“Blisters on My Heels, Corns on My Toes”: Taking the 1930 Census of Population

Winter 2002, Vol. 34, No. 4 | Genealogy Notes

By David M. Pemberton

W. C. Bailey, a census supervisor for the 1930 census in San Jose, California, acknowledged that most of the letters he received in the course of his duties as supervisor were "complaining ones."1 For example, in response to a question from Bailey, one census taker stated that the individual living at one address on Hollywood Avenue in San Jose had been enumerated and continued, "This guy lives in a garage which looks the part. . . . I can hardly apologize for neglecting to peek into all the garage windows in my district for a man instead of a bus."2 However, a few actually had something positive to say about the census. One woman told Bailey, "I have walked blisters on my heels, corns on my toes, and nerves and muscles to exhaustion to secure a 100% census of my district. When I secure a few more names on Monday, who are now out of town, I will have succeeded. AMEN!!!"3 Another enumerator noted: "If the others enjoyed the work half as much as I did, they had a good time. The season, the lovely days out of doors, the work in economics study, the endless number of new things one could see and learn; all these go to show that it was an opportunity for a most interesting study. As for me, I found as much of interest outside the [enumerator's] portfolio as inside."4

The circumstances in which the 1930 census was taken were not propitious. Less than six months before Census Day (April 1, 1930), the stock market crash of October 1929 brought what Alan Greenspan might have called a period of "irrational exuberance" to an abrupt halt. As the effects of the crash worked their way through the American economy, tens of thousands of workers in the financial, manufacturing, construction, and wholesale and retail trade sectors of the economy were thrown out of work.5 To make matters worse, American agriculture had been in a depression since the early 1920s.

As the "Roaring Twenties" gave way to the "Hungry Thirties," census officials also had to deal with the failure of the U.S. House of Representatives to fulfill its constitutional responsibility to reapportion seats among the states based on the results of the 1920 census. The causes of congressional inaction involved sectional conflicts (the largely rural, agrarian south versus the industrial northeast and midwest), racial strife, anti-immigrant sentiment, and the divide between urban and rural communities and ways of life. Following nearly a decade of debate, Congress passed, and President Herbert Hoover signed, legislation authorizing the 1930 census on June 18, 1929. This law also contained language that cleared the way for reapportionment to take place based on the 1930 census.6 While the Census Bureau was not responsible for the foot-dragging, one result was to raise serious questions about the capacity of government to carry out its duties.

Following the 1920 census, the Census Bureau's director, William Mott Steuart, concluded that designating January 1 as Census Day had been a mistake. He pointed out that the weather in January 1920 had been "especially severe," had resulted in many delays, and had required taking "unusual precautions" to assure the completeness of the census.7

Accordingly, one of Steuart's recommendations concerning the next census was to move Census Day from the dead of winter back to the spring.8 However, setting the reference date for the census was, and is, a congressional prerogative. The designation of April 1, 1930, as Census Day had to wait for the passage of the authorizing legislation in 1929.9

In the meantime, Census Bureau officials began planning in earnest. In 1927 Steuart noted: "There has been a constant pressure to postpone this preliminary work, and it is safe to say that at no decennial census have satisfactory preliminary arrangements been made."10

One of the largest tasks was to divide the United States into 120,105 enumeration districts, or areas that could be canvassed by a single census taker. In 1927 the Census Bureau began the arduous job of acquiring or preparing accurate, current maps of every city and county in the country. The agency's plan involved contacting knowledgeable people in each of the nation's approximately 65,000 states, counties, cities, townships, and other political subdivisions to inquire about the availability of maps and possible boundaries for enumeration districts.11 While local residents provided helpful suggestions and valuable information, the Census Bureau's professional staff was responsible for determining, plotting and describing enumeration district boundaries; taking into consideration the terrain, population density, and amount of territory an enumerator could cover in the time allotted; and assuring that no boundaries overlapped or left missing areas.12

