Thief’s Sentencing Sends ‘Strong Message’

By Kerri Lawrence | National Archives News

WASHINGTON, May 2, 2018 — When a federal judge sentenced Antonin DeHays, it marked the end of a long and twisted tale involving the theft of hundreds of American artifacts. It also wrapped up an investigation that involved countless hours of sifting through records and examining evidence to bring that thief to justice.

The story began in November 2016, when a private researcher’s request to view items in Record Group 242 tipped off the National Archives and Records Administration staff in College Park, Maryland, that something may be amiss.

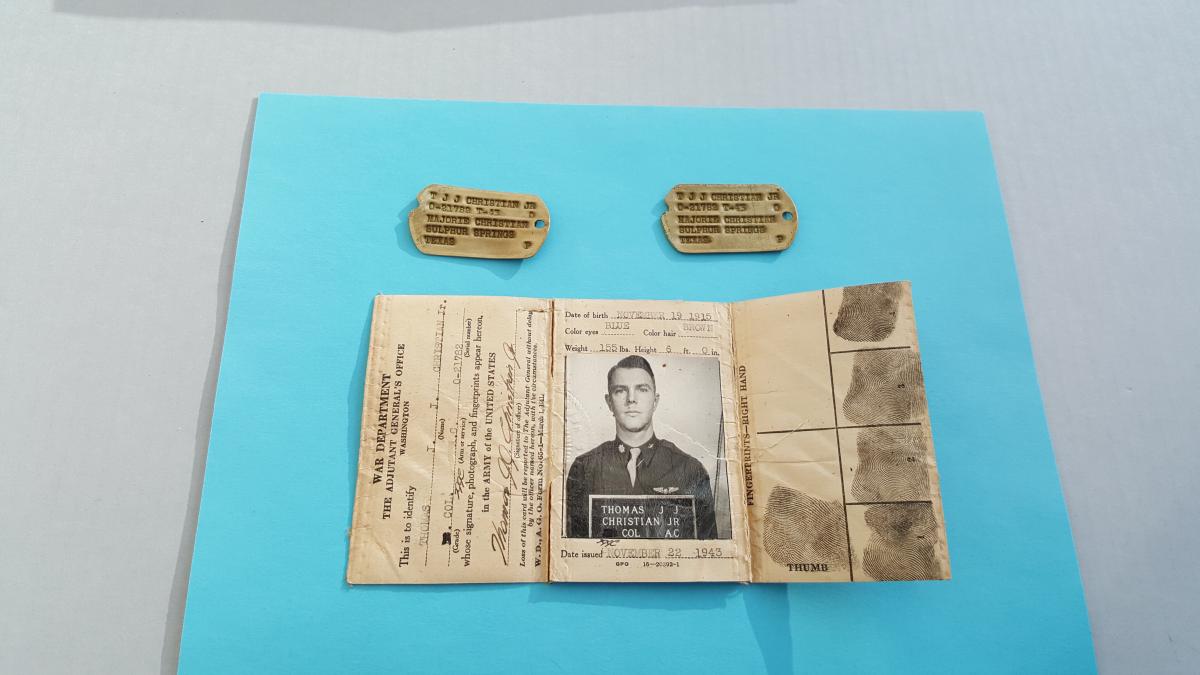

The researcher was searching specifically for a set of identification tags (also known as “dog tags”) belonging to a famed World War II aviator named Thomas Christian, a distant relative of Stonewall Jackson. When she could not locate the identification tags in the proper folder, the researcher alerted staff . . . and the scenario began to unfold.

Per protocol, reference staff double-checked the files themselves. When the identification tags still did not turn up, they notified the agency’s Holdings Protection and Recovery Staff, who informed investigators from the Office of Inspector General (OIG).

