Spoils of War Returned

U.S. Restitution of Nazi-Looted Cultural Treasures to the USSR, 1945–1959

Fall 2002, Vol. 34, No. 3

By Patricia Kennedy Grimsted

© 2002 Patricia Kennedy Grimsted

World War II resulted in the greatest loss and displacement of cultural treasures, books, and archives in history. As the German army occupied more and more of the European continent, Nazi cultural vultures swept up millions of items from museums, libraries, archives, and individuals. While Allied bombing reduced many cities to ruble, fortunately, the Germans had hidden away much of their cultural loot—and their own treasures—in remote castles, mines, and monasteries. Many of those treasures that survived never came home from the war. Depending on who found them, some were plundered a second time, and still others were dispersed throughout the world.

In the immediate aftermath of the war in Europe, with no agreement over restitution among the Allied victors, each of the four occupying powers in Germany and Austria—the United States, Great Britain, France, and the USSR—handled displaced cultural property that ended the war in their individual zones as they saw fit. The United States undertook an unprecedented program of cultural restitution in an effort to restore displaced treasures to the countries from which the Nazis had confiscated them.1

Simultaneously, Soviet authorities, in the name of "compensatory restitution," emptied museums, castles, and salt mines in Germany and Eastern Europe, transporting millions of cultural treasures (many earlier looted by the Nazis from Western Europe) to the USSR.2 Despite the Soviet "compensatory" cultural plunder in lieu of restitution, U.S. authorities in Germany returned more than half a million displaced cultural treasures and more than a quarter of a million books to the USSR that had been looted by the Nazi invaders.

This effort is documented in the recent CD-ROM publication from the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) on U.S. Restitution to the USSR, presenting facsimile inventories and related documents covering nineteen transfers between 1945 and 1959. Even now in Russia, however, many still deny such facts, just as Soviet authorities did in the immediate postwar years.

The issues remain unresolved today, as European nations still await the return of their twice-looted cultural treasures from Russia, while new laws and politicians in Moscow continue to block their return.

Soviet Spoils of War and Denial of U.S. Restitution

Soviet citizens never saw most of the Western cultural treasures brought home as spoils of war and never heard about American restitution. The Cold War and the Stalinist regime distorted the Soviet presentation of World War II and postwar developments to such an extent that even today, Western restitution of Nazi-looted cultural treasures to the USSR from occupied Germany and Austria remains a historical "blank spot." Not until the final years of glasnost in 1989 - 1990 did information gradually surface about the secret depositories for "trophy art" (as known in Russia), the millions of trophy books in an abandoned church outside of Moscow, and the kilometers of state and private archives from countries across Europe that had been held for half a century in the top secret "Special Archive."3

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the subject of restitution has been one of the most thorny issues in Russia's foreign relations. As European countries started to demand their cultural treasures and archives, Russian legislators prohibited restitution. They decided Russia needed a law "to establish necessary legal bases for realistically treating said cultural valuables as partial compensation for the loss to the Russian cultural heritage as a result of the plunder and destruction of cultural valuables by the German occupation army and their allies in the course of the Second World War."4 Nationalistic deputies in the Duma and a vast majority of the public believe that the trophies should not be returned.

In the midst of the four-year struggle over passage of the law, Russia was admitted to the Council of Europe in January 1996. In order to secure acceptance, among the commitments Russia was required to make were two specific "intents" for restitution of archives and other cultural treasures belonging to member states.5 Since that document was signed, Russia's parliamentary bodies have ignored those intents, a disregard that culminated in May 1997 with the almost unanimous passage of a law that potentially nationalizes all cultural treasures brought to Russia at the end of World War II— passed a second time over President Boris Yeltsin's veto. After Yeltsin was forced to sign the law in April 1998, the Constitutional Court upheld the law in a July 1999 ruling, and President Vladimir Putin signed amendments in May 2000.6 The conflicts about the passage of that law have created a virtual new Cold War with Western members of the Council of Europe.

The Russian law negates countless international conventions and resolutions adopted by the United Nations, UNESCO, and other bodies, as well as several bilateral agreements, calling for the restitution of plundered cultural treasures to their countries of origin. Since the amended law, Russia has established a new Interagency Council on Restitution with complicated and costly procedures for restitution based on claims from countries other than Germany and its wartime allies and, starting in 2001, a project for describing the displaced cultural treasures in Russia.7

The extent to which information about the postwar Western Allied restitution programs was suppressed—and even denied—in the Soviet Union was apparent in the press and parliamentary debates concerning passage of that law. Duma leaders adamantly assured legislators that Russia should legally be entitled to keep all of its extensive spoils of war—especially those seized from Germany and other Axis powers—because none of the Soviet cultural treasures looted by the Nazis had been returned from Germany. They claimed, "Now we are asked to return . . . what we received from the aggressor. We ourselves, we received nothing that had been taken away."8 There was often the implication, sometimes even explicit, that, if they were not still in Germany, then the Soviet cultural treasures plundered by the Nazis must have all been taken to America. Nikolai Gubenko, the former Minister of Culture under Mikhail Gorbachev who shepherded the law through the legislature, kept repeating to the press: "'Russia Has Been Robbed Twice'— first by Fascist Germany and then by its Allies. . . . Most of the displaced cultural treasures found at the end of the war in Germany, including the Russian ones, were transported across the ocean."9

Available documentation does not support such statements, yet they persist. As the Iron Curtain fell around the Stalinist regime and Germany was divided in two, information about the significant postwar cultural restitution by the Western Allies and the retrieval of Soviet cultural treasures and archives that did take place was never made public.

Nineteen U.S. Restitution Transfers to the USSR

Documents from the National Archives of the United States provide quite a different picture. Documents now published in facsimile on the NARA CD-ROM verify a total of nineteen U.S. restitution transfers to Soviet authorities between September 1945 and August 1959. Inventories with official transfer receipts (all signed by the Soviet receiving officer) list over half a million cultural treasures plundered by the Nazi invaders from Soviet lands found after the war in Germany and Austria. Initial facsimile copies were presented in Moscow in April 2000 at an international conference as the All-Russian State Library for Foreign Literature (VGBIL).10 The corresponding Soviet copies of those documents have still not been located in Russian archives.

When Soviet authorities complained about the lack of American restitution and the rejection of Soviet claims, the Restitution Division of the U.S. Office of Military Government in Germany (OMGUS) prepared a summary list in September 1948 of the first thirteen restitution transfers from Germany of Soviet cultural treasures plundered by the Nazis. An accompanying U.S. memorandum noted that the number of items returned to the USSR—over half a million—"amounted to a far greater number of items than the number of items officially claimed [by Soviet authorities]." That document was first published in Ukraine in 1991 11 and has since been published several times in Germany as part of a German study of U.S. restitution.12

U.S. restitution transfers were organized through the Central Collecting Points (Munich, Wiesbaden, Marburg, and Offenbach), where the Nazi loot found in the U.S. Zone of Occupation was assembled, although the first three transfers took place before those centers were organized.13

Transfers from Berlin, Pilsen, and Salzburg

The first transfer, consisting of archival materials, was turned over to Soviet authorities in Berlin on September 20, 1945—days after the U.S. policy directive on restitution was issued. That shipment comprised four freight-train wagons with 333 crates (1,000 packages) of "archival material removed by the Germans in 1943 from Novgorod" that had been "stored at the Preussisches Geheimes Staatsarchiv" (Prussian Privy State Archive) in Berlin-Dahlem.14

The second American transfer to the USSR, totaling approximately twenty-five freight-train wagons of archives and other cultural treasures plundered from Ukraine and Latvia, took place on October 25, 1945, west of Pilsen, in the part of Czechoslovakia liberated by the U.S. Third Army. Those treasures had been found in early May 1945 by the Americans in the Bohemian castle of Trpísty, northwest of Pilsen, and the nearby monastery of Kladruby to the southwest. That transfer consisted of extensive early archival records from the former Kyiv (Kiev) Archive of Early Records, rare early printed books and manuscripts from the Library of the Academy of Sciences (TsNB) in Kyiv, and even more extensive early archives and museum exhibits looted by the Nazis from Riga. The inventory of the Kyiv archival materials had been prepared and signed by the volksdeutsch Slavic scholar Nikolai Geppener, whom the Nazis had taken with the shipment. He turned down an American offer of asylum and insisted on accompanying those treasures back to Kyiv; after his return, however, he was persecuted as a Nazi collaborator.15

