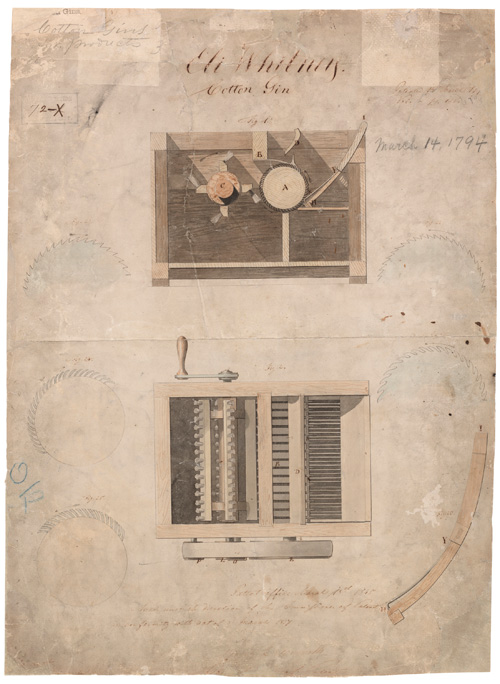

Eli Whitney’s Patent for the Cotton Gin

Fall 2004, Vol. 36, No. 3 | Genealogy Notes

When Eli Whitney received his patent for the cotton gin 210 years ago, he little realized how this simple mechanical device would transform the American South and the face of the nation. He had originally thought that reducing the amount of manual labor in processing cotton might spell an end for slavery, but the consequences of his invention were quite different.

In 1793, while a guest of Catherine Greene at her Georgia plantation, Whitney learned that the planters in the area could not make a profit from growing short-staple cotton because the process of removing the sticky seeds was so time-consuming. Long-staple cotton, which was easy to separate from its seeds, could be grown only along the coast. Cotton gins (“gin” is short for “engine”) had been around for centuries, but Whitney’s machine was the first to clean short-staple cotton.

It was a simple machine: a wooden box that spun cotton around a drum and picked out waste with wire hooks. Picking the seeds by hand, one worker required several hours to produce one pound of fiber. A single cotton gin could produce up to fifty pounds of cleaned cotton in a day.

Whitney hoped to make a fortune from his invention. He and his partner, Phineas Miller, intended to build and operate gins and charge farmers for their use, but cotton growers objected to the fees and built their own versions of the machine. Whitney received his patent on March 14, 1794, but by then, a number of pirated versions of his cotton gin were in use.

Struggling to make a profit and mired in legal battles, the partners finally agreed to license gins at a reasonable price. In 1808 and again in 1812 Whitney petitioned Congress for a renewal of his patent.

The yield of raw cotton doubled each decade after 1800. By mid-century, America was growing three-quarters of the world’s supply of cotton, most of it shipped to England or New England, where it was manufactured into cloth.

Cotton growing became so profitable that planters rapidly increased the number of acres devoted to the crop and the number of slaves to tend and harvest it. In 1790 there were 697,624 slaves in the United States. Twenty years later, that number rose by nearly 70 percent to 1,191,362, and it steadily increased through the decades. By 1860,the census showed nearly four million slaves in the country, with the great majority in the southern states.

Whitney’s simple machine—a box containing rotating cylinders with rows of wire teeth—had profound consequences for the course of U.S. history. Not all of them were what its inventor had in mind.