AAD: A New Tool to Search NARA Databases

Spring 2003, Vol. 35, No. 1 | Spotlight on NARA

By David R. Kepley

You probably had someone in your family like Uncle Ted. He was the life of the party, the source of great family stories.

You knew he had served in the Pacific during World War II because that's what everyone had always said. But whenever you had asked him about it, he would change the conversation. After he died last year, you decided to learn more about him and his time in uniform.

After talking with friends, you learned that the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) maintains records of Americans who served in the armed forces. While exploring NARA's web site (www.archives.gov), you came across something that looked promising—the Access to Archival Databases (AAD) system.

One of the databases in AAD had information about Americans who had been prisoners of war (POWs) in World War II. Although no one had ever said Uncle Ted had been a POW, it could explain why he didn't like to talk about the war. You decided to give it a try. You brought up the search screen and typed in his name.

The search results page found three people with Uncle Ted's name, so you picked the one with his serial number. The record indicated he had been captured by the Japanese after the fall of the Philippines. He had survived the infamous Bataan Death March, where thousands of Americans and other Allied nationals had died under horrific circumstances. No wonder he never wanted to talk about being a POW. At the next family gathering, you share what you learned about your uncle.

Although this scenario is fictitious, it illustrates how NARA has vastly improved public access to some of its most popular electronic records.

Had this scenario been run just a few months ago, the process would have been much different. You would have asked NARA by telephone or in writing if there was any information about Uncle Ted. NARA's archivists would have looked up the information for you and provided a reply in a week or two, but it could have been longer if they had to ask you questions to clarify the request. And you would have had no opportunity to browse the records to see other items of interest.

What has made the first scenario possible is AAD, which can help ordinary citizens gain ready access to essential evidence of how the government has touched their lives.

AAD is the first publicly accessible application developed under the auspices of NARA's Electronic Records Archives (ERA) program. AAD has been designed and built to provide the public with access to a certain type of electronic record in NARA's holdings—databases.

The overall ERA program is charged with developing a way to preserve the increasing variety and volume of electronic government records that are being created at an explosive pace and to make them accessible to anyone, anywhere, anytime. To learn more about the ERA, go to www.archives.gov/electronic_records_archives/index.html on NARA's web site.

"With the unveiling of this application, NARA has taken another step toward our Strategic Plan goal," said John W. Carlin, Archivist of the United States. "In the Plan we promised to 'make it easy for users to access [essential] evidence regardless of where it is, where they are, for as long as needed.' The electronic records in AAD are available to any researcher with access to the Internet at any time of the day or night."

The story of AAD began in the summer of 1999, when most people who thought about computers were devoting most of their attention to the Year 2000 problem. During that summer, NARA contracted with Science Applications International, Inc. (SAIC) to develop a generic application that would permit people to search and retrieve information from old government-produced databases through the Internet.

SAIC's engineers and NARA archivists found the task anything but easy. The databases selected for initial inclusion in the project were ones that had been popular with the researching public. The problem was that while they had all been converted to a common file format before being transferred to NARA, each exhibited its own peculiarities.

For example, several old Defense Department databases used a code known at the time as "zoned decimal." This was usually a letter at the end of a number that could indicate a specific characteristic, such as whether it was a positive or negative number. Understanding what each code meant and displaying it in a way that was both faithful to the original record and meaningful to the average person challenged AAD team members.

In its initial rollout this year, AAD included more than four hundred databases created by more than twenty different federal agencies. These databases collectively contain more than fifty million unique records— casualties from the Vietnam and Korean conflicts, indexes to NASA photographs, insider securities trading transactions, contracts between the private sector and the military, records of people immigrating to America during the Irish potato famine of the 1840s, and records of Japanese Americans interned during World War II. (See accompanying list.)

Depending on demand and resources, the agency may add more databases in future years. Nonetheless, given the time and effort involved in preparing records for AAD, the number of databases NARA includes in AAD will always be a small fraction of the databases that NARA has preserved. This is because NARA is concentrating efforts on the development of the ERA system, which will provide access not only to historical databases but also to an unlimited variety of electronic records documenting our national experience.

Using AAD is easy. Go to http://aad.archives.gov/aad/. AAD's home page has links that describe the project and provide users with some tips on how to use the application, including a context-sensitive help file and a glossary.

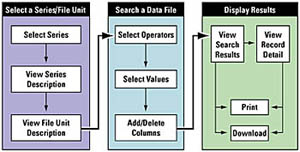

After clicking on the Search button, you can find information in AAD by following this process: Select a database to search, search it, and display the results.

The following example, however, might help you visualize how the research process might work. Suppose you wanted to locate the record of Quentin Smith, who you believe was wounded while serving in the army during the Korean War.

Start by clicking on the Search button on the AAD home page. This will bring up the Select a Series/File Unit page.

(There is a step-by-step sample search on the AAD "Getting Started" page.)

Because AAD does not permit you to search more than one database at a time, this page is designed to help you determine which database might have the information you seek. To help you figure this out, NARA's archivists have organized AAD's databases into eight broad categories (see sidebar).

Since you seek information about a person, Quentin Smith, you select the "People" category. This brings up a list of series, which includes the following: Korean Conflict Casualty File, 11/1976–11/1979, and Korean War Casualty File, ca. 1950–ca. 1970.

When you click on the link to the first one, you see in the scope and content note that this relates to people who were killed in the Korean War. Since you know that Quentin Smith survived the war, you go back to the other series. When you click on its series description, you learn that this one records the names of those army personnel who were casualties during the war. This looks promising, so you click on the "search" option.

Now you have moved into the second or "search" stage of the research process. The Search page has a gray box at the bottom that contains a selection of some of the fields in this database. NARA's archivists have selected these fields as the ones that you will most likely want to use for your search.

If you want to add more fields, you could click on the "Customize Search" link. You notice, however, that one of the fields is "Name of Casualty," so you type "Quentin Smith" into the "Enter Values" box and click on the "Search" button.

This brings us to the Search Results page.

At the top of the Search Results page, you see that there is only one Quentin Smith in this database. When you go to the bottom of the page, you see the record itself, most of which is in the code the army used.

So, for example, it will tell you that the place of the casualty was "LN." Without the army's code book, however, you will probably have no idea what that means. You check the "Select Record" box next to Quentin R. Smith's name and click on the "Show Selected Records" button. This brings up the Record Detail Page.

Here NARA's archivists have translated for you all of the codes that the army provided to NARA.

In the case of our Quentin Smith example, AAD shows that on March 28, 1953, Pvt. Quentin R. Smith of Franklin County, Maine, was "wounded in action by missile" and was "hospitalized." Here you also learn the code "LN" stands for "North Korean Sector." It further indicates that he returned to duty on June 30, 1953.

You print out the page using the print feature on your browser. Your search of AAD was successfully completed.

AAD serves an important role in furthering NARA's core mission, one that is at the heart of all its programs and activities: NARA ensures, for the citizen and the public servant, for the President, and for the Congress and the Courts, ready access to essential evidence.

How do I find the databases I want?

David R. Kepley is an archivist working for the Operations Staff of the Office of Records Services–Washington, D.C., National Archives and Records Administration. He has been with the National Archives since 1976. The author has been the project manager for the AAD project since its inception. He is a graduate of the Advanced Management Program given by the Information Resources Management College of the National Defense University. He also holds a Ph.D. in American history from the University of Maryland.