In a third transfer in December 1945 scientific materials from Smolensk were restituted to Soviet authorities in Salzburg, Austria. The receipt (dated December 5, 1945) records the transfer of "30 cases" containing "books, Herbariums, Minerals and Zoological-, Botanical-Collections," together with "3 large stuffed animals . . . and a special scientific Precision-Scales." It has not been determined if the materials were ever returned to Smolensk.16

The Munich Central Collecting Point

Six of the U.S. restitution shipments to the USSR, constituting large transfers of archaeological materials, treasures of the visual arts, and other museum exhibits, were processed through the Central Collecting Point (CCP) in Munich. The first director, Craig Smyth, memorialized operations there in a well-illustrated published account.17 The Munich CCP received the contents of the most important depositories in Bavaria that had been used for art treasures "saved" from Soviet lands by the so-called Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg, or ERR (Special Command Force of Reichsleiter [Alfred] Rosenberg), one of the most notorious Nazi agencies responsible for cultural looting. The three most extensive ERR depositories in Bavaria for treasures from the East were the Castle of Colmberg, near Lehrberg (Landkreis Ansbach); the Castle of Höchstädt (Landkreis Dillingen), near Augsburg; and the former Carthusian (Salesianer) Monastery of Buxheim, near Memmingen.

As the treasures of the visual arts and museum exhibits were brought to the American Central Collecting Points, property cards were prepared for individual items of significant value, or for lots of collected items, similar to the cards that had been prepared by the ERR during the war. In many cases, items were photographed at the collecting points, and most of those pictures have been preserved.18 Many of the ERR inventories of treasures from Soviet lands were recovered with the items themselves and helped CCP specialists determine the repository from which they had been looted. Some recently found ERR inventories even have the U.S. Munich property-card numbers added in pencil. Additional inventories according to presumed repository of origin were also prepared by CCP specialists in Munich.19

Despite the ERR inventories and efforts of overburdened Museum, Fine Arts & Archives (MFA&A) restitution officers, many of the property cards for art from the Soviet Union are not as detailed or accurate as desirable. As one blatant example, a portrait of Emperor Alexander I (ca. 1825) by George Dawe, probably from one of the imperial palaces near Leningrad, is listed as "Portrait of a general, standing (before landscape)." The art specialists (most with the ERR) involved in looting from Soviet lands often had neither good reference materials on which to base their own inventories nor time to prepare the detailed card descriptions for looted art. Soviet art historians were not on hand at the collecting points to monitor identification and descriptive work (although U.S. authorities had expressed willingness to receive specialists), and many of the Soviet officers who were sent to accept restitution shipments were not qualified museum specialists.20

Among the highlights in the Soviet Munich shipments were icons from many different churches in Novgorod and Pskov, twelfth-century mosaics from the Cathedral of St. Michael of the Golden Domes in Kyiv, collections of insects and herbaria from the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, and thousands of prehistoric archaeological finds from the Crimea. There were ethnographic exhibits from Kharkiv, Poltava, and Minsk; and treasures of the decorative arts from many museums in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus that had been found in Bavarian castles and monasteries.

The most notable Soviet restitution shipment processed through the U.S. Collecting Point in Munich (transfer #11 [Munich #5]) consisted of several freight cars with the Neptune Fountain from the Russian imperial palace in Peterhof outside of Leningrad (now again St. Petersburg). The Nazis had confiscated the fountain because it was a German production. The Americans found the dismembered fountain in a basement storage vault in Nuremberg and returned it to Soviet authorities. Restored with the missing components according to original drawings, the fountain now dominates the upper gardens in Peterhof. The fountain was last restored in 1997, but even today, tourist guides are unaware— or else never reveal— that the fountain was returned through the American restitution program.21

There were also two small shipments of importance to the USSR from the Wiesbaden Collecting Point, but fewer works of art from Soviet lands ended up there. A final transfer of 276 paintings and other treasures that took place in Berlin after the collecting points were closed down had been initially processed in Wiesbaden.22

Library Restitution from Offenbach

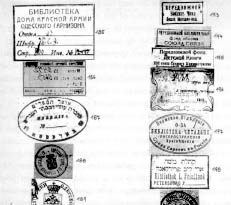

The major restitution shipments of library materials to the USSR were processed through the Offenbach Archival Depository (OAD) near Frankfurt, the centralized collection point and restitution center for books and archives in the U.S. Zone of Occupation.23 In what was undoubtedly "the biggest book restitution operation in library history," OAD processed more than three million displaced books and manuscripts (and related ritual treasures) between its opening in the winter of 1946 and its closure in April 1949. Offenbach restituted a total of 273,645 books to the USSR between March 2, 1946, and April 30, 1949, on the basis of confirmed library stamps, ex libris, or other markings.24 After the first shipment of eight freight cars on August 7, 1946, later shipments left Offenbach in October 1947 (329 crates) and December 1948 (14 crates), and a final transfer of books from Offenbach took place in Berlin in 1952.

As an essential ingredient in the identification process, photographs were prepared of all ex libris, book stamps, and other markings found in the books arriving for processing so that sorting could be done by collection and library of provenance.25 The system was hardly foolproof, however, as remaining OAD reports and the albums themselves make clear. Knowledgeable Soviet library specialists did not come to Offenbach to assist with identification, as was the case with some other countries. And, unfortunately, nobody at OAD knew Slavic languages well, nor did they understand the complexities of Soviet library reorganization and the migration of Russian, Belarusian, Ukrainian, and Polish collections (including many Jewish ones) in connection with post-revolutionary Soviet nationalization and wartime international border changes. Hence, it is not surprising that we find many Ukrainian library stamps listed under "Russia—'Russland'" and others in the "Poland" section in the OAD albums. Such discrepancies explain why many books plundered from Ukraine by the Nazis and restituted to the USSR by the United States were never returned to Ukraine. Recent tributes to OAD operations usually do not mention these identification and distribution problems, which still need more thorough analysis.

While over 275,000 volumes were returned to the USSR from OAD, many more books were returned from other collecting points as well. As late as 1962, the West German government transferred nine crates of books found in the library of the University of Heidelberg to the USSR, comprising scientific and technical books from Kyiv, Voronezh, and some from unidentified libraries. It is not known if those had come through OAD, although book stamps from Voronezh appear in the OAD albums.26

Return of War Booty from the United States

Two later transfers took place in Washington, D.C., involving cultural property illegally brought back to the United States as war booty. In April 1957, Ardelia Hall, who headed the American restitution program in the Department of State, personally transmitted thirty-one icons to the embassy of the USSR in Washington. The icons (presumably from a village in Ukraine) had first been looted by a Nazi SS officer and then looted from the basement of a hospital in Halle, Germany, by an American army captain. When he tried to send his booty to the United States in two separate shipments, they were seized by U.S. Customs in Texas. Restitution of the icons to Soviet authorities was delayed because of a significant protest (with a petition from parishioners) from a local priest of the Russian Orthodox Church in America:

Only too vividly can I recall the period when Soviet government personnel . . . seized many an ikon collection such as this . . . and burned them in huge bonfires on the streets. . . . [A]ccounts reach us even today of the anti-religious feeling in the Soviet Union. . . . I am too unhappily concerned that these ikons, or any others returned to the Soviet Union would never reach a church, but would be confiscated immediately. . . . It is therefore my heartfelt plea that you do whatever you can to prevent the return of these ikons to the Soviet Union and their destruction.27

The State Department nevertheless insisted on restitution. Interestingly, documentation has surfaced recently in Moscow showing that, on May 31, 1957, the Soviet embassy in Washington turned over the icons to Archbishop Dionisii, then the acting representative of the Moscow Patriarch in the United States. Soviet authorities had determined that the icons were not of great value or historical interest.28 The present location of the icons has not been determined, but presumably they remain in the United States.

