“I Wish to Acknowledge . . .”

Fall 2009, Vol. 41, No. 3

By Jason R. Baron, Jeffery Hartley, and Ezequiel Berdichevsky

The names Claudia Anderson, Walter Hill, Michael Musick, Timothy Nenninger, Trevor Plante, John Taylor, and Steven Tilley, may not be as well known as some famous historians. But in the words of the New York Times’ Maureen Dowd—writing about NARA in another context—each of these archivists, and many more colleagues, are "macho heroes" in his or her own right.

They've been acclaimed for providing "invaluable assistance," being "especially helpful," serving as a "friendly and exceptionally knowledgeable guide," offering "wise suggestions and extraordinary assistance," acting as a "patient and assiduous pathfinder," and cited as proof that "the taxpayer is getting a good deal."

But even if the names aren't familiar, you've seen and admired their work.

That is, if you've read some books by well-known historians like Michael Beschloss, Rick Atkinson, David McCullough, Robert Caro, Douglas Brinkley, or Robert Dallek. Or even less famous authors like DeAnne Blanton and Lauren M. Cook, Jon T. Hoffman, and Edgar Leo Anderson. The compliments are from people like them.

Taylor, Plante, and the others are or were staff archivists at the National Archives to whom these noted historians, some of them Pulitzer Prize–winners, have turned for guidance and help when they were researching their books, many of which are now "must" reading for students of history.

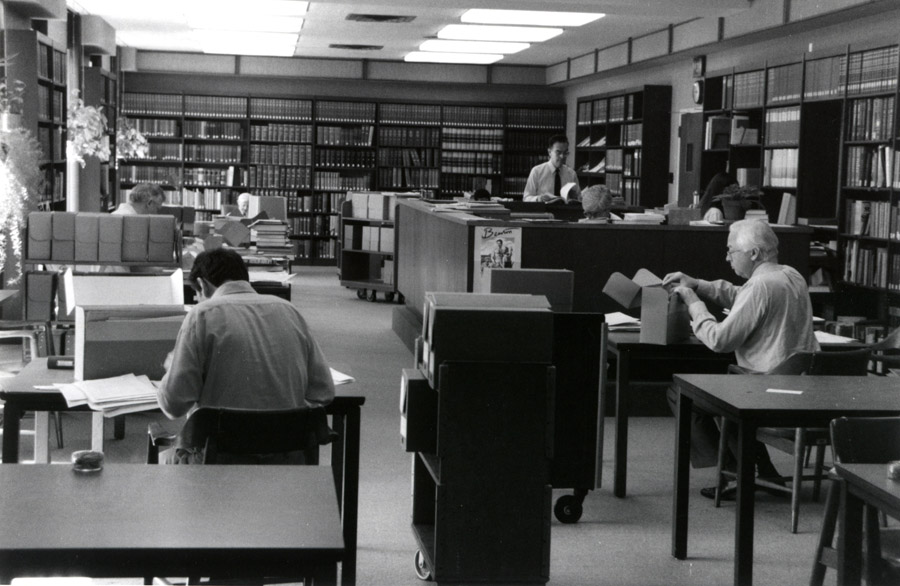

These names are but a few of the hundreds of archivists, past and present, who work with authors and researchers every day to search the vast holdings of the National Archives nationwide—in Washington, D.C., and College Park and at regional archives and presidential libraries around the country. They help historians pursue the information they need to add new layers and new details to the story of America and its people.

Occasionally, the archivist heavily influences the outcome of the research and the book that results; more often, he or she plays an important role in guiding the historian through the winding, and sometimes little-traveled, path through NARA's holdings. Sometimes authors thank these archivists by name and at other times they merely cite the "staff at the National Archives" or at a presidential library or regional archives.

Two-time Pulitzer Prize–winner McCullough summed up his feelings about the staff at the Truman Library in his acknowledgments in Truman, a biography of the 33rd President: "There is no part of this book in which they have not played a role, both in what they have helped to uncover in the library collection and in what they themselves know of Truman's life from years of interest and study."

Vincent Bugliosi, writing in Reclaiming History: The Assassination of John F. Kennedy, noted that there was no way the book could have ended up being what it turned out to be "without the wonderful cooperation" he received from Tilley, who is director of the Textual Services Division in the Access Program Unit of the Office of Records Services at NARA, as well as NARA archivist James Mathis.

Bugliosi's requests for large amounts of documents were continuous, the author recalls. "I kept wondering whether I'd soon be getting a letter from Steve or one of his assistants, saying, ‘Vince, please. Enough is enough,’ but I never did. What I always got, never accompanied by a complaint, was a very large envelope in the mail containing everything I had requested."

