“Remember Me”: Six Samplers in the National Archives

Fall 2002, Vol. 34, No. 3

By Jennifer Davis Heaps

Martha Earl is my/ name

Hackensack is/ my station

Heaven/ is my dwelling [place]/

And Christ is my [sal/v]ation

When I [am]/ dead and in my grav/

- e and all my bones/ are rotten

For/ this you sea remem/ber me

That I are/ not forgottin/

She was born August/ 1 AD 1781

ABCDEFGHI

This arresting statement from a work of early American schoolgirl art is not meant to declare a fascination with the morbid but an acknowledgment of how fleeting life is. The above text appears on one of six fragile needlework samplers made by young girls two hundred years ago that are found among the voluminous records in the National Archives' Revolutionary War pension files.

These works of linen and silk, created as personal family treasures, became federal documents when pension claimants required to show proof of relationship to a Revolutionary War veteran submitted them to the U.S. government. Though the samplers long ago answered the questions asked by pension officials, today we ask different questions: Who made these samplers? What happened to the girls after they finished the last stitch? Because recordkeeping in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was so inconsistent, tracing sampler makers and their teachers is difficult. Using information from the samplers and the pension files in which they appear, we can learn a little about these artifacts and their makers. Supplementing any extant birth and marriage data with census schedules and published local histories allows us to sketch out at least a brief outline of these girls' lives. Seeing their samplers takes the viewer to a time vastly different from our own.1

The Needlework Tradition

Samplers are pieces of fabric worked to practice various embroidery stitches and motifs and to demonstrate mastery of these. In early America, they were not made for hobby or as a way to pass leisure time. Touching on a variety of styles and designs, samplers have their roots in medieval Europe, and English women carried this tradition to the New World early in the seventeenth century. The earliest known surviving sampler from colonial America is an undated piece by Mayflower passenger Myles Standish's daughter Loara.2 Other surviving examples from the 1600s are variations on the same general design theme of flowers in a band (horizontal) pattern with sets of alphabets and numbers occasionally present. In the eighteenth century, sampler designs and formats began to vary, as did the places where needlework was being taught and handed down to new generations of girls.

Education was not widely available to most people in the colonial period. Girls in families that could afford it received instruction in various female accomplishments like needlework and painting. Girls usually learned fancy needlework in schools run by women who advertised a familiarity with a variety of subjects.3 Other girls received private lessons. Educational opportunity spread somewhat after the American Revolution, but even then, education came at some price, and not everyone could afford to pay it. Girls who attended any kind of school or who received private tutoring likely came from at least what we would consider a middle-class family in economic and social status. After the Revolution, girls started to study more of the academic subjects boys studied, but if nothing else, most girls would be taught some basic level of sewing as a requirement and necessity in preparing them to run a household.

Samplers are the most tangible evidence of female education at the time, although very few of the instructors have been identified.4 The alphabets and numbers, depictions of flowers or various symbols, and religiously inspired verses or other virtuous expressions employed in samplers attested to a girl's knowledge of these matters, her sense of refinement, and her skill in using a needle and thread.5 Many samplers, ranging from the most sophisticated to the most naïve, were framed and proudly displayed in the home. While samplers are extant from the seventeenth century into the late nineteenth century, the heyday of sampler making in America existed until about 1825, with the finest work often dated before 1785.6 The stitching of samplers thrived in Boston and elsewhere in New England, with fine work made in other cities such as Philadelphia.7 The few samplers in the National Archives pension files are similar to the variety of samplers found in many public and private collections.

The Revolutionary War Pension Files

The pension files, numbering around eighty thousand, consist of applications the federal government received in response to pension legislation enacted in various laws between 1818 and 1878. The pension's amount depended on the serviceman's military rank and length of service. Widows of men who provided service received the right to apply for pensions beginning in 1836. If the veteran had not received a pension, the widow had to prove her late husband had served in the war. In order to be eligible for benefits, widows or surviving adult children also had to provide proof of their relationship to the former serviceman. This was difficult in some cases because the recording of vital statistics information was not uniform. The record of a marriage was often in the custody of the clergyman who performed the ceremony rather than with a colony or state office. Even in instances where a marriage may have been recorded, the record may have been subsequently destroyed.

Many widows received assistance with their claims from men in their region who acted as their agents. These middlemen navigated the sometimes lengthy and difficult process of applying for pensions. Agents often sought additional evidence for claimants and forwarded it to the Office of the Commissioner of Pensions in Washington, D.C.8

Because of the difficulty in producing official records, the federal government allowed the sworn testimony of one or two witnesses to the marriage. Even this, however, could be a problem when none of the witnesses were living at the time the widow or other family member applied for a pension. In addition, many people did not hold on to military discharge papers and other records that did not seem to serve any purpose past their original use. As a result, widows occasionally would produce "unofficial" family records documenting the marriage and, sometimes, the birth of children from the marriage. These submissions took the form of manuscript and printed family registers (or "family records" as they were called), manuscript and printed birth and baptismal certificates of the Pennsylvania Germans (frakturs), and to a lesser degree, embroidered needlework samplers.9 The National Archives discovered these while microfilming the Revolutionary War pension files in the 1970s.

