The Presidential Libraries Act after 50 Years

Until Franklin D. Roosevelt opened the first presidential library in 1941 and transferred it to the federal government, there were no official repositories designed especially to preserve and make accessible the records of Presidents. It was 16 years before another presidential library opened—this time under the provisions of the Presidential Libraries Act of 1955.

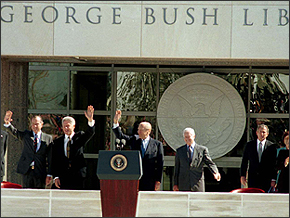

Since 1941, 10 more presidential libraries have opened around the country, with two more scheduled. One will be for President George W. Bush, and the other will result from the conversion of the private Nixon Library in Yorba Linda, California, into a federal facility that includes records of Richard M. Nixon's presidency, now with the Nixon Presidential Materials Staff at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

These libraries, all built with nonfederal funds then donated to the federal government, are operated and maintained by the National Archives and Records Administration and staffed by NARA employees who care for the archival records and the museum collections and make them available for research. Although the libraries are federal facilities, they also draw support from affiliated foundations or institutes that help underwrite research grants, outreach programs, exhibits, and other program and facility enhancements.

In this special "Spotlight on NARA," Raymond Geselbracht and Timothy Walch trace the origins of the important 1955 legislation.

The Presidential Libraries Act after 50 Years

By Raymond Geselbracht and Timothy Walch

Last November 18, former President William J. Clinton exercised the provisions of a little-known law that has helped assure the preservation of presidential history for 50 years.

On that day, he transferred ownership of the new William J. Clinton Presidential Library to the U.S. Government, marking the 10th time since 1955 that a former President had invoked the Presidential Libraries Act.

Signed into law on August 12, 1955, the act provides for the orderly transfer of presidential papers and memorabilia to the federal government. The law also permits former Presidents to build "presidential libraries" at no expense to the government and to transfer these facilities to the government along with their personal property. The government, in turn, agrees to maintain both the property and the buildings at public expense.

The origins of the act—and the current system of presidential libraries within the National Archives and Records Administration—stem from the uncertain status of presidential records after a President left office. Until the passage of the act, it had been customary for Presidents to take these records with them as their personal property. The records were often passed from one generation to the next with little concern for their value to the history of the nation. Some presidential collections were well preserved by their heirs, but others were broken up and dispersed, or were partially destroyed.

In an effort to preserve presidential history throughout the 19th century, the federal government purchased collections of presidential papers on several occasions. In 1903, the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress took on the responsibility of preserving these records and sought to acquire additional presidential collections but met with mixed results. Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the widow of Woodrow Wilson complied, but Herbert Hoover and the widows of Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge made other plans.

Although Franklin D. Roosevelt had considered depositing his papers in the Library of Congress, he eventually chose a different path, one that led directly to the 1955 legislation. In December 1938, Roosevelt announced plans to build a "presidential museum" on the grounds of his family estate in Hyde Park, New York. The President would donate the land and his papers and memorabilia to the government, and the museum would be constructed with private funds. The President also specified that the National Archives, which had been established just a few years before, would administer the new facility. Since he wanted a title for the new institution that every American could understand, he called it "the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library." When the building was completed in 1941, it was accepted by a joint resolution of Congress. No thought was given at the time to the precedent he had set by building and donating this "presidential library" to the federal government.

When Harry S. Truman became President upon Roosevelt's death on April 12, 1945, he faced the immense responsibilities of ending World War II and bringing a stable peace to a shattered world. He gave little thought about what to do with his presidential materials until early in 1950.

Sometime that spring, he asked one of his staff assistants, George Elsey, to work with the Archivist of the United States, Wayne Grover, to make arrangements for the transfer of his presidential materials to the government. In June, he asked an architect to design the "Truman Library." In July, he allowed some of his close friends to establish a formal group called The Harry S. Truman Library, Inc., to raise money and build the facility.