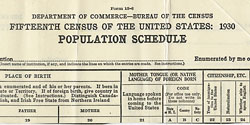

The 1920 census schedule was the starting point for determining the information to be collected in 1930. For the first time, the Congress did not prescribe in detail the questions that were to be asked in the census; however, it did specify the broad areas that were to be investigated. The number and the wording of the specific questions were left to the discretion of the Census Bureau's director, with the concurrence of the secretary of commerce. Census officials consulted with the members of the agency's standing advisory committee (composed of representatives of the American Statistical Association and the American Economic Association), and requested advice from a conference of experts on the population census. Most of the questions asked in 1930 were similar to those used a decade earlier. After considering a list of about forty new inquiries, Census Bureau experts decided on six new questions:13 two each on housing topics (value of the home, if owned, or monthly rental, if rented; and the presence or absence of a radio set in the home), demographic issues (age at first marriage [for married people only] and whether actually working14), and veterans' concerns (veterans' status and the campaign in which veterans had fought.)

Each of the added questions was designed for a particular use. The items on veterans' status were added at the request of the Veterans' Bureau, probably to estimate future costs associated with veterans' pensions and related programs. The information on the value of homes owned or monthly rent served as a proxy for income and allowed for the classification of families by economic status or buying power. The growing advertising and marketing industry was sophisticated enough to be able to use this information to design advertising campaigns for a variety of products and services.15 Information on the number and distribution of radios was used by the Federal Radio Commission to allocate radio frequencies around the country and to help improve radio reception. The press release on this topic stressed that "The question has absolutely no connection with possible taxation or any other associated idea."16 Steuart added, "Equally foolish is the idea that the Census Bureau is attempting to assist the sales departments of private radio companies by letting them know which specific families do not own radios."17

Of course, some of the suggestions for new questions were of the tongue-in-cheek variety. One writer for a South Carolina newspaper suggested that the 1930 census "neglected to put in many questions that the present age demands. . . . How much did you lose in the stock market crash last fall? If you could live your life over, would you get married? What is your average golf score? If single, how much do you spend on girls a year? Are you a native born or naturalized Democrat? How do you pronounce the name 'Aristide Briand?'"18

To make room for the new questions, the inquiries on the mortgage status of owned homes, date of naturalization, and native language of mother and father were dropped, and two questions on the ability to read and to write were combined into one.19

To alert the population to the coming census, the Census Bureau began designing its publicity program in 1928.20 This program began with efforts to inform the public about the general purpose for conducting the census as well as an explanation of the types of questions to be asked. Such information came to the public through a series of press releases and articles intended for publication in newspapers and magazines. In federal buildings, a presidential proclamation was distributed and displayed that stressed each individual's duty to respond to all questions; informed people that the census had no relationship to taxation, military conscription, jury duty, or compulsory school attendance; and reminded respondents that the information they provided would be held in strict confidence. And with the final publication of the printed reports, over a year after Census Day, the Census Bureau released a second set of press releases designed to highlight and explain the significance of the major findings of the census in both tables and text.

The Census Bureau, however, did not rely solely on the printed media to mobilize the public. Perhaps taking a cue from the "admen" of the private sector, the Census Bureau worked to appeal to the public in a variety of ways. In addition to asking local newspapers to announce the names of those selected to be supervisors and enumerators, it sought the cooperation of radio stations and movie theaters in promoting the census. The Census Bureau also appealed to local chambers of commerce and other community organizations to encourage the members of their communities to complete the census.

Another useful resource for education, promotion of the census, and recruitment was in the schools. Beginning in late 1929, the Census Bureau designed an outreach program aimed at the National Education Association to urge teachers to explain the census to their students. Students would then write an essay that they would take home to show their parents. In addition, the Census Bureau encouraged teachers, substitutes, and advanced students to become enumerators.

