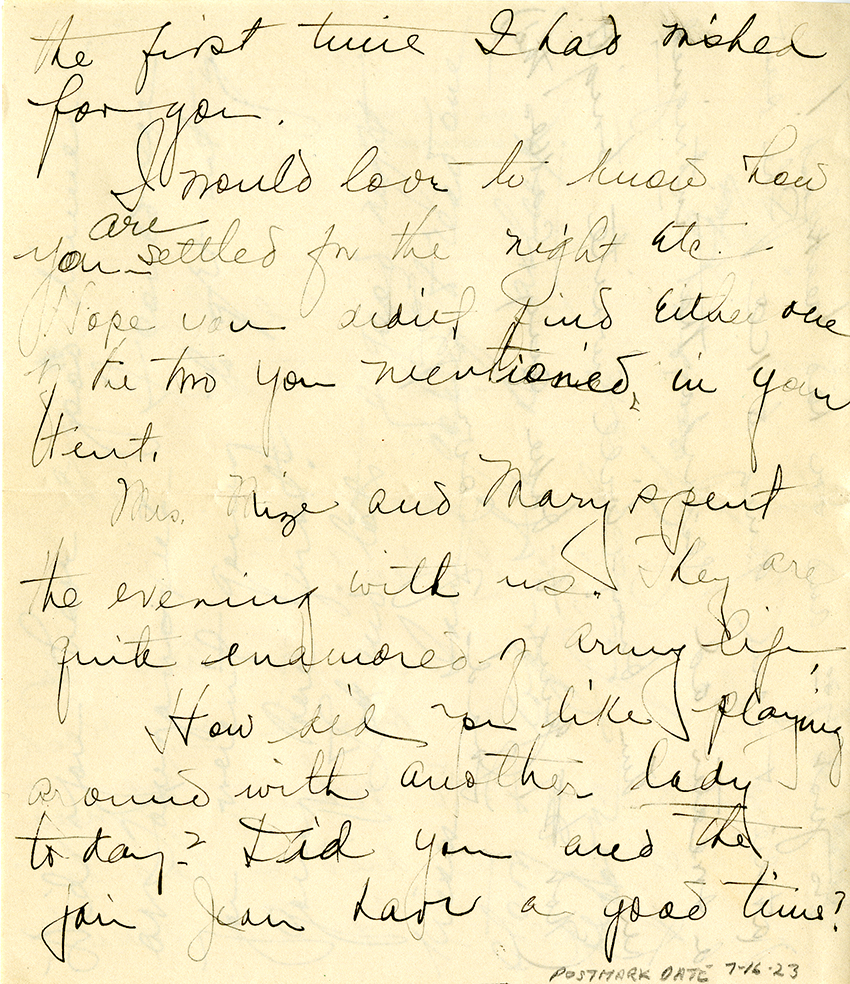

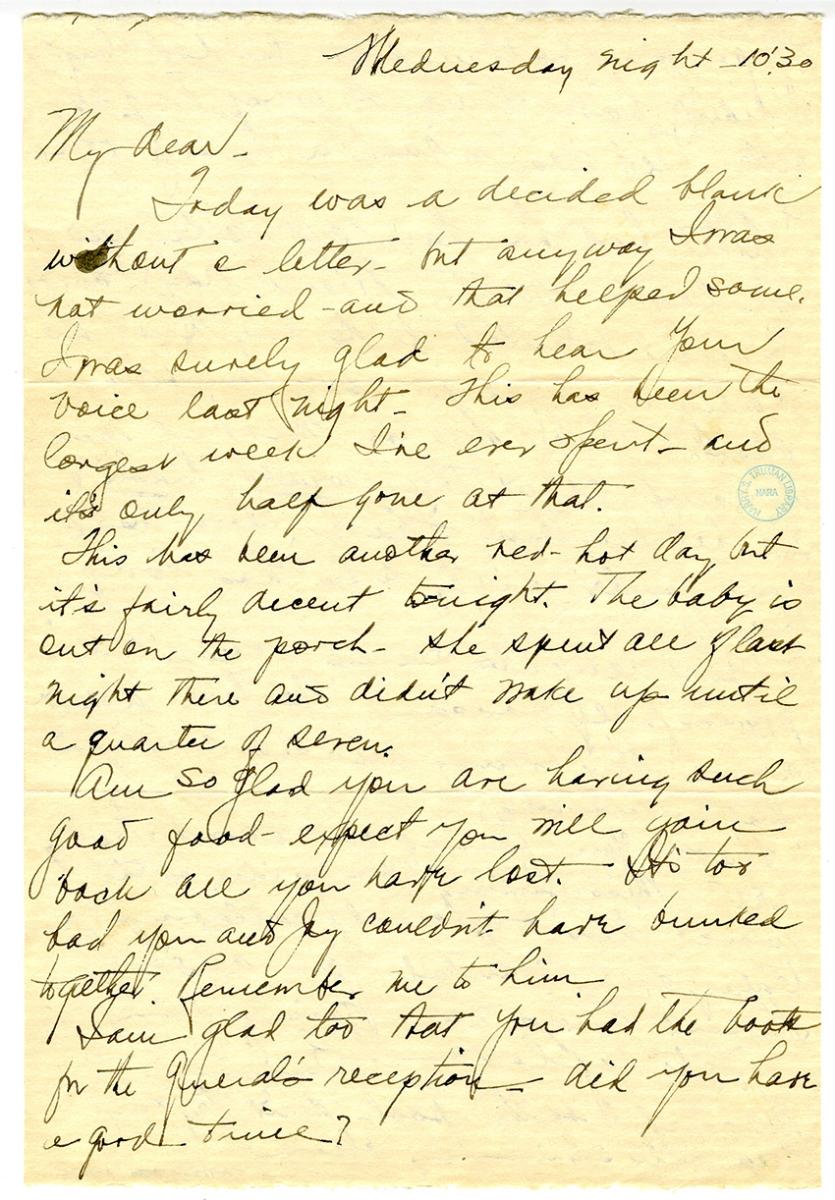

Fortunately, she did not pitch them all into the fire. Thanks to what Ray Geselbracht, special assistant to the director of the Truman Library, called an act of “poor housekeeping,” we know that at 10:20 p.m. on the evening of July 16, 1923, my 38-year-old grandmother was in bed, lonely and unprotected, waging war on the local insect population, species undetermined.

“There was a big black bug on my bed when I turned the sheet down and I had to kill it myself,” she wrote indignantly. “But that wasn’t the first time I had wished for you.”

That morning, my grandfather had taken off for Missouri National Guard training camp at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, something he did every July. He would stay for two weeks. Despite this abandonment—and the bug attack—in the same letter she addressed him affectionately as “Pettie” and inquired about his trip.

“I hope you didn’t run into the rain we had about five-thirty—It didn’t last long but it was good and wet while it did last . . . I would love to know how you are settled for the night etc. . . . Did you have a good dinner at Tonganoxie? I could see you weren’t going to get out of going there first.”

Indeed, Grandpa did not get out of dinner at Tonganoxie, Kansas. The friend driving him, Bill Kirby, wouldn’t drop him off until he’d delivered a second passenger, Jean Settle, to her destination in nearby Lawrence. Not that Grandpa minded. The dinner was worth it.

“We had cold roast country ham, cold roast veal, old fashioned country fried potatoes, three kinds of salad, pickled beets, oranges, four kinds of preserves and jam with ice tea and angle [his spelling] food orange cake with preserves or peaches for desert [his spelling again],” he wrote the next day. “It was a good dinner and worth twice the money.”

