The Little Regiment

Civil War Units and Commands

Summer 1995, Vol. 27, No. 2

By Michael P. Musick

When Stephen Crane (1871–1900) chose the title The Little Regiment for his 1896 collection of short stories set during the Civil War, he knew what he was about. He knew that phrase would resonate with his readers, that it would have a special meaning for veterans, and for many nonveterans as well.

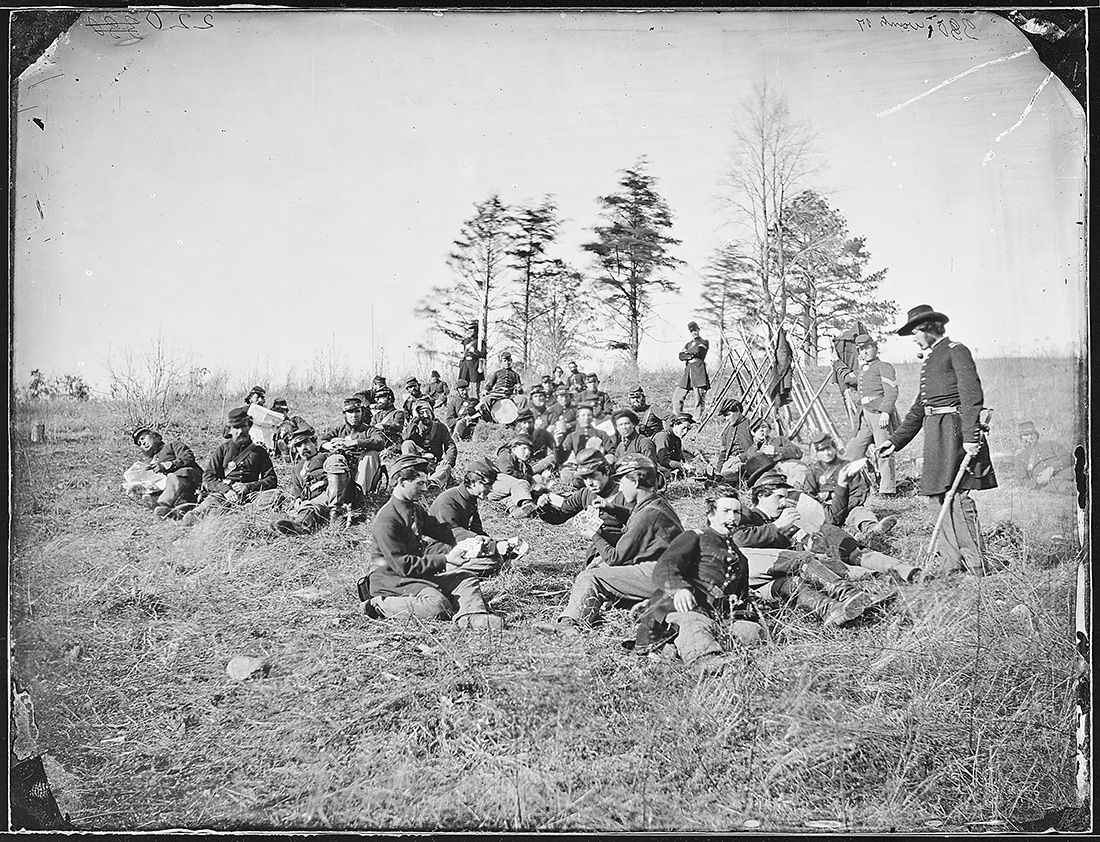

Crane knew what many in later years forgot: that for the Civil War generation, a regimental designation was not merely a military convenience. In truth, the regiment was the primary object of identification for the men who fought the war. For the most part, a unit meant neighbors, friends, and in many cases (as in the story that gave Crane his title) blood relatives. To speak the name of a unit was often to summon up a host of associations within a particular state and community.

And so the call to arms introduced into Federal or Confederate service an array of units with names like the Kalamazoo Light Guard and the Sumter Light Guards, the Brooklyn Phalanx and the Winchester Boomerangs—volunteer companies accepted by the governors of the states, combined into regiments, and tendered to the central government. Other names held other associations: the DeKalb Regiment (men of German birth), the Irish Jasper Greens (sometime denizens of the Emerald Isle), and the Louisiana Native Guards (men of color, first under the Stars and Bars, and later the Stars and Stripes). Fusileers followed Fencibles in serried ranks, their names lending panache to outfits rich in elegant uniforms if not in combat experience.

Many of these units were of company strength, supposed to number between 83 and 101 men. Confederate authorities specified a minimum of 64 privates, and a maximum of 125. Ten such companies of infantry, plus the field and staff officers, usually formed a regiment. Cavalry and artillery regiments were designed to have twelve companies. For the horsemen, each company was 100 strong. For light artillery, each company (called a battery) was to have no more than 150 men with six cannon.

