“First in the Path of the Firemen”

The Fate of the 1890 Population Census

Spring 1996, Vol. 28, No. 1 | Genealogy Notes

By Kellee Blake

Of the decennial population census schedules, perhaps none might have been more critical to studies of immigration, industrialization, westward migration, and characteristics of the general population than the Eleventh Census of the United States, taken in June 1890. United States residents completed millions of detailed questionnaires, yet only a fragment of the general population schedules and an incomplete set of special schedules enumerating Union veterans and widows are available today. Reference sources routinely dismiss the 1890 census records as "destroyed by fire" in 1921. Examination of the records of the Bureau of Census and other federal agencies, however, reveals a far more complex tale. This is a genuine tragedy of records—played out before Congress fully established a National Archives—and eternally anguishing to researchers.

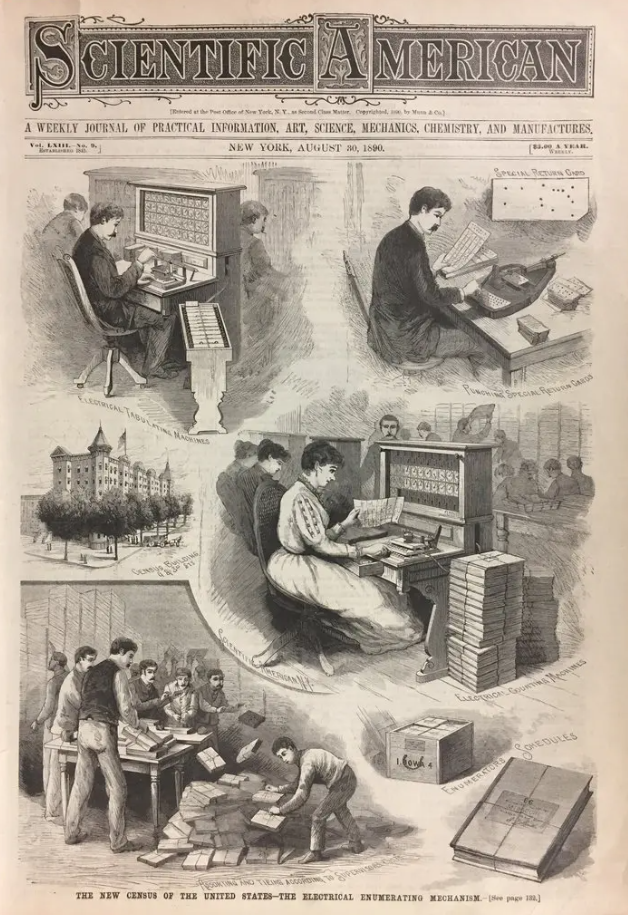

As there was not a permanent Census Bureau until 1902, the Department of the Interior administered the Eleventh Census. Political patronage was "the most common order for appointment" of the nearly 47,000 enumerators; no examination was required. British journalist Robert Porter initially supervised the staff for the Eleventh Census, and statistician Carroll Wright later replaced him.(1) This was the first U.S. census to use Herman Hollerith's electrical tabulation system, a method by which data representing certain population characteristics were punched into cards and tabulated. The censuses of 1790 through 1880 required all or part of schedules to be filed in county clerks' offices. Ironically, this was not required in 1890, and the original (and presumably only) copies of the schedules were forwarded to Washington.(2)

June 1, 1890, was the official census date, and all responses were to reflect the status of the household on that date. The 1890 census law allowed enumerators to distribute schedules in advance and later gather them up (as was done in England), supposedly giving individuals adequate time to accurately provide information. Evidently this method was very little used. As in other censuses, if an individual was absent, the enumerator was authorized to obtain information from the person living nearest the family.(3)

The 1890 census schedules differed from previous ones in several ways. For the first time, enumerators prepared a separate schedule for each family. The schedule contained expanded inquiries relating to race (white, black, mulatto, quadroon, octoroon, Chinese, Japanese, or Indian), home ownership, ability to speak English, immigration, and naturalization. Enumerators asked married women for the number of children born and the number living at the time of the census to determine fecundity. The 1890 schedules also included a question relating to Civil War service.(4)

Enumerators generally completed their counting by July 1 of 1890, and the U.S. population was returned at nearly 63 million (62,979,766). Complaints about accuracy and undercounting poured into the census office, as did demands for recounts. The 1890 census seemed mired in fraud and political intrigue. New York State officials were accused of bolstering census numbers, and the intense business competition between Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota, resulted in no fewer than nineteen indictments against Minneapolis businessmen for allegedly adding more than 1,100 phony names to the census. Perhaps not surprisingly, the St. Paul businessmen brought the federal court complaint against the Minneapolis businessmen.(5)

In March 1896, before final publication of all general statistics volumes, the original 1890 special schedules for mortality, crime, pauperism and benevolence, special classes (e.g., deaf, dumb, blind, insane), and portions of the transportation and insurance schedules were badly damaged by fire and destroyed by Department of the Interior order.(6) No damage to the general population schedules was reported at that time. In fact, a 1903 census clerk found them to be in "fairly good condition."(7) Despite repeated ongoing requests by the secretary of commerce and others for an archives building where all census schedules could be safely stored, by January 10, 1921, the schedules could be found piled in an orderly manner on closely placed pine shelves in an unlocked file room in the basement of the Commerce Building.