Two years later, a collection of thirty-one prehistoric bone artifacts was identified in the American Museum of Natural History in New York as having markings from an archaeological collection in Kyiv. The artifacts had first been removed to Cracow and thence taken to the Castle of Höchstädt in Bavaria. The circumstances of their illegal removal from Germany to the United States is not known, but they were presented by an army widow from Georgia to the museum, where their provenance was traced, undoubtedly in response to appeals by the Department of State for looted cultural treasures illegally brought to the United States. Formal restitution to the Soviet embassy in Washington, DC, took place on August 18, 1959. In October 1959 the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the USSR turned over the returned artifacts to the president of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR, A. V. Paladin.29

Statistical Approximations

The total units of cultural treasures and archives returned in those nineteen transfers comes close to 540,000, while the initial 1948 U.S. list of thirteen shipments totaled approximately 534,170 items.30 Indeed, that total figure was significantly understated because an item could denote a single painting or several pieces. On inventories that accompanied the nineteen official U.S. custody receipts, one item could denote a set of 35 - 50 glass vases, 240 books, or 26 Russian manuscripts. In the case of the Austrian transfer, the figures were for large crates of books rather than volumes. Complete records of the American transfers, including the accompanying inventories, have long been open to the public in the United States and Germany, although the actual documents are difficult to find, located as they are in a number of different boxes within the records of OMGUS and the State Department.

Soviet Complaints about U.S. Restitution

Heated U.S.-Soviet Exchanges

During the growing Cold War, Soviet authorities began to complain bitterly about American nonrestitution of cultural treasures despite the fact of those U.S. shipments. They constantly complained about the slowness of the Western Allied restitution process and about the rejection of many of the Soviet claims. Heated correspondence between U.S. and Soviet commanders regarding the progress and specific problems of restitution testify to the rapidly intensifying Cold War between East and West in Germany.

For example, in March 1949, the commander in chief of the Soviet Forces of Occupation, Marshal Vasilii Sokolovskii, sent an angry letter to the U.S. commander in chief, Gen. Lucius D. Clay. Sokolovskii described what he termed "an intolerable situation . . . with regard to the restitution of Soviet property." He alleged that although "almost three years have elapsed since . . . the agreements on restitution, . . . the fact is that work has actually not begun." He suggested that American authorities were "endeavoring to effectively disrupt the return of Soviet property looted by the Hitlerites." Alleging "deliberate spoilage or theft," he affirmed, by such actions "American authorities are causing material damage to the Soviet Union and ignoring the national sentiments of the Soviet people."31

General Clay addressed many of the Soviet complaints in his reply:

Of course, I find it impossible to reconcile your statement without supporting data that the return of restitution properties to your Government has not begun with the actions which we have taken to process the claims filed by your Government.

. . . In addition to the return of properties located as a result of the investigation of claims submitted by your Government we have also returned a number of paintings for which no claims were filed. We believed this action on our part was a positive demonstration of our desire to fulfill our obligations to restore looted properties.

As to your comment regarding the large percentage of rejections of Soviet claims, I can say only that the Soviet claims were not prepared as carefully as were the claims filed by other nations. This matter was repeatedly called to the attention of your Restitution Mission, but little, if any, additional supporting data was furnished to support subsequent claims.32

Lack of cooperation between U.S. and Soviet authorities over restitution issues reflected much larger political issues on the agenda.

American Knowledge of Soviet Plunder

Soviet complaints appear less serious when one realizes that U.S. restitution transfers were continued even though the Americans knew about the extent of Soviet seizures from German museums, libraries, and archives. The Allied Control Council in Germany never agreed to a principle of "restitution in kind" or "compensatory restitution," but Soviet authorities followed their own principles. Even in 1946, Soviet representatives in Germany quite openly admitted the extent of their seizures and, cynically describing German cultural valuables as "war trophies," refused to submit a list of those they had taken to the USSR.33 American authorities had many lists but chose never to make them public. Indeed, U.S. data about the Soviet cultural plunder in Germany was much more extensive than previously acknowledged, according to reports that surfaced recently in the National Archives. For example, in 1947 OMGUS authorities in Germany obtained and sent to Washington extensive inventories describing the cultural treasures shipped to Moscow. One report detailed "Russian Removals from the Islamic Department of the Former Prussian State Museum." Another noted: "Flakturm-am-Zoo and the Pergamon were completely emptied of the considerable material they contained in June and July just before the arrival of American and British forces in Berlin." Appended was a note that "the Russians took from the Dresden museums everything except German 19th century paintings and a few second rate other things and plaster casts."34

The data available to American authorities have not been published since, although they corroborate data released in Moscow over the past decade and other details published recently in the West.35 Not prepared for a confrontation with Soviet authorities over Soviet cultural seizures, American authorities chose to remain silent on that issue, although they did refuse "compensatory restitution" or "restitution in kind" to Belgium and other countries when it was requested. Apparently by the same token, however, there was little U.S. publicity about American restitution to the USSR, to the extent that even those associated with the U.S. restitution program, when queried recently, had "no recollection" of U.S. shipments to the USSR.36 In a context of the growing Cold War, the U.S. restitution had apparently not been publicized at the time in either the West or the USSR.

Cases of U.S. Non-Restitution

The U.S. transfer documents and inventories now available in the newly published CD-ROM should help counter the criticism that many cultural treasures from Soviet lands found in Germany were not returned to the USSR. It should also counter the impression that many Soviet cultural treasures found by the Americans were taken to the United States.

War Booty

Yes, there were examples of U.S. wartime or postwar seizures of booty against military regulations. One of the most notorious cases, namely the Quedlinburg Church treasures from Germany looted by an American soldier from Texas, curiously brought no government prosecution, and the heirs sold the trophies back to Germany in 1991 for a "finder's fee" of nearly three million dollars (after costly legal proceedings in the United States).37

In contrast, however, the example of the thirty-one icons seized by U.S. Customs in Texas shows that American authorities were trying to counter the problem of war booty. The return of the prehistoric artifacts found in the American Museum of Natural History in New York provides another example of the attention American museums were paying to the provenance of postwar acquisitions. Many other examples of war trophies seized in America and returned to their country and institution of origin can be documented.

The Baltic Exception

In fairness, we should recognize that U.S. authorities did not restitute several categories of cultural materials in the immediate postwar period. For example, treasures from the Baltic States were not returned because the United States did not recognize the annexation of those countries by the USSR. Justification for nonrestitution in other Baltic cases involved the legal argument that their owners had resettled abroad. That was, for example, the argument for the disposition of the so-called "Schwarzhäupter treasure," consisting of "85 pieces of ornamental silver of varying age and importance" that belonged to the Riga Blackheads, a commercial fraternity in Latvia. Restitution custody was granted on the basis of a claim from their successors then in Western Germany.38

Private Émigré Claims

A number of plundered materials were turned over to other émigrés from Soviet lands who remained in exile in the West. According to a 1948 Washington directive, U.S. authorities were "to avoid restitution to the USSR of property claimed independently by a non-national or a refugee national of the claimant government."39 Some of these transfers are now coming under closer scrutiny, as American authorities in some cases may well have erred in favor of those who were able to arrange their sanctuary abroad.