Elsey and Grover drafted legislation allowing the government to accept deposits of presidential papers. This legislation, called the Federal Records Act, was passed by the Congress in August 1950. Almost as soon as it was signed into law, however, the law proved unsuitable for Truman's donation. One problem was that the law did not provide firm protection for the Truman papers from unauthorized access by a successor President or by the Congress. A second shortcoming was that the law didn't include a provision that would allow the government to accept land and a library building.

By the fall of 1951, Truman and his advisers understood that new legislation would be needed. Unfortunately, several problems and unresolved issues slowed the process. Among them was concern that legislation for a Truman Library would stir up congressional attacks on the costs of operating the Roosevelt Library. And there was controversy over a fundraising letter for the library that offered a tax deduction, at a time when taxes were high and the country was at war in Korea, and that seemed to offer special influence with the President. Bad publicity forced Truman to end the fundraising effort for the time being.

Legislation that would allow the government to accept a Truman Library was drafted in 1952, but it was never sent to Congress. When Truman left office in January 1953, the government still did not have the legal authority to accept a presidential library.

A few days before he left office, Truman sent a letter to the Administrator of General Services stating his intention to give his presidential materials to the government. He also requested "two or three archivists" to organize and describe his papers during the time prior to their transfer to the government, which would occur, Truman hoped, as soon as the needed legislation was passed.

Truman took his presidential materials with him to Kansas City, Missouri, after his presidency. Although he maintained physical control, his materials in fact rested in a legal limbo. They were personal property that had been promised to the government, and it was understood that Truman would not sell or destroy any of it. It was, temporarily, private property held in the public interest, awaiting the passage of legislation that would resolve this conflicted status.

Planning for the library went forward in the months following Truman's return to private life. By late 1954, it was clear that a Truman Library could be funded and built, if the government would accept it. In January 1955, David Lloyd, a Truman aide who had taken the project from Elsey, sent Grover a draft resolution that would authorize the government's acceptance of the Truman Library.

Grover revised Lloyd's draft to allow the government to accept libraries from any President, past or future. He also inserted language that allowed states, universities, foundations and institutes to become partners with the government in establishing presidential libraries.

Grover and Lloyd also were careful to keep the White House and the Eisenhower Foundation (a nonprofit group formed in 1945 to honor Eisenhower's legacy) informed of their efforts. They also shared drafts with Arthur Minnich, an assistant to President Eisenhower who passed the information on to library supporters. As early as February 1954, Minnich wrote to House Speaker Joseph Martin to determine if there was any pending legislation on presidential papers. Minnich told Martin that Eisenhower would be receptive to an act to codify presidential libraries and would issue a preliminary statement on the disposition of his papers if that was advisable.

The House held hearings on the Presidential Libraries Act on June 13, 1955. Grover was the primary witness speaking in support of the act. No one testified in opposition, and the legislation passed without controversy. It was signed by President Eisenhower on August 12.

There is no evidence that any of the Presidents immediately affected by the new law—Hoover, Truman, or Eisenhower—took a significant role in drafting or promoting the Presidential Libraries Act. They had, as they had done so often during their presidencies, trusted others to do the good work necessary to bring about a desired end that they and their advisers had identified.

A groundbreaking ceremony for the Harry S. Truman Library was held on Truman's birthday, May 8, 1955, and the library was dedicated on July 6, 1957. At the dedication ceremonies, according to the provisions of the Presidential Libraries Act, President Truman formally gave his presidential materials to the Archivist of the United States, and The Harry S. Truman Library, Inc., presented the library land and building to the Administrator of General Services. This was the first time that a former President invoked the provisions of this new law.

Eisenhower had signed the legislation with little ceremony, but it was clear that he intended to build a "library" on the grounds of a preexisting center in his home town of Abilene, Kansas. In 1954, for example, the Eisenhower Foundation opened a museum to recognize Eisenhower's role in world history and began to raise money for a library that would be dedicated in April 1962.

Former President Herbert Hoover was interested in the new law because it meant that his papers would be eligible for funding at some future date. At the time of the passage of the act, Hoover still assumed that his personal papers would remain at the Hoover Institution on the campus of Stanford University, his alma mater.