At about five o'clock on that afternoon, building fireman James Foster noticed smoke coming through openings around pipes that ran from the boiler room into the file room. Foster saw no fire but immediately reported the smoke to the desk watchman, who called the fire department.(8) Minutes later, on the fifth floor, a watchman noticed smoke in the men's bathroom, took the elevator to the basement, was forced back by the dense smoke, and went to the watchman's desk. By then, the fire department had arrived, the house alarm was pulled (reportedly at 5:30), and a dozen employees still working on upper floors evacuated. A total of three alarms and a general local call were turned in.(9)

After some setbacks from the intense smoke, firemen gained access to the basement. While a crowd of ten thousand watched, they poured twenty streams of water into the building and flooded the cellar through holes cut into the concrete floor. The fire did not go above the basement, seemingly thanks to a fireproofed floor. By 9:45 p.m. the fire was extinguished, but firemen poured water into the burned area past 10:30 p.m. Disaster planning and recovery were almost unknown in 1921. With the blaze extinguished, despite the obvious damage and need for immediate salvage efforts, the chief clerk opened windows to let out the smoke, and except for watchmen on patrol, everyone went home.(10)

The morning after was an archivist's nightmare, with ankle-deep water covering records in many areas. Although the basement vault was considered fireproof and watertight, water seeped through a broken wired-glass panel in the door and under the floor, damaging some earlier and later census schedules on the lower tiers. The 1890 census, however, was stacked outside the vault and was, according to one source, "first in the path of the firemen."(11) That morning, Census Director Sam Rogers reported the extensive damage to the 1890 schedules, estimating 25 percent destroyed, with 50 percent of the remainder damaged by water, smoke, and fire.(12) Salvage of the water-soaked and charred documents might be possible, reported the bureau, but saving even a small part would take a month, and it would take two to three years to copy off and save all the records damaged in the fire. The preliminary assessment of Census Bureau Clerk T. J. Fitzgerald was far more sobering. Fitzgerald told reporters that the priceless 1890 records were "certain to be absolutely ruined. There is no method of restoring the legibility of a water-soaked volume."(13)

Four days later, Sam Rogers complained they had not and would not be permitted any further work on the schedules until the insurance companies completed their examination. Rogers issued a state-by-state report of the number of volumes damaged by water in the basement vault, including volumes from the 1830, 1840, 1880, 1900, and 1910 censuses. The total number of damaged vault volumes numbered 8,919, of which 7,957 were from the 1910 census. Rogers estimated that 10 percent of these vault schedules would have to be "opened and dried, and some of them recopied." Thankfully, the census schedules of 1790–1820 and 1850–1870 were on the fifth floor of the Commerce Building and reportedly not damaged. The new 1920 census was housed in a temporary building at Sixth and B Streets, SW, except for some of the nonpopulation schedules being used on the fourth floor.(14)

Speculation and rumors about the cause of the blaze ran rampant. Some newspapers claimed, and many suspected, it was caused by a cigarette or a lighted match. Employees were keenly questioned about their smoking habits. Others believed the fire started among shavings in the carpenter shop or was the result of spontaneous combustion. At least one woman from Ohio felt certain the fire was part of a conspiracy to defraud her family of their rightful estate by destroying every vestige of evidence proving heirship.(15) Most seemed to agree that the fire could not have been burning long and had made quick and intense headway; shavings and debris in the carpenter shop, wooden shelving, and the paper records would have made for a fierce blaze. After all, a watchman and engineers had been in the basement as late as 4:35 and not detected any smoke.(16) Others, however, believed the fire had been burning for hours, considering its stubbornness. Although, once the firemen were finished, it was difficult to tell if one spot in the files had burned longer than any other, the fire's point of origin was determined to have been in the northeastern portion of the file room (also known as the storage room) under the stock and mail room.(17) Despite every investigative effort, Chief Census Clerk E. M. Libbey reported, no conclusion as to the cause was reached. He pointed to the strict rules against smoking, intactness of electrical wires, and noted that no rats had been found in the building for two months. He further reasoned that spontaneous combustion in bales of waste paper was unlikely, as they were burned on the outside and not totally consumed.(18) In the end, even experts from the Bureau of Standards brought in to investigate the blaze could not determine the cause.(19)

The disaster spurred renewed cries and support for a National Archives, notably from congressmen, census officials, and longtime archives advocate J. Franklin Jameson.(20) It also gave rise to proposals for better records protection in current storage spaces. Utah's Senator Reed Smoot, convinced a cigarette caused the fire, prepared a bill disallowing smoking in some government buildings. The Washington Post expressed outrage that the Declaration of Independence and Constitution were in danger even at the moment, being stored at the Department of State in wooden cabinets.(21)

Meanwhile, the still soggy, "charred about the edges" original and only copies of the 1890 schedules remained in ruins. At the end of January, the records damaged in the fire were moved for temporary storage. Over the next few months, rumors spread that salvage attempts would not be made and that Census Director Sam Rogers had recommended that Congress authorize destruction of the 1890 census. Prominent historians, attorneys, and genealogical organizations wrote to new Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, the Librarian of Congress, and other government officials in protest. The National Genealogical Society (NGS) and Daughters of the American Revolution formally petitioned Hoover and Congress, and the editor of the NGS Quarterly warned that a nationwide movement would begin among state societies and the press if Congress seriously considered destruction.(22) The content of replies to the groups was invariably the same; denial of any planned destruction and calls for Congress to provide for an archives building. Herbert Hoover wrote "the actual cost of providing a watchman and extra fire service [to protect records] probably amounts to more, if we take the government as a whole, than it would cost to put up a proper fire-proof archive building."(23)

Still no appropriation for an archives was forthcoming. By May of 1921 the records were still piled in a large warehouse where, complained new census director William Steuart, they could not be consulted and would probably gradually deteriorate. Steuart arranged for their transfer back to the census building, to be bound where possible, but at least put in some order for reference.(24)