Tilley says he has "always gotten satisfaction from reference service, in providing help and guidance to researchers who came to the Archives for that help." He adds, "It is a sense of satisfaction in knowing that the author felt that my efforts were beneficial for the book or article, whether or not I agree with the conclusions reached." And that, he says, makes the job "interesting and worthwhile."

For 75 years, NARA archivists have found themselves key links in the writing of American history, providing valuable guidance, expertise, and assistance to thousands of authors looking to assemble the story of a particular aspect of the American experience.

"Historians rely heavily on archivists to orient them to new archives, to identify information not easily accessible, and to discover the research value of particular collections," wrote Catherine A. Johnson and Wendy M. Duff in "Chatting Up the Archivist: Social Capital and the Archival Researcher," in the Spring 2005 issue of The American Archivist.

This article goes on to trace the often underappreciated symbiotic relationship wherein archivists build up "intimate knowledge" of historical sources and help direct historians to sources and subjects that they would not have thought of on their own. In those cases, the archivist’s intimate knowledge, what Duff and Johnson term his or her "strong mental image," of a collection’s holdings becomes essential. Without that knowledge,critical sources would otherwise be overlooked. Similarly. Elsie Freeman Finch, in her book Advocating Archives, describes how the archivist plays multiple roles, simultaneously acting as "servant," "gatekeeper," and "partner" to the historian.

Civil War expert Plante says working with historians makes him a better archivist.

"I really enjoy talking to historians about the latest books that have come out on various topics to get their opinions of the books," he says. "I enjoy the back and forth conversation that takes place, of their telling me about books I was unaware of and vice versa. The conversations with historians definitely help keep me up to date in the field as I usually end up reading their recommendations, be it books on Civil War history or military history in general."

At the National Archives and Records Administration, archivists develop their "strong mental image" of a certain collection from the moment records are transferred to NARA for permanent storage.

Traditionally, records have come to the Archives in boxes from their originating agency, which has honed the shipment down to its most important records. Overall, only about 2 to 3 percent of all records generated by the federal government are deemed important enough to be permanently archived.

Depending on where an archivist works, he or she may be responsible for helping with the initial accession of the records, the review of those records, and the development of finding aids for those records. As a result, the archivist develops a comprehensive knowledge of the particular accession he or she is working with, such as records relating to a particular government function (e.g., foreign relations), stored in a particular medium (e.g., still pictures), or originating in a particular branch of the government (e.g., the Department of Commerce).

Archivists at locations all around NARA have been doing this for years. Although authors who have benefited from their work often acknowledge them in the final product, archivists view helping these authors as simply part of their job as steward of certain valuable records belonging to the people of the United States of America.

For example, Timothy Nenninger, who is chief of the reference section at the National Archives at College Park, receives plaudits from military historians. In Corps Commanders of the Bulge: Six American Generals and Victory in the Ardennes, Harold Winton writes that Nenninger "is an important asset to the study of military history in this country and a true friend to those who practice the craft."

Jon T. Hoffman in Chesty: The Story of Lieutenant General Lewis B. Puller, writes that Nenninger "performed his usual sterling service in unearthing boxes of records that otherwise seemed buried forever" and also cites archivist Richard Boylan for having "worked similar miracles" at the Washington National Records Center in Suitland, Maryland.

Both Robert K. Griffith, Jr., in Men Wanted For the U.S. Army, and Kathleen Broome Williams, in Grace Hopper—Admiral of the Cyber Sea, tell stories of Nenninger’s efforts to find new documents inspiring them to go on after these authors were "ready to give up" and "hit brick walls," respectively.

And Pulitzer Prize–winning historian Rick Atkinson’s The Day of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy, 1943–1944, begins with a tribute to Nenninger that reads: "Virtually every page of this book bears Tim's imprint, and I am deeply grateful for his expertise, humor, friendship, and willingness to read a portion of the manuscript."

Working with people like these, Nenninger says, is not difficult because they were already knowledgeable about their subject, had realistic expectations about working with archival records, understood that NARA doesn't have everything, were receptive to advice, guidance, and direction—and "were not in a hurry."

These types of researchers account for less than 30 percent of on-site researchers, while most researchers are looking for something "pretty specific and easily identifiable," he said.

Then there's the late John Taylor, for whom Nenninger once worked. Taylor was an institution unto himself during his six decades at the Archives and is mentioned in the prefaces and acknowledgments of countless books dealing with World War II, the Cold War, and the history of espionage over that period.

