Herbert Hoover’s Boy Biographer

Fall 2007, Vol. 39, No. 3

By Glen Jeansonne

© 2007 by Glen Jeansonne

In the dismal days of the Great Depression, one 11-year-old boy, quite precocious, yet expressing the innocence and insight of youth, did not lose his ideals or his admiration for the much-reviled President, Herbert Hoover.

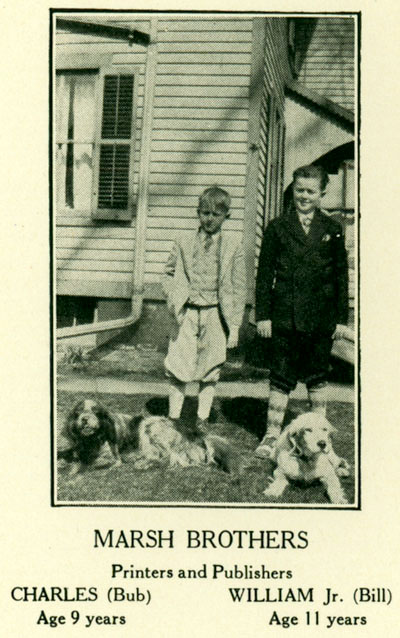

Buried in the archives of the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and in faded clippings found in the library's newspaper clipping files is a brief biography of the beleaguered President by William J. Marsh, Jr., of New Milford, Connecticut, assisted by his nine-year-old brother Charles ("Bub"). For a few weeks the book created a sensation in major dailies. The most intensive coverage appeared in the New York Herald Tribune, but there were stories in the New York Times, the Washington Herald, and the Washington Post.

Marsh did not share the nation's antipathy toward its chief executive. Nor did he march to the downbeat tempo of the time. Rather, he was inspired by Hoover's example and his fortitude and had pride in his country and in the religious values he absorbed.

Like some of the most famous objects of art and scholarship, Our President Herbert Hoover occurred almost by accident. One day while rummaging through items his father, an antique dealer, had accumulated, Billy found a printing press his dad had bought for 50 cents. He tinkered with it until it worked and decided to start a printing business. Billy hired a boy to help him at 25 cents a week, but his hired hand proved lazy. So Billy employed his younger brother Charles at 10 cents a week, plus a small commission. Billy was a sharp businessman. Charles was not much more energetic than the first boy; he preferred to write music, aspiring to become a composer.

Then Billy, who thought big, decided there would be more money in writing and publishing a book rather than printing work for others. He wanted a big topic. Really big. He decided to write a book about President Hoover. Billy condensed the President's life into 44 pages of fifth-grade language and injected sermons about clean living and moral advice. He tended to digress but always returned to Hoover. Billy found Hoover fascinating and did not blame him for the Great Depression. To him the President was the greatest man in the world, belonging in the company of his favorites Washington, Lincoln, and Coolidge.

Marsh wrote the biography in six months, making rapid progress during a four-week period when he had time off from school. His research included newspapers, Hoover's radio addresses, and information from his parents. The book was illustrated with old woodcuts scrounged from the local print shop, most of them demonstrating a moral lesson. Jessie B. Rittenhouse, a professional writer, wrote an introduction. The study, she wrote, was a "remarkable performance for a boy of 11 years. It demonstrated an intuitive sense of drama and the picturesque." Moreover, the young author was an accomplished storyteller who related Hoover's life with zest. "The book reflects the child's point of view and is in the naïve phraseology of a child, which makes it authentic." She found humor in the book and concluded that it moved at a brisk pace.

Billy enjoyed a sense of accomplishment. "I know if my press could talk, I am sure it would say 'William Marsh, I am proud to be able to print a life of Herbert Hoover.'" The study was not pretentious. "I hope you will enjoy reading my book," Marsh indicated. "I have tried very hard to explain his life so you would all understand. There are other things I would have liked to have written about, but I didn't understand it well enough to write about." Billy was, however, a commercial publisher. "I expect to do a big rushing business," he predicted. The boy biographer printed 60 copies at a cost of 50 dollars, and quickly sold them. The originals were handsome, printed on blue paper, bound in cloth, with gold lettering on the cover. He saved a special copy, printed on blue vellum, for the President.