The extant record is scanty on storage and possible use of the 1890 schedules between 1922 and 1932 and seemingly silent on what precipitated the following chain of events. In December 1932, in accordance with federal records procedures at the time, the Chief Clerk of the Bureau of Census sent the Librarian of Congress a list of papers no longer necessary for current business and scheduled for destruction. He asked the Librarian to report back to him any documents that should be retained for their historical interest. Item 22 on the list for Bureau of the Census read "Schedules, Population . . . 1890, Original." The Librarian identified no records as permanent, the list was sent forward, and Congress authorized destruction on February 21, 1933. At least one report states the 1890 census papers were finally destroyed in 1935, and a small scribbled note found in a Census Bureau file states "remaining schedules destroyed by Department of Commerce in 1934 (not approved by the Geographer)."(25) Further study is necessary to determine, if possible, what happened to the fervent and vigilant voices that championed these schedules in 1921. How were these records overlooked by Library of Congress staff? Who in the Census Bureau determined the schedules were useless, why, and when? Ironically, just one day before Congress authorized destruction of the 1890 census papers, President Herbert Hoover laid the cornerstone for the National Archives Building

In 1942 the National Archives accessioned a damaged bundle of surviving Illinois schedules as part of a shipment of records found during a Census Bureau move. At the time, they were believed to be the only surviving fragments.(26) In 1953, however, the Archives accessioned an additional set of fragments. These sets of extant fragments are from Alabama, Georgia, Illinois, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, South Dakota, Texas, and the District of Columbia and have been microfilmed as National Archives Microfilm Publication M407 (3 rolls). A corresponding index is available as National Archives Microfilm Publication M496 (2 rolls). Both microfilm series can be viewed at the National Archives, the regional archives, and several other repositories. Before disregarding this census, researchers should always verify that the schedules they seek did not survive. There are no fewer than 6,160 names indexed on the surviving 1890 population schedules. These are someone's ancestors.

The Special Enumeration of Union Veterans and Widows

Often confused with the 1890 census, and more often overlooked or misjudged as useless, are nearly seventy-five thousand special 1890 schedules enumerating Union veterans and widows of Union veterans.(27) Nearly all of these schedules for the states of Alabama through Kansas and approximately half of those for Kentucky appear to have been destroyed before transfer of the remaining schedules to the National Archives in 1943. Nearly all, but fragments for some of these states were accessioned by the National Archives as bundle 198. Many reference sources state or speculate that the missing schedules were lost in the 1921 fire. The administrative record, however, does not support this conclusion.

The Pension Office requested the special enumeration to help Union veterans locate comrades to testify in pension claims and to determine the number of survivors and widows for pension legislation. Some congressmen also thought it scientifically useful to know the effect of various types of military service upon veterans' longevity.(28) To assist in the enumeration, the Pension Office prepared a list of veterans' names and addresses from their files and from available military records held by the War Department. The superintendent of the census planned to print in volumes the veterans information (name, rank, length of service, and post office address) compiled from the 1890 enumeration and place copies with libraries and veterans organizations so individuals could more easily locate their fellow veterans.(29)

Question 2 on the general population schedules inquired whether the subject had been "a soldier, sailor, or marine during the civil war (United States or Confederate) or widow of such person." Enumerators were instructed to write "Sol" for soldier, "Sail" for sailor, and "Ma" for marine, with "U.S." or "Conf." in parentheses, for example, Sol (U.S.) or Sail (Conf.). The letter "W" was added to these designations if the enumerated was a widow.(30) According to enumeration instructions, if the veteran or widow responded "yes" to Union service, the enumerator produced the veterans schedule, marked the family number from the general population schedule, and proceeded to ask additional service-related questions.

The upper half of each page on the veterans schedules lists name, rank, company, regiment or vessel, date of enlistment, date of discharge, and length of service. The lower half contains the post office address, any disability incurred in the service, and general remarks. The question on disability was included because many veterans claimed pensions, under an 1862 act, based on service-related disabilities.(31) The "General Remarks" column usually provides the most colorful, anecdotal, and meaningful information on the schedules.

Although the special enumeration was intended only for Union veterans of the Civil War and their widows, enumerators nevertheless often listed veterans and widows of earlier wars as well as Confederate veterans.(32) Veterans of the War of 1812 are sometimes listed, and there are especially numerous entries for Mexican War veterans. Susan Arnold of Pennsylvania was listed, though her husband died in New Orleans coming home from the Seminole War (1828–1833).

John Yost is listed as serving in the French army under Maximilian. Several sources note that Confederates are inadvertently recorded in this enumeration; actual study of the records reveals that there are some Confederates listed for every extant state (excluding the fragments on bundle 198). Schedules consisting nearly entirely of Confederates are not altogether uncommon, especially in extant schedules of Southern states.(33) The Confederate names are sometimes crossed out or marked as errors (presumably by census supervisors), but the information is usually readable.

Listings for widows can also provide telling insights to the veteran's service, her life or remarriage, even their relationship. Eliza Smith of Pennsylvania was simply listed as the "grass widow of a soldier." A Pennsylvania widow living at the Home for the Friendless claimed she knew nothing of her husband's fate but thought him dead. A Wyoming widow remembered no particulars, only that her husband wore a "blue coat." Enumerators were instructed to list the widow's name above the name of the deceased veteran and fill out the record of his service during the war but list her present post office. Remarried widows were listed in this manner with their new surname. Dependent mothers are also sometimes listed, as in the case of Pate Halberts of Ohio, who knew little English, but enough to tell the enumerator her son died in Andersonville.(34)

Enumerators often noted the battle or circumstances in which a death or disability had been incurred, such as "shot dead at Gettysburg, July 3rd 1864" or "lost right arm at Resaca." They also had the unenviable task of diagnosing the described ailments such as "harte disease," "indestan of stomic," and "thie woond." Men recounted the loss of eyes, ears, and appendages. They told of falling from and being trampled by horses, being crippled on trains "wrecked by rebels," and going insane from the "noise of war." Allan Hobbs of Salt Lake, Utah, claimed partial paralysis of his feet from freezing in Libbey Prison, and George Search of Baltimore claimed his constitution was broken after six months at Andersonville.(35) The perils of bad wartime medicine are evident as well. Many reported blood poisoning or crippling from an impure vaccination. One widow told the enumerator her husband died by eating too much morphine. Without a doubt, however, the most widespread permanent disabilities reported by the 1890 veterans were diarrhea (spelled in many creative ways) and piles.