Michael Dobbs called him an "inexhaustible fount of information on World War II" in Saboteurs: The Nazi Raid on America. John Costello and Oleg Tsarev's acknowledgments section in Deadly Illusions referred to him as the "paradigm for all historical researchers," while Beschloss in The Conquerors referred to him as "redoubtable."

In 50 Days of War and Peace: July 16 to September 3, 1945, or Why Harry Dropped the Atomic Bomb, Edgar Leo Anderson recounts how Taylor gave him "the impetus to persevere over the years and complete the manuscript."

Iris Chang called Taylor "a friend and cherished fixture at the National Archives for more than half a century" and "one of the best allies an author could hope for," in The Chinese in America: A Narrative History. Chang further described Taylor as "compassionate," "profoundly wise," and "endlessly helpful," and credited him with playing a "special role" in the research of her book.

In Allen Dulles, Gentleman Spy, author Peter Grose notes, "I am only the latest in a long line of researchers to recognize a unique national resource in the person of John E. Taylor, who valued the fundamental freedom of information long before it became recognized in law."

Perhaps Edward S. Miller's acknowledgment in Bankrupting the Enemy: The U.S. Financial Siege of Japan before Pearl Harbor expressed it most succinctly when he called Taylor a "national treasure." One student intern reportedly put it simply: "Mr. Taylor knows everything."

The late Walter B. Hill, Jr., who was a senior archivist and subject area specialist in African American history, was cited often. Hill was described by Gerald Horne, author of Black and Brown: African Americans and the Mexican Revolution, as someone who not only provided "extraordinary assistance" on the writing of the book, but had also "become a good friend."

Other historians, such as Jeffrey Bolster, offer poetic tributes. In Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail, Bolster thanks Hill, John Vandereedt, and Aloha South as "archivists who steered me through the shoals of their collections." Hill provided guidance to many individuals researching African American history with his finding aids and guides to records pertaining to African Americans at the Archives.

Abraham Lincoln and Civil War–Reconstruction scholars have found much help at the Archives. In They Have Killed Papa Dead: The Road to Ford's Theater, Abraham Lincoln’s Murder and the Rage for Vengeance, Anthony Pitch thanks a host of archivists by name, but reserves his most interesting praise for Plante.

He notes that it was Civil War specialist Plante who "unwittingly" led him to "the discovery of an unpublished letter from Samuel Arnold asking Secretary of War Edwin Stanton for a job three months after he had agreed to help Booth kidnap Lincoln."

Pitch notes that after he "had told Plante [he] was on the lookout for correspondence from prisoners on the island garrison of Dry Tortugas," Plante suggested that Pitch look at records in the Office of the Quartermaster General. Shortly thereafter, Pitch "stumbled upon Arnold's sensational letter."

Plante and fellow Civil War expert Musick were singled out by Drew Gilpin Faust, who was a dean at the Radcliffe Institute working on a book, The Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War. Plante, she said in a Prologue interview last year, helped her dig out the stories of casualties during the Civil War. Musick greeted her on one of her visits to the Archives, with a couple of boxes of records, and the comment: "This will interest you."

Plante cites the relationship he developed with Faust while working on the book as typical of those that develop between authors and archivists who work together over longer periods.

"One of the things I enjoyed most about working with Dr. Faust was that after our initial meeting, in which we discussed several secondary sources such as books and articles on death, dying, and burial in the Civil War, she sent me several articles that she had written on the subject," Plante recalls "It's not every day that a hard-working historian takes time out of her busy day to send an unsolicited and unexpected package to an archivist."

Musick's expertise on the Civil War is known far and wide. Blanton and Cook singled out Musick, now retired, in They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the American Civil War, where they noted that he "knows more about the Civil War and its sources than anyone else on earth." In The Army of the Potomac: Birth of Command, November 1860–September 1861, Volume I, Russell H. Beatie stated that Musick's "willing assistance is truly encyclopedic and always available." Musick was also cited by Thomas P. Lowry in Confederate Heroines as "legendary" and providing various good suggestions to make on alternative sources of records—without the use of a Ouija board—when the author's "séance with one of the Old Army consultants" left the subject of his work "still lost in the mists of time."

Another Civil War author, Tom Wheeler, recounted the unique "aha" moment he had at the National Archives that inspired him to write Mr. Lincoln's T-Mails: The Untold Story of How Abraham Lincoln Used the Telegraph to Win the Civil War. Wheeler found himself standing with a "half dozen other people amidst the miles of files in the vaults," as military records archivist Rick Peuser showed "a book of glassine pages, each of which contained a handwritten telegram in the precise, forward-leaning cursive of Abraham Lincoln." As Wheeler "turned the pages in awe," he proclaimed ‘These are Mr. Lincoln’s T-Mails.’"