The rugged realities of active service meant that, in practice, such numbers were often dramatically reduced, making many regiments little indeed. Eventually unit identifies were transformed into designations as prosaic as Company I, Second Michigan Infantry; Company K, Fourth Georgia Infantry; or the Seventy-third Regiment, United States Colored Infantry. This being the Civil War, anomalies abounded. The Second Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery was in reality two regiments, with more than five thousand men passing through the ranks. The Twenty-eighth Pennsylvania Infantry boasted fifteen companies, lettered A through P. At least Sixty-two unattached Confederate companies served. Some were more independent than others. From Illinois came Capt. Thorndike Brooks's company, which went south to become Company G, Fifteenth Tennessee Infantry, C.S.A.

With time, of course, a particular history clung to each unit. It became a matter of intense pride to say that one had served in one of "Fox's 300 Fighting Regiments" (a list of regiments with the highest casualties, published by Union veteran William F. Fox in 1889). It also became necessary to be familiar with particular designations if one was to understand the service of their members. Hence the need to know that "The Mississippi Marine Brigade" was a Union army volunteer organization that served on gunboats on the Father of Waters rather than a Confederate contingent from the Magnolia State; that the six regiments of United States Volunteer Infantry were composed of Confederate prisoners of war who agreed to fight on the frontier against Indians; and that the Confederate First Foreign Battalion was raised from Union soldiers confined in North Carolina.

As might be expected with forces numbering in the millions, basic organizational terminology could sometimes be confusing. A popular name for an organization smaller than a regiment was a battalion, usually commanded by a lieutenant colonel or major. It could have anywhere from two to nine companies. The U.S. Regular Army, following the French system, introduced a three-battalion arrangement for each of its infantry regiments raised during the Civil War itself (the Eleventh U.S. Infantry through the Nineteenth U.S. Infantry), a practice that muddies understanding. Since the regular army was numerically of no great consequence, however, its organizational peculiarities are customarily ignored with impunity. Likewise, more than a dozen "legions" of the Confederacy (formations including infantry, cavalry, and artillery) are statistically overshadowed by the more familiar regimental arrangement.

Other, higher commands, of which the regiment was a part, were also means of identification. These were the brigade, division, army corps, and army, in ascending magnitude. Names such as the Iron Brigade, the Stonewall Brigade, Cleburne's Division, Syke's Division, Hardee's Corps, the Sixth Corps, the Army of the Cumberland, or the Army of Northern Virginia conveyed a cachet that became a significant part of the way the war was experienced.

All of these command designations represent important information that can aid in researching and understanding the conflict and in furnishing background for individual lives. In this hierarchy the regiment stands out as of special significance, especially since no individual service numbers had yet been devised to distinguish one John C. Jones from another. While a service record ordinarily provides only the bare bones of a soldier's history, a knowledge of what his unit did when he was with it, what its distinctive character was, as well as the personalities of its commanders and its triumphs and disasters, puts flesh on the bones and enhances our understanding of what it meant to be a particular person at a particular time in a particular unit.

More than that, the regiment is a building block in a stairway leading to all manner of explorations. For example, when unearthing the history of a locality, a county, or a building, knowledge of which units were there may take one to rich and varied source material, retrievable in no other way. Similarly, documentation on units can open the door to the details of battles, campaigns, and skirmishes. Unit affiliation can unlock the experience of Latinos, Native Americans, African Americans, Irishmen, Germans, and other ethnic and religious groups. When it came to forming military bodies, ethnic or racial groups in nineteenth-century America joined together in military units to fight.

Records in the National Archives relating to regiments (a term used here to include battalions, batteries, legions, etc.) are rewarding and voluminous. However, they are the raw material of history rather than history itself. The Federal and Confederate War Departments did not demand of the regiments that they compile narrative histories, and so such histories were not compiled under government auspices. That task fell to the veterans as private citizens, if it was accomplished at all. Committees of survivors, chaplains, or keenly interested individuals took it upon themselves to tell the stories of their outfits, beginning in some cases during the conflict and in others as late as the second decade of the twentieth century. These hundreds of published unit histories, although they vary tremendously in quality, scope, and content, are generally the first place to turn to learn about a given unit. They should be sought in historical libraries rather than in the National Archives.

An outline sketch of the history of every Union regiment, regular and volunteer, will be found in Frederick H. Dyer's magnificent, privately produced A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion. No comprehensive Confederate equivalent of Dyer's Compendium exists at present, though several efforts in this direction are extremely helpful (See Appendix C, "Confederate Army Regimental Books"). Not every Confederate unit has a published version of its history. Because of a dearth of documentation for the more obscure outfits, these gaps are not likely to change soon. Nevertheless, when they exist, the single-volume published unit history, devoted to one Union or Confederate organization, is generally the most valuable source on its subject. They are popularly styled "regimentals" and customarily include a unit roster, sometimes profuse illustrations with portraits and scenes, and almost always a connected narrative of service written by a participant.