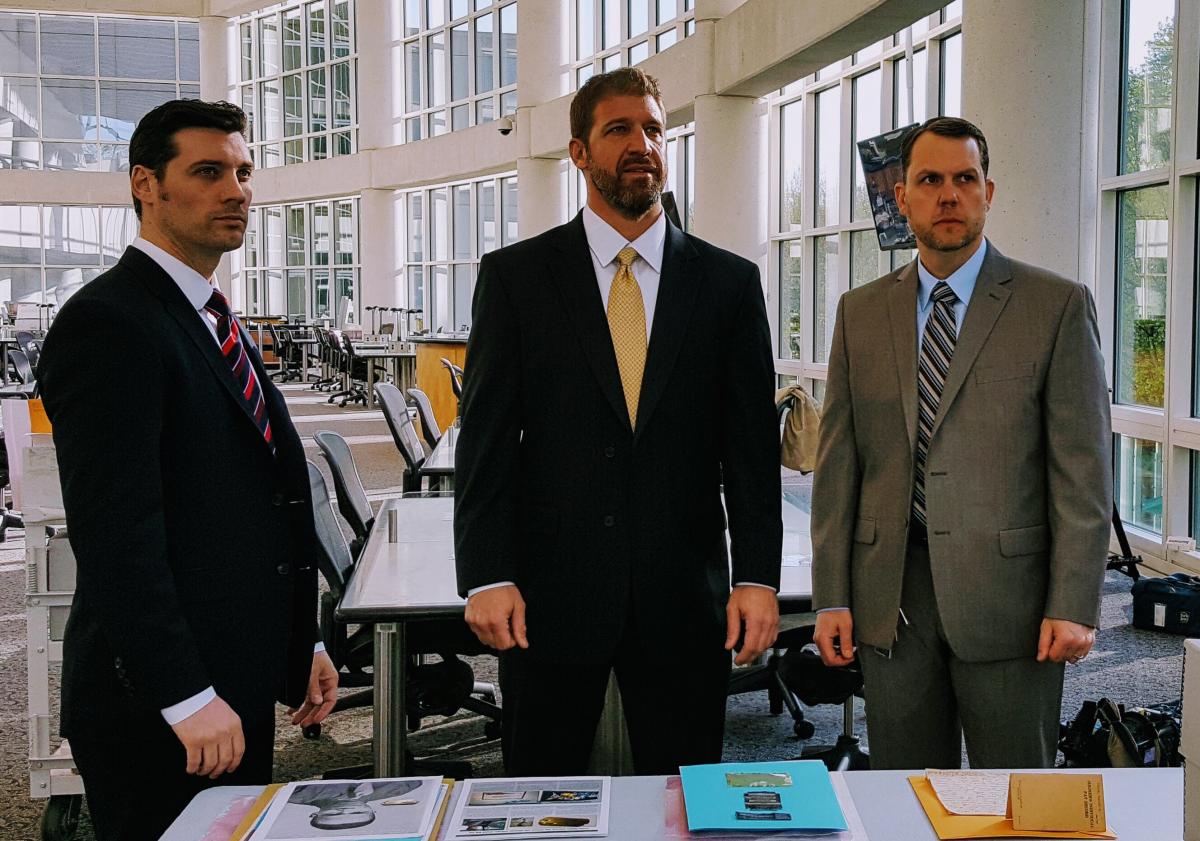

David Berry, an OIG special agent, led the investigation.

“Over the next several months, we continued getting follow-up notifications from the Holdings Protection and Recovery staff for this particular series of records that other items were possibly missing as well,” Berry said. Upon closer inspection, the missing items had a similar fact pattern, triggering an investigation.

“As we began taking a much closer look at what was missing, that’s when we really started believing something big was happening here,” Berry added.

Investigators immediately requested an inventory of everything within the series of records, explained Jason Metrick, Assistant Inspector General for Investigations.

“We asked that an inventory control system be implemented, item by item, for this entire series of records,” Metrick said. “That was no small feat, however, as there were about 30,000 airmen’s names associated with those files. The agency really stepped up and dedicated all the necessary resources to make that inventory happen quickly.”

Metrick emphasized the cooperation between the agency and the investigative team throughout the process, which he said he fully credits for the success of the investigation.

Berry explained that they narrowed down a list of suspects “based on what boxes the ID tags and records went missing from, who had requested these record boxes, and who had access to the missing records over time...and trends began to emerge.” He told of members of the investigative team and the agency having to search through hundreds of handwritten research requests, or “pull slips,” combing them for commonalities and clues.