Also known for expertise on a particular subject is Claudia Anderson of the Johnson Library. But few tributes to NARA archivists can match what Robert Caro said about Anderson in his Pulitzer Prize–winning work, Master of the Senate, the latest and the third of his four volumes on the life of President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Caro notes that the title "senior archivist" fails "to do her justice." She has "made it her business to know" the materials in her charge "as thoroughly as it is possible for a single human being to know these thousands of boxes of documents." Caro goes on to praise her commitment to access, in the sense that she wants historians to know said material, her "rare integrity and generosity of spirit," and ends his encomium by stating that he cannot imagine "any biographer who owes her more."

Presidential library staff also have received numerous heartfelt plaudits to staff, named and unnamed alike. Arnold J. Rotter in his Comrades at Odds: The United States and India, 1946–1964, writes that the Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy presidential libraries received him "with a spirit of generosity and a willingness to help that still takes my breath away."

Adam Cohen, author of the recent work Nothing to Fear: FDR's Inner Circle and The Hundred Days That Created Modern America, states his "enormous thanks to the staff of the Roosevelt Library Presidential Library . . . who do a laudable job of tending to the New Deal flame." Robert Dallek in his An Unfinished Life: John F. Kennedy, 1917–1963, praises the Kennedy Library's staff as "essential." Author Gary Dean Best, writing in Herbert Hoover: The Post-Presidential Years, stated that the staff were "unfailingly helpful" and that working there was a "delightful experience."

Not every author or researcher who avails himself or herself of the expertise and time—sometimes quite a bit of both—of a NARA archivist acknowledges that help in the book, and sometimes there will be effusive praise from authors that the archivist can’t remember.

Sometimes archivists get mentioned for special kinds of things they do or provide for the authors.

For example, in Democratizing the Enemy: The Japanese American Internment, Brian Masaru Hayashi notes that NARA archivists, including Aloha South, Larry McDonald, William Mahoney, David Pfeiffer, and Barry Zerby, challenged him "to inspect alternative sources" that he initially did not consider and "widened [his] horizons substantially."

Michael L. Krenn, in Black Diplomacy: African Americans and the State Department, 1945–1969, writes that Regina Greenwell of the Johnson Library "pointed me to several collections I might have overlooked and never blinked an eye at in my hundreds of declassification requests." Similarly, Michael Long's publication of the Civil Rights Letter of Jackie Robinson recognizes a debt "to Paul Wormser of the National Archives in Laguna Niguel, California" for encouraging the author "to take a look at the Jackie Robinson file in Richard Nixon's pre-presidential papers."

And Dobbs, in his book Saboteurs, begins his acknowledgments by saying he'd "particularly like to thank Greg Bradsher, who whetted my interest in the case by giving me a tour of the stacks."

In Hitler's Last Chief of Foreign Intelligence: Allied Interrogations of Walter Schellenberg, Reinhard Doerries captures the occasionally tense dynamic between driven researcher and patient archivist. Doerries not only gives thanks for the "ceaseless efforts" of Nenninger, but also explains that Boylan and Bob Wolfe "never lost patience when I was impatient and surely unkind under the pressures of research."

Author David Nichols's A Matter of Justice, about the history of civil rights in the 1950s, states that staff at the Eisenhower Library, particularly then-director Dan Holt, "encouraged the project at every junction, and archivist David Haight's encyclopedic knowledge and uncanny ability to find obscure documents made all the difference."

Erika Lee, author of At America's Gates, a book on Chinese immigration policies, said that writing her book was "made even more enjoyable by the camaraderie and valuable assistance" provided by "Neil Thompson, Waverly Lowell, and the entire staff of the National Archives, Pacific Region, in San Bruno," who "generously shared their own findings, greatly facilitated my research, and provided a second home to me."

Edwin Black's timely study of the oil crisis, Internal Combustion, praises NARA Great Lakes Region archivists, specifically Donald Jackanicz, Martin Tuohy, Scott Forsythe, and Peter Bunce for performing "miracles." Black notes that after these archivists discovered that "they held crucial forgotten court records," he called one day at noon and raced to the airport where "the next morning more than a dozen boxes were waiting on trolleys."

In his book about Betty Ford, Candor and Courage in the White House, John Robert Greene noted that "Writers only write alone. . . . Indeed, one of the greatest pleasures of any writing project is to freely admit that there is a list of names without any of whom this book could not have been written." He goes on to mention Dennis Dallenbach, David Horrocks, Helmi Raaska, William McNitt, and Nancy Mirshah, of the Ford Library, who "went far beyond the call of duty in helping me track down the photos that add to this book."