Charles E. Dornbusch, a bibliographer with the New York Public Library, painstakingly constructed the gateway to these published regimentals. The unit histories portion of his labors will be found in the first two volumes of his monumental Military Bibliography of the Civil War. Volume 1 contains listings for most of the Union volunteer units. Volume 2 includes Union, Southern, border, and Western states and territories and troops raised directly by the federal government, as well as all Confederate units, with biographies of personalities on both sides thrown in for good measure. Volume 4 brings the bibliographic coverage up to 1987. All of the unit histories in Dornbusch are available on microfiche under the title Civil War Unit Histories: Regimental Histories and Personal Narratives by University Publications of America, Bethesda, Maryland.

A few words of introduction for users of the Dornbusch bibliography are in order. An important list of abbreviations for frequently cited works appears early in each section and, among other things, explains abbreviations used in the lists of reference works preceding each state subsection. The lists of state reference works are particularly notable because they provide the titles of publications that have information on every regiment from a given state. There follow listings by arm of service (artillery, cavalry, infantry) and then by number or name.

To illustrate the approach, in volume 1 is a section for Indiana and Ohio. On page 78 of this section are listings for the 105th Ohio Infantry, beginning with dates of organization and muster-out of service, and proceeding with a citation to the Official roster of the soldiers of the state of Ohio in the War of the Rebellion, 1861–1866 . . . compiled under direction of the Roster Commission . . . published by authority of the general assembly (1886–1895) in twelve volumes, a state-sponsored work that supplies the names of Ohio soldiers by unit, gives some service data, and has a single-paragraph summary of the unit's service. The 105th Ohio is shown to be in volume 7, on pages 570–598, and 774–780. Most Northern and some Southern states have printed rosters of their troops, varying widely in format and quality.

Dornbusch cites an additional work on all Buckeye units (one that gives a fuller narrative of the regiment) and then lists three publications on the 105th, including a splendid production by Albion W. Tourgée, a feisty jurist, novelist, and veteran of the outfit, titled The Story of A Thousand (Dornbusch-Ohio #392), which in style and depth demonstrates why "the regimental" is an enduring cornerstone of Civil War literature. Symbols ("DLC," "NN"), whose explanations are unfortunately not provided in the volume, indicate libraries in which the compiler located copies (e.g., the Library of Congress, Washington, DC, and the New York Public Library). Most librarians will have a key to the library symbols, and one is printed on the end-papers of the National Union Catalog of Pre-1956 Imprints, issued by the Library of Congress. The Online Computer Library Catalog (OCLC) is another useful tool for locating these publications. Unfortunately, among the notable items missed in Dornbusch's bibliography are the many Confederate titles in The Virginia Regimental Histories series, begun in 1982. The OCLC is especially helpful in filling the chronological void. The Library of Congress catalogs these works under "United States History, Civil War 1861–1865, Regimental Histories."

Among the best sources for unit history are official battle reports (in modern parlance, after-action reports), official letters and telegrams, and tables of organization (more recently called order of battle). These records for the most part are now a part of the National Archives. Because of their importance, however, the War Department printed a good many of these in its monumental 128-volume War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (1880–1901). A companion series issued by the Navy Department and an accompanying Atlas help to make the Official Records an indispensable research tool (for greater detail, see "Honorable Reports: Battles, Campaigns, and Skirmishes" Prologue 27 (Fall 1995). Not all such material was printed, but the published volumes have many such sources, and they are widely available.

Persons wishing to use the Official Records for unit history need to keep in mind that they are indexed in a manner unfamiliar to twentieth-century readers. State volunteer regiments are found by examining the "General Index" under the state designation (such as "Georgia Troops (C)," for Georgia Confederates), then "Infantry-Regiments," then "4th," for the Fourth Georgia Infantry of the Confederate army. These steps lead to a series (numbered I through IV), and then an individual volume number. Arabic numerals must be translated into roman numerals, and the same subject then looked up in the index to the pertinent volume for specific page numbers. Other troops will be found under such headings as "United States Colored Troops" or "United States Regulars." In general, indexers of the Civil War era used the state as the primary index term, while many indexers of the past few decades, unfamiliar with the conventions of the subject, use references such as "Fourth Georgia Infantry," using the unit number as the primary item of identification. Recent variations are numerous.

