By George, IT IS Washington’s Birthday!

Winter 2004, Vol. 36, No. 4

By C. L. Arbelbide

As a student at Washington Elementary School in Kingsburg, California, I took great pride in enjoying the federal holiday dedicated to the "Father of Our Country," George Washington. Federal offices, banks, schools, and most business closed to pay him homage. That the February 22 holiday could have occurred in the midst of potential foul weather did not deter children across the land from enjoying a winter's holiday of play.

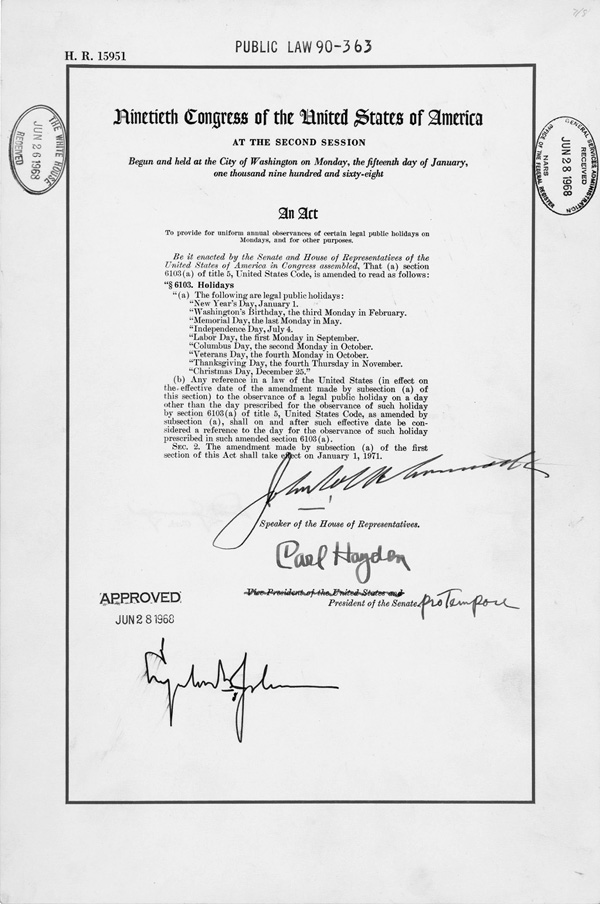

Before 1971, Washington's Birthday was one of nine federal holidays celebrated on specific dates, which—year after year—fell on different days of the week (the exception being Labor Day—the original Monday holiday). Then came the tinkering of the Ninetieth Congress in 1968. Determined to create a uniform system of federal Monday holidays, Congress voted to shift three existing holidays to Mondays and expanded the number further by creating one new Monday holiday.

Washington's Birthday was uprooted from its fixed February 22 date and transplanted to the third Monday in February, followed by Memorial Day being relocated from the last day in May to the last Monday in May. One newly created holiday—Columbus Day—was positioned on the second Monday in October, as Veterans Day—ousted from its November 11 foxhole—was reassigned to the fourth Monday in October (although rebellion by veterans' organizations and state governments forced the 1980 return of Veterans Day to its historic Armistice date of November 11).

That Washington's birth date—February 22—would never fall on the third Monday in February was considered of minimum importance. After all, who could ever forget all that George Washington meant to this country?

The Original "American Idol"

Historic dates, like stepping stones, create a footpath through our heritage. Experienced by one generation and recalled by those to come, it is through these annual recollections that our heritage is honored. In 1879 the Forty-fifth Congress deemed George Washington's birth date, February 22, a historic date worthy of holiday recognition.

Washington was a man of his time: a farmer, a soldier, and an owner of slaves. Named commander-in-chief of the American Continental army, he led the colonies to victory over England, securing independence for an infant nation. His political leadership led to his election as president of the 1787 Constitutional Convention. Once the states ratified the Constitution, he was elected the first President of the United States, completing two terms.

Everything about George Washington was entwined with the evolution of a young nation. His name was associated with virtue, honesty, strength, courage, and patriarchal leadership. Schools, bridges, towns, the national capital, and even a state were named in his honor.

His likeness graced currency, stamps, sculptures, and paintings. Manufacturers deemed his image as public property. Historian William Ayres has stated that Washington must "surely hold the record for the number of times the image of a historical figure appeared on goods made for the American home."