Apparently the food kept coming. For breakfast at camp the next morning, he reported, “we had a half grape fruit, cream of wheat, ham, two eggs, two hot cakes and coffee, and I ate it all.”

“That was some breakfast!” my grandmother wrote back. “You’ll have to be pretty strenuous to keep that front down.”

This and the 179 other letters my grandmother overlooked were not tied in neat bundles and squirreled away in a trunk or box. Most had been pushed to the backs of desk drawers or tucked into the pages of books as bookmarks. Truman Library archivists found them in the early 1980s while carrying out an inventory of the home’s contents. Liz Safly, the library’s recently retired research room supervisor, took them to the library in the trunk of her car.

“Just think what would have happened if I’d had an accident,” she said.

My mother, who owned the letters and who died last year, used some of them in her 1985 biography of my grandmother, and 15 were put on display at the library in 1998. But she chose not to release the rest of them, probably respecting grandmother’s wishes. The letters will remain closed to the public for another four years.

The letters span 20 years from 1923, when my grandparents were newly married and my grandfather was beginning his political career as eastern judge of Jackson County, Missouri (county judges are actually county administrators in Missouri) to 1943, when he was a U.S. senator a year away from being nominated for Vice President. There is also a single letter from March 16, 1919, written to Grandpa while he was still overseas following the end of World War I.