The Enumeration

The area covered by the 1930 census included the 48 states, the District of Columbia, and the territories of Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands of the United States, Panama Canal Zone, Guam, and Samoa.21 Census Day for all areas was the same except in Alaska, where the census was taken as of October 1, 1929, for "climatic" reasons. Territories accounted for approximately 1,700 enumeration districts.22

The transition from preliminary planning and preparation to early census operations had begun by mid-1929, when the Census Bureau started to identify candidates for the 575 census supervisor positions. The agency received a waiver from civil service laws for the hiring of supervisors and enumerators. This allowed the bureau to accept applications from political referrals as well as those from people without political credentials. Steuart reported that by June 1929, bureau headquarters was receiving applications for supervisory positions on a daily basis. Upon receiving an application, the agency sent the inquirer the fifty-page supervisor's manual with a letter asking him or her to read the manual and inform the agency if they were still interested. Not surprisingly, some applicants withdrew their applications upon finding out what the duties involved. Among other responsibilities, each supervisor would be responsible for overseeing the activities of an average of 170 enumerators.23

Applicants who survived this part of the process were sent an application blank, a test census schedule, and a descriptive narrative of a small population. They were to complete the application and the census form with facts contained in the narrative and mail the formal application package to bureau headquarters. There, agency officials corrected the test and sent a photostat of the corrected version to the applicant. If the person passed the test and could demonstrate having had business training or other qualifications for supervisory work, he or she was offered the position. Supervisors were expected to live in or near the city in which the supervisor's office was established. Thirty of the 575 supervisors appointed for 1930 were women.24

Once appointed, one of the supervisor's first responsibilities was to acquire office space and equipment, at no cost to the bureau wherever possible. Supervisors were instructed to seek assistance from the local Federal Business Administration and to request space, office equipment, and furniture from federal, state, and municipal agencies and from civic organizations such as chambers of commerce and boards of trade. Success in these endeavors varied widely. More than half the supervisors (346) were able to secure free office space, but less than a quarter (141) got free office equipment. In the balance of the offices, the agency was forced to rent space and rent or purchase the necessary equipment and furniture.25

Census supervisors were delegated the authority to hire and fire enumerators. Initially, all applications for enumerator positions were to be sent to bureau headquarters. Aspiring census takers were sent the same test census form, instructions, and narrative mailed to supervisors, as well as an application form, and asked to complete the census schedule using the information in the narrative according to the instructions. Enumerator packages were graded and corrected in Washington, and those that passed were sent to the appropriate supervisor. By March 1930, the number of enumerators needed and the tight time schedules led to an updated procedure in which applicants sent their completed packages directly to the supervisor's office, where they were graded and corrected.

Bureau officials estimated that they would need about 100,000 enumerators to take the census. In the end, the agency hired 87,800 enumerators. Of the nearly 198,000 people who applied for these positions, 157,000 were judged qualified.26

Enumeration districts in cities comprised an average of eighteen hundred people. Enumerators were expected to complete their work in the two weeks from April 2 to April 15. For rural areas, enumerators administered the agriculture census as well as the population census, and the districts contained fewer people. But because the area covered was much larger, rural enumerators were given four weeks to collect their data.

Enumerator pay varied in different parts of the country but was usually four or five cents for each person enumerated and forty or fifty cents for each farm. In exceptional circumstances, the rates went as high as twenty cents a person and five dollars a farm. The goal was to allow the average enumerator to earn between five and eight dollars a day during the enumeration.27

In addition to overseeing the work of the enumerators, census supervisors were also authorized to appoint an office staff. Usually hired in February or March 1930, the office staff consisted of two office supervisors, a stenographer, and up to ten clerical workers. Supervisory personnel earned between $4.00 and $6.00 a day; stenographers were paid $5.00 a day. Pay for clerical workers varied between $2.50 and $4.00 a day but could reach as much as $10.00 a day.28