Russian attention recently has focused on the still inadequately explained fate of the revered icon of the Tikhvin Madonna. Removed by the Nazis from a monastery in Tikhvin and then taken from Pskov to Riga and used during the war for religious (and Nazi propagandistic) purposes, it was reportedly taken to Bavaria under the escort of Russian Orthodox Bishop John (Ion) of Riga. The Tikhvin Madonna was one of the specific complaints mentioned in Marshal Zorin's letter to General Clay. American restitution authorities first permitted Bishop John to use the icon for services in his church in Bavaria, where it was spotted by Soviet agents. Finally they to permitted him to take it with him to the United States in 1949, under the pretext that the icon he possessed was "not the same icon as claimed by the Soviet authorities but an imitation copied by a monastery monk near the town of Riga"—a reproduction of little value. As it has turned out, this was one matter about which the Soviets had good reason for complaint, because what is undoubtedly the original Tikhvin Madonna has recently been identified in an Orthodox church in Chicago in the custody of Bishop John's adopted son.40

Another highly disputed U.S. postwar cultural transfer was the collection of Dürer drawings from the former Lubomirski Museum in Lviv, nationalized following the Soviet annexation of western Ukraine in 1939–1940; they were seized by a personal emissary of Hitler in 1941.41 Following long-secret negotiations after the war, American restitution authorities in the State Department transferred the collection to Prince Georg Lubomirski, who claimed the drawings with supporting documentation that the terms of his family's donation had been abrogated when Soviet authorities abolished the Lubomirski Museum and nationalized the Polish collections in 1939–1940. During negotiations with U.S. authorities, Lubomirski promised the drawings to the National Gallery of Art, but he later quite legally sold the Dürer drawings at auction, resulting in their dispersal to various museums in Great Britain and the United States. At the time of the Washington Conference on Holocaust-Era Assets (December 1998), a formal claim was filed by the Stefanyk Library of the Academy of Sciences of Ukraine in Lviv for Dürer's "Male Nude" now in the National Gallery. Several recent journalistic accounts have tapped many sources and raised conflicting issues. Recently, the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa was considering (on moral grounds) turning their Dürer drawing over to Poland, but the U.S. Department of State presented a convincing opinion that the postwar "restitution" of the collection to Prince Lubomirski was justified, that the museums now holding the drawings acquired them in good faith, and that restitution to Ukraine or Poland should not be required.42 A well-documented case study is still needed, especially if and when any legal claims are filed in court.

"Redistribution" of Jewish Collections

Another controversial issue involves significant quantities of allegedly heirless Judaica and Hebraica from Soviet collections that were also not returned to the USSR and other countries in Eastern Europe as a major exception to the generally successful American policy of "restitution to the country of provenance." Because of the Nazi annihilation of Jewish communities in Eastern Europe, the lack of openly acknowledged successor Jewish institutions, and the wartime flight of many European Jews across the Atlantic and to Palestine, Western Jewish organizations very actively lobbied for the "redistribution" of Jewish cultural treasures. Of particular importance in this regard were the large collections of Judaica and Hebraica from Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania, and Latvia, including many priceless manuscripts, that had been shipped to Frankfurt by the ERR and other Nazi agencies for the Institute for the Study of the Jewish Question and its branch in nearby Hungen. Most of these ended up after the war in Offenbach. Offenbach and also Wiesbaden took in a large amount of ritual silver, numerous Torah scrolls, and other important Jewish treasures, many of which were also turned over to Jewish relief organizations for distribution to surviving Jewish communities and refugees from liberated concentration camps in the West.

Jewish Cultural Reconstruction (JCR) by 1948 became the official agency "for distribution in perpetuation of the Jewish cultural heritage."43 By 1952, over half a million Jewish books went to JCR, with at least 150,000 books sent to the United States for distribution to many different libraries, including the Library of Congress. Some went to other countries, and many more went to Jerusalem, where they have ended up in the Yad Vashem and the National and University Library in Jerusalem. Reportedly in the redistribution process, identification of provenance and appropriate restitution left much to be desired.44

As a prime example of errors in the process (not related to JCR), OMGUS files preserve a list of five crates of Hebrew manuscripts with identified provenance in different European collections, including some from Belarus, Ukraine, and the Baltic countries, that were removed illegally from Offenbach, sent to Jerusalem, and never returned or distributed to the countries of provenance, despite protests from U.S. authorities. A 1947 U.S. Army memorandum notes, "The material referred to is known to contain identifiable restitutable matter of great value, including a number of items belonging to Russian museums and libraries."45 Despite American knowledge of the irregularities, all of the manuscripts remained in Jerusalem.

Jewish collections from Lithuania could have also fallen under the prohibition of restitution to the Baltic countries that had been annexed to the Soviet Union, but Jewish cultural property was in any case handled separately. One of the largest, best known, but still complicated cases is that of the well-known Jewish [Yiddisher] Research Institute (YIVO) from Vilnius (prewar Polish Wilno, earlier Russian Vilna). At the beginning of the war, YIVO leaders who had escaped to the United States reincorporated the institute as a legal entity in New York City, thus setting legal grounds for transfer of its prewar holdings to the U.S. An estimated seventy-seven thousand books from YIVO were shipped to New York. Many of the YIVO materials were identified in Offenbach by an American YIVO devotée, Lucy Dawidowicz, who had studied in Vilnius before the war and was caught up in the postwar drama of locating and salvaging what remained in the West from the Vilnius Jewish community.46

With the recent high-level attention to "Holocaust-era assets," a more thorough study of the "restitution" and "redistribution" of Jewish property after the war is still needed. The subject was investigated by the U.S. Presidential Commission on Holocaust-Era Assets, but unfortunately their report gives few details and little documentation about their findings and does not deal with the specific East European issues.47

Today, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, many Jewish communities of Eastern Europe are reestablishing themselves and trying to identify their cultural heritage. Jewish cultural organizations are being revived and want to reclaim their legacy. Major state libraries are trying to protect the multiethnic cultural heritage of their nations, and Hebraica collections are at last coming out of hiding and being identified. There is rising resentment against Western Jewish leaders for preventing restitution of cultural treasures to the countries of origin and dispersing European Jewish treasures to different parts of the world with many sent across the seas to America or Israel.48 Such resentment may be tempered by the realization of the bitter repression of Jewish studies in the USSR and Eastern Europe during the postwar Soviet period. Besides, today many Jewish cultural treasures, books, and archives from other countries that were transferred to the USSR after the war still remain hidden or not subject to restitution from Soviet successor states. In most cases they were initially seized by the Nazis from Holocaust victims, but they have not yet been publicly described or identified in terms of provenance. As of December 2001 a new project to describe trophy Jewish cultural property is getting started in Russia, in cooperation with an American Jewish foundation.49

U.S. Intelligence Seizures and the "Smolensk Archive"

A final category of materials that was not returned to the USSR included documents of interest to American intelligence agencies. As one agent explained in the field, "We were directed by Washington to avoid restitution to the USSR of certain products considered as being of strategic importance."50 In the context of the burgeoning Cold War and the de facto political division between Eastern and Western Europe, Russian archival materials and technical publications that might have potential military or security significance were accordingly exempted from the American commitment to restitution. In addition, American intelligence was also looking for "information the Germans had on the Communist set-up in Russia" and "information on the organization, personnel, activities, and tactics of the Soviet system [and] the NKVD."51 This explains why at least 5,957 items of Russian archival and other printed materials from the OAD were turned over to the U.S. Army Intelligence units (G-2).52

Among the still-contested archival hostages are the files from the Smolensk Communist Party Archive that were removed from Offenbach and are currently held in the U.S. National Archives. They have already served their purpose as a training ground for American Sovietology, after the Nazis had confiscated them for the ERR anti-Bolshevik research center in Silesia.53 Many Russians still claim that the entire archive was taken to the United States, but now we know that Soviet authorities found five freight car loads from that same Smolensk Party Archive in Silesia in 1945 and returned them to Smolensk. Knowledge about that retrieval, however, was repressed in the Soviet Union until the archives were opened in 1991.54 But now on both sides of the Atlantic the "Smolensk Archive" has become a symbol for the international politics of restitution. Recently in the Russian Duma, America's retention of the "Smolensk Archive" was used by Russian legislators to justify their nonrestitution of their own captured archives. Despite such examples, there is good reason to believe that the cultural treasures not returned to the USSR by the United States are the exceptions, not the general rule.

Soviet Distribution of Cultural Treasures Returned

Another major concern that has arisen since the collapse of the USSR is that many of the cultural treasures returned by the United States did not reach their intended destinations in the USSR. The intensification of the Cold War and the extent of Soviet cultural plunder from Germany and Eastern Europe obviously did not leave Soviet authorities disposed to advertise the American restitution program. Another problem was the chaotic Soviet handling of restitution and trophy shipments. While some book shipments came to the suburban Leningrad distribution center in Pushkin (Tsarskoe Selo), other library receipts were being handled by the Moscow-based Gosfond. Both of these centers were simultaneously distributing trophy books and other cultural treasures plundered from Germany, cultural treasures from other European countries earlier plundered by the Nazis, and cultural treasures of Soviet provenance that Soviet authorities themselves had retrieved in the West. Often those three categories of materials were intermingled with the U.S.-restituted cultural property.