The previous month, Grandpa had written:

“Please get ready to march down the aisle with me just as soon as you decently can when I get back,” Grandpa wrote to her from Rosières, France, on February 18, 1919. “I haven’t any place to go but home and I’m busted financially but I love you as madly as a man can and I’ll find all the other things. We’ll be married anywhere you say at any time you mention and if you want only one person or the whole town I don’t care as long as you make it quickly after my arrival. I have some army friends I’d like to ask and my own family and that’s all I care about, and the army friends can go hang if you don’t want ’em. I have enough money to buy a Ford and we can set sail in that and arrive in Happyland at once and quickly.”

“You may invite the entire 35th Division to our wedding if you want to,” she wrote back on March 16, having finally received his letter through the tortured military mail system. “I guess it’s going to be yours as well as mine. I guess we might as well have the church full while we are at it. . . . Hold on to the money for the car! We’ll surely need one. Most anything that will run on four wheels. I’ve been looking at used car bargains today. I’ll frankly confess I’m scared to death of Fords.”

Many of the other letters were written during my grandfather’s annual National Guard encampments, which my grandmother viewed as rests. Even with the drills, exercises, and cold showers they were a welcome break from his regular, stressful routine as judge.

“Well, it’s awfully darned lonesome but I know you are going to get lots of good out of the trip and I’m glad too that you are taking it by yourself for I am sure you needed to get away from everything and everybody,” she wrote on July 17, 1923.

She worried about his health, which may come as a surprise to people used to the image of my grandfather striding around Washington, leaving exhausted reporters and Secret Service agents in his wake. But really, he often pushed himself to the point of exhaustion. When asked once what he did to relax, he said, “work.”

At the start of the July 1923 encampment, when he reported that he’d stood a perfect physical exam, she wrote back that she was glad to hear it but wanted to know just what the camp doctor said about his tonsils.

“Bet he didn’t even look at them,” she grumbled.

