“Any woman who is now or may hereafter be married . . .”

Women and Naturalization, ca. 1802–1940

Summer 1998, Vol. 30, No. 2 | Genealogy Notes

By Marian L. Smith

The fact that women are not equally represented among the nation's early naturalization records often surprises researchers. Those who assume naturalization practice and procedure have always been as they are today may spend valuable time searching for a nonexistent record. At the same time, many genealogists do find naturalization records for women. The resulting confusion about this subject generates a demand for clear, simple instructions by which to guide research. Unfortunately, the only rule one can apply to all U.S. naturalization records—certainly all those prior to September 1906—is that there was no rule.1

There were certain legal and social provisions, however, governing which women did and did not go to court to naturalize. In general, immigrant women have always had the right to become U.S. citizens, but not every court honored that right. Since the mid-nineteenth century, a succession of laws worked to keep certain women out of naturalization records, either by granting them derivative citizenship or barring their naturalization altogether. It is this variety of laws covering the history of women's naturalization, as well as different courts' varying interpretation of those laws, that help explain whether a naturalization record exists for any given immigrant woman.

While original U.S. nationality legislation of 1790, 1795, and 1802 limited naturalization eligibility to "free white persons," it did not limit eligibility by sex. But as early as 1804 the law began to draw distinctions regarding married women in naturalization law. Since that date, and until 1934, when a man filed a declaration of intention to become a citizen but died prior to naturalization, his widow and minor children were "considered as citizens of the United States" if they/she appeared in court and took the oath of allegiance and renunciation.2 Thus, among naturalization court records, one could find a record of a woman taking the oath, but find no corresponding declaration for her, and perhaps no petition.

Unless a woman was single or widowed, she had few reasons to naturalize prior to the twentieth century. Women, foreign-born or native, could not vote. Until the mid-nineteenth century, women typically did not hold property or appear as "persons" before the law. Under these circumstances, only widows and spinsters would be expected to seek the protections U.S. citizenship might afford. One might also remember that naturalization involved the payment of court fees. Without any tangible benefit resulting from a woman's naturalization, it is doubtful that many women or their husbands considered the fees to be money well spent.

New laws of the mid-1800s opened an era when a woman's ability to naturalize became dependent upon her marital status. The act of February 10, 1855, was designed to benefit immigrant women. Under that act, "[a]ny woman who is now or may hereafter be married to a citizen of the United States, and who might herself be lawfully naturalized, shall be deemed a citizen." Thus alien women generally became U.S. citizens by marriage to a U.S. citizen or through an alien husband's naturalization. The only women who did not derive citizenship by marriage under this law were those racially ineligible for naturalization and, since 1917, those women whose marriage to a U.S. citizen occurred suspiciously soon after her arrest for prostitution. The connection between an immigrant woman's nationality and that of her husband convinced many judges that unless the husband of an alien couple became naturalized, the wife could not become a citizen. While one will find some courts that naturalized the wives of aliens, until 1922 the courts generally held that the alien wife of an alien husband could not herself be naturalized.3

In innumerable cases under the 1855 law, an immigrant woman instantly became a U.S. citizen at the moment a judge's order naturalized her immigrant husband. If her husband naturalized prior to September 27, 1906, the woman may or may not be mentioned on the record which actually granted her citizenship. Her only proof of U.S. citizenship would be a combination of the marriage certificate and her husband's naturalization record. Prior to 1922, this provision applied to women regardless of their place of residence. Thus if a woman's husband left their home abroad to seek work in America, became a naturalized citizen, then sent for her to join him, that woman might enter the United States for the first time listed as a U.S. citizen.4

In other cases, the immigrant woman suddenly became a citizen when she and her U.S. citizen fiancé were declared "man and wife." In this case her proof of citizenship was a combination of two documents: the marriage certificate and her husband's birth record or naturalization certificate. If such an alien woman also had minor alien children, they, too, derived U.S. citizenship from the marriage. As minors, they instantly derived citizenship from the "naturalization-by-marriage" of their mother. If the marriage took place abroad, the new wife and her children could enter the United States for the first time as citizens. Again, if these events occurred prior to September 27, 1906, it is doubtful any of the children actually appear in what is, technically, their naturalization record. The lack of any record for those children's naturalization might cause some of them, after reaching the age of majority, to go to naturalization court and become citizens again.