The six samplers may be divided into two groups: three that record birth information for the samplers' makers and three that provide birth information for their entire nuclear families. The first group consists of three very different samplers reflecting a range of ages of the makers and geographic area of origin. The second group comprises three family register samplers, two of which were made in Berkshire County, Massachusetts, and the third either there or in eastern New York. Members of this latter group all exhibit a similar format with variations on the family register theme, and are all unsigned and undated.

Without any context, these artifacts may be regarded as mere curiosities—fragments of old cloth decorated with stitches. Or they may be appreciated for their obvious age and old - fashioned quality, hinting at what we often perceive to have been simpler times. In The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich studied several artifacts related to cloth and its production in early America. In the course of examining museum objects with family histories associated with them, she noticed how the stories of objects became distorted over time, with added romanticism and the conflict of history carefully omitted. She concluded that people "make history not only in the work they do and the choices they make, but in the things they choose to remember."10

One of the benefits of having samplers submitted as government evidence is the context provided by the files in which they appear. While extensive family histories would be interesting to have, the bureaucratic nature of the files' correspondence and depositions lets the samplers exist without embellishment. The government accepted these as legal proof and decided whether pensions would be awarded accordingly.

So what do the samplers in the pension files represent, and who made them? Despite their obvious pictorial differences, the samplers are all similar in their general methods of production. Each maker had to sit still for lengths at a time, beginning with the task of pushing a silk thread into the eye of a needle. This, in turn, she used to puncture an angular-shaped linen cloth over and over again with text and design, achieving a result that could be elegant (Mary Hearn) or a confusing jumble (Patsey Bonner). Girls did this work for the primary purpose of learning to become industrious housewives.

Martha Earl's Sampler, ca. 1787

Martha Earl made what is probably the earliest sampler among those in the National Archives. Although it is undated, this sampler likely was made when Martha was about six years old, dating it to about the year 1787. Her sampler of relatively small size, with large cross-stitch letters and few graphics, bears the hallmarks of a beginner's piece of work. What gives this piece its charm despite some losses of fabric are its identification of Martha as the maker, Hackensack as her home town, her birth date, and the verse itself. Even young children were taught that life was short and to confront their own mortality, as seen in this popular verse.11

The daughter of Morris Earl and Elizabeth Terhune, Martha was born into one of the many families of Dutch descent in her community.12 Her father was a prominent figure in the town of Hackensack, New Jersey. He was a member of the Justices and Freeholders of Bergen County in the late eighteenth century and hosted some of their meetings in his home.13 He kept a tavern, and this was likely his home as well.14 Operating this business made the Earls prosperous enough that they were able to have their daughter Martha receive some education. She later stated of her sampler that it was "one that she worked when a small girl and went to school."15 She submitted the sampler to the Pension Office because it provided her date of birth, proving that her parents were married. To corroborate this, her uncle, Cornelius Terhune, stated that he was present when Martha was baptized.16 Their agent added, "I expect you are well aware that no children can be baptised in the dutch Church except the parents are legally married."17

By the time she was about twenty years old, Martha married Casparus Bertholf. They lived in New Barbados township in the Hackensack area and raised a family of several children. Her father died in 1833.18 She was still living there in 1842, a widow herself, when she submitted her sampler to assist her mother in obtaining an annual pension of $51.33 from the federal government based on her father's Revolutionary War service as a private.

Patsey Bonner's Sampler, 1792

Martha Bonner, nicknamed Patsey, submitted her sampler later in life as a widow in 1846 to prove her marriage to her husband. She made the sampler in 1792 when she was about seventeen years old, shortly before she married John McKenzie. The identity of her parents is not known. She apparently lived in Washington County, Georgia, at the time she made the sampler.19 She likely was related to George Bonner and Sherwood Bonner, who held 250-acre land warrants each in the county.20 Washington County was rural and not particularly prosperous. It is possible that Patsey learned needlework further east in a coastal area.21 According to the 1850 population census schedule, she was born in Virginia, and perhaps she learned there the skills to make her sampler "worked with a needle in letters and figures."22