The schedules may reveal anecdotal or unique information. They sometimes briefly chronicle an individual's military career, like that of William Martin of North Carolina, who rose from private to general. Josiah Dunbar's widow claimed her husband was one of the first, if not the first, to enlist in his county, and Bernard Todd remembered he had played in Custer's band at the Appomattox surrender. Ohioan James Stabus admitted he had been captured and paroled by the notorious raider John Hunt Morgan. Jackson Mitchell of Pennsylvania said he was born a slave and compelled at first to serve in the Confederate army. Others proudly noted their service in the U.S. Colored Troops, in specialized units, or as spies. Dennis Arnold of Allegany, Maryland, said he "would go again tomorrow." The schedules may even provide clues about enlistment under "secret or varied names." For example, Samuel Polite, Marcus Moultair, and August Gadson of Sheldonship County, South Carolina, all reported they had enlisted in the Union Army under "secret" names, which the enumerator listed according to instructions, with lawful name preceding the alias.(36) In some instances, the pension certificate number is provided. At least two Missourians were listed on the veterans schedule and overlooked in the general population census.(37)

A less noble side of some veterans is revealed, as well. Some individuals falsely claimed to be veterans, hoping to receive government pensions. "Deserter" is entered in the remarks column often enough, although it is often unclear by whom this information was provided. William Robertson of the Oklahoma Territory was found "sick on drink when visited." One North Carolina enumerator disgustedly reported on a case of pension fraud, noting: "Brown and Branvell were both deserters from the Confederate Army. Brown now draws a pension from 'Uncle Sam' under the plea that he has scurvy of the mouth."(38)

At the completion of the 1890 enumeration, the special schedules were returned with a preliminary count of 1,099,668 Union survivors and 163,176 widows. A large number of schedules were found to be incomplete, and many veterans had been overlooked. The Census Bureau sent thousands of letters and published inquiries in hundreds of newspapers hoping to acquire missing data. As appropriate, corrections and additions were made to the schedules. The initial work of examining, verifying, and classifying the information was suspended in June 1891, awaiting congressional appropriation for publication of the veterans' volumes.(39) During that same period, anticipating the publication, the bureau began transcribing information from the schedules onto a printed card for each surviving veteran or widow, later to be arranged by state and organization. No fewer than 304,607 cards were completed before this work was also halted. These cards do not seem to be extant, nor does there appear to be a final record of their disposition. Some cards may have been placed in individual service files.(40)

The veterans' publication seemed doomed. Adequate funding was not available, many considered other census work more pressing, and searches for information in the manuscript veterans schedules were cumbersome and costly. In 1893 Carroll Wright, then in charge of the census, argued that too much time had already passed to make any veterans' publication accurate; the general schedules provided an approximate number of Union veterans and widows. He recommended these special schedules be transferred to the Pension Office or the War Department, and in 1894 Congress authorized their transfer to the Commissioner of Pensions for use in the Pension Office and transferred them "shortly thereafter."(41) The schedules were arranged and stored in bundles, generally alphabetically by name of state or territory, and numbered sequentially. In 1930 legal custody of the schedules passed from the Pension Office to the newly formed Veterans Administration, where they remained until accessioned by the National Archives in 1943 as part of Record Group 15.(42) Clearly these schedules were maintained apart from the population schedules and used for different purposes in a different location. Moreover, no reporting from the fires of 1896 or 1921 mention these schedules among the damaged series. It seems nearly impossible they were involved in the Commerce Building fire in 1921.

The extant schedules are available for part of Kentucky through Wyoming, Lincoln Post #3 in Washington, D.C., and selected U.S. vessels and navy yards. The schedules are generally arranged by state and county and thereunder generally by town or post office address. The bundle containing schedules for Oklahoma and Indian Territories are arranged by enumeration districts. Although veterans schedules from the states of Alabama through Kentucky (part) are not known to be extant, bundle 198 on roll 118, "Washington, DC, and Miscellaneous," also contains some schedules for California (Alcatraz), Connecticut (Fort Trumbull, Hartford County Hospital, and U.S. Naval Station), Delaware (Delaware State Hospital for the Insane), Florida (Fort Barrancas and St. Francis Barracks), Idaho (Boise Barracks and Fort Sherman), Illinois (Cook County and Henderson County), Indiana (Warrick County and White County), and Kansas (Barton County). All of the accessioned schedules have been microfilmed and are available as National Archives Microfilm Publication M123 (118 rolls).(43)

There is no comprehensive index to the 1890 special enumeration, but indexes to some states or specific areas have been prepared by various publishing companies and private groups. These special enumerations are well worth examination. Although it may be time-consuming to wade through an unindexed county, the information rewards can be priceless and uncommon. Few series in the National Archives rival this one for anecdotal information and local color.

Of course, there is no real substitute for the lost 1890 or any other comprehensive federal census. Records relating to elections, tax or criminal legislation, impending statehood, war, economic crisis, vital statistics reporting, and other local events may provide alternative information sources. There are some state and territorial censuses available for the years near 1890. For example, the federal government assisted the states and territories of Colorado, Florida, Nebraska, New Mexico, and the Dakotas in an 1885 census. There is an 1890 territorial census for some areas in Oklahoma.(44) The 1890 poll lists or "Great Registers" for selected counties in Arizona and California are extant and available at the respective state archives. The Arkansas Genealogical Society has sponsored a statewide program to reconstruct the missing 1890 federal census using tax and other local records. Ann Lainhart's State Census Records (Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 1992) includes state-by-state listings of census resources, including some census and other alternatives for the 1890 federal census.(45) Researchers are encouraged to contact state and local repositories to inquire about alternative resources and verify records arrangement, availability, and content.