At six-feet, two and a half inches tall, Washington's presence enhanced his political stature. Succeeding generations found significant ways to periodically resurrect his memory, including the centennial birthday celebration of 1832 and the laying of the Washington Monument's cornerstone sixteen years later (1848). Close on the heels of the national centennial celebration of 1876, a patriotic colonial revival followed and, before the end of the century, a centennial observance of his death in 1899. With the 1930s carving of his likeness in stone on Mount Rushmore and the posthumous promotion to the rank of six-star General of the Armies in 1976, the numerous tributes continued to reaffirm George Washington's place as the original "American Idol."

In 1879—An Unprecedented Idea

In the late 1870s, Senator Steven Wallace Dorsey (R-Arkansas) proposed the unprecedented idea of adding "citizen" Washington's birth date, February 22, to the four existing bank holidays previously approved in 1870.

Originally federal worker absenteeism had forced Congress to take a cue from surrounding states and formally declare New Year's Day, Independence Day, Thanksgiving, and Christmas Day as federal holidays in the District of Columbia.

The idea of adding Washington's Birthday to the federal holiday list simply made official an unofficial celebration in existence long before Washington's death. A popular proposal, the holiday bill required little debate. Signed into law January 31, 1879, by President Rutherford B. Hayes, the law was implemented in 1880 and applied only to District federal workers. In 1885 the holiday was extended to federal workers in the thirty-eight states.

Washington's Birthday had become the first federal holiday to single out an individual's birth date. The honor lasted for less than a century.

Just Who Would Benefit?

While the urgency to revamp the federal holiday system in 1968 was spurred by the belief (although no statistics were available) that government employee holiday absenteeism would be kept to a minimum, other motivations began to take center stage.

On May 6, 1968, the Congressional Record noted a three-point benefit package directed specifically at families:

- "Three-day holidays offer greater opportunities for families—especially those whose members may be widely separated—to get together. . . ."

- "The three-day span of leisure time . . . would allow our citizens greater participation in their hobbies as well as in educational and cultural activities."

- "Monday holidays would improve commercial and industrial production by minimizing midweek holiday interruptions of production schedules and reducing employee absenteeism before and after midweek holidays."

Endorsing the proposed holiday changes were various business-related organizations including the Chamber of Commerce of the United States, the National Association of Manufacturers, the National Association of Travel Organizations, and the National Retail Federation.

The task of shepherding the holiday bill through the House Judiciary Committee fell to Representative Robert McClory, a Republican from Illinois. Noting "the bill has many purposes," McClory commented, "I would say the primary purpose, as far as I am concerned, is this: It will provide more opportunities for family togetherness and more opportunities for people to visit the great historic sites of our Nation, such as the great Lincoln country of Illinois, Williamsburg, Yorktown, Washington, D.C., Mount Vernon, Gettysburg, and a number of other historic places which we associate with these great national holidays." (How families from the West Coast were to do this in three days was not discussed.) McClory continued, "So the beneficiaries are going to be the men, women and children of the United States."

Just which "families" would reap the federal holiday benefits concerned Representative Harold Gross (R-Iowa). "I have an idea if we make Monday holidays, to fulfill the promise to merchants that they are going to do a better business, that employees of the stores of this country will have no holidays. They will work at selling merchandise. That is about what will happen."

McClory countered, "Let me say generally that the labor unions are in support of this legislation."

Gross replied, "I am not impressed by that."

McClory responded, "We have labor and management joined together in support of this legislation, which is a unique situation. Furthermore, I am not disappointed that someone will obtain an economic advantage from this legislation, because our whole society is built upon a strong economy. This bill will help promote that economy. That is reason to support this bill not a reason to reject it."

Point to Gross. He had successfully uncovered the bill's true purpose only to have the message lost in the avalanche of publicity being generated by business organizations in support of the legislation. A portion of America's nongovernmental workforce were about to lose their holiday rights in exchange for the business of America.

Well, Not All the Federal Holidays

Of the federal holidays, two were almost immediately exempt from the shift to Mondays: New Year's Day, January 1, and Christmas Day, December 25. The Wall Street Journal noted on March 27, 1968, that "Unlike some earlier versions of the Monday holiday bill, Rep. McClory's measure would leave July 4th untouched as Independence Day, and Thanksgiving would continue to fall on the fourth Thursday in November. Patriotic groups [had] been especially hostile to tampering with the Fourth of July, and some merchants were worried that a Monday Thanksgiving would disrupt existing retailing patterns."

That left Washington's Birthday, Memorial Day, and Veterans Day as the prime targets. The usual display of statistics, charts, and graphs highlighting non-Monday holiday traffic accidents and deaths were trotted out, as were pro and con public polls.

