Racial Identity and the Case of Captain Michael Healy, USRCS, Part 3

Fall 1997, Vol. 29, No. 3

By James M. O'Toole

© 1997 by James M. O'Toole

Three years later, Captain Healy had what might be considered a second marriage—this time to a ship called the Bear. Built in Scotland as a whaler, it had been acquired by the United States in 1884 and refitted for Arctic duty. It was by far the biggest vessel the Revenue Service had in the area, two hundred feet long and reinforced with heavy steel plating that could take it confidently through the ice. With a crew of nine officers and forty men—most of whom, like their captain, spent their entire careers in the far north—it could do eight knots under sail and more than nine when its steam engines were put to use. Its first assignment had been to participate in the famous expedition to find the Greeley exploration party in Alaska, and several decades later it would go to the South Pole with Admiral Byrd. During the decade in which Michael Healy was its captain, the Bear was not merely a useful ship; it was, as the official historian of the Coast Guard has said, "a symbol for all the service represents—for steadfastness, for courage, and for constant readiness to help men and vessels in distress."(17)

For sheer romance, Healy's time in command has much to offer. The hard work of rescue and law enforcement, each episode an adventure in itself, became routine. The ship carried the mail and agents of the Treasury Department and other government agencies to the region and brought them home again. More than once the territorial governor was aboard, and suspects and witnesses in various crimes, ranging from liquor smuggling to murder, were brought down to California to face justice. The vessel aided the coast and geodetic surveys, which were engaged in basic mapping of the area, and various missions of exploration also relied on her. Most interesting of all was the Bear's role in a plan to promote the economic self-sufficiency of Alaska's natives. With the decline of seal hunting, many groups of Aleuts and Inuits had fallen on very hard times, and the introduction of alcohol by settlers from "below" had only, in the view of many observers, made matters worse. Captain Healy had noticed, however, that the tribes across the Bering Straits in Siberia were more prosperous because they had successfully turned to the herding of domesticated reindeer. Accordingly, together with Sheldon Jackson, the great Presbyterian missionary to Alaska, Healy hit on the idea of importing reindeer to the American side so the peoples there could do the same. Beginning in 1891, he shuttled back and forth between the two continents, winching the animals aboard the Bear, twenty or more at a time, and transporting them across. With only uncertain federal support for the program, the plan was never the success Healy and Jackson had hoped for, but their efforts showed a genuine concern for Alaska and its people at a time when that was rare for representatives of the United States.(18)

His work as commander of the Bear made Captain Healy, a New York newspaper said, "a good deal more distinguished . . . in the waters of the far Northwest than any president of the United States or any potentate of Europe. . . . If you should ask in the Arctic Sea, Who is the greatest man in America?' the instant answer would be, Why, Mike Healy.'" Once, an "innocent" from the effete East inquired who he was and got the succinct answer: "He's the United States." Unsolicited testimonials were regularly sent to Washington on his behalf. In 1889 more than fifty masters and owners of whaling ships praised "his long experience in Arctic navigation, his knowledge of the ice and currents, [and] his promptness of action in rendering assistance." His wife, who frequently accompanied him on his summer-long voyages, basked in the honors accorded him. When the Bear pulled into one island settlement, the Russian Orthodox missionary priest in charge of the village ordered flags flown and churchbells rung for the heroic captain. "I assure you," Mary Jane Healy confided in her diary, "it delighted me much to see so much respect paid to my husband."(19)