Meanwhile, the agency began to put new protocols into place in coordination with investigators. The entire series was moved to an area with additional security measures, and special attention was given to any box that was served to researchers. Berry explained, “Private researcher Antonin DeHays, a World War II historian and recognized expert on the D-Day invasion, immediately jumped out as a person of interest.”

Once identified, special agents sought search and arrest warrants for DeHays, who was questioned and later arrested.

The investigation concluded that from 2012 to 2017, DeHays stole at least 291 U.S. service members’ identification tags and at least 134 other related items, including identification cards, personal letters, photographs, a Bible, and pieces of U.S. aircraft downed in Europe during the war.

Some of the identification tags bore evidence of damage, such as dents and charring due to fire sustained during crashes of Allied aircraft that were shot down or crash-landed within German-controlled areas of Europe during World War II.

DeHays kept some of the stolen tags and other stolen records for himself and gave others as gifts. He sold many of the items to unsuspecting buyers on eBay and elsewhere. Prior to selling the dog tags, DeHays sometimes removed markings from them that were made in pencil. Many of those pencil markings were believed to have been made by the German military after they had taken the tags from the deceased or captured American servicemen.

In the U.S. District Court in Greenbelt, Maryland, Judge Theodore D. Chuang sentenced DeHays to 364 days in prison; three years of probation, including eight months home confinement; 100 hours of community service; and restitution of $43,456.96 to those who unknowingly purchased the stolen goods.

Chuang said DeHays committed “an egregious, morally repugnant crime” of “the auctioning of our history and the personal effects of our war dead to the highest bidder.” The judge cited DeHays’ background as a historian as “an aggravating factor,” since he had first-hand knowledge of the significance of the records.

“He knows that the National Archives are an irreplaceable repository of our history that must be available not only to today’s scholars, but to our children who will someday seek to learn about their nation’s history,” Chuang said during sentencing.

“He knows that if others treated historical material as he did, he would have not have uncovered information he used in his own research,” Chuang added. “Particularly with his knowledge of World War II and the sacrifices made by both military and civilians in the European Theater, he cannot claim to be ignorant of how damaging this crime is.”

Judge Chuang directly addressed DeHays during the sentencing, stating “your actions were an affront to not only every American who has ever served in uniform under the flag that stands behind me...but to every American child...who has ever pledged allegiance to that flag in their classroom, because it is for them that the National Archives are preserved, so that they can be inspired by our high points and learn from our low points so as to make this nation and this work a better place in the future.”

Archivist of the United States David S. Ferriero said in a statement delivered during sentencing that by stealing World War II records from the National Archives and selling them to collectors, a thief victimized the American people and damaged the agency entrusted with safeguarding our nation’s records.

“Antonin DeHays’ selfish acts have robbed the public of a part of its collective history,” Ferriero said. “The materials stolen by Mr. DeHays are unique and irreplaceable, with a cultural, research and educational value that far outweighs any monetary value ascribed to them.”

“It is hard to fathom that anyone would steal records and artifacts documenting those captured or killed in the service of their nation,” Ferriero continued. “As a veteran, I am disgusted.”