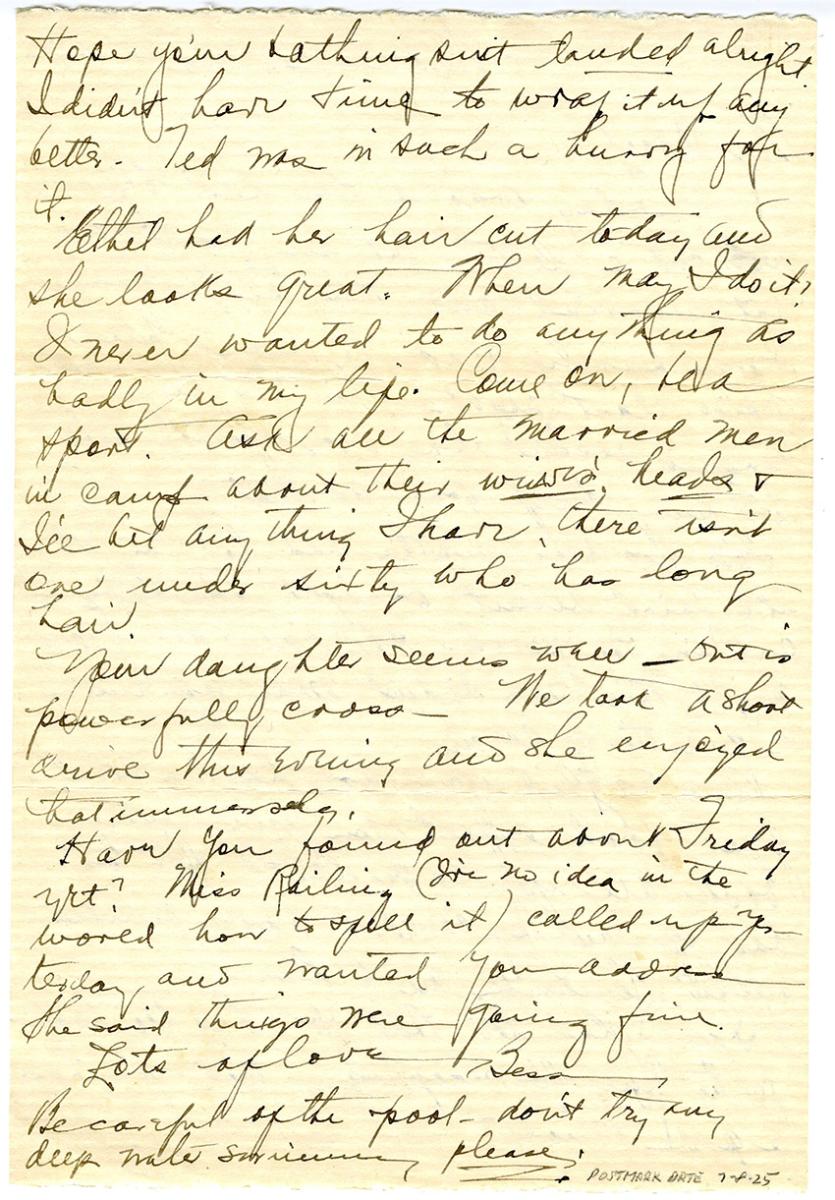

During the July 1925 encampment, she discovered to her dismay that Grandpa and his fellow Guardsmen, training that summer not at Fort Leavenworth but at Fort Riley, Kansas, now had the use of a pool. Needless to say it was unheated.

“I think I told you I went swimming yesterday and it was the coldest pool I was ever in,” Grandpa wrote. “Minnesota lakes have nothing on it. Our showers are the same way. I can’t understand what causes it.”

Her reply contained a tersely worded postscript written in the form of a command: “Be careful of the pool—don’t try any deep water swimming, please!”

Twice he tried to reassure her, first by playing up the rest, relaxation, and health benefits.

“We have swimming parties every afternoon and while the pool is cold as the mischief it’s very good for us,” he wrote cheerily. “I’m as healthy as a farmhand.”

Several days later, he addressed her fears directly.

“The swimming pool isn’t deep or large and it’s always full of the finest swimmers. So don’t worry.”

She was having none of it and closed the discourse handily and succinctly: “Look out for that icy pool that you don’t get one of your attacks of cramps.”

Her fears may have been grounded in personal experience. Neither she nor my mother could swim, at least not well. My grandfather and my father, on the other hand, were fish. The only thing I’d ever seen ruin a nice swim for Grandpa was a couple of grandchildren cannon-balling him.

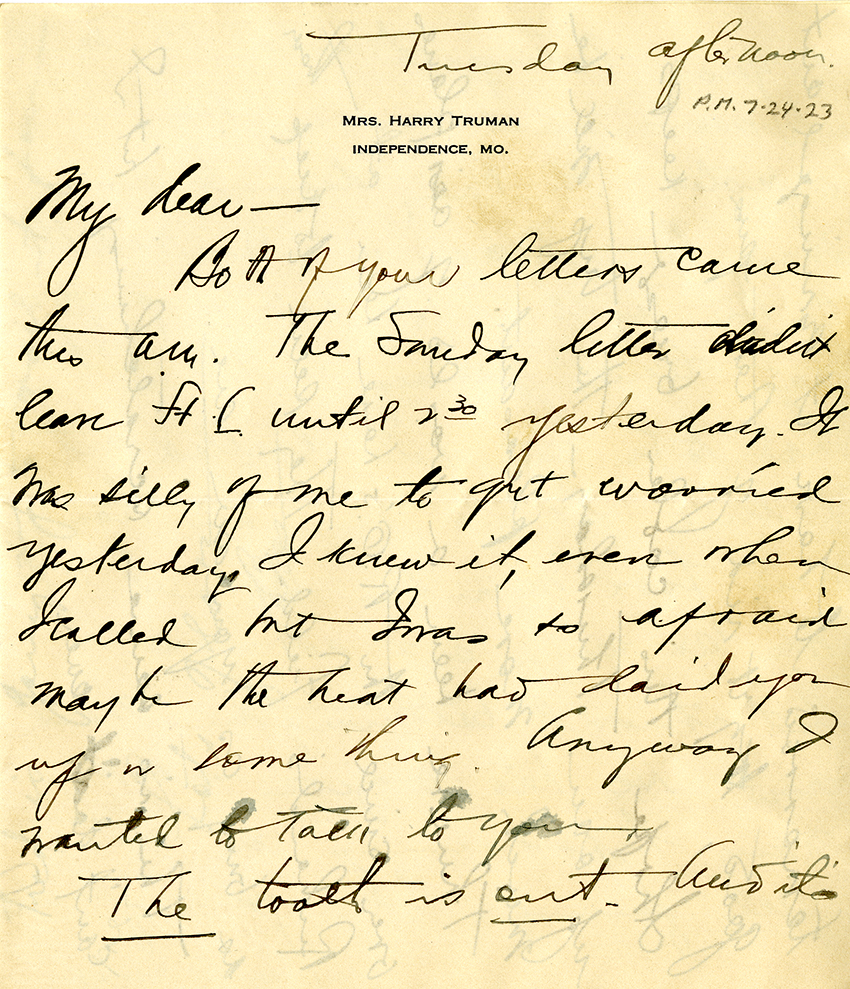

In the summer of 1923, my grandmother had her own health woes, specifically a trio of infected teeth, which she reported to Grandpa in great detail