One prominent example concerns Nazi-looted twelfth-century mosaics and frescoes from the Cathedral of Saint Michael of the Golden Domes in Kyiv in Ukraine. The frescoes had been removed before the cathedral was dynamited in 1936 as part of Stalin's "urban-renewal" campaign. They were looted by the Nazis in 1943, taken first to Cracow and then to the Castle of Höchstädt. The artworks were among the materials returned from the Munich Collecting Point after the war, but only half of them were returned to Kyiv. Others have been recently located in the Hermitage and in Novgorod. Since Ukrainian independence, the church has been rebuilt, and Ukrainians have been pleading for the return of the art. The case was even raised in a UNESCO committee dealing with displaced cultural treasures. Finally in February 2001, as a political "gesture of goodwill," four fragments of the frescoes were returned to Kyiv from the Hermitage. But an "exchange" gift from Ukraine to Russia was expected, and the returned frescoes still needed extensive restoration.55

The difficulty of documenting postwar transfers and their appropriate distribution to the repository of origin in Russia or other former Soviet republics remains a problem for many museums and libraries. Although the postwar records are incomplete, a few recently opened secret files in Moscow contain some important documents about incoming Soviet shipments (including trophy shipments) from Germany and the subsequent distribution of U.S.-restituted cultural property. While remaining documentation is fragmentary, transfer documents bearing signatures from officials at museums in different parts of the USSR, including Ukraine, have been located for at least some of the cultural property received from U.S. restitution authorities.56

Of particular note, at the beginning of November 1947, eighteen freight-train wagons of cultural treasures restituted from the U.S. Occupation Zone of Germany were dispatched to the USSR from the Soviet cultural transfer center (Derutra) near Berlin. Presumably these would have comprised the materials received from the U.S. 1946 and 1947 Munich transfers (nos. 7–11 [Munich nos. 2–5], and possibly also the October 1947 transfer from Wiesbaden). Of these, eight wagons were sent directly to Kyiv and two wagons to Minsk, in addition to four to Novgorod and four wagons plus an additional flatcar for bronze statues (undoubtedly from the Neptune Fountain) that were directed to suburban Leningrad. Official representatives from the Russian, Belarusian, and Ukrainian republics had been brought to Berlin to verify the shipments. Because a full inventory at that point would have involved opening and inspecting the contents of each of the several thousand crates, they bonded each crate and wagon, after making a list of the crates to be included, before dispatching them to their destinations in the USSR. They noted that at least one thousand crates had been opened and some were damaged. Lists attached to their signed acts of attestation indicated the items with U.S. property-card registration numbers that were shipped to each destination.57

Presumably the Soviet officers accepting delivery in Munich received a copy of the official acts of transfer with inventories and property-card numbers. They were supposed to have inspected the outgoing contents of individual crates in Munich, but according to American reports, the Soviet officers present were not well-qualified museum specialists, and even if they may not have wanted readily to accept the often-vague American provenance attributions (frequently based on Nazi lists), they did not have the means to check. Given all the transfers and distribution problems, it would be quite understandable if some items were not identified correctly and distributed to their repositories of origin.

So far, the Soviet copies of the American transfer documents and the accompanying U.S. inventories of the cultural restitution transfers have not been located in Russian archives, except for the ones from Washington found by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Presumably they would be held within the records of the Soviet Military Administration in Germany (SVAG), most of the nonmilitary portions of which are housed in the State Archive of the Russian Federation (GA RF). Although the SVAG property-related records are still classified, the GA RF director, Sergei V. Mironenko, ordered a thorough search for the Soviet copies of these documents in connection with the new U.S. National Archives CD-ROM publication.58 As of the end of 2001, neither archivists in GA RF nor specialists in the Ministry of Culture have been able to locate them. The search continues.

During the Soviet era, U.S. restitution may have been officially denied in the USSR to the extent that related documentation may have been taken out of circulation. But today we live in a new century, so we can only hope that the official Soviet copies of the U.S. transfer documents and inventories will turn up and that the American restitution efforts can be better understood. Unfortunately, even ten years after the collapse of the USSR and over fifty years since the end of the war, many related files of the Soviet receiving side in the restitution process have either not been located in their entirety or remain closed to the public. The new CD-ROM publication of the copies from the U.S. National Archives may at least provide further incentive for research and will at least make available more of the hitherto-missing documentation.

* * *

Too many cultural treasures still remain displaced as a result of World War II, and many still remain unidentified. More research lies ahead, especially on specific problematic cases. We can only hope that further collaborative investigation with specialists from Russia, Ukraine, and other former Soviet republics, and more open access to documentation remaining in Russia, could help overcome the persisting Cold War attitudes surrounding displaced cultural treasures and restitution issues.

Patricia Kennedy Grimsted is research associate at the Ukrainian Research Institute at Harvard University and is a leading authority on archives of the former Soviet Union and Soviet successor states. She has written widely on World War II displaced cultural treasures, including Trophies of War and Empire: The Archival Legacy of Ukraine, World War II, and the International Politics of Restitution (Harvard University Press, 2001).

Notes

This essay is condensed from my more extensive study, "Documenting U.S. Cultural Restitution to the USSR, 1945 - 1949," published as an introduction to the CD-ROM edition by the National Archives and Records Administration: U.S. Restitution of Nazi-Looted Cultural Treasures to the USSR, 1945–1949: Facsimile Documents from the National Archives of the United States, with a foreword by Michael J. Kurtz (2001). More detailed discussion and documentation on many of points will be found there; facsimile documents included will be cited below only with reference to that edition. An initial version of that publication was presented at the conference "Mapping Europe: The Fate of Looted Cultural Valuables in the Third Millennium," held in Moscow on April 10–11, 2000, at the All-Russian State Library for Foreign Literature—VGBIL (Vserossiiskaia gosudarstvennaia biblioteka inostrannykh literatury imena M. I. Rudomino). See the report, photographs, and my remarks at www.libfl.ru/restitution/conf .

I am particularly grateful to the National Archives for assuming the costs and labor of reproduction of the documents I located with the assistance of NARA archivists and the editorial work on those editions. That study in turn draws on chapter 6 in my book, Trophies of War and Empire: The Archival Heritage of Ukraine, World War II, and the International Politics of Restitution (2001), but includes many new findings. A full bibliography of my publications regarding displaced cultural treasures (some with hot links to the full texts) is now available electonically at https://socialhistory.org/en/russia-archives-and-restitution/bibliography .

1 For a most readable account of Nazi looting and American restitution see Lynn Nicholas, The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe's Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War (1994); now also available in a Russian translation: Pokhishchenie Evropa: Sud'ba kul'turnykh tsennostei v gody natsizma (2001). See also The Spoils of War: World War II and Its Aftermath: The Loss, Reappearance, and Recovery of Cultural Property, ed. Elizabeth Simpson (1997). Regarding U.S. restitution policy, see Michael Kurtz, Nazi Contraband: American Policy on the Return of the European Cultural Treasures, 1945-1955 (1985), and his updated analysis in The Spoils of War, pp. 113–116.

2 See Konstantin Akinsha and Grigorii Kozlov (with Sylvia Hochfield), Beautiful Loot: The Soviet Plunder of Europe's Art Treasures (1995); revelations about the trophy art first appeared in a series of articles by the same authors in ARTnews in 1991. See also the revelations of Pavel Knyshevskii with the texts of still-classified documents in Dobycha: Tainy germanskikh reparatsii (1994), and the review by Mark Deich, "Dobycha—V adres Komiteta po delam iskusstv postupilo iz pobezhdennoi Germanii svyshe 1 milliona 208 tysiach muzeinykh tsennostei," Moskovskie novosti, 50 (Oct. 23-30, 1994): 18.

3 Regarding the books and archives, see Grimsted, Trophies of War and Empire, chapters 7 and 8. See also my earlier articles, "Displaced Archives and Restitution Problems on the Eastern Front from World War II and its Aftermath," Contemporary European History 6 (1997): 27–74; "'Trophy' Archives and Non-Restitution: Russia's Cultural 'Cold War' with the European Community," Problems of Post-Communism 45:3 (May/June 1998): 3– 16; and "Twice Plundered or Twice Saved?: Russia's 'Trophy' Archives and the Loot of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt," Holocaust and Genocide Studies 15 (Fall 2001): 191–244.