But Hoover's relationship with Stanford became troubled in the late 1950s. In 1958, he allowed friends to begin fundraising for a small museum in his hometown of West Branch, Iowa. As his conflict with Stanford worsened, Hoover decided to donate his personal and presidential papers to the National Archives and expand the West Branch facility, but he left his records of his numerous relief efforts at the Institution. The Hoover Presidential Library-Museum was donated to the federal government on the President's 88th birthday, August 10, 1962.

The Presidential Libraries Act has been used 10 times to bring presidential libraries into the government. But the act was not perfect, and elements of the law have been revised several times since 1955. Most notably, in 1986 Congress required that subsequent presidential libraries include an endowment, whose amount would be linked to the size of the library, to help the National Archives cover the costs of maintenance and upkeep.

Unfortunately, the act was only partly successful at resolving the ownership of presidential papers. The federal government hoped that the new law would breach the divide between official and personal equities in presidential papers. Presidential materials would remain personal property, but former Presidents would never destroy or otherwise dispose of any materials. Instead, they would give their materials to the government, along with a facility to hold them; the government in turn would take care of the materials forever and make them available for research.

The compromise had a serious flaw, however, which was that the Presidential Libraries Act did not require that a President donate his official papers to the National Archives, and therefore did nothing to prevent a former President from asserting personal property rights in presidential materials, such as by destroying or not donating some or all of the materials. A determined President could thus dispose of presidential materials in a way that the American people would not tolerate, as Richard Nixon attempted to do shortly after he resigned the presidency in 1974. Congress and President Gerald R. Ford prevented Nixon from destroying some of his presidential materials—most importantly, the White House tape recordings—by enacting the Presidential Recordings and Materials Preservation Act of 1974.

In response, President Jimmy Carter signed into law the Presidential Records Act of 1978. This act declared that, starting with the next presidential administration, the official papers of the presidency would automatically become government property, would be transferred to the National Archives at the end of the administration, and would be subject to public request and disclosure five years after the end of the administration. A President would still have to utilize the Presidential Libraries Act if he wanted to build or donate a library to house the presidential records, which all Presidents have continued to do.

The 1978 act, however, requires that the National Archives follow special procedures to allow both the former and incumbent Presidents to review the records before they are released to the public. These procedures, which were revised in 2001 under Executive Order 13233, ensure that the former President has a full opportunity, as required by the Supreme Court, to assert possible claims of executive privilege.

Although less than perfect, the Presidential Libraries Act of 1955 has been a valuable law that has substantially ensured the preservation of the documentary legacy of the American presidency. In addition, the presidential libraries have proved to be very effective providers of access to presidential materials, and their museum exhibits and public and educational programs have benefits for millions of people.

The 1955 law has fulfilled the vision expressed by Franklin D. Roosevelt when he stated that his library and all future presidential libraries are "proof—if any proof is needed—that our confidence in the future of democracy has not diminished and will not diminish."

Note on Sources

This article was based on research in the papers of Presidents Hoover, Truman, and Eisenhower. The authors wish to acknowledge the research assistance of Spencer Howard at the Hoover Library and Martin M. Teasley at the Eisenhower Library. For more information about the history of presidential papers and libraries, the authors recommend Raymond Geselbracht, "The Four Eras in the History of Presidential Papers," Prologue: Journal of the National Archives (Spring 1983): 37–42; H. G. Jones, The Records of a Nation (New York, 1969): 144–171; and Donald R. McCoy, The National Archives: America's Ministry of Documents, 1934–1968 (Chapel Hill, NC, 1978): 291–308. Also of some value is Frank Schick, et al., Records of the Presidency: Presidential Papers and Libraries from Washington to Reagan (Phoenix, AZ, 1989).

Raymond Geselbracht is special assistant to the director of the Harry S. Truman Library in Independence, Missouri. He is a frequent contributor to Prologue, including articles on Truman's relationship with the Marx Brothers, his love of poker, and his schooling in Independence, Missouri.

Timothy Walch is director of the Herbert Hoover Library in West Branch, Iowa. A former editor of Prologue, he is the author of many books, including Uncommon Americans: The Lives and Legacies of Herbert and Lou Henry Hoover (2003).

Learn More about Presidential Libraries