“Called Dr. Berry this morning—(the pictures came yesterday.) He said there were two he believed should come out—one back one and one front—(just on the side),” she reported on July 17. “He couldn’t tell just how bad they were but that they might be secreting poison. I’m going up tomorrow and maybe have the big one and the (inside) one out. There’s no use putting it off.”

In fact it was put off, which greatly irritated my grandmother since she must have been in considerable pain.

“Dr. Berry wouldn’t pull those teeth ’til Dr. K. had seen the pictures—a mere matter of courtesy!” she wrote indignantly the next day. “I was sort of peeved for I had made up my mind to have two of those out today. He says now he’ll pull them the last of the week. Some day when it rains, I reckon, and he can’t play golf.”

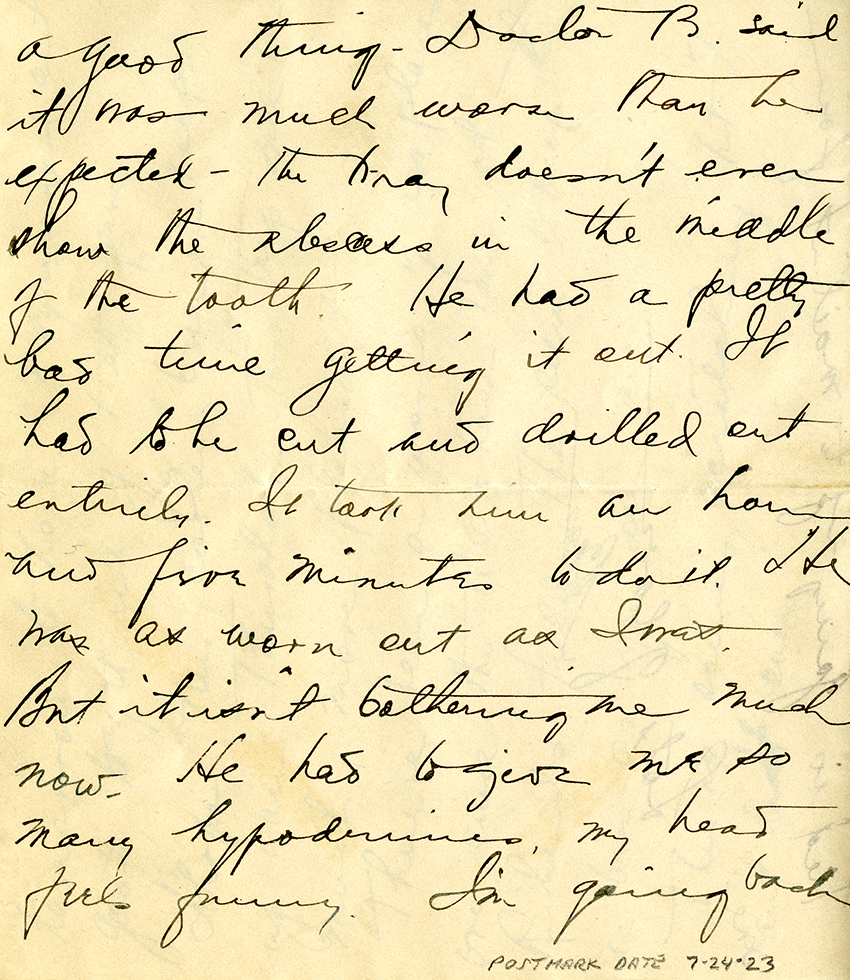

On July 24, Dr. Berry finally pulled the worst of the three teeth, which turned out to be much worse than expected. His x-rays hadn’t revealed a huge abscess at the center of it.

“He had a pretty bad time getting it out,” my grandmother reported. “It had to be cut and drilled out entirely. It took him an hour and five minutes to do it. He was as worn out as I was. But it isn’t bothering me much now. He had to give me so many hypodermics, my head feels funny.”

Grandpa, needless to say, was horrified.