Several things about Patsey's sampler are striking, beginning with its place of origin. Compared to New England and elsewhere in the North, relatively few samplers have survived from the South. Scholars have developed some theories surrounding this gap, focusing on the South's agrarian economy and its effect on education. Most of the samplers in the North were made in urban or well-settled areas that could support educating children in groups. The Southern population that could afford to educate its children generally sought private tutors instead, and these often were men, rather than women who could teach needlework along with academic subjects. Another potential factor is Southern weather. The very humid climate in many parts of the South is thought to be incompatible with the long-term survival of many samplers that may have been made but whose existence is not known.23

More intriguing about Patsey's sampler is its design. Her work appears very unstructured for a girl in her upper teens, displaying an apparent preference for the letter "w." It is unlikely that this sampler was made under the watchful eye of a demanding teacher, but not all the stitching is of a simple nature. The repeated use of letters in contrasting stitches is unusual, as is the uneven spacing of the text. The mysterious combination of letters and numbers in the middle, the wavy bands below them, the name of her brother, and the relatively monochromatic color scheme in the silk thread are other surprising touches. Shortly after she married, Patsey added the information at the bottom about her marriage and started to stitch her brother James Bonner's birth date, but she never quite completed her work.

Not surprisingly, John McKenzie had some slaves before his marriage. In 1791 or 1792, "he had two negros to run away from him when he lived in . . . Georgia and went to the Creek Indians and were lost to him entirely." For his loss, Congress compensated John with one thousand dollars.24 After Martha married John, they moved from Georgia and lived in Murray County and Carroll County, Tennessee. They had children of their own and were well known in their vicinity. When John died in 1842, the former captain had been a pensioner for nine years. His death notice noted his Revolutionary War service and lamented his passing as one of "those who achieved our glorious Independence."25 The Pension Office awarded his widow increasingly generous pensions in 1846, 1849, and 1851, the last in the amount of six hundred dollars annually. In her later years, Martha lived with her son James M. McKenzie and his family.26 The town of McKenzie, Tennessee, in Carroll County is named for the family.

Mary Hearn's Sampler, 1793

Mary Hearn's engaging, sophisticated 1793 sampler is the earliest known example of work done under the tutelage of an unknown instructor in Nantucket, Massachusetts. Needlework scholars have identified other examples of similar Quaker style on Nantucket Island, but none as early as Mary's sampler. Typical of these Nantucket samplers are "fat little trees," such as those along the bottom border of Mary's sampler.27 The teacher may have been Phebe Folger, who taught in the first Quaker school established on Nantucket.28 Mary's handiwork displays more intricate stitches than some previously known samplers of this kind. Her teacher must have been exacting to get such a beautiful result from a ten-year-old.

Born in Dutchess County, New York, Mary was the only child of Daniel and Elizabeth Hearn. A wagon conductor during the war with an apparent rank of captain, Daniel participated in several battles, was wounded, and was present at the hanging of Major Andre.29 He and Elizabeth were married in Newburgh, New York, by an army chaplain. Mary never knew her father, as he died traveling to Virginia when she was an infant. Poignantly, she and her mother recalled in Daniel's pension file a letter he had written to Elizabeth years before while on a trip, reminding her almost prophetically to "take good care of his Baby."30 Sometime after Daniel died, Elizabeth and Mary moved to Nantucket, where Elizabeth had relatives. Elizabeth's mother was distantly related to Benjamin Franklin, as they shared a common ancestor in Peter Folger.31

It seems likely that Mary was raised as a Quaker. She alludes to this in a letter she wrote included in the pension file by declaring that "I never was baptised."32 She probably mentioned this by way of explaining that she could not produce a baptismal record proving her age. Settled by Quakers in the seventeenth century, Nantucket still had a strong Quaker population in the 1790s. Still, there was no Quaker school until 1797, four years after Mary made her sampler. As a young widow, Elizabeth would have needed a way to support herself and her baby daughter. Perhaps she did some teaching herself before the Quaker school was established. Could she be the mysterious instructor of the Nantucket samplers? Or, perhaps, at least an influence on Phebe Folger, who may have been the real teacher who designed this motif? It is probably not possible to determine that for certain, but because Mary's sampler predates the existence of the school it is tempting to consider the possibility.

A letter in the file written by Mary implies that she and her mother, Elizabeth, left Nantucket just before the War of 1812. Mary then taught school in Rhode Island for a time before moving further west and settling in Marathon, Cortland County, New York. She eventually married Peter Fralick.33 Records at the Nantucket Historical Association indicate, however, that Mary had a previous marriage to Joseph Elkins, who was killed aboard a privateer in 1820. They had a daughter, Phebe.34

Like some grown women who displayed childhood samplers, Mary later decided to disguise her age by altering her birth date. She eventually had to account for this to the Pension Office by saying in 1847 that "the figures which appear altered, appeared somewhat obliterated, and deponent caused said figures to be reworked and that said figures are the same they originally were except the Stile of the work and the color of the silk."35 The Pension Office awarded Mary's mother, Elizabeth, a pension of $276.66 a year until her death in December 1847.