4 Quoted from the preamble to the law adopted in April 1998. The full text appears as "O kul'turnykh tsennostiakh, peremeshchennykh v Soiuz SSR v resul'tate Vtoroi mirovoi voiny i nakhodiashchikhsia na territorii Rossiiskoi Federatsii" (Apr. 15, 1998-64-FZ), in Sobranie zakonodatel'stva RF, 1998, 16 (Apr. 20), statute 1879. An English translation (along with the original Russian text) is available electronically at http://docproj.loyola.edu .

5 Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly, Opinion No. 193 (1996)—"On Russia's request for membership of the Council of Europe," adopted Jan. 25, 1996, which Russia was obliged to sign as a condition of admittance.

6 See Grimsted, Trophies of War and Empire, especially chap. 10. The Constitutional Court decision is printed in Sobranie zakonodatel'stva RF, 1999, 30 (Aug. 26), statute 3989. The text of the law as now amended (signed May 25, 2000-No. 70-FZ) appears in Sobranie zakonodatels'stva RF, 2000, no. 22 (May 29), statute 2259. The Russian texts of all these documents appear electronically at www.libfl.ru/restitution/law/index.html .

7 Regarding the new descriptive developments in Russia, with citations to relevant texts, see Grimsted, "Russia's Trophy Archives."

8 Aleksandr A. Surikov, addressing the Council of the Federation, quoted in Soviet Federatsii Federal'nogo Sobraniia, Zasedanie deviatoe, Biulleten', 1 (17 July 1996): 59.

9 Nikolai Gubenko, interview with the radio station "Echo of Moscow" (Apr. 22, 1997), "Luchshie interv'iu," p. 10 of 12. See also Gubenko's defensive presentation about the nationalization law in Washington Conference on Holocaust-Era Assets November 30–December 3, 1998: Proceedings, ed. J. D. Bindenagel et al. (1999), pp. 513–518, available electronically at www.state.gov/regions/eur/holocaust/heac.html.

10 The initial version presented in Moscow comprised documentation from eighteen transfers (1945–1947), but since then I documented an additional one that took place in Washington, DC, in August 1959.

11 The official U.S. Army list, "Restituted Russian Property," and covering memorandum from Richard F. Howard, deputy chief for cultural restitution (MFA&A) (Sept. 20, 1948) were first published in Grimsted (with Hennadii Boriak), Dolia skarbiv Ukraïns'koï kul'tury pid chas Druhoï svitovoï viiny: Vynyshchennia arkhiviv, bibliotek, muzeïv (1991), pp. 117–119. Facsimiles from the Records of U.S. Occupation Headquarters, World War II (OMGUS), Record Group (RG) 260, National Archives at College Park, MD (NACP) are included in the Grimsted CD-ROM.

12 Initially published in the press, a facsimile appears in Wolfgang Eichwede and Ulrike Hartung, eds., "Betr: Sicherstellung": NS-Kunstraub in der Sowjetunion (1998), plate XXXVI. In that volume, see the article by Gabriele Freitag, "Die Restitution von NS-Beutegut nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg" (pp. 170 - 208), which provides an excellent survey of U.S. restitution to the USSR.

13 Their operation and difficulties were well described by Nicholas, Rape of Europa, although Nicholas does not mention the restitution to the USSR.

14 A receipt for this shipment, signed by Lt. Col. Constantin Piartzany [sic], and a four-page list of box numbers for the 333 crates, is reproduced as Transfer #1 in the Grimsted CD-ROM. As explained in my CD-ROM "Introduction," most probably these were the collections of local newspapers and archival materials removed from Novgorod under supervision of German archivist Wolfgang Mommsen.

15 The act of transfer, with a twelve-page inventory, of archives and museum exhibits totaling 1,160 crates, is reproduced as Transfer #2 in the Grimsted CD-ROM.

16 See Transfer #3 in the Grimsted CD-ROM. According to my interview with a librarian in Smolensk, only a few looted books returned there twenty years later, with no indication of their wartime and postwar migration.

17 See Craig Smyth, Repatriation of Art from the Collecting Point in Munich after World War II (1988). In addition to the records of the Munich Collecting Point within the OMGUS Property Division records (AHC), other remaining records are held in the German Federal Archives in Koblenz (BAK—Bundesarchiv-Koblenz), as part of record group B 323—Treuhandverwaltung für Kulturgut (TVK). A newly available typescript finding aid greatly improves access. See the brief description by Anja Heuss, Kunst- und Kulturgutraub: Eine vergleichende Studie zu Besatzungspolitik der Nationalsozialisten in Frankreich und der Sowjetunion (2000), pp. 16 - 22.

See also the series "Photographs of the Restitution of Art and Other Activities at the Munich Central Collecting Point," 260-MCCP, in the NARA still pictures unit; many of the photos come from an album prepared by Smyth. Other photographs by the official photographer at Munich, Johannes Felbermeyer, are held by the Getty Center for the History of Art and Humanities, Los Angeles (www.getty.edu ).

18 Copies of the "Property Cards—Art" (many with photographs) are among the records of the U.S. Central Collecting Points, some in more than one copy, as part of the OMGUS records (RG 260), Records of the Property Division, most of them within the Ardelia Hall Collection (AHC), NACP. Many more photographs and negatives are held in the Still Pictures unit. Complete microfilm copies of the negatives linked to the property cards from the Munich CCP are now held (on temporary loan) at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, where an electronic finding aid is in preparation. Details about these resources are provided in the excellent new AAM Guide to Provenance Research, by Nancy Yeide, Konstantin Akinsha, and Amy L. Walsh (2001), especially pp. 55–105. Another copy of the property cards and photographs from the Munich and Wiesbaden CCPs remain today in Koblenz (BAK), B 323.

19 The master set of inventories by city and museum, "Verzeichnis der Treuhandverwaltung von Kulturgut München bekanntgewordenen Restitutionen von 1945 bis 1962," USSR A–Z, remain today with the Munich CCP files, B 323/578. Other detailed inventories, such as those for cultural property from Kyiv museums, remain in B 323/498; related ERR inventories are in B 323/495.

20 More examples are given in the Grimsted CD-ROM. Recently, in an effort to help better identify Nazi-plundered cultural treasures from the USSR and counter Russian denials of U.S. postwar restitution, the East European Research Center (Forschungsstelle Osteuropa) at the University of Bremen prepared a German-language CD-ROM database covering items returned to the Soviet Union, on the basis of the collection of "Property Cards—Art" in Koblenz. See Wolfgang Eichwede and Ulrike Hartung, eds., "Property Cards Art, Claims und Shipments auf CD-ROM: Amerikanische Rückführungen sowjetischer Kulturgüter an die UdSSR nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg"—Die CD der Arbeitsstelle "Verbleib der im zweiten Weltkrieg aus der Sowjetunion verlagerten Kulturgüter" (1996).

Photocopies of the "Property Cards—Art" from the records of the Munich Collecting Point (in BAK, B 323) were presented at the 1994 UNESCO-sponsored conference in Chernihiv. See H. Boriak, "Bremens'kyi proekt 'Dolia kul'turnykh tsinnostei, vyvezenykh z SRSR v roky Druhoï svitovoï viiny' (FRN)," in Materialy natsional'noho seminaru "Problemu povernennia natsional'no-kul'turnykh pam'iatok, vtrachenykh abo peremishchenykh pid chas Druhoï svitovoï viiny." Chernihiv, beresen' 1994, ed. O. K. Fedoruk, H. V. Boriak, S. I. Kot et al. (Kyiv, 1996; Povernennia kul'turnoho nadbannia Ukraïny: Problemy, zavdannia, perspektyvy, 6), pp. 251–260.

21 See the four-page inventory of the components of the Neptune Fountain in the new Grimsted CD-ROM (transfer 11 [Munich #5]). Some supporting documents are found in BAK B 323/500, and TsDAVO, 3676/1/149, fols. 256–257. See the report by Karin Jeltsch, "Der Raub des Neptunbrunnens aus Schloss Peterhof," in "Betr: Sicherstellung," pp. 67–74. See also www.peterhof.org/fount/fount17_2.html .