The loss of the 1890 schedules and absence of part of the special veterans enumeration are especially painful information losses for which there is no real balm. However, all of the federal censuses (pre-1920) might have been destroyed in that 1921 fire, especially if it had consumed the entire Commerce Building. It is a wonder now, as it was to the secretary of commerce at the time of the fire, that such a large number of records were saved.(46) Most researchers in federal records are frustrated at some point by gaps in records, lack of indexes and description, poor quality images, or unknown records provenance. More than 150 years passed between the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the establishment of a U.S. National Archives, however, and the nation paid a high price for this delay. Critical records succumbed to war, fire, flood, theft, moves, agency reorganization, administrative error, improper filming, ignorance, apathy, and the ravages of time. It is really quite remarkable that so many valuable records are extant and available for research. The tragedy of the 1890 census remains a constant reminder of the necessity for a vigorous National Archives and unrelenting vigilance about the historical record.

Notes

1. Daniel P. O'Mahony, "Lost But Not Forgotten: The U.S. Census of 1890," Government Publications Review 18 (1991): 332; Margo J. Anderson, The American Census: A Social History (1988), p. 106.

The Census Bureau was established as a permanent organization in 1902; before that date, the work of the bureau was carried out on an ad hoc basis pursuant to congressional authorization. In February 1903 the Census Bureau was transferred from the Department of the Interior to the Department of Commerce and Labor and in 1913 to the newly separated Commerce Department. See Kellee Green, "The Fourteenth Numbering of the People: The 1920 Federal Census," Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives 23 (Summer 1991): 131–132.

2. O'Mahony, "Lost But Not Forgotten," pp. 333, 335; Anderson, The American Census, p. 102; W. Stull Holt, The Bureau of the Census: Its History, Activities, and Organization (1929; reprint, 1974), p. 30.

Municipal governments could request copies of information (names, age, sex, birthplace, and color or race) of their residents from the superintendent of the census at a cost of twenty-five cents for each hundred names. See Sec. 23, An Act to Provide for Taking of the Eleventh and Subsequent Censuses, March 1, 1889, Records Relating to the 11th (1890) Census, 1889-1893, Records Relating to Decennial Censuses, Patents and Miscellaneous Division, Records of the Office of the Secretary of Interior, Record Group 48, National Archives (hereinafter, records in the National Archives will be cited as RG ___, NA); Carroll D. Wright and William C. Hunt, The History and Growth of the United States Census (1900), p. 73.

3. There were four general schedules relating to the population, agriculture, manufactures, and mortality; eight supplemental schedules, for the defective, dependent, and delinquent classes; and a special schedule enumerating the survivors of the War of the Rebellion. Sec. 9, 19, An Act to Provide for Taking of the Eleventh and Subsequent Censuses, March 1, 1889, and Robert V. Porter to Eugene Hale, Feb. 21, 1890, Records Relating to the 11th (1890) Census, 1889 1893, Records Relating to Decennial Censuses, Patents and Miscellaneous Division, RG 48, NA; Richard Mayo Smith. "The Eleventh Census of the United States," Economic Journal 1 (March 1891): 45-46; Wright and Hunt, History and Growth, p. 70.

4. Holt, The Bureau of the Census, p. 28; Sec. 17, An Act to Provide for Taking of the Eleventh and Subsequent Censuses, March 1, 1889, and Robert V. Porter to Eugene Hale, Feb. 21, 1890, Records Relating to the 11th (1890) Census, 1889-1893, Records Relating to Decennial Censuses, Patents and Miscellaneous Division, RG 48, NA.

On the population schedule there were fourteen inquiries common to the schedules of 1880 and 1890, while in 1890 there were ten additional points of information:

- Whether a soldier, sailor, or marine during the Civil War (United States or Confederate), or widow of such person.

- Mother of how many children, and number of these children living (for all married, widowed, and divorced women).

- Number of years in the United States (for all foreign-born adult males).

- Whether naturalized (for all foreign-born adult males).

- Whether naturalization papers have been taken out (for all foreign-born adult males).

- Ability to speak English (for all persons ten years old and upward).

- Whether home lived in was hired, or owned by the head or by a member of the family.

- If owned by head or member of family, whether the home was free from mortgage incumbrance.

- If the head of the family was a farmer, whether the farm which he cultivated was hired, or owned by him or by a member of his family.

- If owned by head or member of family, whether the farm was free from mortgage incumbrance.

In 1890 a further subdivision was required by the law concerning negroes of mixed blood as to the number of mulattoes, quadroons, and octoroons. See Robert Porter to Hon. J. H. Gallinger, ordered to be printed Jan. 5, 1898, 55th Cong., 2d sess., Document 46.

5. Introduction to File Microcopies of Records in the National Archives: No. 123, Eleventh Census of the United States, 1890, Schedules Enumerating Union Veterans and Widows of Union Veterans of the Civil War (1948), p. ii; Wright, History and Growth, p. 76; Smith, "The Eleventh Census," p. 49; Anderson, The American Census, pp. 106, 108; Report of the Operations of the Census Office for the Fiscal Year ended June 30, 1892, Records Relating to the 11th (1890) Census, Records Relating to Decennial Censuses, Patents and Miscellaneous Division, RG 48, NA; U.S. v. Stevens, et al., Criminal Case 105, U.S. District Court for the District of Minnesota Fourth Division (Minneapolis), Records of District Courts of the United States, RG 21, National Archives-Central Plains Region.

6. Anderson, The American Census, p. 109; Wright and Hunt, History and Growth, p. 78.

In his annual report for 1937, the Archivist of the United States, reporting the accessioning of farm schedules from other census years, noted: "The agricultural schedules for 1850, 1860, 1870, and 1880 have been distributed to societies and libraries throughout the country; those for 1890 have disappeared." See Third Annual Report of the Archivist of the United States for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1937 (1938), pp. 141-142.