Although storm clouds were gathering around the idea of shifting Veterans Day from one month to another, it was the proposal to shift the Washington's Birthday federal holiday from February 22 to the third Monday in February that caused both a congressional and public outcry. That Washington's identity would be lost forced McClory to insist, "We are not changing George Washington's birthday" and further note, "We would make George Washington's Birthday more meaningful to many more people by having it observed on a Monday."

The Rename Game

Opponents were not convinced. It had been McClory—a representative from "the land of Lincoln"—who had attempted in committee to rename "Washington's Birthday" as "President's Day." The bill stalled. The Wall Street Journal reported on March 27: "To win more support, Mr. McClory and his allies dropped the earlier goal of renaming Washington's Birthday [as] Presidents' Day, [which] mollified some Virginia lawmakers. He also agreed to sweeten the package by including Columbus Day as a Federal holiday, a goal sought for years by Italian-American groups."

"It was the collective judgment of the Committee on the Judiciary," stated Mr. William Moore McCulloch (R-Ohio) "that this [naming the day "President's Day"] would be unwise. Certainly, not all Presidents are held in the same high esteem as the Father of our Country. There are many who are not inclined to pay their respects to certain Presidents. Moreover, it is probable that the members of one political party would not relish honoring a President from the other political party whether he was in office, no matter how outstanding history may find his leadership."

Why the "Third" Monday in February?

Had the name of the holiday been changed to Presidents' Day, McClory would have gained instant federal holiday recognition for Illinois native son Abraham Lincoln. With the name change no longer a possibility, McClory positioned the federal holiday on the third Monday in February—a date closer to Lincoln's February 12 birth date, knowing the dual presidential birthday spotlight could be shared by Lincoln.

McClory went so far as to suggest a direct link between the February 22 birth date and the third Monday existed: "Indeed, his [Washington's] birthday will be celebrated frequently on February 22, which in many cases will be the third Monday in February. It will also be celebrated on February 23, just as it is at the present time when February 22 falls on the Sunday preceding."

Virginia representatives Richard Harding Poff and William Lloyd Scott—believing that removing the direct date removed the heritage the date represented—countered the inaccurate information. Poff declared, "Now what that really means is never again will the birthday of the Father of our Country be observed on February 22 because the third Monday will always fall between the 15th of February and the 21st of February." Poff proposed an amendment to retain the February 22 date.

Scott added, "I submit that if we pass this bill without the amendment that Mr. Poff has offered, we are going to run into just as much of a hornet's nest as the one during President [Franklin D.] Roosevelt's regime when he changed the date of the observance of Thanksgiving."

Knowing that future generations were caretakers of the past, Dan Heflin Kuykendall (R-Tennessee) cut to the heart of the matter. "If we do this, 10 years from now our schoolchildren will not know or care when George Washington was born. They will know that in the middle of February they will have a 3-day weekend for some reason. This will come."

The question was taken, and on a division (demanded by Poff) "there were [verbal] ayes, 50, noes 49." McClory demanded tellers to count the votes. "The Committee again divided, and the tellers reported there were 'ayes 59, noes 67.'" With more than 50 percent opposed, the amendment was rejected.

Perpetual Calendar, Anyone?

Had activism followed Poff's failed amendment, creative compromise would still have been possible. Supporters could have seized the moment—capitalizing on McClory's voiced belief that February 22 would fall on a Monday. A check with the crystal ball of calendars—the perpetual calendar—would have confirmed Poff's assertion that February 22 would never fall on the third Monday in February and would have revealed that February 22 would occasionally fall on the fourth Monday in February. Never proposed as an alternative amendment, the "fourth Monday" opportunity passed silently by.

The Erosion of America's Memory

With the traditional ten-day buffer between Lincoln's February 12 and Washington's February 22 birthdays eliminated, the erosion of America's memory began. That Lincoln's birthday had never achieved federal holiday status was about to change.

When the new federal law was implemented in 1971, only two days separated Abraham Lincoln's Friday birthday of February 12 from the Washington's Birthday holiday that fell on February 15—the third Monday in February. Ironically, Washington's birth date of February 22 fell one week later on the fourth Monday in February.

From year to year the calendar compressed and expanded the number of days between the two birthday observances from as few as two days to as many as eight.