Any number of factors could contribute to delays. In some parts of the Southwest and the far West, enumeration districts encompassed more than 150 square miles of rugged terrain. One enumerator working out of Butte, Montana, said that he had ridden six hundred miles on horseback between March 29 and April 23 in order to count the three hundred people in his district.29 In neighborhoods heavily populated by immigrants, suspicion of outsiders and the government in general made it virtually impossible for anyone but a local resident to obtain complete and accurate information. While the Census Bureau tried to hire locals in most cases, it was not always possible. While 291 translators were hired to assist with the enumeration, this was obviously an inadequate number for a foreign-born population of 14.2 million people.30 Despite these difficulties, most of the census data were collected within the time allotted.

After the office staff had reviewed the completed schedules returned by the enumerators, supervisors were told to release preliminary counts for as many civil divisions areas in their districts as possible. By mid-April, supervisors throughout the country had begun to release the figures. Two months later, preliminary counts for 745 cities and towns of 10,000 or more and for more than half the 3,098 counties had been released.31 Local officials were anxious to have these figures, and a few even complimented supervisors on the quality of the count in their areas. For example, the mayor of Santa Cruz, California, wrote to the local census supervisor to thank him for releasing the preliminary count for his city, adding "Your work should be commended."32

The official count of state populations for the purpose of apportionment were given to the secretary of commerce on November 17, 1930; he in turn sent them to President Hoover, who forwarded them to the Congress on December 4.33

Data Tabulation and Publication

Following a clerical review in the district supervisor's office, completed census schedules were sent to Census Bureau headquarters in Washington for further editing, coding, keying, and tabulation. Once the schedules were received at headquarters, they were reviewed for omissions and internal consistency. The next step in the process was adding the codes for occupation, birthplace, language, and other variables. Once the clerks supplied these codes, the schedules were ready for keying.

The tabulation system required that two cards be punched for each person. One card carried all the information noted on the individual census schedule, except age at marriage, which was included on the family card. The second, a family card, included the composition and characteristics of the family taken from the census schedule. A third card, the unemployment card, was prepared for each person who was usually employed but was not at work the day before the enumerator conducted the interview.34

The Census Bureau employed about two thousand people and up to 2,225 punching and verifying machines to keypunch over 139 million cards for the 1930 census of population.35

After keypunching, the cards were sent to be sorted and tabulated by machine. The sorting machines the bureau used could sort only one column at a time. While some tabulations were run without prior sorting, many of the card decks had to be sorted frequently to separate the subsets of information needed for a particular table. Groups of cards moved from the sorting machines to the tabulators.36 Unit counters (a kind of tabulating machine) added up the number of people in a given geographic area who had the specific characteristics called for in a particular table. Typical combinations included marital status by sex and race, and literacy by age. The end product of each tabulation run was a large sheet of paper with printed counts of the number of people in each of several groups defined by their characteristics. Each run covered a limited geographical area, such as an enumeration district. To obtain publication data, the results of two or more runs would be aggregated into publication geography, such as counties, cities, and minor civil divisions. As Secretary of Commerce Robert J. Lamont pointed out, each card had to be run through the electric tabulating machines "a dozen times or more" to extract the data presented in census publications.37 Nearly four thousand people worked in the sorting and tabulation area during the height of the 1930 census.

The entire 1930 census produced thirty-three volumes of data, including six volumes of population data and two of unemployment information. The number of published pages amounted to 35,700. The bulk of this was published within the decennial period, which extended from January 1930 through December 1932, although several volumes were printed in 1933 and 1934. At least one volume of 1930 data was published as late as 1937.38

As one might expect, many of the demographic trends revealed by the 1930 census were continuations of those that had made the reapportionment fight over the 1920 census so bitter and protracted. The proportion of the population that lived in cities of 100,000 people or more increased from 25.9 percent to 29.6 percent between 1920 and 1930. The total urban population grew from 51.4 percent to 56.2 percent.39 The fastest growing region of the country was the West. The big winner in the reapportionment that followed the 1930 census was California, which gained nine seats in the House of Representatives, nearly doubling the size of its congressional delegation.40