7. C. S. Sloane to Edward McCauley, Nov. 24, 1903, folder "Census of 1890," Alphabetical Subject File, Records of the Bureau of the Census, RG 29, NA.

Perhaps, retrospectively, it is amazing that a fire did not occur sooner, as a 1916 report notes that the area in the vault nearest the boiler room could not be kept below 90 degrees while the heating plant was in operation, making it too hot for a clerk to work in the vault for more than a few minutes and causing the records to rapidly deteriorate. Report of the Secretary of Commerce 1916, General Correspondence 68636/3, Office of the Secretary, General Records of the Department of Commerce, RG 40, NA.

8. "Report Concerning the Fire in the Basement of the Department of Commerce Building on the Afternoon of January 10, 1921," Jan. 20, 1921, and Testimony of James E. Foster, Fireman, Testimony of John Parsons, Chief Engineer and Electrician, Office of the Solicitor's Inquiry Concerning Origin of the Fire in the Department of Commerce Building on January 10, 1921, made January 11, 1921, General Correspondence 68636/3; Office of the Secretary, RG 40, NA; Washington Star, Jan. 11, 1921; Washington Post, Jan. 11, 1921.

9. The January 20 report of Libbey and the Washington Post state 5:30 as the time the fire was discovered. "Report Concerning the Fire in the Basement of the Department of Commerce Building on the Afternoon of January 10, 1921," Jan. 20, 1921, and Report, E. M. Libbey to the Secretary of Commerce, Jan. 20, 1921, General Correspondence 68636/3, Office of the Secretary, RG 40, NA; Washington Post, Jan. 11, 1921; Washington Herald, Jan. 11, 1921.

10. Washington Post, Jan. 11, 1921; Washington Star, Jan. 11, 1921; Testimony of William M. Lytle, Chief Clerk, Bureau of Navigation, Testimony of Chancellor, Watchman, Office of the Solicitor's Inquiry Concerning Origin of the Fire in the Department of Commerce Building on January 10, 1921, made January 11, 1921, and Report, E. M. Libbey to the Secretary of Commerce, Jan. 20, 1921, General Correspondence 68636/3, Office of the Secretary, RG 40, NA.

11. Washington Post, Jan. 11, 1921; Washington Star, Jan. 11, 1921; Washington Herald, Jan. 11, 1921; J. W. Alexander, Secretary of Commerce, to Harry Wardman, Jan. 22, 1921, General Correspondence 68636/3, Office of the Secretary, RG 40, NA; New York Times, Jan. 11, 1921, quoted in O'Mahony, "Lost But Not Forgotten," p. 335.

Chief Engineer Parsons claimed the water was 14-16 inches deep when he inspected it on January 11. See Testimony of John Parsons, Chief Engineer and Electrician, Office of the Solicitor's Inquiry Concerning the Origin of the Fire in the Department of Commerce Building on January 10, 1921, made January 11, 1921, General Correspondence 68636/3, Office of the Secretary, RG 40, NA.

12. Washington Herald, Jan. 11, 1921; Sam L. Rogers to the Secretary of Commerce, Jan. 11, 1921, and Testimony of John Parsons, Chief Engineer and Electrician, Office of the Solicitor's Inquiry Concerning the Origin of the Fire in the Department of Commerce Building on January 10, 1921, General Correspondence 68636/3, Office of the Secretary, RG 40, NA.

Other later estimates place the destruction at 15-25%. See Evangeline Thurber, "The 1890 Census Records of the Veterans of the Union Army," NGS Quarterly 34 (March 1946): 8. G. M. Brumbaugh, editor of the NGS Quarterly, claimed in April 1921 that the fire destroyed records of about 6,000 enumeration districts and badly charred about 2,000 other districts out of some 41,000 districts, although he does not provide the source of his data. See G. M. Brumbaugh, M.D., to Senator Miles Poindexter, Apr. 8, 1921, and G. M. Brumbaugh, to Herbert Putnam, Librarian of Congress, Apr. 8, 1921, folder "Census of 1890," Alphabetical Subject File, Records of the Bureau of the Census, RG 29, NA.

13. Washington Post, Jan. 11, 1921; Washington Star, Jan. 11, 1921; New York American, Jan. 11, 1921.

14. Rogers reported the following "number of bound volumes and of portfolios of census schedules which were damaged by water in the vault in the basement of the Commerce Building during the fire of January 10": census volumes from the 1830 census (6 states, 53 volumes), 1840 census (7 states, 65 volumes), 1880 census (20 states, 211 volumes), 1900 census (17 states and the Indian Territory, 633 volumes), and 1910 census (48 states and the District of Columbia, 7,957 volumes). He noted that it would be impossible to tell the extent of the damage until the schedules were taken out of the vault, dried, and examined. Sam L. Rogers to the Secretary of Commerce, Jan. 11, 1921, General Correspondence 68636/3, Office of the Secretary, RG 40, NA; Washington Herald, Jan. 11, 1921.

15. J. W. Alexander to Hon. Wesley L. Jones, Feb. 2, 1921, "Report Concerning the Fire in the Basement of the Department of Commerce Building on the Afternoon of January 10, 1921," Jan. 20, 1921, and Testimony of John Parsons, Chief Engineer and Electrician, Office of the Solicitor's Inquiry Concerning Origin of the Fire in the Department of Commerce Building on January 10, 1921, made January 11, 1921, General Correspondence 68636/3, Office of the Secretary, RG 40, NA; Washington Star, Jan. 13, 14, 1921.

Mrs. J. C. Drysdale noted that there had been fires in the three most critical sources of her heirship evidence: in the Census Bureau, in the Capitol at Virginia, and at the Old City Hall in Columbus, OH. "Another fact that makes these three fires appear as the work of an incendiary is the fact that they were almost simultaneous, just enough time between for one man to travel from Va. to Washington, and from there to Columbus, and then to Cleveland to get his reward." Mrs. J. C. Drysdale to T. G. Fitzgerald, Mar. 31, 1921, General Correspondence 68636/3, Office of the Secretary, RG 40, NA.