Then there was the response by state governments. While Congress could create a uniform federal holiday law, there would not be a uniform holiday title agreement among the states. While a majority of states with individual holidays honoring Washington and Lincoln shifted their state recognition date of Washington's Birthday to correspond to the third Monday in February, a few states chose not to retain the federal holiday title, including Texas, which by 1971 renamed their state holiday "President's Day."

Crossing state borders on Washington's Birthday could lead to holiday title confusion. Then came the power of advertising.

A Golden "Promotional" Egg

For advertisers, the Monday holiday change was the goose that laid the golden "promotional" egg. Using Labor Day marketing as a guide, three-day weekend sales were expanded to include the new Monday holidays. Once the "Uniform Monday Holiday Law" was implemented, it took just under a decade to build a head of national promotional sales steam.

Local advertisers morphed both "Abraham Lincoln's Birthday" and "George Washington's Birthday" into the sales sound bite "President's Day," expanding the traditional three-day sales to begin before Lincoln's birth date and end after Washington's February 22 birth. In some instances, advertisers promoted the sales campaign through the entire month of February. To the unsuspecting public, the term linking both presidential birthdays seemed to explain the repositioning of the holiday between two high-profile presidential birthdays.

After a decade of local sporadic use, the catchall phrase took a national turn. By the mid-1980s, the term was appearing in a few Washington Post holiday advertisements and an occasional newspaper editorial. Three "spellings" of the advertising holiday ensued—one without an apostrophe and two promoting a floating apostrophe. The Associated Press stylebook placed the apostrophe between the "t" and "s" ("President's Day"), while grammatical purists positioned the apostrophe after the "s" believing Presidents' deferred the day to the "many" rather than one singular "President. "

Advertising had its effects on various calendar manufacturers who, determining their own spelling, began substituting Presidents' Day for the real thing. Eventually, when printed in the newspaper or seen on the calendar, few gave thought to its accuracy.

Meanwhile, Back at the Schools

In 1968, no educational organizations—teachers, administrators, or PTAs—were listed as supporters of the holiday bill. While Congress counted on state legislatures to align their state holidays with those of the federal government, no thought was given to the effect revised federal holidays would have on individual school districts.

Many school districts could independently determine their calendar until state legislatures began requiring of school districts a set number of days within a school year. Although school districts made every effort to honor federal holidays, administrators were faced with juggling an already packed school year calendar.

Where once school ended at the end of May and began after Labor Day, school years have expanded into June and even August as educators found it necessary to lengthen the school year to accommodate the evolving required educational mandates. Rather than continue to erase the summer break, schools began omitting various federal holidays (most often Columbus Day, Veterans Day, and the generic "Presidents' Day") from school calendars. Political correctness caused schools to shy away from ignoring the Martin Luther King, Jr., holiday, while the 'title confused' third Monday in February—now being passed over as a holiday—emerged with newfound purpose as staff development time, teacher/parent meetings, or as a backup snow make-up day.

Federal holidays whose authentic titles once automatically graced school calendars were removed for fear that parents and students would interpret their appearance as confirmation that students would have the day off.

For students in Texas, the renaming of the state's Washington holiday to "President's Day" established the beginning of generations of children whose connection to Washington was fading. California took the opposite tact, requiring schools to promote lessons about George Washington on the Friday before his Monday holiday.

Perhaps the ultimate ironic reaction occurred in George Washington's native home state of Virginia. Ignoring not only the correct federal title but Virginia's own state holiday title— "George Washington Day"—the state's Department of Education ousted the accurate "Washington's Birthday" holiday title from the 1998 Standards of Learning in favor of the advertising soundbite.

By the late 1990s, the snowball effect took hold. With more publishing houses substituting Presidents' Day for "Washington's Birthday," children's holiday books based on incorrect research were infiltrating their way into school and public libraries.

Schools in Washington's own birth county (Westmoreland County) and the City of Alexandria (near Mount Vernon and home to the long-running George Washington Birthday Parade) succumbed to the Presidents' Day phrase. At the beginning of the 2004–2005 school year, of Virginia's 134 school districts, only two received an "A" for accuracy. Both the Fairfax and Richmond County Public Schools systems listed the correct "Washington's Birthday" holiday title on their respective Internet sites.

A Phantom Presidential Proclamation

Ahhhh, the Internet. A haven for homemade home pages. As web writers began pointing fingers at who was responsible for the federal Washington's Birthday holiday title being changed to Presidents' Day, web sites unanimously attributed the change to a presidential proclamation—issued by President Richard Nixon—who was in office when the "Uniform Monday Holiday Law" was enacted in 1971.