Just as alien women gained U.S. citizenship by marriage, U.S.-born women often gained foreign nationality (and thereby lost their U.S. citizenship) by marriage to a foreigner. As the law increasingly linked women's citizenship to that of their husbands, the courts frequently found that U.S. citizen women expatriated themselves by marriage to an alien. For many years there was disagreement over whether a woman lost her U.S. citizenship simply by virtue of the marriage, or whether she had to actually leave the United States and take up residence with her husband abroad. Eventually it was decided that between 1866 and 1907 no woman lost her U.S. citizenship by marriage to an alien unless she left the United States. Yet this decision was probably of little comfort to some women who, resident in the United States since birth, had been unfairly treated as aliens since their marriages to noncitizens.5

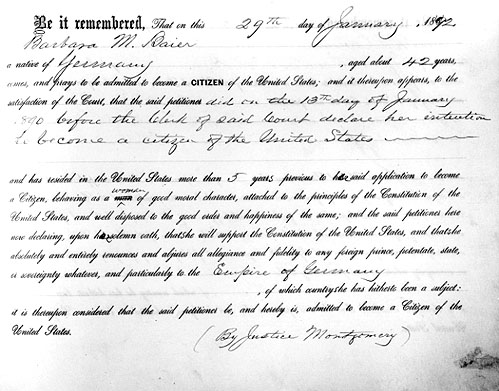

By the late nineteenth century, marital status was the primary factor determining a woman's ability to naturalize. But other factors might have influenced a judge's decision to grant or deny a woman's naturalization petition. Some judges seemed unaware of legal naturalization requirements and regularly granted citizenship to persons racially ineligible, who had not lived in the United States the requisite five years, or did not display "good moral character." It may be that these judges also granted citizenship to women regardless of their husband's nationality. Women's naturalization records dating from the 1880s and 1890s can be found, for example, among the records of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia (Record Group 21), though these records do not indicate the women's marital status.

After 1907, marriage determined a woman's nationality status completely. Under the act of March 2, 1907, all women acquired their husband's nationality upon any marriage occurring after that date. This changed nothing for immigrant women, but U.S.-born citizen women could now lose their citizenship by any marriage to any alien. Most of these women subsequently regained their U.S. citizenship when their husbands naturalized. However, those who married Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, or other men racially ineligible to naturalize forfeited their U.S. citizenship. Similarly, many former U.S. citizen women found themselves married to men who were ineligible to citizenship for some other reason or who simply refused to naturalize. Because the courts held that a husband's nationality would always determine that of the wife, a married woman could not legally file for naturalization.6

There were exceptions to the 1907 law's prohibition against the naturalization of married women. Good examples can be found in the West and upper Midwest, where individuals were still filing entries under the Homestead Act in the early twentieth century. Many women filed homestead entries, either while married to aliens or prior to marrying an immigrant. Later, when they petitioned for the citizenship necessary to obtain final deed to the property, some judges granted their petitions despite their marital status. In these cases the judges held that if the government intended to deny the women citizenship it should not have allowed them to file entries with the General Land Office. In other homestead-related cases, the granting of citizenship to women seemed less a matter of principle and more a method, adopted locally, to acquire additional property.7 Women's inability to naturalize during these years did not prevent them from trying. Many women filed declarations of intention to become citizens and may have even managed to file petitions before being denied. At least one woman's petition came before the court because she did not declare her marital status. Often women had no choice but to file at least a declaration of intent. In some states aliens could not file for divorce or other court proceedings. An alien woman seeking divorce might file the declaration simply to facilitate filing a separate suit.8 Declarations of intention and petitions filed by women should remain on file with other court naturalization records.

A few women successfully naturalized in these years, but they might have subsequently had their naturalization certificates canceled. Finnish-born Hilma Ruuth, for example, filed her declaration of intention to become a citizen in the U.S. District Court at Minneapolis, Minnesota, on December 1, 1903. In 1910 Hilma married Jaakob Esala, another Finnish immigrant, and in the same year she filed her petition for naturalization with the district court of St. Louis County, at Virginia, Minnesota. Her petition bore her married name, Hilma Esala, and the U.S. Naturalization examiner in St. Paul filed a formal objection to her petition under the 1907 law, which prohibited the naturalization of women married to aliens. The county judge overruled this objection and granted Hilma U.S. citizenship on November 19, 1910. The naturalization examiner responded by passing the case to the U.S. district attorney, who then filed suit in U.S. District Court on January 24, 1911, for cancellation of the certificate. The case was decided on July 11 at the Federal Building in Duluth, where Hilma's citizenship was canceled and she had to surrender her certificate of naturalization.9 Federal court records of certificate cancellation proceedings are, like federal court naturalization records, found in Record Group 21. Unless there is a name index to the court's records, researchers will need to know the court's specific name (i.e., U.S. District Court, U.S. Circuit Court) and location, the type of case, and case number.

