VIPs in Uniform

A Look at the Military Files of the Famous and Famous-To-Be

Spring 2006, Vol. 38, No. 1

By Ellen Fried

What do George Patton and Elvis Presley, John F. Kennedy and Jack Kerouac, Jimi Hendrix and Jackie Robinson all have in common—besides being famous?

They all served in the military. And, as of last year, their military files are all open to the public.

For decades, the National Archives and Records Administration's National Personnel Records Center (NPRC), in St. Louis, Missouri, has stored and serviced the military's personnel records—specifically, the Official Military Personnel Files, or OMPFs. Now numbering about 56 million, these files date back to the mid to late 1800s, when the system of keeping individual military records began.

Until recently, even the oldest OMPFs remained the property of the military service branches. Access to the files was limited mostly to the former service members themselves and, after they were deceased, to their next of kin, who used the material primarily to verify their eligibility for benefits.

But the files contain a vast amount of historical information that could be of value to historians, biographers, genealogists, and other researchers. In the late 1990s, NARA and the Department of Defense agreed in principle that the OMPFs were permanently valuable historical records that should be transferred to NARA's custody and made available to the public. Over the next few years, the two agencies worked out a schedule by which the records would be transferred. And in July 2005, NARA opened the first batch—about 1.2 million OMPFs for Navy and Marine Corps enlisted personnel who served between 1885 and 1939.

For the most part, a service member's file is eligible to be transferred to NARA when at least 62 years have passed since the member separated from service. But there are exceptions: the files of VIPs, or, more precisely, PEPs—Persons of Exceptional Prominence.

NARA has identified OMPFs for about 3,000 PEPs—people who, because of their exceptional prominence, can be expected to be of exceptional interest to researchers. The list includes military leaders, Medal of Honor recipients, Presidents, athletes, actors, authors, musicians, even famous criminals. "It's the good, the bad, and the ugly of society," jokes Bryan McGraw, director of the NPRC's archival programs. These files are eligible to be opened to the public 10 years after the celebrity's death.

And so, along with the 1.2 million files of the rank and file, NARA released the first 150 files of PEPs, including the likes of Spiro Agnew and Arthur Ashe, Humphrey Bogart and Frank Capra, Henry Fonda and Alex Haley, Lyndon Johnson and Charles Lindbergh.

What's in these files? Lots of things: enlistment records, medical reports, biographical questionnaires, training records, performance reviews, award citations, records of disciplinary action. "But each record is unique," points out William Seibert, chief of the NPRC's archival operations, "as is each individual."

In a collection of military files of famous people, you'd expect to find files of people who are famous specifically because of their military service. Some of the big names of American military history are represented here—such as Douglas MacArthur and George S. Patton, Jr.

When it comes to individuals who spent their entire careers in the military, the OMPFs can be huge. The files paint detailed pictures of the subjects' adult lives, documenting exactly where they went and what they did each year. These files represent a gold mine for biographers.

MacArthur's career spanned almost 50 years, during which time he took part in three major wars and became the most decorated soldier in the history of the U.S. military. He ultimately rose to the rank of General of the Army, one of only a handful of people ever to hold that rank. MacArthur's OMPF is one of the largest in existence, encompassing more than three cubic feet. It extends from his June 1903 graduation from the U.S. Military Academy (standing no. 1 in a class of 93 members) and assignment as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to the April 1951 telegram by which, following a disagreement over whether to attack China, President Harry S. Truman effectively ended the multi-titled general's military career:

DEEPLY REGRET THAT IT BECOMES MY DUTY AS PRESIDENT AND COMMANDER IN CHIEF OF THE UNITED STATES MILITARY FORCES TO REPLACE YOU AS SUPREME COM MANDER CMA ALLIED POWERS SEMICOLON COMMANDER IN CHIEF CMA UNITED NATIONS COMMAND SEMICOLON COMMANDER IN CHIEF CMA FAR EAST SEMICOLON AND COMMANDING GENERAL CMA UNCLE SUGAR ARMY CMA FAR EAST PD PARA YOU WILL TURN OVER YOUR COMMANDS CMA EFFECTIVE AT ONCE

Along the way, efficiency reports and citations laud MacArthur as "an able, capable, reliable, and self-reliant officer," "a particularly intelligent and efficient officer," "an exceptionally excellent officer in every respect," and "a brilliant commander of skill and judgment." But, in keeping with the adage that a picture is worth a thousand words, a photograph in the file speaks perhaps most compellingly about MacArthur's character. Taken in France in August 1918, it shows the young brigadier general—the youngest one ever in the Army—standing on the steps of a military headquarters building, cigar in one hand and riding crop in the other. How the photograph got into the file is unknown, but its message is unmistakable: Here is a man in charge of his destiny, a force to be reckoned with.