Many authors and filmmakers have used unpublished personal letters and diaries to good effect. These sources are to be found outside the National Archives. For the purposes of unit history, some (but far from all) of them can be found indexed in a style almost identical to that of the Official Records indexers in the National Union Catalog of Manuscript Collections. Likewise, John R. Sellers's Civil War Manuscripts: A Guide to Collections in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress employs categories such as "Georgia Troops," though it placed regular units under "U.S. Army" and United States Colored Troops under "Black troops."

Published letters and diaries, particularly those that appeared later than the coverage in Dornbusch, can be located in profusion in Civil War Eyewitnesses: An Annotated Bibliography of Books and Articles, 1955–1986 (1988), by Garold L. Cole, using the familiar state rubric. Cole indexes corps, regular army units, and U.S. Colored Troops under "United States Army," the Colored Troops under the additional subdivision, "Volunteer units. Colored." By definition, Cole does not list unit histories compiled by modern historians.

Newspapers, particularly small-town papers published in the localities in which a unit was raised, generally printed letters written home by soldiers themselves. Such letters, though by publication no longer private, do not fit the category "official." These letters have no comprehensive bibliography or listing, nor do unit histories that appeared in newspapers years after the conflict. In such cases, intrepidity and imagination on the part of the researcher will help a great deal. Two periodicals with much on Confederate units, the Southern Historical Society Papers and Confederate Veteran Magazine, now have good indexes, and other such indexes are in preparation.

The most complete and authoritative records relating to Civil War units are those in the National Archives. Numerous units, particularly on the Confederate side and Southern Union outfits, have little or no published history, and there is a good chance that the National Archives records will fill those gaps. Two microfilm publications, M594, Compiled Records Showing Service of Military Units in Volunteer Union Organizations, and M861, Compiled Records Showing Service of Military Units in Confederate Organizations, often flesh out the stories of such unsung outfits. The utility of these records (also called "Records of Events" or "Caption Cards") is very uneven, particularly for Confederates, even within the same unit from one report to the next. Many of these records were left blank by the troops or filled in perfunctorily with a phrase such as "In the field, Tennessee." They are currently being published in letterpress edition as Part II of the Supplement to the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Wilmington, N.C., 1994– ), edited by Janet B. Hewett, beginning with serial 13.

Unit records of the war were kept according to the army Regulations, the Confederate version being virtually identical to that of the U.S. Army.1 The primary difference between the contending armies in this respect was that the Confederate troops rarely created the required descriptive books, with information on place of birth, age on enlistment, and physical description. When they do exist (and even federal records can have gaps in this respect), the descriptive books of both sides include lists of commissioned and noncommissioned officers, registers of men transferred, discharged, deceased, and deserted, as well as entries for each soldier in the unit. Descriptive books were supposed to be maintained at both the regimental and company level and would in theory contain the same information for each man in a given company, but in practice they frequently do not overlap when they should. Some people always seemed to be left out. The only complete roster for a Union unit is the Compiled Military Service Records. For some Confederate units, no complete roster is possible.

The bound records of the Union volunteer regiments (RG 94, entries 112–115) are a magnificent source for unit history, and one little exploited.2 All told there are some 8,713 unique volumes of these records, sent to the Adjutant General's Office in compliance with general orders. Most of these volumes are combinations of several smaller ones. The Record and Pension Office of the War Department in the 1890s rebound the records, combining slim volumes together to form new, thicker, and less unwieldy tomes. Thus the individual company descriptive books of the Ninth Indiana Infantry regiment are bound together to form two volumes, one for Companies A through E, and another for Companies F through K. Many of the clothing account books were de-accessioned by the National Archives and can be found in places like the Pennsylvania State Archives in Harrisburg (for Keystone State outfits), and the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Manuscript Division, at Howard University in Washington, DC (430 volumes from the U.S. Colored Troops).

In addition to the standard books required, many units kept a variety of miscellaneous items. A few random examples are a register of absentees; a "history of the 183d Pennsylvania"; a register of charges, arrests, and confinements; a memorandum book of the Third Kentucky Cavalry (which has notations on scouts, movements, and charges preferred); guard reports; and regimental casualties and lists of men furloughed in the Ninth New Jersey Infantry. A "journal" in a volume for the Thirty-fifth Missouri Infantry for September 30, 1862–July 13, 1863, includes these remarks for February 26: "Came ten miles today. The quartermaster went to hunt some corn to feed the staff officers horses and went to a house where thare [sic] had been a fight and in the fight a small girl had been shot in the head[.] a sergeant went and dressed the wound."

Some individualistic recordkeepers put down additional information beyond what was required on standard records. A descriptive book of Company E, 114th Pennsylvania Infantry (Collis's Zouaves D'Afrique) includes the Philadelphia street addresses of the soldiers. A descriptive book of Company I, Fifty-sixth U.S. Colored Infantry, raised in Adams County, Mississippi, shows the names of the former owners of the soldiers. The same kind of record for Company A, 110th Pennsylvania Infantry, furnishes the names of battles and skirmishes in which the men participated.