“It sounded mighty fine to hear your voice over the phone but I surely feel like busting a dentist I know of,” he fumed in reply. “It does seem to me that he could have extracted that tooth in a shorter time than that.”

My grandmother soothed him over the course of the next couple of days, reporting that the operation, while long, had been a complete success. She made good use of hyperbole and humor.

“Had a good night and am feeling very much better,” she wrote on July 25. “Am going up to let Dr. Berry wash out the cavity so as to be sure there is no infection. ‘Cavity’ is right, too. It looks like a shell-hole.”

On July 26, she added: “My face feels pretty comfortable. Dr. B. said it looked fine yesterday. He’s right proud of the job he did—but I’m afraid it wore him out so he couldn’t play golf Tuesday afternoon.”

In the summer of 1925, she twisted her ankle. She doesn’t say how, but I like to think that my mother, who was then about 18 months old and spring-loaded, had something to do with it.

“That Doc came to strap up my ankle yesterday—it hurt so badly all day,” my grandmother wrote to Grandpa at Fort Riley on July 6. “He said it is a sprain only. That’s enough, I’ll say.”

The wrapping did the trick, lessening my grandmother’s pain and making her wish she’d asked the doctor to wrap the ankle much sooner. The adhesive stayed on more than a week, and when it came time to remove it, my grandmother did the job herself.

“I took the plaster off my ankle today—with much tribulation,” she reported on July 15. “Used most of the benzene in the county doing it. I hope I never have to have any more dealings with adhesive tape.”

When she wasn’t doctoring herself, or worrying about Grandpa’s health, my grandmother focused on my mother, referred to in the 1925 letters variously as “the kiddie,” “Skinny,” “Miss M.,” and “the baby.”

Mom was born at 219 North Delaware Street on February 17, 1924. At the time she was writing the July 1923 letters, my grandmother was almost two months pregnant, but neither she nor Grandpa mentions it out of superstition. My grandmother had already suffered two miscarriages.

(After the heartbreak of twice coming home to a house filled with baby clothing and furniture, my grandmother pitched all of it. She had nothing for my mother to wear and no place for her to sleep so Mom spent her first night wrapped in a blanket and tucked into a dresser drawer. This was common to folks of their era and, in our case, passed on to the next generation. When I was born in 1957, my father had to run out at the last minute and buy a crib. He put it together under my grandmother’s supervision. Dad was no mechanic so he was banging his knuckles and pinching his fingers and, in deference to my grandmother, swearing under his breath. “Oh, go ahead and say it out loud,” she said finally. “It’s not like I haven’t heard it before.”)

Mom once described herself to me as having been a “sickly child.” I’m sure she had her share of childhood illnesses, but I could never think of her as having been sickly. As an adult, she weathered the removal of a kidney, survived a flesh-eating bacteria infection that should have killed her, and was a 15-year cancer survivor, even after refusing radiation and chemotherapy. More likely, my grandparents were overly careful with her. She was, after all, hard-won and the only child they were going to have. Even though Mom was suffering from an eye infection at the time, my grandmother’s 1925 letters to Fort Riley indicate more energy than illness. On July 6, the same day the doctor came to strap her ankle, she had trouble reporting the same to Grandpa.

“I can’t have much luck writing,” she said, “with the youngster grabbing everything out of my hands.”

The next day, she wrote, “Frank and Natalie took Margaret for a long ride this evening then she came home, ate and went straight to sleep. She slept all night last night on the sleeping porch—and waked up the minute the sun struck her—about five o’clock! I brought her in at 5:30—she was up parading around her bed by that time. Her eye looks pretty badly tonight but Dr. K says it’s just a bland infection—whatever that means. I’m using boric on it—hope it will be better in the morning.”

Driving, apparently, was as energizing and soothing for Mom as it was for Grandpa. (Decades later, when my father was named Washington Bureau Chief of The New York Times, the only way the paper could get my mother to live in Washington again was to bribe her with a new Mercedes.)

“Your daughter seems well but is powerfully cross,” my grandmother wrote on July 8. “We took a short drive this evening and she enjoyed that immensely.”

By July 11, the eye was looking much better, and Mom’s energy level was peaking.

“She is pulling and slapping me and is on my back at present (I’m sitting on the floor) so if you can read this scrawl you are doing pretty well,” my grandmother wrote, or tried to write. “She hasn’t forgotten you yet. I show her your picture and she says, ‘Da-Da bye’ . . . I can’t write any more—she is yanking the paper out of my hands now.”