The era when a woman's nationality was determined through that of her husband neared its end when this legal provision began to interfere with men's ability to naturalize. This unforeseen situation arose in and after 1918 when various states began approving an amendment to grant women suffrage (and which became the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1920). Given that women who derived citizenship through a husband's naturalization would now be able to vote, some judges refused to naturalize men whose wives did not meet eligibility requirements, including the ability to speak English. The additional examination of each applicant's wife delayed already crowded court dockets, and some men who were denied citizenship began to complain that it was unfair to let their wives' nationality interfere with their own.10

Happily, Congress was at work and on September 22, 1922, passed the Married Women's Act, also known as the Cable Act. This 1922 law finally gave each woman a nationality of her own. No marriage since that date has granted U.S. citizenship to any alien woman nor taken it from any U.S.-born women who married an alien eligible to naturalization.11 Under the new law women became eligible to naturalize on (almost) the same terms as men. The only difference concerned those women whose husbands had already naturalized. If her husband was a citizen, the wife did not need to file a declaration of intention. She could initiate naturalization proceedings with a petition alone (one-paper naturalization). A woman whose husband remained an alien had to start at the beginning, with a declaration of intention. It is important to note that women who lost citizenship by marriage and regained it under Cable Act naturalization provisions could file in any naturalization court—regardless of her residence.12

By this time, confusion over women's citizenship, and how a woman might regain U.S. citizenship, had become common. The case of Karen Marie Hosford is a good example. She was born in Denmark and immigrated to Canada, where she met and married Grant Hosford in 1911. He was a U.S. citizen, and under U.S. law Karen became a U.S. citizen through their marriage. Then Grant naturalized as a Canadian citizen in 1915, and Karen, too, thereby lost her U.S. citizenship. The couple soon migrated to the United States. After a few years Grant decided to regain his U.S. citizenship and filed a declaration of intention at his local naturalization court. Unfortunately, Grant died in 1923, not yet naturalized, and left Karen an alien widow. At that point she could petition for naturalization based on his declaration, citing the original 1804 act which gave her that right. But the 1922 act also gave her the option to file her own declaration and begin the naturalization process in her own right.13

While it appears foreign-born women did not complain about any remaining link between a woman's naturalization and her husband's, some Naturalization Bureau officials thought any remaining connection was unfair.14 Clear dissatisfaction was expressed by U.S.-born women who, in many cases, belatedly discovered they had lost their citizenship by marriage prior to September 1922 and now must petition for naturalization if they wished to regain it. After considering that other Americans who expatriated themselves by swearing allegiance to another nation during World War I needed only to take the oath of allegiance in court to restore their U.S. citizenship, U.S. Commissioner of Naturalization Raymond Crist suggested that Congress might create some similar provision for U.S.-born women:

Some women feel that a certain stigma attaches to the need of "naturalization" in the same manner as any lowly immigrant. Women of perhaps Mayflower ancestry, whose forbears fought through the Revolution, and whose family names bear honored and conspicuous places in our history, who are thoroughly American at heart, and who perhaps have never left these shores, but whose act in choosing alien husbands has caused forfeiture of American citizenship, bemoan the stipulation that such as they must sue for naturalization by the ordinary means.15

Not until 1936 did Congress comply with Crist's request, and then only for those women who lost U.S. citizenship by marriage between 1907 and 1922 and whose marriage had terminated through death or divorce. If she met this criteria she could file an application with her local naturalization court and resume her citizenship upon taking the oath of allegiance. The application was typically made on Form N-415, Application to Take Oath of Allegiance to the United States, which should be filed in separate volumes from each court's other naturalization records. Some courts, however, interfiled these documents with other petitions. In 1940 Congress allowed all women who lost citizenship by marriage between 1907 and 1922 to repatriate, or resume their citizenship, regardless of their marital status. Since then, any woman who lost U.S. citizenship in those years by marriage to any alien, even if they remained happily married, could resume her citizenship by applying and taking the oath of allegiance.

The subject of women and naturalization was often as confusing to people in the past as it is to researchers today. Not all courts upheld or strictly enforced naturalization requirements. Other misunderstandings arose when naturalization records did not change as rapidly as did naturalization law. For example, after implementation of the Cable Act in 1922, naturalization certificates continued to call for the name of the new citizen's spouse until at least 1929. This was a remnant of the days when women derived nationality from their husbands, and the name inserted on the certificate after 1922 was usually that of the wife. There were subsequently instances where unnaturalized spouses used such certificates as proof of citizenship, even using them to obtain U.S. passports from the Department of State.16