Martha Gardner, author of The Qualities of a Citizen: Women, Immigration, and Citizenship, 1870–1965, was grateful to staff archivists Waverly Lowell, Neil Thomsen, and Robert Ellis for being allowed "to rummage through the records of countless immigrant women."

Kenneth D. Ackerman, in Young J. Edgar: Hoover, the Red Scare, and The Assault on Civil Liberties, a book about the 1919–1921 Palmer Raids to round up suspected radicals, thanks archivists Fred Romanski and Alan Walker, who "came through for me time after time when I needed help in deciphering the complex systems of records from the era."

In The Burning of Washington: The British Invasion of 1814, Anthony Pitch provided the prototypical acknowledgment to an archivist when he expressed his gratitude to archivists Rebecca Livingston and Rod Ross for "plucking dusty files from sheltered safekeeping."

And James W. Hurst extolled NARA archivist Mitchell Yockelson's "vast knowledge" of archival holdings in Pancho Villa and Black Jack Pershing: The Punitive Expedition, while recounting the role Yockelson played in answering e-mail queries, telephone calls, and "digging out the boxes and boxes of documents."

Perhaps the strangest acknowledgment was written by author Andrea Tone, whose Devices and Desires: A History of Contraceptives in America recounts that the topic "imposed research challenges that might have been insurmountable were it not for the expertise, support and timely intervention of numerous archivists and scholars."

Tone goes on to thank Aloha Smith, for guiding her through postal records in Washington, D.C., as well as Tab Lewis who "located Federal Trade Commission transcripts—and registered appropriate combinations of enthusiasm and alarm when decaying diaphragms and condoms appeared glued to the transcript pages!"

This brief sampling of citations does not do justice to the hundreds of extraordinary members of NARA’s archival staff who have been similarly mentioned in books not recounted here. In recent decades, acknowledgments sections have become more fulsome.

But there are notable examples from a half-century ago. When Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., took the time in 1957’s The Age of Roosevelt: The Crisis of the Old Order, 1919–1933, to express "special acknowledgment" to Herman Kahn, then director of the Roosevelt Library, for demonstrating "with spectacular success how a library can serve the cause of scholarship," this was indeed an exception to the practices of the time.

And finally, author R. A. Ratcliff's words in Delusions of Intelligence: Enigma, Ultra, and the End of Secure Ciphers, while giving special praise to retired NARA archivist Timothy Mulligan, have special import as NARA (and all of government) finds its way in the future, awash in all manner of new forms of records on electronic media, residing side by side with vast and still growing collections of textual holdings:

The use of technology in archives has improved the researcher's lot tremendously; but no technology, however advanced, can provide a researcher with the depth of information . . . and numerous gentle nudges toward crucial documents that [he] has provided for more than a decade. Archivists such as he are a national resource, and they are retiring unreplaced. In the midst of its rush to acquire all things electronic, NARA's administration should not neglect this most valuable resource of all.

In fact, NARA is not neglecting this "valuable resource" known as the archivist, even as its lurches into the future of electronic records that will be available to anyone, anywhere, anytime via the Internet. The Archives has in the past few years hired a number of new archivists and given them intensive training in handling both traditional paper records as well as electronic records of all forms that are now being created by the federal government.

Sometimes the work of the archivist is so important it leaves the author wondering what Gabor Boritt asked in The Gettysburg Gospel: The Lincoln Speech That Nobody Knows: "[H]ow does one thank a learned archivist who finds precious items a researcher cannot locate and who, after a long exhaustive day of work, stays well beyond closing time to help? How?"

Ultimately, archivist Plante says, it doesn't make any difference whether the author thanks him or not. "I know that I have contributed to several books, some whose authors have thanked me, and others who have not," he says. "I know that I assisted them in the research they conducted which led to their final product, so I feel like I helped them in writing the book."

Many more acknowledgments deserved inclusion in this piece but could not be included due to space limitations in the printed edition. This online addendum lists acknowledgments to NARA and staff members in fuller form.

Jason R. Baron has held the position of director of litigation in NARA’s Office of General Counsel since coming to NARA in 2000. He holds degrees from Wesleyan University and Boston University School of Law.

Jeffery Hartley is chief librarian for the Archives Library Information Center (ALIC). A graduate of Dickinson College and the University of Maryland's College of Library and Information Services, he joined NARA in 1990.

Ezequiel Berdichevsky is an assistant general counsel at the National Archives. He is a graduate of the University of Maryland, the University of Michigan, and The George Washington University Law School. He has worked at NARA since 2007.