Not quite as large as MacArthur's file, but still impressive, is the file of George S. Patton, which documents a 36-year military career in about a cubic foot of space. An efficiency report from September 1919 describes the then-33-year-old colonel as "Possessing great dash and courage." The comment provides insight not only into Patton's nature but also into the nature of the Army and even of language in the early 20th century—who today would use the word "dash" in a soldier's performance review? But, while evocative of Patton's charisma, the 1919 comment gives no hint of the volatility that would later get him into trouble—such as when, in 1943, he slapped two hospitalized privates and accused them of cowardice. A remark in a 1944 efficiency report sums up both Patton's military talent and his rough edges: "A brilliant fighter and leader. Impulsive and quick tempered. Likely to speak in public in an ill-considered fashion." The report is signed by Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower.

While some of the PEP files belong to people who are famous because of their achievements in the military, others belong to people who were famous before going into the military. Their fame could be either a hindrance or a help to the armed services.

In the days before the all-volunteer military, celebrities were drafted just like other young men. One such celebrity was Elvis Presley, who was inducted into the Army in March 1958, at the height of his fame. His induction created a public relations headache. Bereft fans wrote to the President, the draft board, and anyone else who they thought could bring their idol back home. The following letter to First Lady Mamie Eisenhower was forwarded to the Army ("Respectfully referred for appropriate handling," states a note from the President's assistant) and ended up in Presley's OMPF:

But while some citizens wanted Presley out of the Army, others wanted to make sure he stayed in; it seemed the Army couldn't win either way. When a gossip columnist reported in July 1959 that Presley might receive an early discharge for "good behavior," indignant letters poured in to Congress and were forwarded to the Army. "What is this 'good behavior' thing in the Army?" demanded a William J. F. Clark, from Brooklyn. "I have the impression that such premature release for 'good behavior' applied only to felons in prison. . . . My son . . . was inducted prior to Mr. Presley, arrived in Germany prior to Mr. Presley—and has not been offered any such early discharge."

Dear Mamie,

Will you please please be so sweet and kind as to ask Ike to please bring Elvis Presley back to us from the Army. We need him in our entertainment world to make us all laugh. The theatres need him to help fill their many empty seats. . . . Also did you know Elvis has been paying $500,000 in income taxes. We feel the huge taxes he has been paying could help our defense effort far more than his stay in the Army. Please ask Ike to bring Elvis back to us soon.

The Army seems to have had its hands full answering all the inquiries. "Good behavior is expected of all men in the Army," state the replies. "Elvis Presley will not be released in a manner different from any other inductee serving overseas."A May 1959 memorandum from the assistant deputy chief of staff for personnel puts a positive spin on Presley's presence in the military, suggesting that the Army's impartial treatment and Presley's dutiful service would help to inspire other young men: "Many teenagers who look up to and emulate Private First Class Presley will, to a varied degree, follow his example in the performance of their military service." Still, perusing the OMPF, one can't help but imagine that the Army breathed a collective sigh of relief when Presley returned to civilian life in March 1960.

Like Presley, Joe Louis Barrow—better known as Joe Louis—was at the height of his fame when he was drafted into military service. When he received his induction order in January 1942, he had been the heavyweight champion of the world for almost five years. Louis's fame, however—unlike Presley's—seems to have been an unqualified benefit to the Army.

Louis served with the Special Services Division and was assigned to an "entertainment and interracial relations morale mission." He toured through Army camps in the United States, Europe, and North Africa, entertaining a total of about two million soldiers with boxing exhibitions. Louis's OMPF brims with praise for his generosity and courage and for his "incalculable contribution to the general morale sustaining program within the Army."

In an October 1944 memorandum, Capt. Fred Maly, officer-in-charge of the Joe Louis Tour, recommends Louis for the Legion of Merit. Maly observes that Louis boxed so frequently for the troops that he suffered fist injuries that endangered his boxing future, "yet he risked all willingly rather than disappoint soldiers who frantically stormed by thousands to the scene of his exhibitions." Maly also notes that Louis visited hospitals to give comfort to the sick and wounded and describes how "dying soldiers were given an extra 'lift' from a personal chat with Louis." In summary, Maly declares that Louis deserves the decoration "because his unusual devotion to duty, interest, initiative, willingness, efforts, and frequent disregard of jeopardizing his valuable boxing career were far beyond that which was reasonably expected or demanded of him." Louis was awarded the Legion of Merit two weeks later.