Marsh was a patriotic moralizer who frequently departed from his account of Hoover's life to inject observations about his personal beliefs, family, the state of the country, and his aspirations. The book opened not with Hoover's birth but with an essay on "Our Flag" illustrated by a photograph of Billy Marsh holding a small American flag. Billy explained the origin of the flag, how it had inspired our soldiers in the American Revolution, and concluded that no other nation's flag could compare with "Dear Old Glory."

The chronology of Marsh's book is loose. He rambles, writes colloquially, and skips over many aspects of Hoover's career. Considering the diatribes being written about Hoover by adult journalists in 1930, however, the boy's intellectual honesty is refreshing.

On page eight, Marsh gets down to the main story—Hoover's rise to the presidency. Hoover's father, he wrote, was a blacksmith, "as most men in his day were." Billy explained that the Hoovers were a family of modest means. "Of course, we all know, a person would never become rich from shoeing horses, as horses don't need to be shod every week." Hoover had an older brother, known as Tad, and a younger sister, called May. "I don't know anything about his sister, but; I can say this, I think she is a very lucky girl to have a brother like Mr. Hoover."

Young Hoover loved to sled down the hills in West Branch, Iowa, the Quaker village in which he was born, Marsh explained, "and if the sled happen to just slide out from under him, he done just what all we boys like to do, go down on the seat of his pants. It is not very good for the pants, especially if they are new." Marsh's favorite spot was the muddy pond where Hoover and his pals swam. "I think his greatest sport was swimming. The old swimming hole which I have read so much about must be a great place. I sure would love to see it, and some day, if I make good as a writer, I intend to go see his old home and the swimming hole, and then I am going to write a book on it."

Hoover began fishing as a boy and never quit. "From what the papers say, Mr. Hoover can't be beat when it comes to catching big fish." Hoover's father died when he was barely old enough to remember him, and his mother became a preacher. Hoover had a good education in the elementary school at West Branch. "Our country is noted for its fine public schools, and my way of thinking is, that we have the best public schools in the world, and there is no excuse for anyone saying, I can not afford to send my children to school."

Then the Hoover children's mother died, and Billy reflected on how sad that must have been. "There could be no replacement for their mother; for there is no one in this world who can take her place. Mother sees our jokes, she will laugh with us, she is sad with us. It is our mother who teaches us our prayers, who tells us right from wrong, she teaches us love which means God and sends us to church and Sunday School."

Marsh digressed to moralize about the importance of family. "A good mother don't spend her time at dances and parties, she spends her time teaching her boys to be good, she helps them with their school work, she makes their home a happy one." Fathers also play a crucial role. "My Dad is a good all around sport to us boys, and I tell you it is great, when you know your boy friends are always welcome regardless of a little mud on their shoes."

Billy admired Hoover's work ethic. "At night the boys carried in the wood and milked the cows," he wrote. But they found time to play and "had an all around good time. I suppose they had a horse, for I guess all farmers do; and if they did, they must have had lots of sport riding. I know I wished I lived on a farm so I could own a horse."

In Oregon, where he went to live with his Uncle John Minthorn, his mother's older brother, Bert's chores were more varied than at West Branch. "Of course, it is better for both boys and girls to have a certain amount of work to do as all play and no work is not good for anyone," Marsh explained.

Hoover also became a reader in Oregon, where Uncle John was more liberal in what he let children read than Bert's parents had been. Reading, hard work, and education were the keys to success, Marsh explained. "If a boy makes up his mind he wants to do a certain amount of work, and if he is a hustler he will succeed." For example, Bert had to take the Stanford admission exams twice before he was admitted. At Stanford, he met his future wife, Lou Henry, who had heard about him and was anxious to meet him. "Do you know girls are very curious just mention a fellow's name a few times, and you are sure of getting the girls interested."

After graduating, Hoover could not find an engineering job, so he accepted menial labor as a miner. "When a boy or man really wants to make something of themselves, they don't shun dirty work," Marsh wrote. "It isn't always the man who is dressed up that has the brains; for I know some men, that I think are without good brains, but still they are dressed up and think they are something, and I know if these men had to make a living, they wouldn't have sense enough to know how to go about it."

