Standout Census Stories: Schoel to Samuel to Saul Through Four Decades of Records

By Editorial Staff | National Archives News

WASHINGTON, February 10, 2022 — Editor’s note: The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) is scheduled to release the records of the 1950 Census on April 1, 2022. In anticipation, National Archives News is publishing a series of stories in the coming months about what can be gleaned from census records, and how personal histories can encapsulate entire eras. Our second Standout Census Story comes from Jenny McMillen Sweeney, archivist at the National Archives at Fort Worth.

Before becoming an Archivist in Fort Worth, I was an education specialist for the National Archives and Records Administration. I worked with students of all ages, helping them learn about the American government and our nation’s history through the agency’s rich holdings. I wish I had a dollar for every person who has told me that they think history is boring and there is no reason to study it, as I would probably be a pretty wealthy person by now.

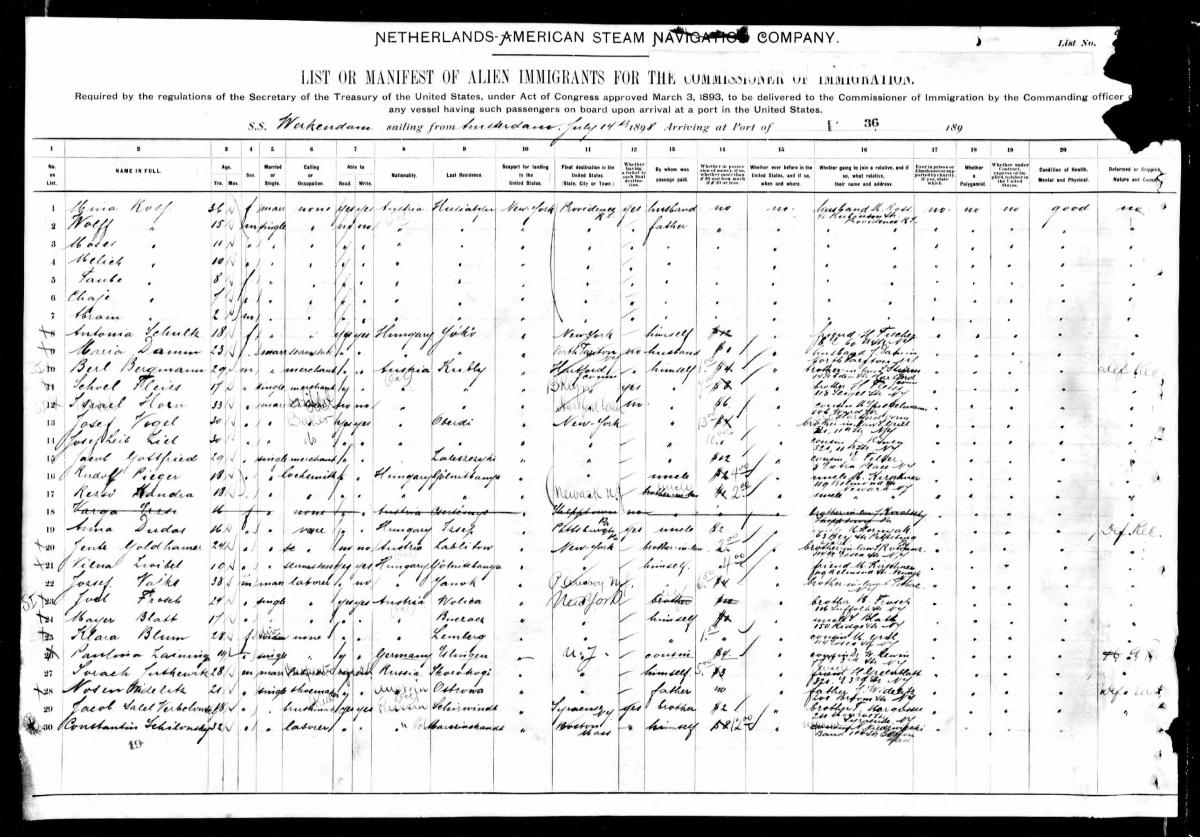

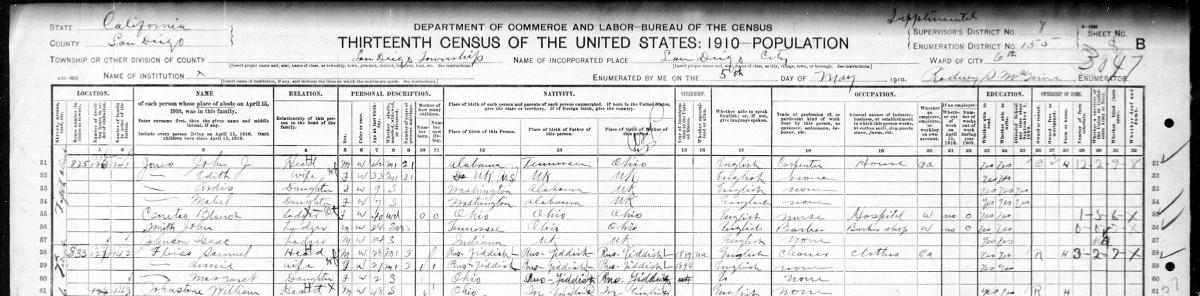

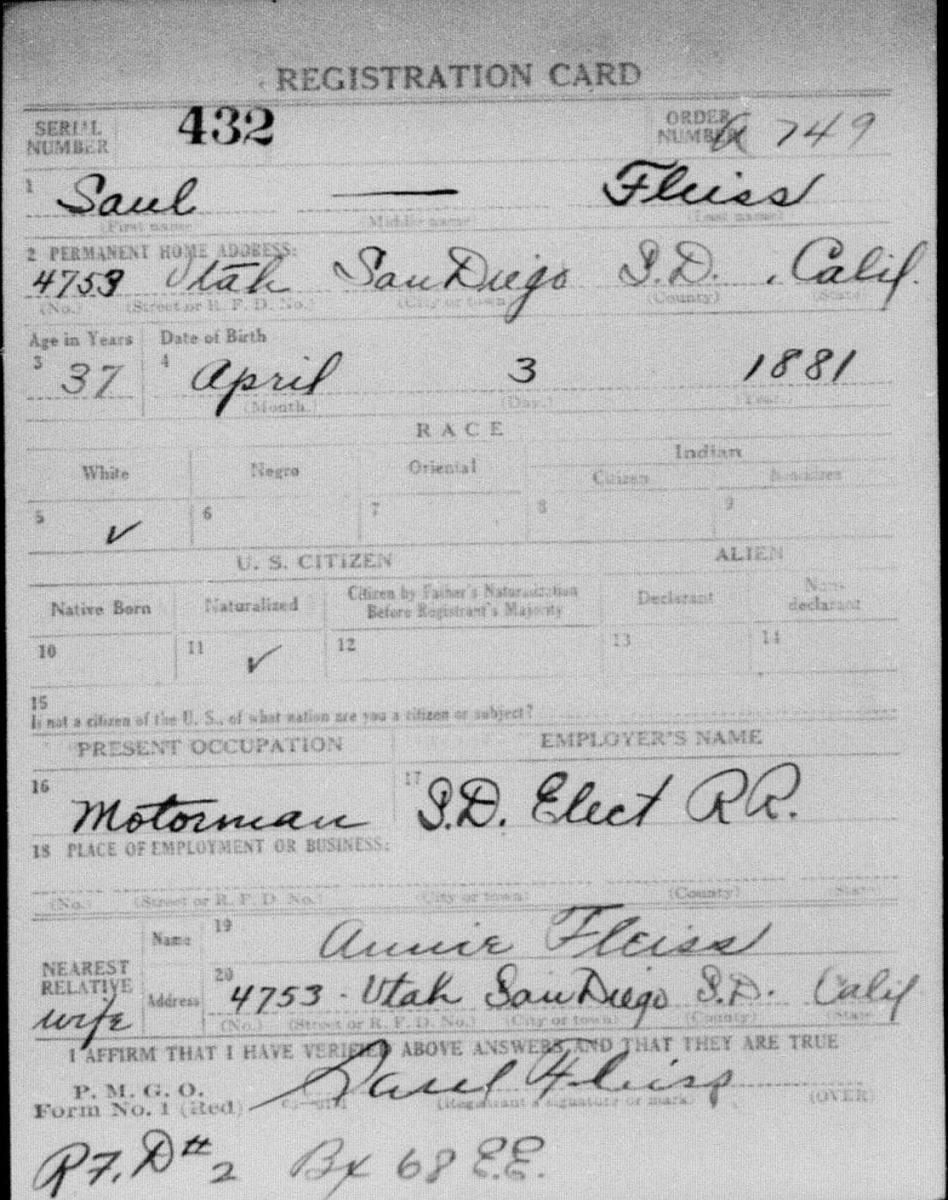

To combat this attitude, I created a fun activity many years ago, “One Man’s Journey,” which amazed students and adults. The activity followed one man’s life through numerous records, including a passenger arrival record, a draft registration card, and five census records. Working in groups, students answered a set of questions for each document or primary source. In the end, the group presented its own narrative of the individual’s life. To explore online activities using census records, visit DocsTeach.