Harriet Bacon's Sampler, ca. 1804–1805

In the late eighteenth century, family identity edged out community as the focus of personal association, giving rise to the great popularity of family records in both ink and needlework formats.36 Harriet Bacon never finished her family record sampler, made about 1804 or 1805, although she left plenty of room for her eventual remaining siblings. The fourth of nine children born to Samuel Bacon and Anna Guiteau, Harriet apparently never married, and her life is difficult to trace.37

Her parents lived in Lanesboro, near Pittsfield in northern Berkshire County, Massachusetts, for many years after her father's Revolutionary War service as a private. They eventually moved to Trenton, Oneida County, New York, where Anna's brother, Luther Guiteau, practiced medicine and was Samuel's attending physician at his death in 1840.38 Samuel had been a Revolutionary War pensioner for several years before he died. Unfortunately, the Bacons are not recorded in the annals of published histories of Trenton. This may reflect another move for Anna after Samuel died or the lack of descendants in the community over time to ensure their place in the local history.

Harriet submitted her sampler in 1841 on her mother's behalf because the written family record on which it was originally based was long since lost. She "worked" her sampler "when she was either 10 or 11 years of age."39 Despite the sampler's unfinished state, something compelled Harriet or her parents to keep it. Had she become ill while working on it, never to catch up? We can only guess. The sampler, however, helped ensure the successful outcome of Anna's claim for a pension of $23.33 a year because it included the date of her marriage to Samuel.

Laura Goodale's Sampler, ca. 1809

Laura Goodale, daughter of Chester Goodale and Asenath Cook, made what is the most visually appealing of the three genealogical samplers. Her choice of colors for the silk thread enhance what might otherwise be a plain though well-executed piece of needlework. Laura's sampler, created around 1809, lists the birth and marriage dates of her parents as well as their children. Her family lived in several places in Berkshire County, Massachusetts. Chester Goodale was active in community life in West Stockbridge, having joined the Baptist Society in 1794 and helping to chart a Masonic Lodge in 1803.40

Later, when he was living in Egremont, Massachusetts, he applied for and was granted a pension for his service as a private in the Connecticut militia. He had no documentary proof of any kind. He had "no record of his age. . . . He never received a written discharge. He has no documentary evidence of his services nor does he know of any person living by whom he can prove them."41 The Pension Office deemed credible his assertions of military service, however, and he received a pension of fifty dollars annually. Chester was asked to supply his age, a statement of service, the battles in which he was engaged, his residence upon entering the service, the type of evidence to support his statement, and whether any papers of support were weak in form or authentication. After he died in 1835, his widow, Asenath, began the process of applying for additional installments of pensions under subsequent acts of Congress.

Among the later documents submitted to substantiate the continuation of payments was Laura's sampler. As she testified at age forty-seven in 1840, When about sixteen years of age and while my father was living I worked the sampler of needle work now enclosed and annexed to this deposition, being a record of our family, that the facts as they now appear upon the same were related to me by my father and mother, and so far as they can be known to me, with certainty they are correct. And those of which I cannot be supposed to know of my own knowledge, I have the fullest reason to believe correct. My mother is still living unmarried and dependent upon her children for support.42

Laura conscientiously had added the birth of another sibling outside the lines of her original design sometime after she first completed the sampler. The local justice of the peace, Robert F. Barnard, further testified that "the annexed sampler of needle work was delivered me by [Laura Hadley] . . . after being cut from a frame which appeared to have been long used in the family."43 The file does not tell us whether attempts to locate other records were made before surrendering the sampler, but the pension was awarded.

Like Harriet Bacon, Laura used a strawberry and vine border. Because the Bacon and Goodale families lived a reasonable distance apart and the strawberry border was popular in many areas, we cannot conclude that the samplers were made at the same school. However, Laura used the abbreviation "viz." for the Latin videlicet, meaning "namely." This appearance on the sampler before the list of children indicates influence or instruction from someone reasonably well educated, even if Laura was not directly familiar with that usage.