These records are physically in poor condition, the imitation leather bindings now crumbling, producing an irksome dust ("red rot"), which covers the hands of users. Dr. Richard J. Sommers of the U.S. Army Military History Institute, Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, says that it represents "Truly, the Red Badge of Courage earned by Civil War scholars!" Some of the information in the regimental volumes will be found elsewhere. The descriptive books were usually "carded" (transcribed), and such battle reports as appear in them usually found their way into the published Official Records. Nonetheless, they present a detailed picture of soldier life found nowhere else, from orders specifying the daily schedule, reveille to tattoo, to directions for the line of march, the equipment to be carried into action, and admonitions on the appearance of the outfit. Capt. John S. Buckles's Order No. 11 of December 20, 1861, from the headquarters of the Ninth Illinois Cavalry, illuminates the difficulty in controlling volunteers in the first year of conflict and hints at the kind of thing that may have led Buckles to resign his commission soon after:

Hereafter, if any man gets drunk when he has a pass to go out of camp He will not get a pass again. The Captain desires if any man wants to get drunk, that he do it upon his own responsibility and not upon a pass granted by the Captain. If a man realy wants to get drunk and cant get along without it, if he will inform the Captain of it he will Himself go and get Whiskey For Him and let him get drunk right in camp where he can be taken care of and not be liable to be caught by the patrol and placed in the Guard House.

A second major source of unpublished documents significant for the history of Union volunteer regiments are the unbound regimental papers, which (at this writing) are filed with muster rolls. The papers for the U.S. Colored Troops units have been conveniently separated from the muster rolls and are consequently more readily accessible. The regimental papers, rarely used, are especially notable because they exist for every unit, including many for which there are no bound records.

The regimental papers are of many kinds and are much more numerous for some units than for others. Typically, they will include such things as quarterly returns of deceased soldiers, monthly returns, inspection reports, orders issued and received, letters received, telegrams, lists of deserters and absentees, and court-martial charges and specifications. Almost anything can turn up in these hodge-podges. Some unusual examples have included photographs of soldiers, personal letters, and brief narrative histories.

The bound and unbound records are notable for the great extent to which they cover the numerous regiments of U.S. Colored Troops, most of which have no published unit history. Both bound and unbound records are listed by regiment and category in National Archives Special List No. 33, Tabular Analysis of the Records of the U.S. Colored Troops and Their Predecessor Units in the National Archives of the United States. For example, records in these two categories (but not compiled military service and pension records), plus muster rolls, are reproduced on National Archives Microfilm Publication M1659, Records of the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Infantry Regiment (Colored), 1863–1865.

Further sources for documentation on Union volunteer units are plentiful. The researcher who declares an intention (as some have) to locate "every scrap of paper on the unit" faces an impossibility. The volume of potential sources in the National Archives alone is overwhelming. Simply absorbing the Compiled Military Service Records and pension records is daunting for many. At least a few further possibilities should be mentioned. Court-martial and court of inquiry records, which can be key to understanding an organization's experience, are in Record Group 153, Records of the Judge Advocate General's Office. Registers of the Records of the Proceedings of the U.S. Army General Courts-Martial, 1809–1890 (M1105), contains an index organized by the name of the soldier being tried (or under "I" for Inquiry in a few cases), with unit affiliation shown after the soldier's name. The court of inquiry on the capture of Charles Town, West Virginia, on October 18, 1863 (file MM 1256), to give one instance, is a virtual history of the Ninth Maryland Infantry, which was overwhelmed there. Medal of honor case documentation, though not arranged or indexed by unit, can provide vivid details of combat, particularly for applications made years after the event. The microfilmed Index to General Correspondence of the Record and Pension Office (M686), 1889–1904 (not to be confused with an index to pensions), which is indexed by outfit, is liable to lead to a variety of files on any aspect of an organization's history or status. And despite the various printed sources, nothing gives a sense of the sad and inglorious career of the 145th New York Infantry, from its raising to its dissolution by consolidation with other units, like the Volunteer Service Division files (S 2112 V.S. 1863, P 11 12 V. S. 1862, W 468 V. S. 1863, and V 128 V. S. 1863) of RG 94, entry 496, found through index references to field officers. This review suggests only the most likely of the many avenues for research on Federal volunteer regiments.

Unlike the volunteers, the regulars published few regimental histories of the war. This difference makes their manuscript records all the more significant. The records created and maintained by regular units were under different administrative control than those of the volunteers. Today the bound and unbound unit records of the regulars for 1861–1865 are part of Record Group 391, Records of U.S. Regular Army Mobile Units, 1821–1942 (formerly in Record Group 98, and so described in Munden and Beers, The Union: Guide to Federal Archives Relating to the Civil War [1962; reprinted 1961). They are described for each unit in National Archives inventory NM-93, issued in 1970. Of course, since many of these units existed before, during, and after the Civil War, many series such as "regimental letters sent" do not begin in 1861 and end in 1865.