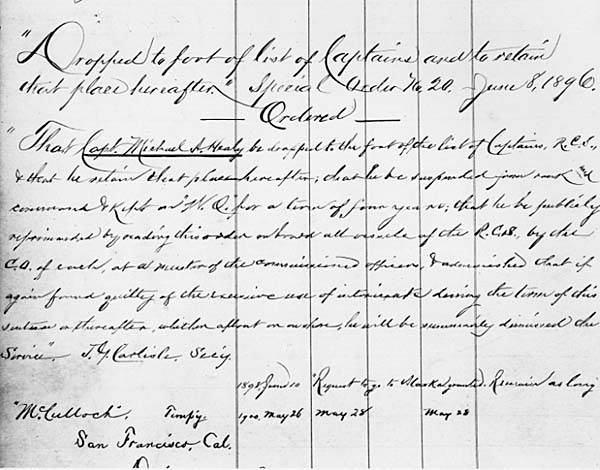

Not even two court-martial trials—the first in 1890, the second in 1896—diminished the esteem in which most people held him. The transcripts of these trials, now part of the Coast Guard records in the National Archives, show that he had always taken a no-nonsense approach to command, and this could get him into trouble. His punishment of certain members of his crew led to charges of brutality, and full investigations were ordered. On both occasions, he was accused of particularly severe forms of punishment, including "tricing" offenders. This procedure consisted of tying a man's hands behind his back and then hoisting him up by the wrists until his feet were just above the surface of the deck, leaving him there for about five minutes. Hanging in that position was very painful, and if the man succumbed to the appealing temptation to touch his feet to the deck for relief, his arms were bent further back, and the pain redoubled. This traditional form of nautical punishment was still technically permissible in the Revenue Service, though it had become rare and was soon after abandoned, in part as a result of the graphic testimony in Healy's trials. Compounding his offense, his accusers maintained, the captain had been drunk on both occasions, a charge that brought supporting protests from temperance advocates on shore, who apparently wanted to make an example of him as part of their general campaign against the use of liquor in the service. He was fully acquitted at the first trial: the whole case had been trumped up, one newspaper reported, by those who "knew nothing" about life in the Arctic and who simply wanted to besmirch the reputation of "a good and faithful officer."(20)

His second trial in 1896 did not go as well. Stories of abusive treatment of his men persisted, and this time the charges of drunkenness seemed true. On the morning of Thanksgiving Day 1895, while the Bear lay at anchor in Sausalito harbor after having just returned from its yearly Arctic cruise, Healy was "disgracefully intoxicated" and spat in the face of one of his junior officers. Worse, witnesses said, the captain had been drunk repeatedly while in command of the vessel all the previous summer and had even staggered off the dock into the water at Unalaska "to the great mortification of officers assembled at a social gathering." A sympathetic panel of Revenue Service officers had to find him guilty, and he was punished with removal from command of the Bear. Reprimanded and dropped to the bottom of the captain's list, he managed to redeem himself by rising to the top again. In 1900 he was given command of a new ship, the McCulloch, but his troubles persisted. While piloting that ship from the Aleutians back to Seattle in July of that year, he apparently succumbed to drink yet again. While intoxicated, he spoke sharply to a female civilian on board; when his men restrained him, he threatened to kill himself. Though he dried out, he had snapped, and an extended psychotic episode ensued: tied up and confined to his cabin, he managed to break the crystal on his watch and made a messy but unsuccessful attempt at slashing his wrists. Once back in port, he was placed for a time in a marine hospital, where he finally came to his senses. Though restored to the captaincy of yet another cutter, he retired from the service in the fall of 1903 and died of heart failure the following summer.(21)

Despite these sad last chapters in the story of his life, Mike Healy had a distinguished career in the Revenue Cutter Service, but his successes were possible in large measure because he was not known to be partly of African American heritage. Whenever he spoke about his work, he made it clear that he saw only two kinds of people in Alaska, "natives" and "white men," and he used the latter term to denote anyone who was not a native, including himself. So long as his ship was nearby "the Natives are . . . gentle and peaceful," he reported to a superior in Washington, "but I believe they would not hesitate to take advantage of . . . white men" in isolated camps. He repeatedly referred to white settlers as "our people," and was even able to passed this racial identity on to a subsequent generation. His teenage son Fred, who accompanied his father on a voyage in 1883, scratched his name into a rock on a remote island above the Arctic Circle, proudly telling his diary that he was the first "white boy" ever to do so.(22)