Seventy years later, personnel of the Pension Office, by then known as the Bureau of Pensions, inserted notes into Chester Goodale's file expressing concern about the sampler. A transcription of the sampler was made with an accompanying note that "the above . . . is taken from a sampler which has this day been taken from the claim and locked up in the Revolutionary Section of the Record Div[ision]." A similar note reiterated this and indicated that a "sampler [was] removed from this case and locked up for safekeeping."44 Concern for the sampler's well being probably arose because the bureau was receiving increasing numbers of genealogical requests from the public inquiring about the Revolutionary War service of ancestors. By the time Laura Hadley's sampler was removed in 1910, the bureau had already answered several inquiries for information about Chester Goodale. Staff undoubtedly believed that repeated use of his file could result in either damage to the sampler or theft, since sampler collecting had become popular by the early twentieth century.45

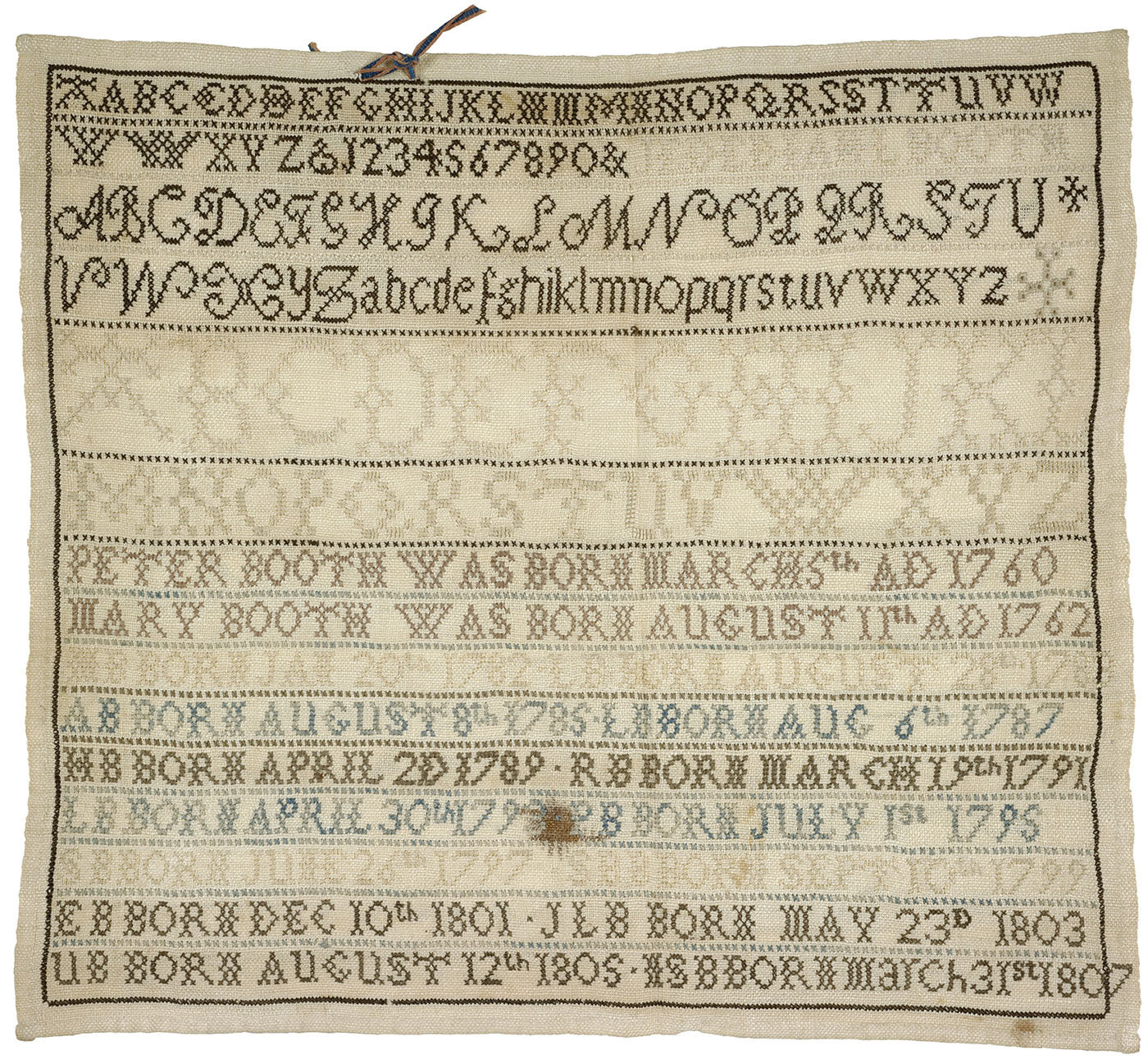

Huldah Booth's Sampler, ca. 1818

The crisply executed sampler documenting the births of the children of Peter Booth and Mary Leonard did not prove compelling enough evidence for the application of some of their children in the 1850s. Veteran Peter Booth had applied for a pension under the act of 1818, was rejected, and died later that year. His widow applied for a pension after passage of the act of 1836 and was granted $56.66 annually but died not long afterward in December 1838.46

Several years later, her children decided to try to continue to receive payments and in 1848 submitted the sampler made by Peter and Mary's daughter Huldah as proof of their relationship to the couple. Huldah testified that she knew of "no record of their marriage now in existence but knows that the sampler hereto annexed is an old original sampler worked by this deponent more than thirty years since" and that the dates recorded on it were "truly copied from an old family record."47 Unfortunately, the sampler did not include the date of Peter and Mary's marriage, and the children could only estimate the year.