The Last "Traditional" Census

In several ways, the 1930 census can be thought of as the last traditionally conceptualized and organized census.41 Beginning in 1940, a census of housing was added to the census of population in order to determine the extent of the nation's housing needs in the wake of the Great Depression. Millions of people had been forced out of their homes by mortgage foreclosure, repeated crop failures, and forced migration. Millions more lived in dwellings that lacked heat, electricity, or running water. The housing census helped clarify the scope and geographic distribution of this problem and forced public officials to develop ways to alleviate it.42

The 1930 census was the last to ask virtually all questions of the entire population. The inclusion of probability sampling in the census was another innovation for 1940. Probability sampling could not have been included prior to 1940 because the methodology of applying it to human populations was developed during the 1930s. By incorporating sampling methodology into the census, it became possible to obtain accurate, detailed information, with known margins of error, without unduly increasing respondent burden and at relatively little added cost.43

The 1940 census was the first to include a question on income. Many observers believe that one of the causes of the depression of the 1930s was the maldistribution of income. They believe that an economy that produced more goods and services than its people could consume or than could be exported was structurally imbalanced. Although the initial effort to include income in the census was relatively limited (asking only for the amount of money wages or salary up to five thousand dollars and whether the respondent received more than fifty dollars from sources other than wages or salary) and met with substantial resistance from legislators and portions of the population, the income question has become a standard inquiry in censuses ever since.44 For those not willing to tell the enumerator their income, the 1940 census included a confidential income report form that allowed respondents to mail their answers to the income question to the Census Bureau.45 To reduce opposition further, the question was moved from the 100-percent part of the census to the sample in 1950.

Finally, the 1930 census was the last one that did not include an effort to obtain quantitative assessments of how comprehensively the census had counted the population. The initial quantitative evaluation of the 1940 census consisted of comparing aggregate data on the number of men who registered for the draft during World War II with 1940 census data on the number of men in the same age group. The study concluded that the census contained an undercount of males of draft age and that the undercount was significantly higher for African Americans than for Whites.46 Beginning with the 1950 census, all American population and housing censuses have included quantitative evaluations of census coverage.

In spite of all the improvements that have taken place in American census taking since 1930, the process of obtaining information from people who do not respond voluntarily remains fundamentally the same. It involves identifying, testing, hiring, training, and sending tens of thousands of enumerators onto the streets of the cities, towns, and hamlets of the United States to knock on doors, ask the questions on the report form, record the responses, and send the completed questionnaires to facilities where they are aggregated, tabulated, and released to the public to be used and misused in the innumerable ways that Americans have devised since the data from the first U.S. census were published in 1791.

Notes

I would like to thank Connie Potter and Bill Creech of the National Archives for helping me locate the records used to prepare this article. Bill Maury, chief of the History Staff of the Bureau of the Census, supported this project, carefully edited the draft, and redistributed office work to give me time to complete this article. The Census Bureau's reviewers included Tom Jones, Jerry Gates, Campbell Gibson, and Tommy Wright; I want to thank them for giving of their time and expertise. Michele Freda and Cathie Childress of the Census Bureau's Public Information Office helped me find and duplicate the photographs reproduced in this article. My colleague, Shannon Parsley, helped with all aspects of this work including brainstorming, editing, and photo selection, and contributed mightily to its completion.

This paper reports the results of research and analysis undertaken by the U.S. Census Bureau Staff. It has undergone a Census Bureau review more limited in scope than that given to official Census Bureau publications. This report is released to inform interested parties of ongoing research and to encourage discussion of work in progress.