The two hot incidents with which this essay began indicate how successfully Captain Healy had established his identity as something other than an African American, how successfully he had evaded the "one-drop" rule. In those confrontations with his disrespectful and mutinous subordinates came a significant racial test. Can we really suppose that these two ordinary sailors were restraining themselves, calling him a "God damned Irishman" when another word would have been the more hurtful and insulting, had they only known to use it? Is it not more likely that, given the chance, they would have called him a "black son of a bitch" rather than simply a "son of a bitch"? Why did the question of his race never even come up in his contentious trials and the newspaper coverage of them? And what are we to make of a fellow officer in the Revenue Service, a man apparently sympathetic to the political nativism of the 1890s, who a few years before had told Healy that he had "no place as an officer of the U.S. government" because he was a Catholic?(23) Wouldn't that man have found a more telling reason to argue Healy's disqualification if he had any inclination of his background? No, we are probably right to presume that people are most truthful and least calculating when they are calling other people names. The absence of racial insult in these cases indicates the success with which Captain Healy was able to define himself as white rather than black.

Today the Coast Guard is today building an icebreaker that it will name for him in honor of his role as the first black captain in the service—an identification about which he would have been, at best, ambivalent. In spite of the opportunities that African Americans might have had on the sea or on the untamed frontier, Michael Healy dared not present himself, or indeed even think of himself, as black. His siblings had made the same choice. His brothers James, Sherwood, and Patrick all spoke of "the negro" as if they were talking about someone else, even during Reconstruction, when the status of blacks in America was the most important public issue of the day.(24) No matter how much ability or courage Michael Healy had in doing his duty, his advancement in the Revenue Service during the 1880s and 1890s, just as Jim Crow legislation was taking hold in the South and racial discrimination was hardening North and South, would surely have been impeded had his racial origins been known. If he was to have his career, it had to be as a white man.

Such choices and deliberate decisions on his part were not supposed to be possible, for a person's race was thought to be settled by that unalterable matter of blood. In the case of Michael Healy and his family, however, we see that racial identity could be not a given, but rather a matter of one's own choosing. Moreover, the apparent ease with which they made the transition from black to white is striking. Perhaps individuals do indeed have more choice in such matters than we have thought. Perhaps crossing the color line was neither so difficult nor so personally costly as we have supposed. Beyond that, the lives of the Healys demonstrate the means by which racial choices may be made and the important role that intermediate institutions and identities play in softening the predetermining power we are disposed to assign to race alone. In finding a third "thing" to be--Catholic priests and nuns in the case of his siblings, a government officer in Michael Healy's case--they could at least partially escape the effects of the stark polarity between black and white, and in so doing claim a power of their own.

Notes

1. Testimony of Michael A. Healy, Mar. 20, 1890, in "Charges Against RCS Officers: Capt. M. A. Healy," box 11, Records of the Revenue Cutter Service, Record Group 26, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC (hereinafter, records in the National Archives will be cited as RG __, NARA); "Address of the Official Prosecutor," [January 1896], box 12, ibid.

2. Michael Healy's naturalization oath, Apr. 3, 1818, is in Deed Book K (1818–1819): 144, Jones County Courthouse, Gray, GA.

3. I have reconstructed Michael Healy's land and slave holdings from the records of the Jones County Court of Ordinary, microfilm copies of which are available in the Georgia Department of Archives and History, Atlanta. For an understanding of his social and economic context, see Joseph P. Reidy, From Slavery to Agrarian Capitalism in the Cotton Plantation South: Central Georgia, 1800-1880 (1992), and William T. Jenkins, "Ante Bellum Macon and Bibb County" (Ph.D. diss.: University of Georgia, 1966).

4. Michael Healy's will, dated Feb. 28, 1845, and the codicil to it, dated July 6, 1847, are both in Jones County Will Book C, pp. 412-416, microfilm copy in the Georgia Department of Archives and History. He could not actually use the word "wife" to describe Eliza, for that was a legal impossibility and to do so would have risked invalidating the will completely. For similar cases of interracial marriage in antebellum Georgia, see Adele Logan Alexander, Ambiguous Lives: Free Women of Color in Rural Georgia, 1789–1879 (1991), and Kent Anderson Leslie, Woman of Color, Daughter of Privilege: Amanda America Dickson, 1849–1893 (1995).