A few years after receipt of the sampler, the Pension Office reexamined the Booth case and not only questioned whether the Peter Booth whose family applied for a pension was the same person as the man who served in the Revolution, but the marriage was called into question, as well. Pension officials determined that "the requirements of this office with regard to the proof of the date of the marriage have not been complied with."48 Peter and Mary's son Jedediah Booth tried several times to have this determination overturned, but the records do not indicate that he had any success. Apparently, the discrepancies had been overlooked for the widow during her lifetime but not for the surviving adult children after 1851.

Remember Me

In the 1840s, as John McKenzie and other elderly Revolutionary War veterans were passing away, so was needlework in female education. By the start of the Civil War, sampler making had become a lost practice. Changes in education for girls in particular and a world view challenged by industrialization pushed this decorative needlework to the margin of life. Nevertheless, transcending time, many samplers have carried on admirably in their role as coveted artifacts.

Samplers and other needlework are among the textile collections of numerous art museums and historical societies. They also have a strong following among private collectors. When the very best examples enter the marketplace, they command incredible prices at auction. The highest price ever paid for a piece of needlework was in 1996 at Sotheby's when the hammer fell at $1,157,000 for Hannah Otis's circa 1750 chimneypiece.49 Sampler collectors have made quite an impact on the appreciation of this schoolgirl art. Some of the most diligent collectors have contributed handsomely to needlework research. Thousands of humbler and undocumented samplers are available at antique shops and shows at any given time, waiting for new collectors to join the hunt.

When signed, these artifacts are often the only record of a girl's life. Vital statistics were not recorded as routinely or as meticulously as they are in our own time. The domestic roles most women played did not lend themselves to documentation in the public record. Fortunately, a few pieces of their girlhood accomplishments are part of the vast archives of the United States because they were used as evidence in documenting federal claims. To a discerning collector, none of these particular examples have the right combination of rarity, condition, charm, and fine workmanship that would make them especially sought-for treasures on the open market. But they do have individually and as a group what archivists call intrinsic value.50 As federal records, these samplers provide a valuable dimension to the national experience because they are also cultural icons of their time.

We have no idea whether the girls who stitched these samplers enjoyed making them, but we know they saved them, even when not completed like Patsey Bonner's and Harriet Bacon's. They framed them, like Laura Goodale's. And they saw their worth as legal proof by sending them to their federal government. What's more, the government understood their value as proof and reciprocated by using them to make decisions on granting pensions.

"When this you see remember me" was a common refrain used in samplers. The widespread popularity of this verse is shown in the geographical and chronological breadth of its occurrence. The makers hoped that their efforts would be appreciated beyond their own mortal existence because girls made samplers at a time when they could not assume that their whole lives lay ahead of them. Undoubtedly, many girls were taught that others would continue to see the evidence of their skill after they had died.

Martha Earl was but a little girl when she stitched her reference to her eventual death. We cannot truly remember someone like Martha, whom we never knew, so removed from our time and place. But when we study her sampler with its misspellings and backward letters, we can appreciate the humble efforts she made as a small child with silk and linen. In turn, this evidence of her life invites us to imagine and wonder about Martha, others like her, and the vanished world in which they lived.

Details about Samplers Found in the Revolutionary War Pension Files

Jennifer Davis Heaps is a member of the Policy and Communications Staff and has worked in several archival program units at the National Archives and Records Administration.

Notes

The author wishes to thank NARA colleagues Ed Stokes, Zinnia Cho, Jeffery Hartley, J. Calvin Jefferson, Michael Meier, and Cynthia G. Fox for their assistance during the research for this article. The author also thanks her sister, Kirsten Davis Thomas, who introduced her to the world of needlework scholarship. Textile and needlework scholar Susan Burrows Swan provided helpful comments on a draft of this article. Elizabeth Oldham of the Nantucket Historical Association provided additional genealogical information for Mary Hearn.

1 Three works were indispensable to the study of the samplers in the National Archives. Susan Burrows Swan, Plain and Fancy: American Women and Their Needlework, 1650–1850 (rev. ed. 1995), provides an excellent overview of plain household stitching and its importance in a girl's education in chapter 1, "Plain Sewing, Plain Housewives." For a thorough study of samplers, including family records, made as part of formal education, see Betty Ring, Girlhood Embroidery: American Samplers & Pictorial Needlework, 1650–1850, 2 vols. (1993). See also Gloria Seaman Allen, Family Record: Genealogical Watercolors and Needlework (1989), for many examples of family records in needlework.