The original, quite fragile muster rolls of the regular army, most still folded, are in Record Group 94, Records of the Adjutant General's Office. They are arranged by time period (1821–1860; 1860–1912), then by arm, regiment (beginning with field, staff, and band rolls), and by company, with detachment rolls and some unbound records for more than one company at the end. These rolls have never been transcribed onto Compiled Military Service Records, nor have they been reproduced on National Archives microfilm publications. This status is true also for the valuable "Record of Events" section on the rolls, which were generally better filled in than those by volunteers. The result is that regular units are not represented on National Archives Microfilm Publication M594. One category of regular army unit records that has been microfilmed are the monthly regimental returns.

These returns are primarily a statistical accounting of numbers of troops present and absent, but they also provide much other data useful to regimental historians such as the stations of companies and the names and status of all officers. They are available as National Archives Microfilm Publications: M665, Returns From Regular Army Infantry Regiments, June 1821–Dec. 1916; M744, Returns From Regular Army Cavalry Regiments, 1833–1916; M727, Returns From Regular Army Artillery Regiments, June 1821–Jan. 1901; M690, Returns From Regular Army Engineer Battalions, Sept. 1846–June 1916; M851, Returns of the Corps of Engineers, April 1832–Dec. 1916; and M852, Returns of the Corps of Topographical Engineers, Nov. 1831–Feb. 1863. The volunteer returns, when they exist, are filed with unit muster rolls in RG 94, entry 57.

Published Confederate unit histories are more numerous than those for the U.S. Regular Army but are fewer than for Union volunteers. Manuscript records, therefore, often become indispensable. Even these, for a few units, are lacking, and gaps in records of other organizations, where some unit histories do exist, are by no means rare. The most important source for information on which a Confederate unit history can be based is the Compiled Military Service Records, which for Confederate units are all reproduced on microfilm. This microfilm can be examined at the National Archives in Washington. State archives and some other institutions will occasionally have copies of this film available, usually only for the state in which the institution is located. Now and then an anomaly will occur. For example, the Virginia and Maryland Compiled Military Service Records will also be found in the National Archives- Mid Atlantic Region in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. But other National Archives regional archives have unexpected records. The Southeast Region in East Point, Georgia, has some microfilm rolls for Kentucky; the Southwest Region in Fort Worth, Texas, has microfilm rolls on Arkansas; and the Rocky Mountain Region in Denver, Colorado, has some rolls for Tennessee. Each roll of the microfilm can be separately purchased.

The Confederate Compiled Service Records (CSRs) for each organization are arranged alphabetically by the name of the soldier. Since the organization is primarily by regiment, members of individual companies are interspersed in the files. The individual service records for each organization are preceded by the "Record of Events" or "Caption Cards" for that outfit. These same records, without the individual soldiers' records, are separately reproduced on National Archives microfilm publication M861, Compiled Records Showing Service of Military Units in Confederate Organizations, mentioned above.

The Confederate CSRs are generally superior as a source to the original muster rolls, with which they are frequently confused. This superiority is due to the fact that, in addition to the information on individuals found on the rolls and on the "Record of Events," the CSRs include original documents, especially for officers, some of which are priceless as historical sources and not found anywhere else. These CSRs also include transcriptions from Union prisoner-of-war and hospital records as well as transcriptions from Confederate medical registers and other sources. The fragile original rolls are generally useful only in certain statistical compilations and for the brief inspection comments for the categories of discipline, instruction, military appearance, arms, accoutrements, and clothing. When filled in at all, inspectors customarily wrote a single word for each heading, such as "good," "poor," or "excellent."

A second basic source for a Confederate unit history is the inspection reports reproduced on National Archives Microfilm Publication M935, Inspection Reports and Related Records Received by the Inspection Branch in the Confederate Adjutant and Inspector General's Office. The advantage of these records is that they generally provide a myriad of details on subjects of interest, such as the type of arms carried, statistics of men present and absent, military bearing and appearance, religious instruction, etc. Of special note is the concluding "Remarks" space, often filled by trenchant, unbiased analysis of the units' strengths and weaknesses. The drawbacks to these inspection reports are that they cover only the period 1864–1865 and that their method of indexing can be difficult to grasp.