5. The classic studies of white American attitudes about race are Winthrop D. Jordan, White Over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550–1812 (1968), and George M. Fredrickson, The Black Image in the White Mind: The Debate on Afro-American Character and Destiny, 1817–1914 (1971). On interracial sexuality and its human results, see John G. Mencke, "Mulattoes and Race Mixture: American Attitudes and Images from Reconstruction to World War I" (Ph.D. diss.: University of North Carolina, 1978); Leonard R. Lempel, "The Mulatto in United States Race Relations: Changing Status and Attitudes, 1800–1940" (Ph.D. diss.: Syracuse University, 1979); and Joel Williamson, New People: Miscegenation and Mulattoes in the United States (1980).

6. On the phenomenon of passing, see Williamson, New People, pp. 101–106; Paul R. Spickard, Mixed Blood: Intermarriage and Ethnic Identity in Twentieth-Century America (1989), pp. 335–336; John H. Burma, "The Measurement of Negro Passing,'" American Journal of Sociology 52 (July 1946): 18-22; James E. Conyers and T. H. Kennedy, "Negro Passing: To Pass or Not To Pass," Phylon 24 (Fall 1963): 215–223. On double consciousness and marginality, see W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (1903, reprint 1990), p. 13, and Everett V. Stonequist, The Marginal Man: A Study in Personality and Culture Conflict (1937), esp. chap. 2.

7. The literature on this subject is large and still growing. See especially Werner Sollors, Beyond Ethnicity: Consent and Descent in American Culture (1986); Barbara J. Fields, "Ideology and Race in American History," Region, Race, and Reconstruction: Essays in Honor of C. Vann Woodward, ed. by J. Morton Kousser and James M. McPherson (1982), pp. 143–177; Michael Omi and Howard Winant, Racial Formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1980s (1986); and Thomas C. Holt, "Marking: Race, Race-Making, and the Writing of History," American Historical Review 100 (February 1995): 1–20.

8. Overviews of this remarkable family may be found in three books by Albert S. Foley: Bishop Healy: Beloved Outcaste (1954); God's Men of Color: The Colored Catholic Priests of the United States, 1854–1954 (1955); and Dream of an Outcaste: Patrick F. Healy (1976). For a briefer but more recent treatment, see Cyprian Davis, The History of Black Catholics in the United States (1990), pp. 146–152.

9. James A. Healy diary, Aug. 14, 1849, James A. Healy Papers, Archives, College of the Holy Cross, Worcester, MA. Patrick Healy's passports, Oct. 30, 1858, and Dec. 19, 1885, Registers and Indexes for Passport Applications, 1810–1906 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M1371, rolls 3 and 5), General Records of the Department of State, RG 59, NARA. There is also a copy of the 1885 passport in the Patrick F. Healy Papers, Archives, Georgetown University, Washington, DC.

10. Patrick Healy to Fenwick, Nov. 23, 1853, Maryland Jesuit Province Archives, box 74, folder 1, Archives, Georgetown University.

11. Patrick Healy to Fenwick, Dec. 11, 1854, and James Healy to Fenwick, Dec. 22, 1854, Maryland Jesuit Province Archives, box 74, folder 15, Archives, Georgetown University; Michael Healy to Cornell, Jan. 18, 1865, Revenue Cutter Service Application Files, box 12, RG 26, NARA.

12. Healy to Cornell, Jan. 18, 1865, Revenue Cutter Service Application Files, box 12, RG 26, NARA. Healy's file contains several letters of endorsement from captains and others who could attest to his seamanship. For the work of the service in these years, see Stephen H. Evans, The United States Coast Guard, 1790–1915, with a Postscript, 1915–1950 (1949).

13. See the several letters of recommendation in the Revenue Cutter Service Application Files, box 12, RG 26, NARA: Fitzpatrick to Fessenden, Oct. 15, 1864; Andrew to Harrington, Nov. 19, 1864; and Bacon to Fessenden, Dec. 20, 1864.

14. On the opportunities available to blacks in seafaring, see Martha S. Putney, Black Sailors: Afro-American Merchant Seamen and Whalemen Prior to the Civil War (1987); W. Jeffrey Bolster, " 'To Feel Like a Man': Black Seamen in the Northern States," Journal of American History 76 (March 1990): 1173–1199; and David L. Valuska, The African American in the Union Navy, 1861–1865 (1993).