At the same time my grandmother was riding herd on Mom, she had begun a more difficult enterprise—convincing my grandfather to let her cut her hair short, like most of the women of her day and age. Grandpa didn’t like the idea at all. He wanted her to maintain the “golden hair of yesteryear” that she had worn from the age of five, when he first met and fell in love with her.

Judging from the tone of my grandmother’s letter of July 7, 1925 they had engaged in a face-to-face fracas over the hair in the days prior to his leaving.

“Nellie Noland [Grandpa’s first cousin] has had her hair cut and she looks perfectly fine,” she wrote in the same letter reporting on Mom’s eye and her ankle. “Ethel [Nellie’s sister] is going to do it this week . . . I am crazier than ever to get mine off. Why won’t you agree enthusiastically? My hair grows so fast, I could soon put it up again if it looked very badly. Please! I’m much more conspicuous having long hair than I will be with it short.”

Grandpa responded that he was surprised by Mom’s eye infection and glad that the ankle felt better. There was no mention of hair.

My grandmother wrote back that Ethel had gone ahead with the haircut and looked great.

“When may I do it? I never wanted to do anything as badly in my life. Come on, be a sport,” she cajoled. “Ask all the married men in camp about their wives’ heads & I’ll bet anything I have there isn’t one under sixty who has long hair.”

On July 9, Grandpa relented.

“Say, if you want your hair bobbed so badly, go on and get it done. I want you to be happy regardless of what I think about it. I am very sure you’ll be just as beautiful with it off and I’ll not say anything to make you sorry for doing it. I can still see you as the finest on earth so go and have it done. I’ve never been right sure you weren’t kidding me anyway. You usually do as you like about things and that’s what I want you to do.”

It was a heartfelt and beautifully written capitulation, but it didn’t get to her fast enough. In a postscript to her letter describing how Mom was pulling and slapping at her, she wrote: “What about the hair-cut?”

Finally, Grandpa’s letter arrived and was so “dear” that “it almost put a crimp in my wanting to do it,” she said. “But if you know the utter discomfort of all this pile on top of my head and the time I waste every day getting it there you would insist upon me cutting it. I most sincerely hope you’ll never feel otherwise than you said you do in that letter for life would be a dreary outlook if you ever ceased to feel just that way.”

The next day, she was asking his advice on having it done, mentioning an “expert women’s barber” in the Baltimore Hotel. “Mrs. Berry [wife of the teeth-pulling, golf-playing dentist] went to him yesterday and Natalie [married to my grandmother’s brother Frank Wallace] says her hair looks better than it ever has.

“Natalie and Frank,” she added, “are getting real peevish on the subject of bobbed hair. She is as crazy as I am to have it done, but Frank is so grouchy about it.”

“Don’t you worry your pretty hair anymore, go and cut it off and please yourself,” Grandpa reiterated. “As I said before you’ll be just as beautiful to me if you have those curls I’ll never forget or if you have none at all. It’s you I’m in love with not what you’re made of.”

From then on, it appears, she didn’t believe him.

August 15: “The hair is still intact, but I wish it were not.”

Also August 15, separate letter: “Why do you so studiously avoid the subject of hair-cutting? Did I tell you that Ethel had Lisle do hers? She said every man she knew in town came into the barber shop while she was having it done.”

Finally, August 16: “Ethel and Nellie still look grand with their short hair.”

The campaign for a haircut was the only bit of politics mentioned in July of 1925. Grandpa had lost his reelection bid for eastern judge of Jackson County and was selling memberships in the Automobile Club of Kansas City, which earned a good income and was perfectly suited to his love of cars and driving. That year he also took evening classes at what is now the School of Law at the University of Missouri, Kansas City. He gave them up in 1926, after his election as presiding judge (county administrator), because he said he couldn’t concentrate with all the office seekers sidling up to him during class.

Normally, my grandmother took an avid interest in his political life. She understood the game and provided Grandpa with an excellent sounding board and go-between. By 1937, when he was a junior senator investigating the looting of the U.S. railroad system, she was reading the Congressional Record regularly and taking potshots at President Roosevelt.

“I hope you make a point of finding out exactly where Mr. R. and J. M. Farley stand on K.C. politicians if you can depend on what they say,” she would write to Grandpa in Washington on November 16, 1937, referring to the President’s backing of a major rival, Missouri Governor Lloyd Stark. “Because if they think they can get along without us in ’40, we’ll show them a thing or two.”

In 1923, at the start of Grandpa’s political career, she stood in for him when he was off with the National Guard, passing along newspaper clippings and requests from constituents.