Still other misunderstandings arise today because some are unable to fathom that immigrant women may have gained U.S. citizenship by any means other than naturalization. There is a surprising number of elderly women alive today who gained U.S. citizenship by marriage to U.S. citizens prior to 1922. Too often they and their children are sent scrambling to obtain some proof of the woman's citizenship so that she might retain some benefit to which she is entitled. It was not until 1929 that women who gained citizenship through their husband's naturalization after marriage could obtain a "Certificate of Derivative Citizenship" from the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). And it was not until 1940 that INS could issue certificates to women who gained citizenship by marriage to a man already a citizen.17 While not in themselves proof of citizenship for legal purposes, proof of marriage to a U.S. citizen occurring prior to September 22, 1922, and proof of the husband's U.S. citizenship, remain as the foundation for legally documenting a foreign-born woman's citizenship.18

Marian L. Smith is the senior historian for the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, Washington, D.C. She writes and speaks about the history of the agency.

Notes

1. For information on the location of federal, state, and local court naturalization records and their availability on microfilm, see Christine Shaefer, Guide to Naturalization Records of the United States (1997). For information about various aspects of naturalization laws and procedures, see John J. Newman, American Naturalization Processes and Procedures, 1790-1985 (1985).

2. Act of March 26, 1804—Widow and Children of Declarant (§ 2168) "shall be considered as citizens of the United States, and shall be entitled to all rights and privileges as such, upon taking the oaths prescribed by law." Repealed by Basic Naturalization Act of June 29, 1906, but continued in section 4(6) of that act. Repealed 1934, but citizenship of those who previously gained citizenship under this provision remained secure. An act of February 24, 1911, allowed the wives of insane declarants to naturalize following the same procedure.

3. Act of Feb. 10, 1855 (§ 1994, rev. § 2172); see In re Rionda, 164 F 368 (1908); United States v. Cohen, 179 F 834 (1910).

4. Sidney Kansas, Citizenship of the United States of America (1936), p. 67.

5. Frederick A. Cleveland, American Citizenship as Distinguished from Alien Status (1927) pp. 65-66.

6. Ibid.; see also Rule 24(k) of the Naturalization Laws and Regulations, Feb. 15, 1917 (1917), p. 33.

7. Report of Robert A. Coleman, Chief Naturalization Examiner, St. Paul, MN, to Richard K. Campbell, Commissioner of Naturalization, Washington, DC, July 1, 1910, p. 3, entry 26, box 1698, file 457177, pt. I, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC (hereinafter RG 85, NARA).

8. Robert A. Coleman, Chief Naturalization Examiner, St. Paul, MN, to Commissioner of Naturalization, Washington, DC, Feb. 2, 1924, entry 26, box 399, file 20/2, RG 85, NARA. See also "Must be Naturalized under Married Surname of Husband," in Kansas, Citizenship of the United States of America, pp. 70-71.

9. INS C-File 154992 (including naturalization records of Hilma Esala, District Court of St. Louis County, at Virginia, MN, Nov. 19, 1910, and court decree of the U.S. Circuit Court, District of Minnesota, Fifth Division, July 25, 1911, and other correspondence).

10. Sundry correspondence relative to courts requiring wife of petitioners to attend court at final hearing, 1919-1922, entry 26, box 1475, file 3929, RG 85, NARA.

11. Until 1931, women still expatriated themselves by marriage to an alien racially ineligible to naturalize.

12. Luella Gettys, The Law of Citizenship in the United States (1936) p. 50.

13. Case of Karen Marie Hosford, entry 26, file 23/3444, RG 85, NARA.

14. Paul Armstrong, Chief Naturalization Examiner, Denver, CO, to Commissioner of Naturalization Raymond Crist, Washington, DC, June 30, 1923, entry 26, box 399, file 20/2, RG 85, NARA.

15.Annual Report of the Commission of Naturalization, 1923, p. 13.

16. Thomas Griffing, District Director of Naturalization, St. Louis, MO, to Commissioner of Naturalization, Apr. 3, 1929, entry 26, box 399, file 20/2, RG 85, NARA.

17. Nora H. Reardon, "Derivative Citizenship of the United States--the Law, Procedure, and Practice in its Determination, and in the Issuance of Documentary Evidence of Such Status." (lecture, INS Course of Study for Members of the Service) Jan. 7, 1943, pp. 14-15.

18. Naturalization Examiner's Guide, Applications for Certificates of Citizenship, Documentary and Other Evidence (INS, Nov. 1, 1964), pp. 8-20 to 8-25 (TM 8-1-70).

Certificates of Derivative Citizenship are issued only by INS, not by the courts. To apply for a certification of citizenship, submit INS Form N-600 to your local district office of the Immigration and Naturalization Service.