Like a platter of hors d'oeuvres, word-for-word segments of the "alleged" proclamation were passed from one web site to another (including educational based and various U.S. embassy sites) as if cut and paste was the new style of web writing. Supposedly—it was surmised—Nixon had issued a presidential proclamation in 1971 changing the name from Washington's Birthday to Presidents' Day.

Had any writer cared to call the Nixon Presidential Materials Staff of the National Archives and Records Administration; the staff at the Nixon Library in Yorba Linda, California; or the law library at the Library of Congress, they would have learned that no such presidential proclamation exists. As an archivist at the Nixon staff commented, this phantom presidential proclamation was 'the ultimate in presidential urban myths."

In the absence of fact checking, web writers had relied on a fictitious source—an Internet story whose origins were traced to an Arkansas Democrat-Gazette humor column authored by Michael Storey.

A "Cat's" Tale

That President Bill Clinton really had issued a proclamation in 2000 declaring the third Monday in February to be Presidents' Day irked Storey, who responded with a fictional interview as to how Presidents' Day got its name. The source for the "interview" was the author's cat, who "asserted" that Nixon had created a presidential proclamation changing the federal holiday's name from "Washington's Birthday" to "President's Day. " Web writers ignored the author's "fictitious" disclaimer.

USA Today's Richard Benedetto quoted from the mythical story. "So how did Washington's Birthday morph into President's Day? It seems we have Richard Nixon to thank—or blame—for that. On February 21, 1971, Nixon issued a proclamation naming the holiday 'President's Day,' 'the first such three-day holiday set aside to honor all presidents, even myself.'"

In 2002, Ron Wolfe, also of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, recalled the aftermath. "Told that he [Benedetto] may have quoted a . . . cat to prove his point, Benedetto set the paper's library to work, trying to track down again where he found the quote. " Although no citation was found, no retraction appeared in USA Today.

What Nixon did in 1971 was to issue the traditional standard executive order announcing the implementation of new federal legislation. Nixon's executive order reminded citizens, as did many newspapers on January 1, of the new federal holiday calendar being implemented: New Year's Day, January 1; Washington's Birthday, the third Monday in February; Memorial Day, the last Monday in May; Independence Day, July 4; Labor Day, the first Monday in September; Columbus Day, the second Monday in October; Veterans Day, the fourth Monday in October, Thanksgiving Day, the fourth Thursday in November; and Christmas Day, December 25.

Nixon did—in a separate statement—recognize the birthday of Abraham Lincoln but did not suggest, refer to, or use the term "Presidents' Day" in either of the executive orders.

Coming Full Circle

Representative Gross's concern for the workers who might find themselves without holidays was justified. Manufacturers and business were not bound to federal holiday laws. Three-day holiday weekends were sales bonanzas. Workers who once enjoyed midweek holidays were finding little support from management to benefit from Monday holidays.

Where white-collar profession enjoyed the day off, blue-collar work forces could not. Workers in travel and tourism industries, home improvement centers, recreation-related business, as well as gas stations and the trash-collecting industry rarely have any holidays off.

The closest the country comes to a complete holiday shutdown is Christmas Day, a fixed date not restricted to a Monday holiday. In the name of uniformity, Congress succeeded in separating the public into two groups: those with and those without holidays.

Representative Kuykendall's prediction of schoolchildren not knowing or caring when George Washington was born has come to pass, too, even in Washington's home state of Virginia, where the state's Department of Education removed the first President's identity from the February holiday.

On the bright side, there is the federal Office of Personnel Management's holiday Internet site, which attempts to verify the correct federal holiday title, noting: "This holiday is designated as 'Washington's Birthday' in section 6103 (a) of title 5 of the United States Code, which is the law that specifies holidays for Federal employees. Though other institutions such as state and local governments and private business may use other names, it is our policy to always refer to holidays by the names designated in the law. "

At Mount Vernon the public relations department removed all references to the Nixon proclamation and Presidents' Day from their Internet site in December of 2003. Both Mount Vernon and the National Park Service's George Washington's Birthplace National Monument offer the most accurate look at the heritage associate with the Washington's Birthday holiday.

Out in Washington, Virginia, the Rappahannock County Library initiated, in February 2004, the art and essay program "By George, It's Washington's Birthday"TM to counter the advertising term and take back the rightful federal and state holiday heritage associated with Virginia's native son.

Ignore or Restore?