2 Swan, Plain and Fancy, p. 52.

3 Ring, Girlhood Embroidery, pp. xvii–xviii.

4 Ibid., p. xix.

5 Although making samplers was mostly the province of white Christian girls, this activity was so pervasive that it touched on others in the larger society. There is evidence that some African American girls learned to make samplers. Schools that accepted free blacks existed in Newport, RI, and New York briefly in the eighteenth century. Needlework was likely part of their lessons. (Glee Krueger, New England Samplers to 1840 [1978], p. 2). Kimberly Smith Ivey describes a charity school for black children in Williamsburg, Virginia, 1760–1774, that taught girls knitting, sewing, and other skills (In the Neatest Manner: The Making of the Virginia Sampler Tradition [1997], p. 65). Ivey notes that no known needlework survives from that school or for any African American girl in Virginia. However, Ivey discovered an 1807 Norfolk ad for a runaway slave that mentions she knew how to sew, knit, and mark by a sampler. Betty Ring describes a sampler, dated 1832, embroidered with the name of the St. James First African P E Church School in Baltimore. (Ring, Girlhood Embroidery, p. 512).

In Samplers and Samplermakers: An American Schoolgirl Art 1700–1850 ([1991], pp. 149–153), Mary Jaene Edmonds tells the story of an 1828 sampler made by an American Indian girl at the Cherokee Mission School in Dwight, AR. There also are a relatively few extant examples of samplers made by Jewish girls, as cited in Anne Sebba's Samplers: Five Centuries of a Gentle Craft (1979), p. 111. These were sometimes distinguished by their inclusion of Hebrew letters and Jewish religious motifs. Finally, some boys made samplers. Glee Krueger speculates that these may have been completed to occupy boys at home or "dame" schools when girls completed their needlework. (Krueger, New England Samplers, p. 18).

6 Swan, Plain and Fancy, p. 6.

7 Ring, Girlhood Embroidery, pp. 12–14.

8 The Office of the Commissioner of Pensions went through several name changes. Throughout this article it is referred to as the Pension Office.

9 These number about 120 items in all. The author is completing a study of the English-language ink and watercolor family records that compose the majority of this total.

10 Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth (2001), p. 414.

11 Different versions of this verse appear on samplers created in various geographic areas and time periods. It had incredible staying power. See for example, Glee Krueger's A Gallery of Samplers: The Theodore H. Kapnek Collection (1978), which illustrates a 1743 example from Charleston, SC (p. 23, figure 16), 1748 Boston (p. 24, fig. 18), 1828 Marietta, PA (p. 70, fig. 101), and ca. 1840 New Hanover, PA (p. 84, fig. 120). Krueger's New England Samplers to 1840 (1978) illustrates another example dated 1793 from Springfield, MA (no page, fig. 28). In the South, Kimberly Smith Ivey's In the Neatest Manner (1997) shows a 1761 sampler from Isle of Wight County, VA (p. 56, fig. 74), and in the Midwest, Sue Studebaker's Ohio Samplers: Schoolgirl Embroideries, 1803–1850 (1988) shows an 1837 sampler of Pike Township, Clark County (no page, fig. 30).

12 W. Woodford Clayton, History of Bergen and Passaic Counties, New Jersey, with Biographical Sketches of Many of its Pioneers and Prominent Men (1882), p. 254.

13 Minutes of the Justices and Freeholders of Bergen County, New Jersey, 1715 - 1795, from the Original in the County Clerk's Office (1924), pp. 187, 227.

14 Morris Earl's position as a taverner is noted in Adrian C. Leiby's The United Churches of Hackensack and Schraalenburgh, New Jersey, 1686 - 1822 (1976), p. 268.

15 Deposition of Martha Bertholf, May 2, 1842; pension file of Morris Earl, New Jersey, W849; Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files (National Archives Microfilm Publication M804), roll 885; Records of the Veterans Administration, Record Group 15.

16 Deposition of Cornelius Terhune, May 2, 1842, ibid.

17 Letter of David Pye to James L. Edwards, May 20, 1842, ibid.

18 Martha's husband's name appears variously spelled as Casparus, Cadparus, and Jasper, the latter in Morris Earl's pension file. The baptisms of their children are captured in Herbert Steward Ackerman and Arthur J. Goff, comps., First Hackensack Reformed Church Records, 1801 - 1886 (n.d., 2nd ed.). Morris Earl mentioned several family members in his will. Martha is possibly referred to as Patty here. The will also mentions "Negro—Peter," who is likely the slave enumerated in Morris Earl's household in the 1830 federal population census. The will is cited in Bergen County Will Abstracts, Book D.1, p. 328, transcribed by a New Jersey chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

19 Deposition of Martha McKenzie, Oct. 3, 1843; pension file of John McKenzie, North Carolina/South Carolina/Virginia, W1049; M804, roll 1690.