Bound Confederate regimental records are drastically fewer in number than those for their opponents. They number only 109 volumes. Moreover, they are often records of accounts for clothing or arms and equipment rather than the letter books, order books, and descriptive books so plentiful for Northern troops. Unlike the Union records, in which most descriptive books were "carded," almost none of the bound Confederate unit books were "carded." Therefore little of the information appears in the CSRs. There is a certain appeal in these volumes as artifacts as well. They bear evidence of having been carried on many a weary march and penned over many a smokey campfire. Marginalia often appears in them. One scribe of Co. C, Fourth Kentucky Infantry, of the Orphan Brigade, noted his thoughts in the back of his clothing account book each Christmas:

Dec. 25th 1861. The birth day of Christ our redeemer finds our country struggling in the holy cause of liberty with the vile horde of robbers & assassins sent to burn and destroy by their master Abraham Lincoln who occupies the chair at Washington, D.C.December 25th 1862. Another Christmas has come and still we are engaged in the Bloody struggle to be free for more than two years we have been combatting with the vandal horde. To Day our army is stronger and more thoroughly Equipped Than Ever before.

Dec. 25th 1863. Yes, old Brick, and another Christmas has come and gone, and we are still combatting with the vandal horde; Are likely to be doing that same this time next Christmas. What a pity.

This account largely exhausts series of Confederate records in the National Archives arranged or indexed by unit. Beyond these, however, much can be painstakingly extracted by name searches of large series covering all of the Confederacy. The most significant names, such as those of colonels, lieutenant colonels, and majors, are likely keys to useful material in the letters received by the Confederate secretary of war and adjutant and inspector general, but any member of a unit may turn up in these series. The Unfiled Slips and Papers are a series in which all manner of fascinating material may appear, and frequently does, but it will be found only by the intrepid and the patient.

State archives often have records useful for both Confederate and Union unit histories. Brief overviews of their holdings are in A Guide to Archives and Manuscripts in the United States (1961), edited by Philip M. Hamer, and partially updated in Directory of Archives and Manuscript Repositories in the United States (1988), issued by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission. Although state archives are not the focus of the present work, the following entry from a draft "Inventory to Civil War Records in the New York State Archives" of May 1987, still unpublished, suggests the usefulness of state resources:

Historical Notes on New York State Volunteer Regiments, 1861–1865. 7 volumes.This series describes the organizational history of New York State Volunteer infantry, artillery, and cavalry regiments that participated in the Civil War. These "historical notes" were compiled by the bureau most likely between 1863 and 1866. Each regimental history consists of twenty pages which provides information on the unit's recruitment and organization; terms of enlistment; bounties paid; presentation and final disposition of flags; arms, uniforms, and equipment; and mustering out. Unfortunately, the quantity and quality of the information varies widely. Some unit histories are extremely complete and detailed while others contain no information whatsoever. Although much of the information contained in this series can be obtained from Frederick Phisterer's New York in the War of the Rebellion (Albany: J. B. Lyon Company, 1912), there are some topics on which Phisterer does not touch. These include arms and equipment issued and used by regiments, bounties paid, and aid furnished by federal, state, or local authorities. The series is arranged by branch of service (infantry, artillery, and cavalry) and therein by unit number.

The staff of the archives in Albany stresses that in many ways this series is inferior to Phisterer's compilation for general regimental history. It may, however, from time to time supply some key information not found elsewhere. The Virginia State Archives includes miscellaneous records by unit among the records of its Adjutant General's Office and additionally has unit rosters compiled many years after the war. Pension records for Confederate soldiers, as noted earlier, are in the archives of the states in which the individual pensioners resided. Such pensions are not generally arranged or indexed by unit.

Commands higher than the regiment can be the means of tapping a rich vein of regimental documentation. Brigades composed of several regiments were sometimes the subject of their own histories. The story of the Fourth Georgia Infantry, for example, is interwoven with the History of the Doles-Cook Brigade, Army of Northern Virginia . . . (1903; reprinted 1981), by Henry W. Thomas, and the Sixth Wisconsin Infantry plays a significant role in The Iron Brigade, A Military History (1961), by Alan T. Nolan. Division histories are few, and corps histories are on a level so elevated as to relegate regiments to insignificance, though the corps histories should convey a sense of the corps's fundamental place in a soldier's self-image.

Confederate brigade, division, corps, and army records can be located through pages 259–301 of Henry P. Beers's The Confederacy: A Guide to the Archives of the Government of the Confederate States of America (1968; reprinted 1986), but you must first learn from other sources, such as the tables of organization in the Official Records, which regiments were part of these commands. Two brigades are particularly well documented at the National Archives: Gen. John C. Breckinridge's First Kentucky (or Orphan) Brigade (Beers, pp. 287–288), and Henry A. Wise's Virginia Brigade (Beers, p. 336). At the department level, records created and maintained by the Department of Richmond (Beers, pp. 281–282) and East Tennessee and West Virginia (Beers, pp. 265–267) merit mention as notably rich, although finding regimental references in them would be exceedingly time-consuming.