1 W. C. Bailey to Director of the Census, June 16, 1930, Entry 215, box 231, Record Group (RG) 29, National Archives Building (NAB), Washington, DC. Many complaints dealt with pay. A number of letters to Bailey echoed the comment of Oliver Butterfield, who wrote, "The pay we will receive for this work is not in keeping with the efforts the enumerator must use to complete it; why our government expects a complete census for such a small wage is beyond me." Butterfield to Bailey, Apr. 16, 1930, Entry 215, box 231, RG 29, NAB.

2 S. J. Norton to Bailey, Apr. 19, 1930, ibid.

3 Anna M. Pevoto to Bailey, Apr. 19, 1930, ibid.

4 Bessie L. Erickson to Dr. Bailey, May 13, 1930, ibid.

5 The literature on the causes of the depression of the 1930s is vast and contentious. A good, recent overview of the depression in the United States is David M. Kennedy, Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945 (1999), pp. 10–103. A broader account that discusses both the European and American contexts and that emphasizes multiple causation is Charles P. Kindleberger, The World in Depression, 1929–1939 (rev. ed. 1986).

6 See Margo J. Anderson, The American Census: A Social History (1988), chap. 6. The text of the law authorizing the 1930 census is in U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Census Bureau Legislation, comp. Robert H. Holley (1936), pp. 29–37.

7 U.S. Bureau of the Census, Annual Report of the Director of the Census to the Secretary of Commerce for the Fiscal Year ended June 30, 1921 (Annual Report, 1921) (1921), p. 30.

8 For the 1910 census of population, Census Day was April 15; between 1830 and 1900, Census Day had been June 1.

9 April 1 has remained Census Day since it was first designated as such in 1930.

10 Annual Report, 1927, p. 2.

11 Annual Report, 1928, p. 2; Annual Report, 1929, p. 2; Joseph A. Hill, "Progress of Work in the Census Bureau," Journal of the American Statistical Association (December 1927): 511. For some cities no maps were available; bureau officials had to obtain descriptions of enumeration districts from local residents. See Annual Report, 1928, p. 2. By mid-1929, the Census Bureau had contacted about 85,000 people and received information useful for delineating enumeration districts and for establishing local enumerator pay rates.

12 Annual Report, 1927, p. 2; Joseph A. Hill, "Progress of Work in the Census Bureau," pp. 510–512.

13 Leon E. Truesdell, "The Census of Population," Journal of the American Statistical Association, 25, Supplement (March 1930): 113–116; Annual Report, 1929, pp. 4–7.

14 A special unemployment questionnaire was administered to individuals who usually worked but were reported as not at work in the census.

15 Truesdell, "The Census of Population," pp. 113–114.

16 U.S. Census Bureau, "Why the Radio Question Was Included in the Census," n.d., Entry 215, box 232, RG 29, NAB.

17 W. M. Steuart, "Value of Census Figures Greatly Improved," n.d., Entry 215, box 233, RG 29, NAB.

18 Strong Cigar, "Be Ready for Census Man," The News and Courier (Charleston, SC), Mar. 21, 1930.

19 Truesdell, "The Census of Population," p. 114.

20 Annual Report, 1930, p. 2; [Joseph A. Hill], "Publicity: Tentative outline, November 26, 1928," Entry 215, box 232, RG 29, NAB.

21 Bureau of the Census, Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930: Population (1931), vol. 1, p. 2. Although the Philippine Islands were a territory of the United States, they were not included in the 1930 census. The commonwealth statistical office sponsored a Philippine census in 1939. In addition to a canvass of the population, the 1930 census collected data on agriculture, irrigation, drainage, manufactures, mines, distribution or trade, construction, and unemployment.