15. The marriage of Michael Healy and Mary Jane Roach, which was presided over by the groom's brother James, is noted in Bishop's Journal, Jan. 31, 1865, Archives, Archdiocese of Boston, Boston, MA.

16. Register of Revenue Cutter Service Officers, 1790–1914, Vol. 1, p. 125, RG 26, NARA. For descriptions of the early American presence in Alaska, see Ernest Gruening, The State of Alaska (rev. 1968); William R. Hunt, Arctic Passage: The Turbulent History of the Land and People of the Bering Sea, 1679–1975 (1975); Elmo P. Hohman, The American Whaleman: A Study of Life and Labor in the Whaling Industry (1928); and Evans, Coast Guard, pp. 105–139.

17. Evans, Coast Guard, pp. 129–130.

18. On the reindeer scheme, see ibid., pp. 131–133. See also Gruening, State of Alaska, pp. 94-96, and Hunt, Arctic Passage, pp. 178–181. Sheldon Jackson himself wrote an account of these efforts: "The Arctic Cruise of the United States Revenue Cutter Bear,'" National Geographic Magazine 7 (January 1896): 27–31. A reasonably accurate fictional portrayal of Healy and Jackson is presented in part seven of James A. Michener's Alaska (1988).

19. New York Sun, Jan. 28, 1894; "Testimonial to Captain M. A. Healy," Dec. 2, 1889, Healy Collection, box 3, Huntington Library, San Marino, CA; Mary Jane Healy Diary (HM 47579), Sept. 22, 1890, Healy Collection, Huntington Library.

20. "Testimony Taken at the Investigation into the Conduct of Captain M. A. Healy," March 3–22, 1890, in "Charges Against RCS Officers: Capt. M. A. Healy, box 11, RG 26, NARA; undated clipping, San Francisco News Letter; Mary Jane Healy Alaska Scrapbook (HM 47616), Healy Collection, box 2, Huntington Library.

21. Records of Healy's second trial are in "Charges Against RCS Officers: Capt. M. A. Healy," box 11, RG 26, NARA; see especially "Address of the Official Prosecutor," [Jan. 1896], box 12. See also his service record: Register of Revenue Cutter Service Officers, 1790–1914, Vol. 1, pp. 125, 82, RG 26, NARA. The suicide attempt and the incidents surrounding it are recorded in the logbook of the USRCS McCulloch, July 7–13, 1900, RG 26, NARA; on this particularly troubling episode, see Gary C. Stein, "A Desperate and Dangerous Man: Captain Michael A. Healy's Arctic Cruise of 1900," Alaska Journal 15 (Spring 1985): 39–45. See also Gerald O. Williams, "Michael J. [sic] Healy and the Alaska Maritime Frontier, 1880–1902" (Ph.D. diss.: University of Oregon, 1987), which is marred by many factual errors and a generally unsympathetic tone toward Healy.

22. See, for example, Healy to Commissioner of Education, Dec. 17, 1894, Alaska File of the Revenue Cutter Service, 1867–1914 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M641, roll 3), RG 26, NARA; Healy to Shepard, July 4, 1893, ibid.; and Healy to Clark, Sept. 12, 1881, ibid. On his son's perceptions of himself and his family, see the diary of Fred Healy (HM #47577), July 25, 1883, Healy Collection, Huntington Library.

23. Healy to Shepard, Dec. 14, 1892, M641, roll 2, RG 26, NA.

24. In commenting on Radical Republican plans for Reconstruction, James expressed his skepticism about "the equalization . . . of the negro": Bishop's Journal, Dec. 4, 1865, Archives, Archdiocese of Boston. Sherwood spoke of "the negro" in a school exercise in which he argued that slavery itself was not inherently immoral, though the slave trade was; see his "The Church and Negro Slavery," A. Sherwood Healy Papers, Archives, College of the Holy Cross. Patrick made similarly detached observations about "the negroes" he encountered while crossing the Isthmus of Panama; see his diary, Dec. 9 and 16, 1879, Patrick F. Healy Papers, Archives, Georgetown University.