20 Mary Bondurant Warren and Jack Moreland Jones, comps., Washington County, Georgia Land Warrants, 1784–1787 (1992), p. 12.

21 Ella Mitchell, History of Washington County (1924; reprint, 2000), pp. 11–12.

22 Deposition of Martha McKenzie, Oct. 26, 1846; pension file of John McKenzie, M804, roll 1690.

23 Ring, Girlhood Embroidery, pp. 532–538. Kimberly Smith Ivey's In the Neatest Manner is an expansive exhibit catalog focusing on Virginia samplers. Ivey's work demonstrates that there were, at least in Virginia, many young girls making samplers as part of their education (see pp. 49–52).

24 J.A.N. Murray to J. L. Edwards, n.d., pension file of John McKenzie, M804, roll 1690.

25 A copy of John McKenzie's November 11, 1842, death notice appears in his pension file.

26 Martha is enumerated with her son and his family in the 1850 federal population census.

27 For examples, see Ring, Girlhood Embroidery, p. 149, fig. 165; p. 150, figs. 166 and 167; and Charles H. Carpenter, Jr. and Mary Grace Carpenter, The Decorative Arts and Crafts of Nantucket (1987), p. 95, fig. 72; p. 96, figs. 73–74; and plates 33 and 34.

28 Ring, Girlhood Embroidery, pp. 148–149.

29 Deposition of Mary Fralick, Feb. 12, 1846, pension file of Daniel Hearn, Massachusetts, W17064; M804, roll 1242.

30 Deposition of Elizabeth Hearn, Feb. 12, 1846, ibid.

31 Elizabeth Oldham, Nantucket Historical Association, to the author, July 5, 2002 (email).

32 Mary Fralick to Wheeler H. Clark, n.d., ibid.

33 Ibid. Elizabeth was enumerated in the 1810 federal population census in Nantucket. She does not appear in published indexes for the federal population censuses of Nantucket taken in 1790 or 1800.

34 Elizabeth Oldham to the author, July 5, 2002.

35 Deposition of Mary Fralick, Apr. 5, 1847, pension file of Daniel Hearn, M804, roll 1242.

36 Allen, Family Record, p. 1.

37 Charles J. Palmer, History of the Town of Lanesborough, Massachusetts, 1741–1905, Part I (n.d.), p. 84.

38 John F. Seymour, Centennial Address, Delivered at Trenton, N.Y., July 4, 1876 (1877), pp. 26 - 29.

39 Deposition of Harriet Bacon, Jan. 4, 1844; pension file of Samuel Bacon, Massachusetts/New York, W20681; M804, roll 105.

40 Edna Bailey Garnett, West Stockbridge, Massachusetts 1774–1974: The History of an Indian Settlement Queensborough or Qua-Pau-Kuk (1976), pp. 65, 92.

41 Deposition of Chester Goodale, Aug. 15, 1832; pension file of Chester Goodale, Connecticut, W19522; M804, roll 1088.

42 Deposition of Laura Hadley, n.d., Ibid.

43 Deposition of Robert F. Barnard, May 25, 1840, ibid.

44 The first note is dated "Mch 7, 1910," and the second is undated; ibid. Patsey Bonner's and Mary Hearn's samplers were similarly safeguarded.

45 See Ring, Girlhood Embroidery, pp. 543–548.

46 Deposition of Jedediah L. Booth, Jan. 17, 1848; pension file of Peter Booth, Connecticut/Massachusetts, W15597; M804, roll 289.

47 Deposition of Huldah Andrews (Andrus), Jan. 17, 1848, ibid.

48 F. S. Evans, Pension Office, to Hon. H. S. Conger, House of Representatives, Mar. 8, 1851, ibid.

49 This price includes the buyer's premium. See Deborah Harding and Laura Fisher, Home Sweet Home: The House in American Folk Art (2001), p. 18. A chimneypiece is a long, horizontal landscape piece of needlework designed to be displayed over a fireplace mantel.

50 See "Intrinsic Value in Archival Material," Staff Information Paper 21, National Archives and Records Service, 1982. Intrinsic value has been defined as "the inherent worth of a document based upon factors such as age, content, usage, circumstances of creation, signature, or attached seals" (Lewis J. Bellardo and Lynn Lady Bellardo, comps., A Glossary for Archivists, Manuscripts Curators, and Records Managers [1992], p. 19)