The following is a brief overview of the records used in the activity. Saul Fleiss was the grandfather of now-retired Annie Davis, who was an education specialist at the National Archives at Boston and kindly provided family photos.

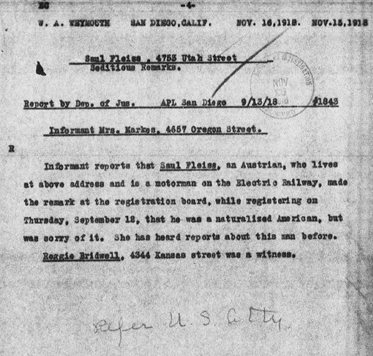

The narrative of Saul Fleiss’s life can be pieced together by the census records and other federal records found at the National Archives. However, some of the more intricate details of his life, such as why he moved from the east coast to the west coast or why he was so upset with having become a naturalized citizen, causing him to make seditious remarks while registering for the draft, are not revealed.

Because of the varied answers provided in the records, some students over the years have questioned if Saul was on the up-and-up or if he was trying to hide something.

What I would then explain to the students is that one must have an understanding of the historical context when a primary source or record is created in order to have a clearer understanding. I would also explain that by questioning the record and corroborating information, it allows one to verify information. We would then walk through some of their most perplexing questions.

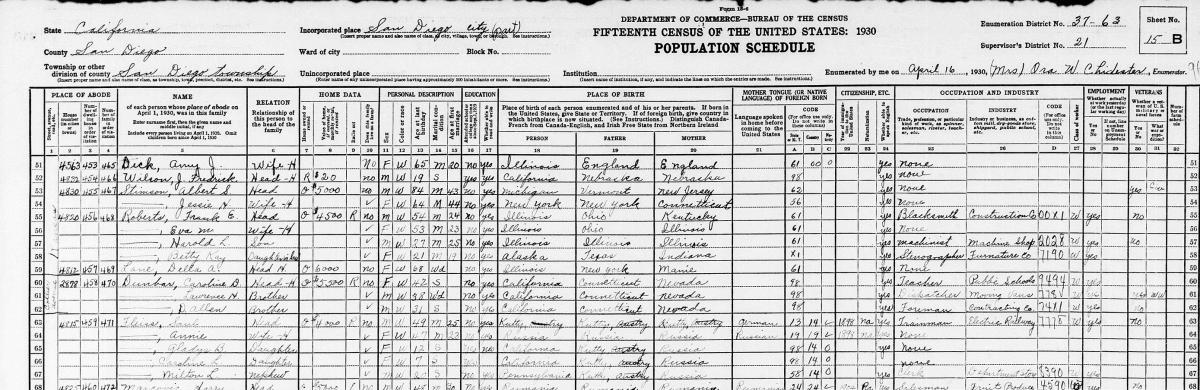

For instance, why did this individual’s name change multiple times from Schoel to Saul, Saul to Samuel, and back to Saul again? A reasonable guess is that Schoel was his Hebrew name and he chose to anglicize it once in America, and maybe Samuel seemed too formal so he just became Saul.

Why did Saul’s place of birth change on the different records over the years? At the time the records were created, the borders of what is current-day Ukraine were ever-changing, depending on the occupying country. Sometimes his place of birth was part of Poland, the Austro-Hungarian empire, or Russia. The census takers were instructed to record where the city was at the present day, not the country it was a part of at the time of the individual’s birth.

Why did the records list his native tongue differently over time? Being Jewish, his native language was more than likely Yiddish. However, it is a good bet that he also spoke at least some German, Polish, or Russian, if not fluently.

How were we able to learn that Saul’s social and economic status had changed over the years? When comparing the different records over time, it is possible to see how he was able to socially and economically climb the ladder. His salary increased, allowing him to purchase a home and have more disposable income to spend on things like a radio.

Once one knows to look beyond what is actually written in black and white, it is easier to gain a fuller and more complex understanding of an individual’s life and experiences. By truly looking at primary sources and asking questions about the times they were created, students are doing the work that historians do. This gives them skills that will come in handy in everyday life: learning to question information, why and how it was created, and if it is bonafide. From a personal standpoint, it was always so rewarding seeing students walk away from this activity realizing how cool history can be!