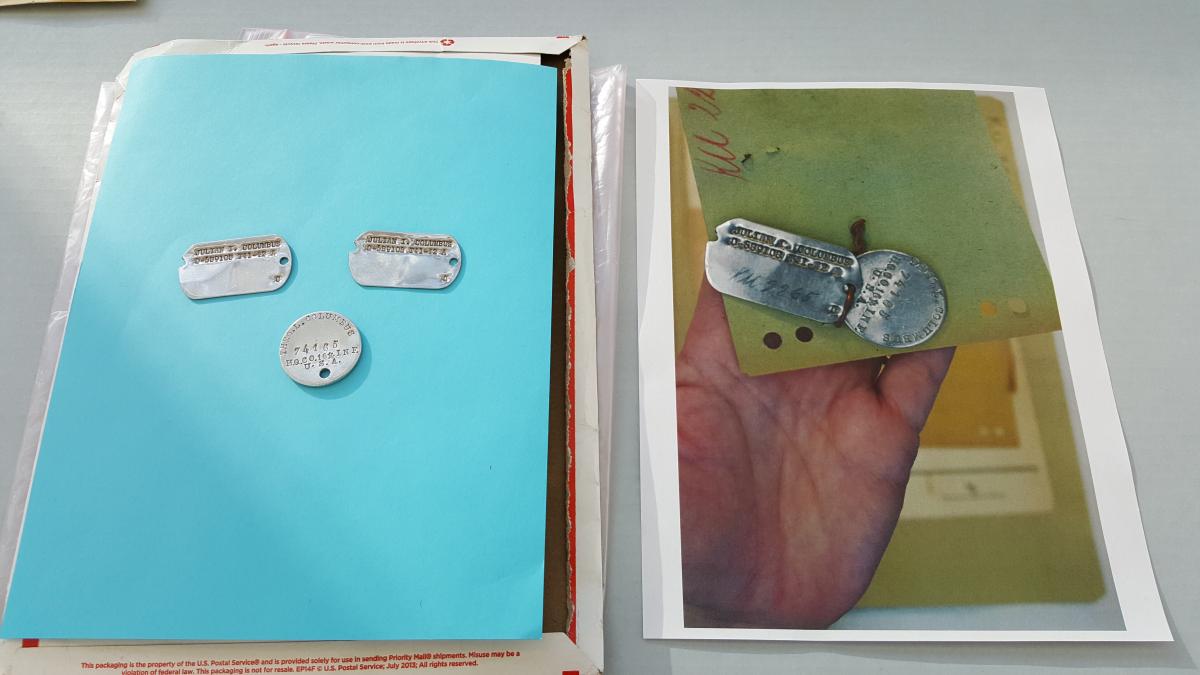

As a specific example, Ferriero spoke about “dog tags” worn by a U.S. serviceman killed in the line of duty during World War II. DeHays stole the two ID tags that were linked together with a wire loop. One of the tags was issued to 1st Lt. Julian Columbus, who died when his plane crashed on June 20, 1944, in Germany. The other had been issued to his father, who had served in World War I.

After stealing the tags, DeHays removed the wire loop, forever separating these items that had been linked together by a son in memory of his own father, who had passed away not long before he left to serve his country as his father had before him.

The National Archives was able to recover these tags. However, to date the investigation has been unable to recover the metal loop.

“DeHays appears to have disconnected them for his own personal, selfish gain, and in doing so, disrespected the memory of an otherwise inseparable bond of father and son,” Ferriero noted.

On another occasion, DeHays swiped two other dog tags that belonged to a Tuskegee Airman who died after his fighter plane crashed in Germany in September 1944. He traded one of the tags to a military aviation museum “in exchange for the opportunity to sit inside a Spitfire airplane,” according to court documents.

Ferriero explained that even when knowing what is missing, recovery can be difficult. Stolen records are often difficult to find, he said. Many similar items are legitimately for sale in the open market; so dealers don’t automatically suspect that they are stolen. Additionally once an item is sold, it may have been resold more than once. He explained that in some cases, there is no detailed record of the exact identity of a purchaser, and therefore it is difficult to follow that trail.

“We have about a 95 percent recovery rate on this case,” special agent Berry said, noting the many man-hours required to track down the missing records.

Ferriero added that he was pleased that the judge handed down a “stiff punishment” to DeHays for his crimes. “His sentence sends a strong message to others who may contemplate stealing our nation’s history. The theft of records from the National Archives amounts to stealing from the American people, and it merits a severe penalty whenever it occurs.”

Ferriero recognized the efforts of the National Archives’ Office of the Inspector General and the Justice Department to build a case and bring DeHays to justice. He also recognized the Holdings Protection and Recovery Staff within the agency for their continuing efforts to recover the stolen items.

The Archivist stressed that “the security of the holdings of the National Archives is my highest priority” and pledged to “continuously improve our policies and procedures to ensure our holdings are safe.”