Only two Americans have been honored with individual federal holidays. The original intent was to recognize them on their birthdays. The Uniform Monday Holiday Law removed the February 22 connection to Washington. Years later, having learned their lesson, Congress made certain the Monday in January selected for the new holiday was the Monday on which King's birth date would occasionally fall. That one holiday has the direct birth date connection and the other does not still contributes to the confusion—is the third Monday in February Washington's Birthday or Presidents' Day?

Washington's birthday holiday came about seventy years after his death. The King holiday has emerged within the primary family's lifetime. As there are no primary survivors to speak for George Washington, it falls to Congress to resurrect the original honor accorded Washington by the Thirty-seventh Congress in 1879 and re-link the federal holiday to his birth date of February 22.

The question facing Congress is whether to restore the holiday to the February 22 birth date or shift the holiday to the fourth Monday in February, allowing February 22 to occasionally fall on that Monday.

Perhaps Congress can find the answer right in its own backyard—within the halls of the Capitol. Members can ponder the question while gazing at the Apotheosis of Washington mural adorning the U.S. Capitol Rotunda. Or contemplate how their annual congressional February ritual of reading Washington's "Farewell Address" came about. What reason did the citizens, in 1862, have in bringing petitions to Senator Andrew Johnson demanding the reading of the address on Washington's birthday? The country was in the midst of civil war. The citizens looked to Washington's words for strength, and Johnson carried the message: "I think the time has arrived when we should recur back to the days, the times, and the doings of Washington and the patriots of the Revolution, who founded the government under which we live." Is there ever a time in our country's present or future circumstances that we could not benefit from being reminded of how the citizens who came before dealt with the crises associated with being a country?

The recognition accorded the February 22 date is—in effect—a look back at how the country survived in spite of itself. It is also a time to reflect on the origins of slavery. Considering that February is also Black History Month, the existence of Washington's Birthday provides an opportunity to take an expanded look at the issue of civil rights from the country's earliest days—not just the days of the Civil War or the 1950s and 1960s.

Washington's deeds and words continue to inspire. Can we afford to ignore the contributions of George Washington, or shall we restore the connection to this special heritage and our unique historical past? It's something to contemplate on Washington's Birthday holiday in 2005, when it falls on February 21—the closest it can ever come to Washington's birth date of February 22. Federal holiday history continues to be a work in progress.

C. L. Arbelbide is a historian and storyteller specializing in federal holiday history and unique events associated with the White House, the U.S. Capitol, and the National Mall. She is the author of The White House Easter Egg Roll (1997).

Note on Sources

The Nixon Presidential Materials Staff of the National Archives and Records Administration is the custodian of the historical materials created and received by the White House during the administration of Richard Nixon, 1969–1974, and is located in College Park, Maryland.

The House debate on the Monday Holiday Bill is recorded in the Congressional Record, May 6 (pp. 11827–11830), 7 (pp. 12077–12079), and 9 (pp. 12583–12611), 1968.

Useful secondary sources are William S. Ayres, "At Home with George: Commercialization of the Washington Image, 1776–1876, " in George Washington: American Symbol (New York : Hudson Hills Press, 1999); and Stephen W. Stathis, "Federal Holidays: Evolution and Application" (January 21, 1999), Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress.

The controversy over moving the date of Thanksgiving is discussed in G. Wallace Chessman, "Thanksgiving: Another FDR Experiment, " Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives 22 (Fall 1990): 273–285.

President Nixon's mythical proclamation about "President's Day" is told in Michael Storey's column of "humor and/or total fabrication, " "Otus the Head Cat: Clinton joins disgraced Nixon in ride on George's coattails," Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, February 26, 2000, p. E3; and retold by Richard Benedetto, "Presidents Day? No president's day," USA Today, February 19, 2001, p. A7. Ron Wolf's correction, "We can tell no lie: Monday is not 'President's Day,'" appeared in the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, on February 17, 2002, p. 1A.

The web sites for Mount Vernon and George Washington's Birthplace National Monument are www.mountvernon.org and www.nps.gov/gewa/index.htm; the Rappahannock County Library web site is at www.rappahannocklibrary.org .

The nine federal holidays before 1971 were New Year's Day, January 1; Inauguration Day (every four years), January 20; Washington's Birthday, February 22; Memorial Day, May 31; Independence Day, July 4; Labor Day (the original Monday holiday), first Monday in September; Veterans Day, November 11; Thanksgiving Day, fourth Thursday in November; and Christmas Day, December 25.