“Another woman wanted her road oiled this morning,” she reported on July 23, 1923. “She lives on Hodges Avenue. Said she has hay fever and the dust is just killing her.”

Most roads of the day were dirt. You sprayed oil on them to keep down the dust which, during the hot, dry July of 1923, must have been blowing everywhere, likewise the housewives. My grandmother seemed to feel it was a conspiracy.

“Just one woman has hollered about roads this week,” she wrote in exasperation on July 26. “All of these women who have called up live out around Bristol and Maywood. I think they must have a league out there.”

Jackson County’s deplorable dirt roads were actually high on Grandpa’s administrative to-do list. As a farmer and as my grandmother’s suitor, he had spent years bouncing over them. During the campaign for eastern judge in 1922, he traveled the county with a couple of bags of cement in the trunk of his Dodge roadster so the car wouldn’t pitch him through the windshield. He would ultimately make his reputation as presiding judge of Jackson County, in large part, by improving the roads.

In between the politics and concerns over health and haircuts, my grandmother found time to joke and tease. In her first letter to Grandpa after he took off for Fort Leavenworth in 1923, she tweaked him about his trip and eventual dinner in Tonganoxie with Bill Kirby and Jean Settle.

“How did you like playing around with another lady today?” she wrote. “Did you and the fair Jean have a good time?”

She teased him about his vanity, too. Showers at Fort Leavenworth were down the street, cold, and fast. Grandpa was a bit of a clotheshorse, particular about his appearance, and normally accustomed to taking his time over his morning routine.

“I am up at 5:15 again this a.m. 30 minutes before reveille so I can write this letter,” he wrote on his second morning in camp in 1923. “We have a schedule now. Get up at 5:45, fifteen minutes for the bend overs [exercises], shave, bath and breakfast at 7:00 then duty at 7:30.”

Reading that, my grandmother assumed he meant he had 15 minutes for the whole shebang, not just the exercises.

“Don’t you want your bath-slippers?” she wrote back the next day. “I should think you’d need them traveling down the street to your bath every morning. I’d like a picture of you shaving bathing and dressing in fifteen minutes.”

Sometimes, she just found things funny.

“The Swifts got off to Colorado early yesterday morning,” she wrote on July 17 about the departure of her neighbors, who were going on vacation. “He started that old car right on the dot of five o’clock—and I lay there in bed and watched them get ready. I wouldn’t have missed seeing Mrs. Swift in knickers for a hundred dollars.”

Most of all, she worked hard at the simple act of communicating with the man she loved. Of all the letters they wrote back and forth, only a few don’t mention actually writing letters.

“I just had your Thursday letter,” she wrote on July 19, 1923. “Had been sitting at the front window waiting for the postman for hours.”

He came right back with: “I sure raised sand with the adjutant yesterday morning when I didn’t get a letter, but it came in the afternoon and boy! how nice it was.”

They rose early and stayed up late to write. Letters even invaded my grandmother’s dreams.

“I was powerfully glad to get your special late last night,” she wrote on July 21, 1923. “And then I dreamed that I got still another one, which was very nice as long as it lasted.”

If my grandmother missed sending a letter, her excuse was thorough . . .

“I was so delighted to get that ‘special’ this morning. It made me sick not to have sent yours that way yesterday, but there wasn’t anybody here who could take it to the P.O. (Frank and Fred were both gone all day) and I just felt like I could not make it up town and back and I didn’t have enough stamps at home. Sorry as I can be that you won’t have even a piece of a letter today for I know how much I would have missed mine.”

. . . or interesting.

“It was so blazing hot last night I didn’t have the nerve to keep on enough clothes so I could have a light long enough to write a letter.”

But there were few excuses. She couldn’t go for very long without touching base and telling him how she felt.

“Lots and lots of love and please keep on loving me as hard as ever,” she ended the last letter to him at the end of his July 1925 encampment. “You know I just feel as if a large part of me has been gone for the last ten days.

Devotedly,

Bess”

Clifton Truman Daniel is the oldest grandson of President Harry S. Truman and is currently director of public relations for Harry S Truman College, one of the seven City Colleges of Chicago. He is also honorary chairman of the board of the Harry S. Truman Library Institute. A frequent speaker and fundraiser, he is author of the 1995 book, Growing Up With My Grandfather: Memories of Harry S. Truman. His article “Adventures with Grandpa Truman,” appeared in Spring 2009 Prologue.