16. Washington Star, Jan. 11, 14, 1921; Washington Post, Jan. 11, 1921; Washington Herald, Jan. 11, 1921; Congressional Record, 66th Cong., 3d sess., 1921, Vol. 60, No. 29, p. 1320; "Report Concerning the Fire in the Basement of the Department of Commerce Building on the Afternoon of January 10, 1921," Jan. 20, 1921, Report, E. M. Libbey to the Secretary of Commerce, Jan. 20, 1921, and Testimony of Edward M. Chancellor, Watchman, Office of the Solicitor's Inquiry Concerning Origin of the Fire in the Department of Commerce Building on January 10, 1921, made January 11, 1921, General Correspondence 68636/3, Office of the Secretary, RG 40, NA.

17. "Report Concerning the Fire in the Basement of the Department of Commerce Building on the Afternoon of January 10, 1921," Jan. 20, 1921, Testimony of John Parsons, Chief Engineer and Electrician, Testimony of Walter Pumphrey, Chief Watchman, Testimony of W. S. Erwin, Clerk in the Supply Division, Office of the Solicitor's Inquiry Concerning Origin of the Fire in the Department of Commerce Building on January 10, 1921, made January 11, 1921, E. M. Libbey to the Secretary of Commerce, Jan. 20, 1921; General Correspondence 68636/3, Office of the Secretary, RG 40, NA; Washington Star, Jan. 13, 1921.

18. Report, E. M. Libbey to the Secretary of Commerce, Jan. 20, 1921, E. M. Libbey to Charles E. Stewart, Chief Clerk, Department of Justice, Apr. 16, 1921, General Correspondence 68636/3, Office of the Secretary, RG 40, NA.

19. Washington Star, Jan. 24, 1921.

20. William C. Redfield, to J. W. Alexander, Jan. 12, 1921, and Washington Star, Jan. 11, 1921, General Correspondence 68636/3, Office of the Secretary, RG 40, NA; J. Franklin Jameson to Hoover, May 11, 1921, Hoover to Jameson, May 14, 1921, Jameson to Hoover, May 21, 1921, Hoover-Jameson Correspondence, Herbert Hoover Library, West Branch, IA.

21. Washington Star, Jan. 13, 16, 17, 1921; Washington Post, Jan. 11, 1921; General Correspondence 68636/3, Office of the Secretary, RG 40, NA.

22. Washington Star, Jan. 24, 29, 1921; S. W. Stratton [?], Bureau of Standards, to Secretary of Commerce, Jan. 26, 1921, General Correspondence 68636/3, Office of the Secretary, RG 40, NA; various correspondence, G. M. Brumbaugh, M.D., editor, NGS Quarterly, to Senator Miles Poindexter, Apr. 8, 1921, National Genealogical Society Resolutions to Save the Population Census of 1890, Washington, DC, Apr. 2, 1921, Resolution, Apr. 22, 1921, signed by Emma L. Strider, Register General of the Daughters of the American Revolution, et al., folder "Census of 1890," box 9, Alphabetical Subject File, entry 160, RG 29, NA.

23. Herbert Hoover told inquirers that there must be some "mis-impression about this matter as I have no notion of destroying any records." He also noted that the records were in constant jeopardy, placed as they were in a temporary war building. Herbert Hoover to Burton L. French, May 6, 1921, and sheet, "Census of 1890," n.d., folder "Census of 1890," Alphabetical Subject File, entry 160, RG 29, NA.

24. W. M. Steuart to the Secretary of Commerce, May 3, 1921, folder "Census of 1890," box 9, Alphabetical Subject File, entry 160, RG 29, NA; Annual Report of the Director of the Census to the Secretary of Commerce for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1922 (1922), p. 26.

25. Disposition of Useless Papers in the Department of Commerce, 2d sess., No. 2080; Thurber, "The 1890 Census," p. 8; Note, n.d., signed E.L.Y, folder "Census of 1890," box 9, Alphabetical Subject File, entry 160, RG 29, NA.

E.L.Y. is presumably Evelyn L. Yeomans, on the staff of the Geography Division from 1899 to 1941, who "apparently maintained the Division files and answered requests for information from and about the old census schedules." See Katherine H. Davidson and Charlotte B. Ashby, comps., Records of the Bureau of Census: National Archives Preliminary Inventory 161 (1964), p. 53.

26. A few schedules from Illinois are reported accessioned in the Eighth Annual Report of the Archivist of the United States for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1942 (1943), p. 71. See also Final Report on Transfer, Accession No. 947 Recommendation on Transfer, by Robert Claus, Acting Associate Archivist, Job 42-154, Jan. 22, 1942, Accession 947 Dossier, NA.

27. The accession dossier notes some 74,344 original copies of the "Eleventh Census of the United States, Special Schedules," in the accession. This number was based on the preliminary estimate of schedules given by the Veterans Administration. Recommendation on Transfer, Dorothy Hill, Mar. 24, 1943, Final Report on Transfer, Dorothy Hill, June 17, 1943, and Frank T. Hines, Administrator, Veterans Administration, to Solon J. Buck, Archivist of the United States, Sept. 14, 1942, Job 43-74, Accession 1369 Dossier, NA.

28. By 1890, more than 250,000 claims had been rejected or were awaiting adjudication in the Pension Office because witnesses to support the claims could not be located. See Thurber, "The 1890 Census," p. 7; Recommendation on Transfer, Dorothy Hill, Mar. 24, 1943, Job 43-74, Accession 1369 Dossier, NA; Carroll D. Wright to the Secretary of the Interior, Nov. 18, 1893, Records Relating to the 11th (1890) Census, 1889 1893, Records Relating to Decennial Censuses, Patents and Miscellaneous Division, RG 48, NA.