Through pluck and industriousness, Hoover became a successful mining engineer. Then he saved Belgium from starvation. The British were impressed and wanted to knight him. "England wanted him to become a 'Sir,'" Marsh wrote. "And he said, 'I guess not, I don't want to be Sir Herbert Hoover.'" Hoover preferred to remain an ordinary American citizen. "Now that is what I call a real man," Billy declared.

Marsh praised Hoover's love of children. "Can you imagine millions of children starving to death, a little child is not like a grown person, they as a general rule, depend on the older people for help. What would they have done without his help?"

Like Hoover, the boy author abhorred war. "Countries are just like a gang of boys," he wrote, "there is always one fellow in the crowd who wants to be boss." He said his mother would not let her children even play war.

Billy Marsh respected the chief executive. "Herbert Hoover has done a lot of good for this country," he wrote. He disagreed with adults who felt Hoover was an ineffective radio speaker: "His speeches over the radio were interesting, even a child could understand them." Billy told his readers that he stayed awake all night listening to Hoover speak on the radio and could barely walk to school the next morning. Moreover, "He never said one mean thing about the man who was running on the Democratic Ticket." Marsh admitted he was only a boy and adults sometimes dismissed his opinions as meaningless. "Kids have better ears than you think for," he claimed. "Every time I heard any one say something mean over the radio about Mr. Hoover, I made up my mind, right then, that they either didn't know much, or they had poor bringing up."

Hoover was a great American success story. "He is numbered with all our great men, he is like Abraham Lincoln, a self-made man." Billy believed that boys should save their money for college and join wholesome organizations such as the Boy Scouts and YMCA. He was vice president of the Junior League of his church. Loose living was not for him. "I am not allowed to gad the streets at night, my brother and I can have all the boys we want at home, and my Dad helps to entertain them, and we sure have some good times." Liquor wasted bodies and money, and he strongly supported Prohibition. "Shame on you parents who want to feed your boys and girls wine and beer," he admonished. "And let me tell you mothers, if you didn't smoke so many cigarettes, it would be more to your credit."

Marsh said that now that his book was complete he wanted to meet Hoover, a "wonderful man," who "holds the highest position in the world." The young biographer wrote only briefly about the crash and Depression, stating they were not Hoover's fault. A senator who criticized the President "ought to be ashamed of himself. I think it is awful to talk about our President." The senator must have run out of anything to say, Billy concluded. Hoover was "a good man, and everybody knows it." Further, it was a fine idea to have a peace-loving Quaker as President. "If we are at Peace with God, we are very happy and contented, it keeps us out of trouble."

The chief executive was pleased to learn about the 11-year-old's flattering biography from a front-page article in the New York Herald Tribune. He told the Tribune he was eager to obtain a copy. Once the Tribune hit the newsstands, the jaded literary community in New York and Washington sizzled. The biography seemed to strike a chord because it differed dramatically from the debunking of Hoover that dominated the press.

Almost immediately, four large New York City publishing houses cabled the Marsh home urging the young biographer not to sign a contract until he spoke with their representatives. The competition heated up. The publishers were attracted by the audacity, unspoiled outlook, and lack of cynicism of the young author who seemed a model citizen. Billy had the foresight to promote his own book. Presumptuously, he mailed a copy to the Herald Tribune. Billy announced that he had printed a vellum copy and was traveling to Washington to present it to the chief executive.

If the youth did not have a future in biography, he certainly had one in advertising. He said he had a copy of his book for ex-President Coolidge, too, and planned to present it personally. Marsh knew enough about advertising to know that it did not come free. In order to raise money to publicize his biography, he proposed a scheme to the Herald Tribune. "Now to do a quick business we need cash, now I would like to ask a favor of you, do you have any friends who would like to have a couple of boys do some advertising for them, we can do anything from cleaning teeth with Listerine tooth Paste to trying on shoes and clothes." As advertisers, the boys were quite versatile. "My brother has a Columbia bicycle. If the Columbia people would pay us, we will have our pictures taken and then will say down at the bottom ('Ride with us to success on a Columbia.')"

