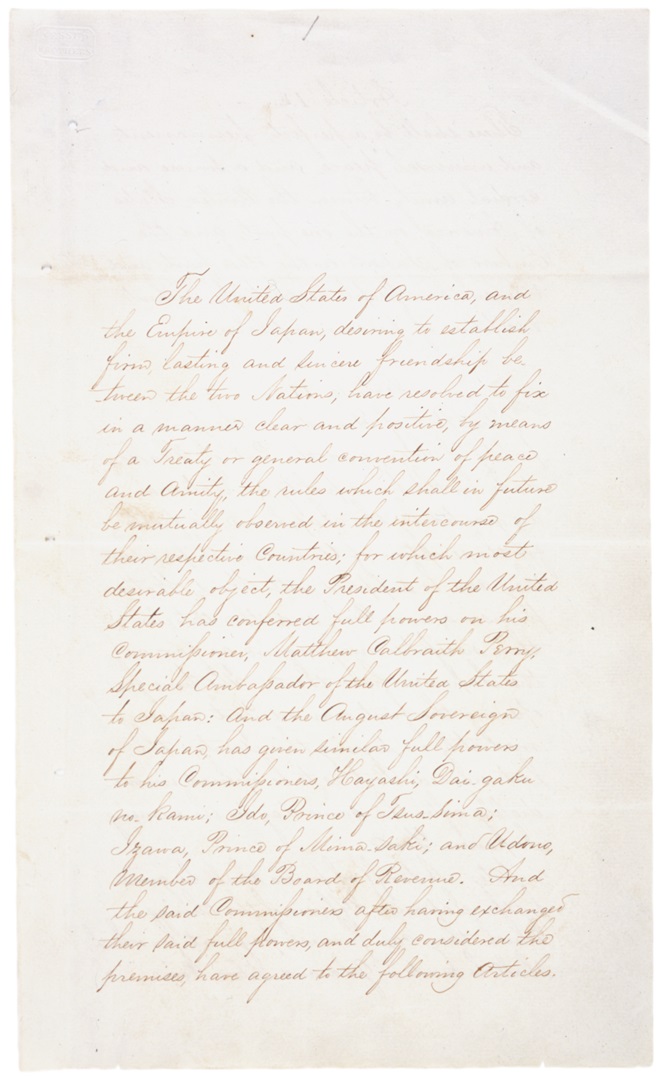

Treaty of Kanagawa

Spring 2004, Vol. 36, No. 1 | Pieces of History

By the mid-1800s, the United States had achieved Thomas Jefferson’s dream of a nation stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

Now, America was seeking to extend its power and influence, if not its borders, to the Far East. Already, it was trading with China, but now it was focusing on Japan, a closed society whose rulers went to great lengths to keep the outside world out.

The Tokugawa Shōgunate, which had ruled Japan since the sixteenth century, decreed in the 1600s that all commerce with the West would be carried out through an island in the port of what is now Nagasaki and only through the Dutch—keeping foreigners away from the mainland.

But in 1853, the outside world came knocking, even kicking, on Japan’s closed door. Commodore Matthew Perry arrived from the United States to obtain a treaty that would open Japan to commercial interests and establish it as a stopover for trade with China.

Perry sailed into what is now Tokyo Bay in July 1853 with a sinister-looking armada of four “black ships,” described as such by the Japanese because of their color and the smoke that spewed from their stacks.

He insisted on seeing high-ranking officials, but the Japanese refused. He then delivered a letter from the President requesting a treaty and vowed to return the next year for a response.

Before he left, however, he moved his “black ships” closer to Tokyo as a show of force.

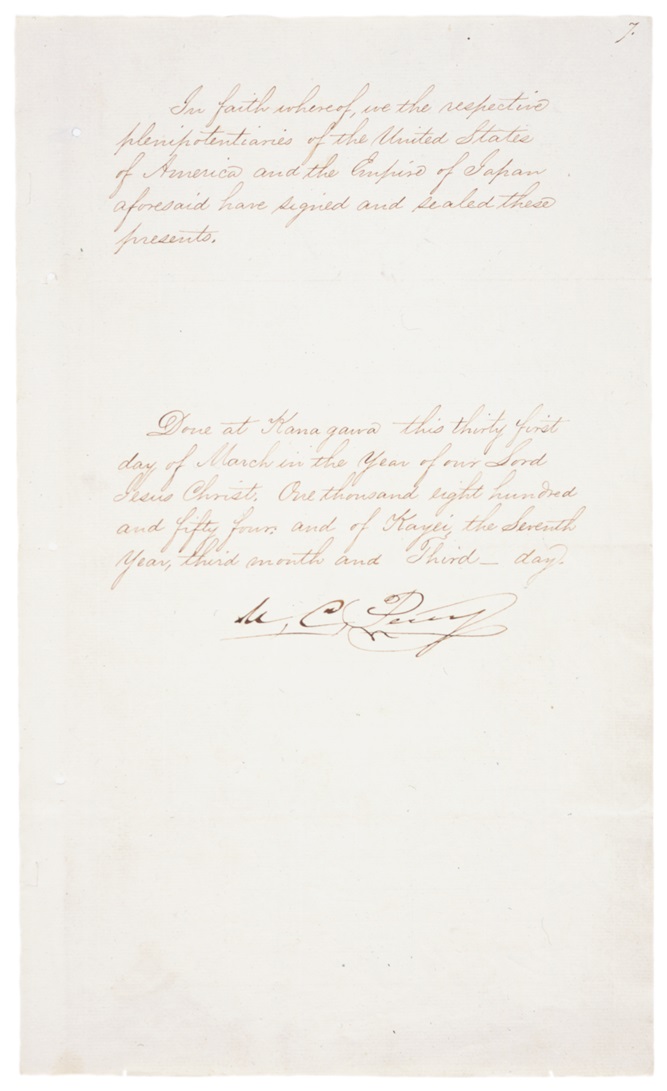

In March 1854, Perry returned, this time with nine ships, sailing farther into Tokyo Bay than he had the year before. The nervous Japanese finally talked him into moving to Kanagawa, a port forty-five miles away.

With the nine ships staring at them, the Japanese finally agreed to a treaty. It included a promise of “perfect, permanent, and universal peace” between the two countries; opening two ports to shipwrecked U.S. sailors and ships in need of supplies; and Japan’s consent to a U.S. consul in Japan.

The treaty contained no trade provision—that would come later—but it marked the opening up of a closed society and the beginning of a 150-year relationship with the Americans.

Walter La Feber, writing in The Clash: U.S. Japanese Relations Throughout History, sums up the significance of the Treaty of Kanagawa: “After two centuries of dealing only with the Dutch, the 250-year-old Tokugawa Shōgunate opened itself—carefully, narrowly, and fearfully—to the recently born United States.”