22 Annual Report, 1930, p. 10.

23 Annual Report, 1929, pp. 3–4.

24 Ibid.; Annual Report, 1930, pp. 4–5.

25 Annual Report, 1930, p. 5.

26 Ibid., pp. 7–8; Joseph A. Hill, "Progress of Work in the Census Bureau," Journal of the American Statistical Association (March 1929): 1. Since at least 1880, the suggestion has been made that letter carriers should take the census. Legal changes allowed some letter carriers to be employed as enumerators in the 1930 census, but the experience was not a good one. For one thing, letter carriers had another job—delivering the mail. Completing census forms took time away from mail delivery. In Washington, DC, individual questionnaires were used instead of the large, 100-person forms. The information then had to be recopied onto the large forms, increasing the cost of the operation and the likelihood of copying errors. Despite the 1930 experiment, support for using letter carriers to collect census data continued. At the request of Congress, the Census Bureau and the U.S. Postal Service looked into this possibility early in the planning for Census 2000. In a joint letter report, the two agencies agreed that letter carriers did not know their postal customers well enough to complete their census forms, mail delivery would suffer, the cost of delivering census questionnaires would increase due to the higher wages and benefits of letter carriers, and legal changes would be required to allow postal employees to collect individual address information. See Samuel Green, Jr. (for the U.S. Postal Service) and Harry A. Scarr (for the U.S. Census Bureau), Letter of transmittal: USPS-Census Cooperation in Planning for the 2000 Decennial Census of Population and Housing. Nov. 5, 1993.

27 Annual Report, 1930, p. 7.

28 Ibid., p. 6.

29 The Butte Daily Post, Apr. 24, 1930.

30 Annual Report, 1930, p. 8.

31 Ibid., pp. 3, 8. The Census Bureau issued a press release on August 8, 1930, giving the preliminary population count of the United States as 122,698,190 (just under 77,000 below the official count of 122,775,046). See Annual Report, 1931, pp. 6–7. The release of preliminary counts was intended to allow for complaints to be investigated before the completed schedules were shipped to Washington and while enumerators remained on the payroll.

32 Fred. W. Swanton to Bailey, May 5, 1930, Entry 215, box 231, RG 29, NAB.

33 Annual Report, 1931, p. 1.

34 Robert P. Lamont, presentation at the seventeenth community meeting on the forthcoming Census of Manufactures and Distribution, Boston, MA, Jan. 4, 1930, Entry 215, box 232, RG 29, NAB.

35 Annual Report, 1931, pp. 5-6; Annual Report, 1932, p. 12. Another 150 million cards were punched in order to tabulate the other censuses taken concurrently with the population census.

36 Because of the addition of relays to the tabulating machines, many combinations of characteristics could be obtained without first sorting the cards. See, Leon E. Truesdell, "The Mechanics of the Tabulation of the Population Census," Journal of the American Statistical Association, 30 (March 1935): 93.

37 Robert P. Lamont, presentation at the seventeenth community meeting on the forthcoming Census of Manufactures and Distribution, Boston, MA, Jan. 4, 1930, Entry 215, box 232, RG 29, NAB.

38 U.S. Bureau of the Census, The Indian Population of the United States and Alaska (1937).

39 Leon E. Truesdell, "Growth of Urban Population in the United States of America," paper presented and the Population Congress of the International Union for the Scientific Investigation of Population Problems, Paris, July 1937.

40 Anderson, The American Census, p. 157.

41 See Edwin D. Goldfield, "Innovations in the Decennial Census of Population and Housing: 1940–1990," commissioned paper prepared for The Year 2000 Census Panel Studies, Committee on National Statistics, National Research Council, August 1992.

42 Goldfield, "Innovations in the Decennial Census," p. 25; Anderson, The American Census, p. 186; Robert Jenkins, 1940 Census of Population and Housing: Procedural History (1983), pp. 23, 38–39.

43 Goldfield, "Innovations in the Decennial Census," p. 19; Anderson, The American Census, pp. 182–186.

44 Those with incomes above five thousand dollars were instructed to write "more than $5,000."

45 Anderson, The American Census, p. 188.

46 Daniel O. Price, "A Check on Underenumeration in the 1940 Census," American Sociological Review, 12 (February 1947): 44–49.