Some of the most intriguing OMPFs are for People of Exceptional Prominence who did not become prominent until after they left the military. Their files are often prophetic, providing glimpses of the talents, traits, and tendencies that would mark their post-military life.

In April 1947, at the tender age of 17, Steve McQueen—full name Terrance Steven McQueen—enlisted in the Marines. His military file reveals that, in 1949, he spent 30 days in the brig and was fined $90 for being AWOL for several days from his camp in North Carolina. In his statement about the incident, he declares, "I did not register for the selective service," suggesting he may have thought that since he had joined the military voluntarily, he should be free to come and go as he pleased.

After being honorably discharged from the Marines in 1950, McQueen worked at a variety of jobs before finally enrolling in acting school. He would become famous for such movies as The Great Escape and Papillon, playing rebellious prisoners with a profound desire for freedom.

In December 1942, a year after walking away from a football scholarship at Columbia University, Jack Kerouac enlisted in the Navy. He was 20 years old. His love of writing, resistance to regimentation, spiritual questing, and inner demons all can be seen in his military file.

After only eight days on active duty, Kerouac was admitted to the sick list, complaining of headaches. He was diagnosed with "dementia praecox"—an antiquated term for schizophrenia—and ended up spending weeks in naval hospitals, being questioned by numerous psychiatrists who produced pages and pages of medical history.

A number of passages attest to Kerouac's literary calling. "Patient states he believes he might have been nervous when in boot camp because he had been working too hard just prior to induction," notes one entry. "He had been writing a novel, in the style of James Joyce, about his own home town, and averaging approximately 16 hours daily in an effort to get it down." Another entry reveals as much about the doctor's attitude toward literature as about Kerouac's: "Without any particular training or background, this patient, just prior to his enlistment, enthusiastically embarked upon the writing of novels. He sees nothing unusual in this activity."

Other entries paint a picture of a restless soul straining against restriction. "Patient believes he quit football for same reason he couldn't get along in Navy, he can't stand regulations, etc.," observes one doctor. Another apparently consulted Kerouac's parents and recorded the following: "Leo A. Kerouac states that his son has been 'boiling' for a long time. Has always been seclusive, stubborn, headstrong, resentful of authority and advice."

Brought up Catholic, Kerouac had "marked conflicts about his religion," according to a remark on page 9 of the medical history. "He is trying to resolve, according to his parents, a religious philosophy that will be satisfactory to himself. Also he tends to brood a good deal." And another entry, under the heading of "Habits," notes concisely, "Spree drinker."

Kerouac was discharged from military service in June 1943 for reasons of "unsuitability." He would go on to publish several novels, pioneering an unfettered, stream-of-consciousness style that he dubbed "spontaneous prose." In Buddhism, he would find the more satisfactory religious philosophy he had sought, and he would chronicle his spiritual explorations in his book The Dharma Bums. Ultimately, he would sink into alcoholism, which would kill him at the age of 47.

James Marshall "Jimi" Hendrix is another artist whose dedication to his art—and resistance to authority—show up clearly in his military file.