He explained that he and his brother could sit in a store window of a bookshop and demonstrate how they printed their book. "If we can we would like to have our dog sit in the window with us. She is very kind and a peach when it comes to hunting." Billy concluded his suggestions for promoting Our President Herbert Hooverwith a bit of flattery. "If I come to New York can I see you? I think I have heard people say Editors don't have time to bother with people, but you might be a little different from some of them."

After Herald Tribune headlines appeared on June 29, 1930, Billy rose early to read his mail while photographers and newsreel-grinders gathered outside his home. He talked to reporters for more than an hour, then he greeted residents of New Milford who dropped by to congratulate him. Billy made plans to travel to New York to thank the Herald Tribune.

Learning of the book, the manager of the Doubleday, Doran Company tracked the head of the editorial department to his golf club and planned to beat the competition by signing a contract. At this point the manager had not even read the book, only newspaper excerpts. He stopped at the Herald Tribune office to borrow a copy, which he scanned as he sped toward New Milford. When he reached New Milford it was late, and Billy had gone to bed. His parents awakened him, and he signed the contract while still in his pajamas. The publisher's version was an exact facsimile, with the addition of a title page and a postscript to the original preface. Four other publishers arrived too late. Later it was learned Marsh himself had tipped off Doubleday. This opportunistic boy did not need a literary agent. Doubleday revved up its presses and rushed out a mass edition on July 11, 1930, the same day the Marsh boys met the President.

Hoover met Billy and Charles on the White House lawn, and they were photographed, flanking the President, with Charles holding a copy of the famous book. Asked if he was intimidated to meet the President, Billy replied, "Not so scared."

"You are starting a publishing house very young, are you not?" the President asked.

"Yes, Mr. President," Billy replied.

Hoover seemed quite pleased with his young friends. No so well known to the public is that Hoover loved the company of all children. All three smiled happily. The President accepted his specially printed copy and examined it. Billy had inscribed it "To our President, Herbert Hoover, from the author, William J. Marsh, Jr., New Milford, Conn., July 10, 1930, age 11 years."

Billy also gave him a guidebook of New Milford and another copy of the book for the First Lady. This had been Charles's idea. Then they shook hands and the "conference" ended. But as they were preparing to leave the grounds, George Akerson, the President's secretary, led them back and gave a tour of the Oval Office and the Cabinet Room. He then turned the pair over to Chief Usher Ike Hoover, who led them through the remainder of the White House, including the Blue Room and the East Room. As they prepared to go to the second floor of the White House, another usher informed the boys that the President wanted to see them again. With him was First Lady Lou Henry, who had left her luncheon to meet them. She thanked Charles for the copy he had brought for her.

Afterward, the entire Marsh family, escorted by their publisher's representative, saw as much of Washington as they could in a day. Billy's priorities were the Smithsonian, Lindbergh's plane, and the first automobile. When his mother asked if he would like to see the Senate in action, he said he would rather not. They did see the major monuments. Billy said the White House was not quite what he expected. "There weren't any statues of Lincoln and George Washington—I thought there would be statues there."

Speeding north to New York after their visit with the President, the boys spent four hours the following day autographing books in the windows of the Stern Brother's Book Store. Nearby, they ran off souvenir photographs for patrons on their old printing press. The New York World lauded their tiny tome, which sold for $1.00, as a "masterpiece of naïve biography."

Asked his impressions of the President, Billy replied, "He is just as nice as I said he was in my book."

The boys described Lou Henry Hoover in glowing terms. "She is very pretty and she wears the new style dresses, quite long," Billy said.

The day after their book signing in New York, the brothers delivered a radio address. Charles described himself as "half-owner and helper of Marsh's printing business." Then Billy, the senior partner, took over. He read a six-page address he had written describing his ascent to fame, peaking with his visit with the President. By this time the glow of fame was waning from exhilaration to exhaustion. In a two-room suite of the Hotel Roosevelt, where they and their parents were guests of the management, the tired young writers fended off questions. They seemed eager to go back to being boys.