In the U.S. Army, higher command records are in Record Group 393, Records of U.S. Army Continental Commands (formerly part of RG 98, and so identified in Munden and Beers's Guide to Federal Archives). Dyer's Compendium is a good and handy guide to which such commands each Federal regiment belonged as well as a convenient source for command composition and names of commanders. Record Group 393 is distinctive among Civil War record groups in having a five-volume inventory, and it is important to know which inventory volume number you are referring to. Volume 2 in the inventory has records of corps, divisions, and brigades and is the one to use for seeking elusive regimental documents. The relevant records can be traced by looking at the index in the back of the inventory and proceeding from higher to lower command levels. The other inventory volumes for Record Group 393 are much less likely to prove useful for regimental history but are worth at least a cursory examination.

A survey of records of commands above the regimental level would be incomplete without mention of returns for those commands. Although much of the primarily statistical data found on those oversized sheets appears in the Official Records, not all of it does, and from time to time they will furnish answers to questions not found elsewhere. The returns are of prime interest, of course, to those studying numbers of men present and absent on particular occasions. For the Confederates, they will be found in RG 109, entry 65, under "Post, Department, and Army Returns, Rosters, and Lists. 1861–1865," and for the Federals, in Record Group 94, entry 66, "Returns of Military Organizations. Early 1800's–Dec. 1916." The "Record of Events" section on Union returns for army corps, departments, and posts was "carded," and is now entry 65 of Record Group 94. The "carding" in this case was especially beneficial, since the returns themselves are even more fragile than muster rolls and have also often been repaired by opaque War Department tape.

Another source to remember in collecting regimental sources in the National Archives and elsewhere is documentation both public and private on individuals who eventually rose to brigade command and beyond. Confederate general officers have a separate series in which their service records appear as well as CSRs in their original regiments. This separate series is reproduced on National Archives Microfilm Publication M331, Compiled Service Records of Confederate Generals and Staff Officers and Nonregimental Enlisted Men. The historian of the Twenty-first Illinois Infantry who fails to pay attention to the numerous sources on that outfit's first colonel does so at his peril. The colonel's name was Ulysses S. Grant.

Two enlisted men in the title story of Crane's collection expressed well the importance a unit—and by extension its records—held for their generation:

They could prove that their division was the best in the corps, and that their brigade was the best in the division. And their regiment—it was plain that no fortune of life was equal to the chance which caused a man to be born, so to speak, into this command, the keystone of the defending arch.

A Curse Before Parting

Because the records in the National Archives have not been edited or amended, they may contain documents that are harsh, irritating, or blatantly offensive. Perhaps because of this, they possess an immediacy lacking in more polished and palatable sources.

Scrawled boldly in pencil on the last page of the wallpaper-bound clothing account book of Company K of the Consolidated Confederate Second and Sixth Missouri Infantry is the following final shot before the regiment was paroled at the end of the war:

NoticeCompliments to the Yanks. May they suffer as these Patriots have for clothing & provisions. May their houses be burned as ours have been. May their mothers mourn for fallen children as the Confederate mothers have. May their sisters be treated by the victorious French as ours have been by the victorious Negro & Yankee, and may they finally be happy in seeing their wives ravished by the beloved Negro as some of ours have been by the soldiers of the "best government the sun ever shown upon."

Missouri Rebel

Meridian [MS]

May 11 1865

(RG 109, Chapter VIII, Vol. 91, part 1)

Michael P. Musick parlayed a childhood fascination with the Civil War into a rewarding career. A former student of Bell I. Wiley at Emory University, he has worked at the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, DC, since 1969. Mr. Musick was an adviser to Ken Burns's PBS series The Civil War and is the author of 6th Virginia Cavalry (1990), a regimental history and annotated roster, among other publications.

The author would like to thank Maryellen Trautman, National Archives Library, and Dr. Richard J. Sommers, U.S. Military History Institute, Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, for supplying valuable information and invaluable criticism for this piece.

Appendices:

- Appendix A: Checklist for Sources on Regimental History in the National Archives

- Appendix B: Colonel Cahill's Ninth Connecticut: One Regiment's Records

- Appendix C: Confederate Army Regimental Books

- Appendix D: Confederates from California

- Appendix E: Civil War Union Volunteer Regimental Books

Notes

1. Regulations for the Army of the Confederate States, 1862 (1861), para. 80 (pp. 8–9) and 120 (p. 12); Revised Regulations for the Army of the United States, 1861 (1862), para. 88 (p. 20) and 127 (p. 24), and other editions.

2. Stephen Z. Starr, a mid-twentieth-century scholar who pored through National Archives records to write a modern history of the Seventh Kansas Cavalry, discusses these records in an article, "The Second Michigan Volunteer Cavalry: Another View," Michigan History 60 (Summer 1976).