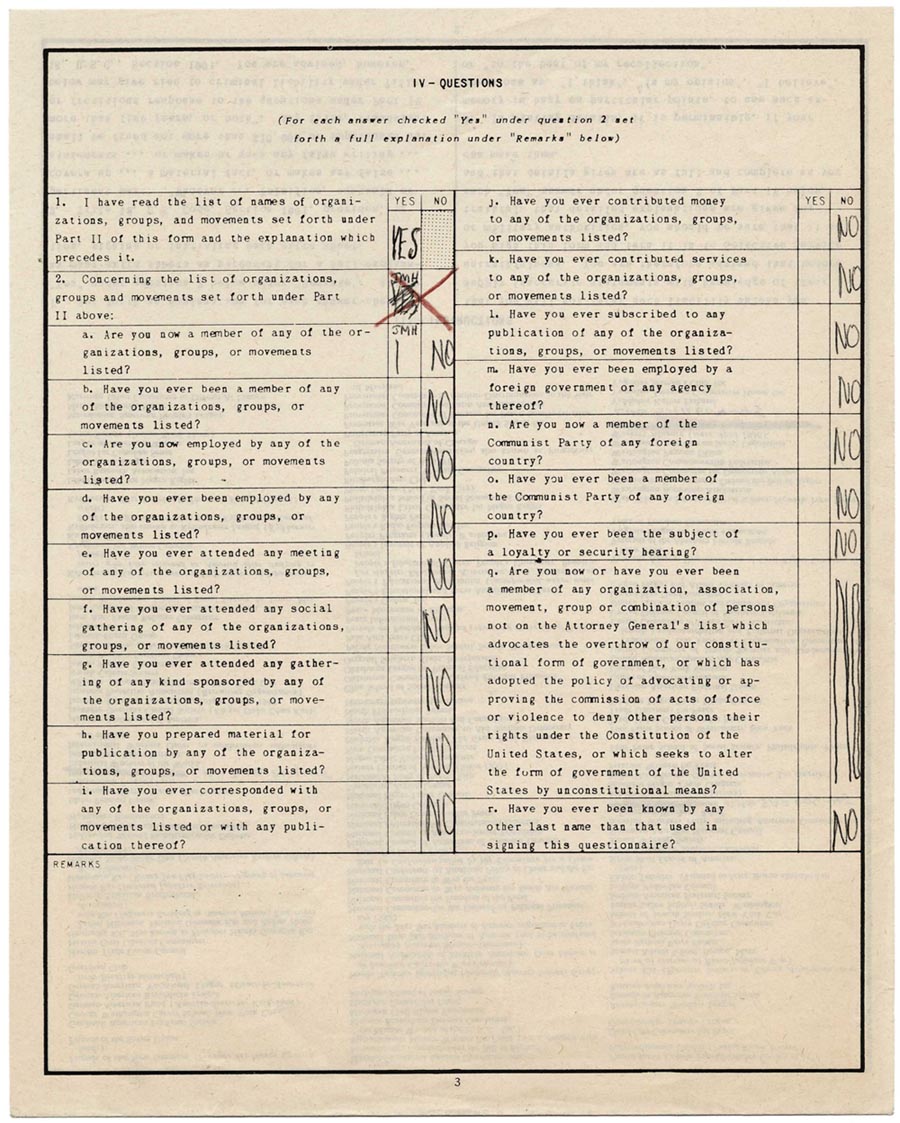

Hendrix enlisted in the Army in May 1961, at the age of 18. Under the heading "Avocations and Sports," his Enlisted Qualification Record states, "Plays Guitar (3 yrs)." Both creativity and nonconformity are revealed by other enlistment documents, such as a security questionnaire on which Hendrix takes a novel approach to filling in check boxes.

Hendrix's interest in guitar seems to have taken precedence over any commitment to military service. "Pvt Hendrix plays a musical instrument during his off duty hours, or so he says," declares one Sgt. Louis Hoekstra. "This is one of his faults, because his mind apparently cannot function while performing duties and thinking about his guitar." A training record from July 1961 shows Hendrix at the bottom of the heap in marksmanship—ranked 36th out of a group of 36. While he may have been right on the mark with a guitar, with a rifle he was not even close.

In a request that Hendrix be subjected to physical and psychiatric examination, a Capt. Gilbert Batchman asserts, "Individual is unable to conform to military rules and regulations. Misses bed check; sleeps while supposed to be working; unsatisfactory duty performance. Requires excessive supervision at all times." A May 1962 document recommending that Hendrix be discharged from service states tersely, "No known good characteristics."

Within a few years, Hendrix would be hailed as one of the most influential electric guitarists of all time.

In a way, celebrities are no different from ordinary service personnel; their military files reveal both talent and trouble, fearlessness and foibles. "They're just humans," says archival director McGraw. He points out that while the files of VIPs have grabbed the spotlight, the vast majority of the OMPFs relate to unsung heroes. "You look at the rank and file, you look at the things they did. . . . While they're not celebrities, they're equally important." So, while biographers and historians peruse the celebrity files, family historians and genealogists will look for treasures in the files of other soldiers.

More OMPFs for Persons of Exceptional Prominence will be released in the future, as the files are processed by the National Personnel Records Center and as the 10-year mark from more celebrity deaths is reached. Among the files expected to be released next are those of Medgar Evers, Adlai Stevenson, Spencer Tracy, Jerry Garcia, and Jeffrey Dahmer. What revelations will these files hold about the experiences and personalities of the people whose service they document? The answers will be available to any researcher.

Articles published in Prologue do not necessarily represent the views of NARA or of any other agency of the United States Government.