22 In addition to the records of the Wiesbaden Collecting Point in the OMGUS records (RG 260, AHC), see also the photographic series, "Photographs of Activities at the Wiesbaden Central Collecting Point," 260-WLA, WLB, and WLC, with a fragmentary German-language caption list in 260-WLX, NACP, Still Pictures.

23 The most detailed account of operations at OAD was prepared by one of the U.S. MFA&A officers involved with postwar restitution in Germany, Leslie I. Poste, The Development of U.S. Protection of Libraries and Archives in Europe during World War II (1964), pp. 258–301, with a chart of out-shipments by country, pp. 299–300. See also Poste, "Books Go Home from the Wars," Library Journal 73 (Dec. 1, 1948): 1699–1704. A brief account appears in an online exhibit at the web site of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum: www.ushmm.org/information/exhibitions/online-exhibitions/special-focus/offenbach-archival-depot/establishment-and-operation . See also F. J. Hoogewoud, "The Nazi Looting of Books and Its American 'Antithesis': Selected Pictures from the Offenbach Archival Depot's Photographic History and Its Supplement," Studia Rosenthaliana 26: (1992): 158 - 192, which reproduces selected photographs from the albums illustrating OAD operations (held in NACP, Still Pictures, RG 260— PHOAD). See also the remarks of the first director, Col. Seymour J. Pomrenze, "Offenbach Reminiscences and the Restitutions to the Netherlands," in The Return of Looted Collections (1946–1996). An Unfinished Chapter: Proceedings of an International Symposium to mark the 50th Anniversary of the Return of Dutch Collections from Germany, ed. F. J. Hoogewoud, E. P. Kwaardgras et al. (1997), pp. 10–18.

24 This figure for shipments to the USSR is cited by Poste, U.S. Protection of Libraries and Archives, pp. 298–300, which corresponds to the figures found in the OAD records I examined in boxes 66 and 250–262, Property Division, AHC, RG 260, NACP, but does not include transfers 15 and 16.

25 Given the importance of these albums for tracing the fate of library collections, the sections covering library stamps from former Soviet lands are reproduced in their entirety in the Grimsted CD-ROM.

Six original albums entitled "Photographs of Library Markings from Looted Books, Made by the Offenbach Archival Depot," are preserved in series 260-LM, NACP. Album II (partially duplicated in albums IV and V), but actually marked "Vol. I Eastern," covers Eastern Europe, with successive sections for "Czecho-Slovakia, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Kovno (mostly Jewish), Latvia, Poland, Russland, White Russland [Belarus], Wilno, Ukraine, and Yugoslavia." Another copy of "Volume I Eastern" is found in box 779, Property Division, AHC, RG 260, NACP. Col. Seymour Pomrenze kindly showed me his personal copy. Copies of the original albums with photographs of bookplates (ex libris), organized by country of provenance, are also retained (series 260-XL, NACP), but none of them cover Soviet collections.

26 Documentation about the books discovered in the University of Heidelberg and shipped to the Soviet embassy in Bonn in October 1962 is in BAK, B 323/497. That transfer is not counted among the nineteen U.S. transfers since it took place later under German auspices.

27 The petition is reproduced in the Grimsted CD-ROM. Dated Sept. 14, 1954, it is signed by the Very Reverend Alexander Chernay, Pastor, St. Vladimir's Church, Missionary for the Southwestern States, the Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church. Related documents are found in box 7, AHC, General Records of the Department of State, RG 59, NACP. I am grateful to Konstantin Akinsha for calling my attention to this file. The photographs of the icons are now missing from the file in NARA.

28 The act of transfer on May 31, 1957, was executed by the head of the consulate division of the embassy of the USSR in the USA and Archbishop Dionisii, acting exarchate of the Moscow Patriarch in the United States. Related documents with photographs are now preserved in the Archive of Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation (AVP RF), fond 192/37(por no. 21)/213, fols. 50-52ff. Nikolai I. Nikandrov of the Ministry of Culture RF kindly showed me copies held by his office.

29 Russian labels on individual artifacts undoubtedly led to the identification, pictured with the documents for Transfer #19 on the Grimsted CD-ROM. I am grateful to Elena Belevich, deputy director of the Historico-Documentary Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, for locating the relevant documentation in AVP RF.

30 Those transfers do not include others that were not handled by the MFA&A section of OMGUS, those that were transferred to Russian émigrés abroad, or those that were later executed by the West German government. Details are provided in the Grimsted "Introduction" to the CD-ROM. This explains why the Grimsted figure of nineteen is lower than higher figures often cited by Bremen specialists.

31 Vasilii Sokolovskii to Lucius D. Clay, Mar. 5, 1949, reproduced in the Grimsted CD-ROM.

32 Clay to Sokolovskii, Mar. 10, 1949, reproduced in the Grimsted CD-ROM. Also in the same file is a four-page memorandum of Maj. Henry D. Anastasas to M. H. McCord, Mar. 8, 1949, in preparation for Clay's response to Sokolovskii.

33 See Grigorii Kozlov (with Konstantin Akinsha), "Diplomatic Debate on Cultural Restitution Matters 1945–1946," electronic version in English and Russian in the April 2000 VGBIL conference proceedings at www.libfl.ru/restitution/conf/kozlov_e.html and www.libfl.ru/restitution/conf/kozlov_r.html .

34 See, for example, the secret report on "Soviet Removals of Cultural Materials," June 7, 1947, addressed to the Adjutant General at the War Department from Lt. Col. G. H. Garde, with twenty-three enclosures, most of them detailed reports and inventories of specific Soviet removals, box 129, Adjutant General decimal files, 1947, RG 260, NACP.

35 See especially, Akinsha and Kozlov, Beautiful Loot. Lynn Nicholas' book was completed before all of the new details were released, but she also described the Soviet plunder in Berlin and elsewhere in East Germany, Rape of Europa, pp. 362–367, from other sources. See the list of shipments (based on documents collected by Akinsha and Kozlov) published by Waldemar Ritter, "The Soviet Spoils Commissions: On the Removal of Works of Art from German Museums and Collections," International Journal of Cultural Property 7: 2 (1998): 446–455, and Klaus Goldmann, "The Treasure of the Berlin State Museums and Its Allied Capture: Remarks and Questions," in ibid, pp. 308–441.

36 That was the response of former directors of the postwar U.S. Collecting Points when they were queried in a session on the American restitution program at the 1995 Symposium in New York. See Grimsted, "Captured Archives and Restitution Problems on the Eastern Front," in The Spoils of War, p. 246.

37 See the contributions from the special session on the Quedlinburg treasures in The Spoils of War, pp. 148–158. The jeweled cover of the ninth-century Samuhel Gospels and several other treasures looted by the American GI from Texas are pictured in ibid., p. 23. See also the account by Siegfried Kogelfranz and Willi A. Korte, Quedlinburg—Texas und zurück: Schwarzhandel mit geraubter Kunst (1994).

38 See the transfer receipt and inventory of forty-nine items (Sept. 7, 1951), box 105, Property Division, AHC, Restitution and Custody Receipts, RG 260, NACP.

39 "Soviet Restitution Claims," box 23, Records of the Property Division, Russia, RG 260, NACP.

40 Anastasas to McCord, Mar. 8, 1949, box 24, Property Division, USSR confidential, RG 260, NACP. Considerable correspondence regarding the Tikhvin icon remains in U.S. restitution records. The existence of the original in Chicago was confirmed to me by a Church representative in July 2000, although I have not seen it myself; it has also been confirmed by the Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation. See Ol'ga Vasil'eva, "Netlennyi plennyi obraz," Novoe vremia, 1995, no. 17, pp. 34–35.

41 See the catalog of the collection by Mieczyslaw Gebarowicz and Hans Tietze, Albrecht Dürers zeichnungen im Lubomirskimuseum in Lemberg (1929), presented in a folio edition with reproductions of all twenty-four drawings. H. S. Reitlinger, "An Unknown Collection of Durer Drawings," Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs (London), March 1927, pp. 153–155, includes plates reproducing nine of the drawings and brief descriptions of the rest.