At least one major daily (the clipping is unmarked) reviewed the book in detail, quite favorably. In fact, during the whole affair, no one publicly criticized the book for being too complimentary to the unpopular President. The review concluded: "Fine book! Behind it is clear enterprise—good stuff for any boy or girl to have. Pushing it is not only good for industry, but a real host of feeling toward the good things of life, and with it, a courage of expression that a little later would, more than likely, have been less outcoming, more self-conscious. Here is the hour just before William J. Marsh grows painfully aware of himself."

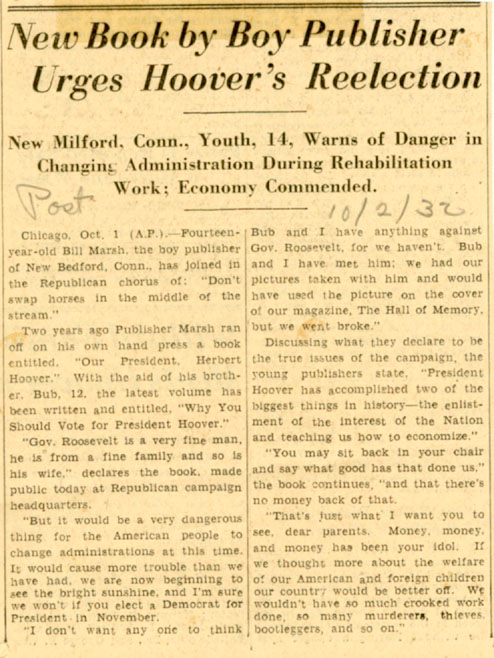

The story might end here. Billy Marsh might have faded quickly into obscurity. But no, in 1932, at 14, with the presidential election imminent, Billy published a second book. Hoover was still his hero, and Billy urged voters to reelect him. Marsh had nothing against FDR, whom he said came from a fine family, as did Eleanor. But it would be perilous to change directions when Hoover had the Depression on the run. "It would cause more trouble than we have had, we are now beginning to see the bright sunshine and I'm sure we won't if you elect a Democrat for President in November." Hoover, he said, had enlisted the people of the nation and taught them to economize.

You may sit back in your chair and say what good has that done us, and that there's no money back of that. That's just what I want you to see, dear parents. Money, money and money has been your idol. If we thought more about the welfare of our American and foreign children our country would be better off. We wouldn't have so much crooked work done, so many murderers, thieves, bootleggers, and so on.

The second book did not attract as much attention as the first. Perhaps the novelty had worn off. Perhaps the Depression was too deep, the mood of the country too sour. But for one young boy approaching adolescence, America was still a great place, and Herbert Hoover was still a great man.

Glen Jeansonne, professor of history at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee since 1978, has taught at the University of Louisiana-Lafayette, Williams College, and the University of Michigan. He is the author or editor of nine books, including A Time of Paradox: America Since 1890; Women of the Far Right; Messiah of the Masses: Huey P. Long and the Great Depression; and Gerald L. K. Smith: Minister of Hate. The latter was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in biography. He is currently working on the first single-volume biography of Hoover based on primary sources in a generation.

Note on Sources

The Herbert Hoover Presidential Library in West Branch, Iowa, holds two copies of the book Our President: Herbert Hoover, by William J. Marsh, Jr. (New York: Doubleday, Doran, 1930). One copy has its original light blue dust jacket with photographs and promotional text. The book was briefly a publishing sensation and produced front-page headlines in several dailies for a short time, which included coverage of the boys' visit to the White House at the invitation of Hoover.

The most useful articles appear in the New York Herald Tribune, which ran feature stories on June 30, July 7, 11, and 12, 1930; the Washington Herald, June 29, 1930; the New York Evening Post,July 10, 1930; the New York World, July 11, 1930; and the New York Times, July 13, 1930. There is a rather detailed review in an unmarked clipping of July 29, 1930.

The only story about Marsh's second book appears in the New York Evening Post, October 2, 1932. All of the clippings were found in the newspaper clipping file of the Hoover Library. The boxes are arranged by date with no box numbers. Newspapers are interfiled rather than segregated. I discovered the stories while routinely combing the years of Hoover's presidency. I then asked if the library had a copy of the book itself, which we located. We found no trace of the second book, nor a subsequent mention of Marsh.