29. Porter to Hale, Dec. 12, 1889, Records Relating to the 11th (1890) Census, 1889-1893, Records Relating to Decennial Censuses, Patents and Miscellaneous Division, RG 48, NA; introduction to Special Schedules of the Eleventh Census (1890) Enumerating Union Veterans and Widows of Union Veterans of the Civil War (National Archives Microfilm Publication M123), p. ii.

30. Wright and Hunt, History and Growth, p. 187.

31. 12 Stat. L. 566, as quoted in Gustavus A. Weber and Laurence F. Schmeckebier, The Veterans Administration: Its History, Activities, and Organization (1934), p. 40.

32. Enumerators received five cents (in per capita payment areas) for each record on the special schedule for surviving veterans, possibly encouraging additional or incorrect entries. Others claim the incorrect entries resulted from improper or imprecise phrasing of the question regarding veterans' service. Wright and Hunt, History and Growth, p. 72.

33. Susan Arnold, Pennsylvania, Special Schedules of the Eleventh Census, M123, roll 91.

34. Eliza Smith, Pennsylvania, roll 91; Margaret Montgomery, Pennsylvania, roll 91; Widow, Wyoming, roll 117; and Pate Halberts, Ohio, roll 73, all on Special Schedules of the Eleventh Census, M123.

35. Allan T. Hobbs, Utah Territory, Special Schedules of the Eleventh Census, M123, roll 103.

36. William Martin, North Carolina, roll 58; James Stabus, Ohio, roll 73; Bernard Todd, Pennsylvania, Jackson Mitchell, Pennsylvania, roll 81; and Samuel Polite, Marcus Moultair, and August Gadson, roll 93, all on Special Schedules of the Eleventh Census, M123. Wright and Hunt, History and Growth, pp. 198-199.

37. Dennis Arnold, Maryland, roll 10, and William Luilbett, Jacob Lasa, Missouri, roll 32, all on Special Schedules of the Eleventh Census, M123.

38. William Robertson, Oklahoma Territory, Roll 76, M123; Brown, North Carolina, Special Schedules of the Eleventh Census, M123, roll 57.

39. Thurber, "The 1890 Census," pp. 7–8; Letter, Acting Superintendent of Census to the Secretary of the Interior, Sept. 12, 1893, and Carroll D. Wright to Secretary of the Interior, Nov. 18, 1893, Records Relating to the 11th (1890) Census, 1889-1893, Records Relating to Decennial Censuses, Patents and Miscellaneous Division, RG 48, NA; introduction to Special Schedules of the Eleventh Census, M123, pp. ii-iii; Holt, The Bureau of the Census, p. 30; typewritten note, E.L.Y, Aug. 29, 1934, folder "Census of 1890," Alphabetical Subject File, RG 29, NA; Routing Slip, Dorothy J. Hill, 4-26-43, Job 43-74, Accession 1369 Dossier, NA.

40. Carroll D. Wright to the Secretary of the Interior, Nov. 18, 1893, Records Relating to the 11th (1890) Census, 1889-1893, Records Relating to Decennial Censuses, Patents and Miscellaneous Division, RG 48, NA; Thurber, "The 1890 Census," p. 9; Wright and Hunt, History and Growth, p. 75.

In the printed reports of the commissioner of pensions for the fiscal years 1895 and 1896, it was stated that this division had made some 437,538 additions to the cards in the "service files." See Job 43-74, Accession 1369 Dossier, NA.

41. Acting Superintendent of Census to Secretary of Interior, Sept. 20, 1893, Acting Superintendent of Census to the Secretary of the Interior, Sep. 12, 1893, and Carroll D. Wright to the Secretary of the Interior, Nov. 18, 1893, Records Relating to the 11th (1890) Census, 1889-1893, Records Relating to Decennial Censuses, Patents and Miscellaneous Division, RG 48, NA; Thurber, "The 1890 Census," p. 8; Holt, The Bureau of the Census, p. 30; typewritten note, E.L.Y, Aug. 29, 1934, folder "Census of 1890," Alphabetical Subject File, RG 29, NA; introduction to Special Schedules of the Eleventh Census, M123, p. iii; routing slip, Dorothy J. Hill, 4-26-43, Job 43-74, Accession 1369 Dossier, NA.

42. Introduction to Special Schedules of the Eleventh Census, M123, p. iii; Holt, Bureau of the Census, p. 30; typewritten note, E.L.Y., Aug. 29, 1934, folder "Census of 1890," Alphabetical Subject File, RG 29, NA; Recommendation on Transfer, Dorothy Hill, Mar. 24, 1943, routing slip, Apr. 23, 1943, Final Report on Transfer, June 17, 1943, and interoffice communication, Arthur H. Leavitt, May 20, 1943, Job 43-74, Accession 1369 Dossier, NA; Ninth Annual Report of the Archivist for the Fiscal Year Ending June 1943 (1944), p. 86; Wright and Hunt, History and Growth, p. 79.

The records apparently came to the National Archives from the Dependents Claims Service at the Veterans Administration. Final Report on Transfer, June 17, 1943; routing slip, Apr. 26, 1943, Job 43-74, Dossier, Accession 1369, NA.

43. Introduction to Special Schedules of the Eleventh Census, M123, p. iii.

44. Guide to Genealogical Research in the National Archives (1985), pp. 25–35.

45. Microfilmed copies are available via the Family History Library in Salt Lake City and the California section of the State Library in Sacramento. Wendy L. Elliott, "'Great Register Project' Aims to Replace Missing 1890 Census," Federation of Genealogical Societies Forum 4 (Summer 1992): 3 4; Alice Eichholz, ed., Redbook: American State, County, and Town Sources (1989), p. 32; Ann S. Lainhart, State Census Records (1992).

46. J. W. Alexander to William C. Redfield, Jan. 17, 1921, General Correspondence 68636/3, Office of the Secretary, RG 40, NA.