42 See the most recent article by Konstantin Akinsha and Sylvia Hochfield, "Who Owns the Lubomirski Dürers?" ARTnews 100:9 (October 2001): 158 - 163; Akinsha and State Department officials kindly updated me on subsequent developments. Among earlier accounts, see the excellent coverage by Michael Dobbs, "Stolen Beauty," Washington Post Magazine, Mar. 21, 1999, pp. 12–18, 29, which concludes, in line with the opinion of the director of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, and the U.S. Department of State, that the Ukrainian claim probably would not stand up in court. Martin Bailey, "Hitler, the Prince and the Dürers," in The Art Newspaper (London) 6 (April 1995): 1–2, suggests the drawings rightfully belong to Lviv and that American restitution authorities probably had no right to return them to Prince Georg Lubomirski. That conclusion was repeated in more outspoken terms in the Lviv newspaper, Vysokii zamok, 1999, no. 1, p. 1. See also Bailey's follow-up article on the 1998 claim by the Stefanyk Library in Lviv, "Growing unease over Lubomirski Dürers," The Art Newspaper 93 (June 1999): 3.

43 See the secret reports and memorandums regarding Offenbach holdings (two undated in November, one in December, and the other dated Dec. 14, 1948), and the later confidential report (received March 1949) from OMGUS Chief of Staff, Civil Affairs Division, signed Hays," box 607, Records of the Executive Office, AG, General Correspondence, decimal file, RG 260, NACP.

44 Documentation about this program is found among the OAD records, boxes 66, 254, and 256, and scattered in other OMGUS files, Property Division, AHC, OAD, RG 260, NACP. It has recently come to light, for example, that many identified books from the Baltic countries (excluded from U.S. restitution) went to Jerusalem. See U.S. Presidential Commission on Holocaust-Era Assets, Plunder and Restitution: The U.S. and Holocaust Victims' Assets (2000), chapter 6, for discussion of JCR.

45 Library markings and provenance are indicated in many cases for boxes 2 and 5, but no details are provided for the "107 Hebrew manuscripts" in box no. 1 or the "110 Hebrew manuscripts" in box no. 4. In addition to the Baltic countries, libraries of several Jewish communities in Germany (including Frankfurt and Karlsruhe among other private owners) are given, and three have library marks from Italy, including one from the Rabbinical College in Florence, and several from Poland. The covering memorandum, "Material wrongfully sent from Offenbach Archival Depot and presently at Jerusalem" (May 27, 1947) (unsigned cc with signature line for Col. L. Wilkinson), box 66 (and box 240), Property Division, General Records, AHC, OAD, RG 260, NACP. The case is mentioned in Plunder and Restitution, p. SR-199.

46 Regarding the identification and recovery of the YIVO collections from Offenbach during the period February–June 1947, see the moving chapter in the memoirs of Lucy Dawidowicz, From That Place and Time: A Memoir, 1938–1947 (1989), pp. 312–326. See also David E. Fishman, Embers Plucked from the Fire: The Rescue of Jewish Cultural Treasures in Vilna (1996; with parallel text in Hebrew).

47 See Plunder and Restitution.

48 This problem was particularly apparent in the 2000 Vilnius Forum on Holocaust-Era Cultural Assets, where representatives of many European Jewish museums and other institutions found themselves at odds with the Israeli claim that all "heirless" Jewish cultural property should go to Israel. See the proceedings at www.vilniusforum.lt/proceedings/index.htm .

49 The "Research Project for Art and Archives," sponsored by Ronald S. Lauder and Edgar M. Brofman, is specifically intended to describe cultural treasures of Holocaust victims. The text of the agreement signed with the Ministry of Culture in Moscow (4 December 2001) is at the website www.comartrecovery.org , under "accomplishments—Russia." I am grateful to Konstantin Akinsha for updating me about the project.

50 "Soviet Restitution Claims," box 23, Records of the Property Division, Russia, RG 260, NACP.

51 "Matters of Interest to Liaison Agent," GMDS, Camp Ritchie, MD, unsigned [n.d.], copy, AGAR-S, no. 1393 (GMDS 5:1 folder 1), National Archives Collection of Foreign Records Seized, RG 242, NACP.

52 Poste cites the total figure in the table of transfers to G-2 from Offenbach, Poste, U.S. Protection, p. 299, but references to additional transfers are found in OAD records in RG 260, NACP. Many actual seizures of Soviet books and archival materials by U.S. intelligence agents have not been adequately documented, although in addition to the Smolensk Archive, several other groups of records of Russian provenance remain in the National Archives.

53 See Grimsted, The Odyssey of the "Smolensk Archive": Plundered Communist Records for the Service of Anti-Communism, Carl Beck Papers in Russian & East European Studies, no. 1201 (1995). A separate updated article on this subject is planned.

54 Regarding the Soviet retrieval in 1945, see Valerii N. Shepelev, "Sud'ba 'Smolenskogo arkhiva,'" Izvestiia TsK KPSS, 1991, no. 5, pp. 135–138. Shepelev includes reports of the Red Army political unit that found the Smolensk records, from RGASPI (earlier RTsKhIDNI), 17/125/308, fols. 11–12. See Grimsted, Odyssey of the Smolensk Archive, pp. 44–48. See also V. N. Shepelev, "Novye fakty o sud'be dokumentov 'Smolenskogo arkhiva' (po materialam RTsKhIDNI)," Problemy zarubezhnoi arkhivnoi rossiki: Sbornik statei (1997), pp. 124 - 133.

55 See Serhii Kot, "Povernennia mykhailivsktkh fresok: kul'turno-istorychnyi barter?" Polityka i kul'tura, 90 (Feb. 27–Mar. 5, 2001): 40–41. Additional inventories of these materials, including church plans, photographs, and negatives, are preserved in the Munich records in BAK, B 323/498. See Kot's most recent article with several pictures, "Mykhailivs'ki relikviï kolo zamknulosia," Politika i kul'tura, (130) (Dec. 18-24, 2001): 44–46.

56 In 1997 I was permitted to examine some files within the partially declassified series (opis' 2) of the records of the Committee on Cultural-Enlightenment Affairs of the RSFSR (Komitet po delam kul'turno-prosvetilel'skich uchrezhdenii RSFSR) (predecessor of the Ministry of Culture of the USSR), GA RF, A-534/2. For example, among U.S. shipments to the USSR in one list from June 1946 were 26 crates from the Ukrainian SSR—T. Zuev to A. A. Zhdanov (June 6, 1946), GA RF, A-534/2/10, fol. 218. Another file (GA RF, A-534/2/13), includes receipts for 40 crates for the Kerch Museum (fol. 3), 268 crates for the Historical Museum in Kyiv (fols. 9–15), and others being transferred to Feodosii in the Crimea in 1948 (Crimea was part of the RSFSR until 1954).

57 See the signed official transfer documents (with accompanying chart of corresponding U.S. property card numbers), (Sept. 6, 1947), GA RF, A-534/2/14, fols. 6–19, 27–28, 34, 39–40, and 52. For example, the act of transfer to Ukraine (fols. 6-9) has an attached list (fols. 10–19), specifying 1,127 crates of museum items from Kyiv among 2,391 crates received from the American Zone (copy, fols. 41–50). The act of transfer to Minsk has 182 items (fols. 20–21; cc. fols. 53–54). See also the inventory of paintings and icons from Novgorod and Pskov received from Germany (Jan. 27, 1948), fols. 65–113, and fols. 116–120.

The Bremen group also surveyed this problem with limited success, although the German researchers themselves had not seen the original files. See Ulrike Hartung, "Der Weg zurück: Russische Akten bestätigen die Rückführung eigener Kulturgüter aus Deutschland nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg. Probleme ihrer Erfassung," "Betr: Sicherstellung," pp. 209–221.

58 Most other sections of SVAG records have now been declassified, and a joint Russo-German project is under way to create an electronic finding aid, but records relating to property matters and trophy transfers remain closed. I appreciate the efforts of Sergei Mironeko and his GA RF colleagues to locate the documents and regret that a joint publication was not possible on their basis.